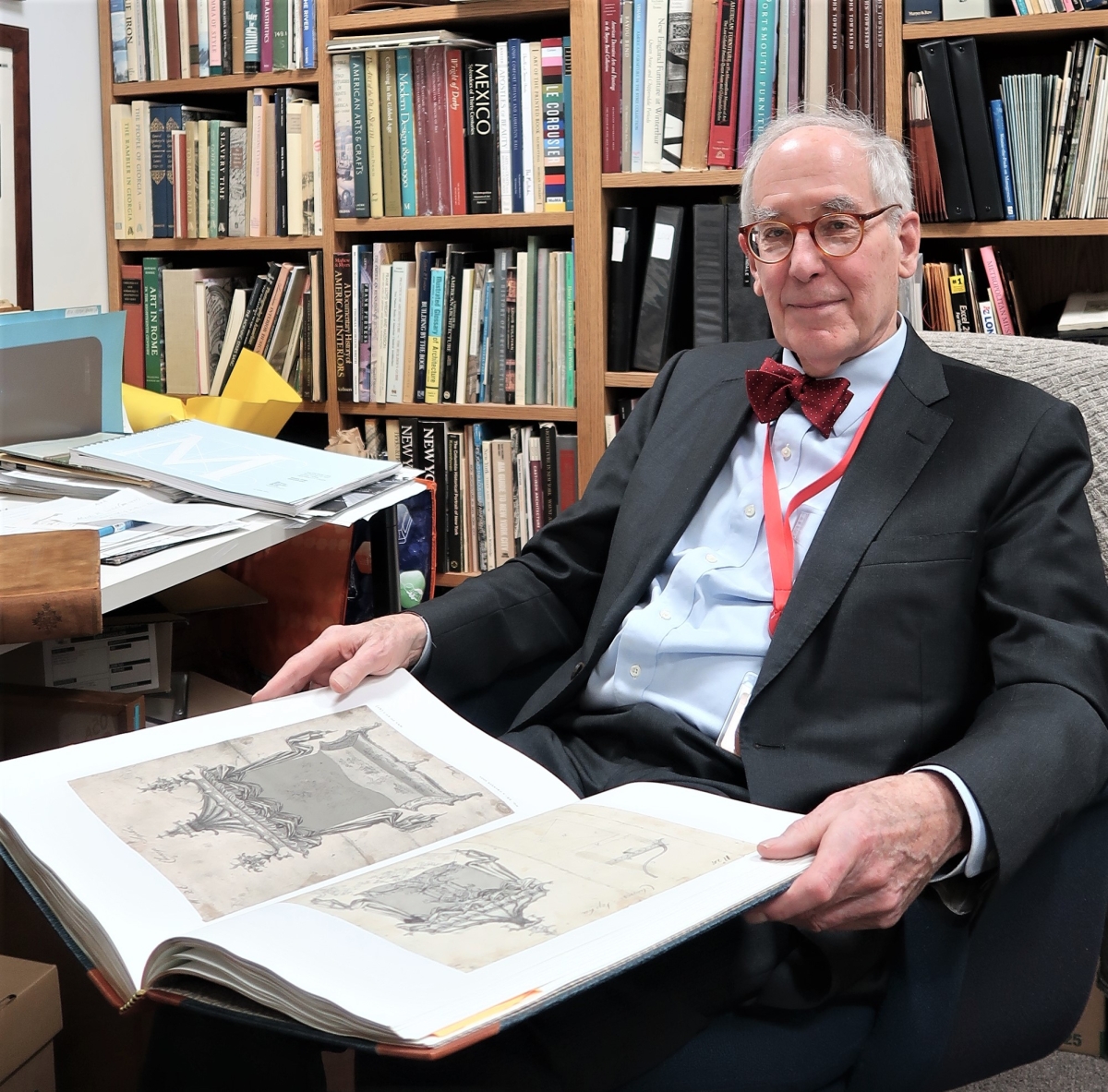

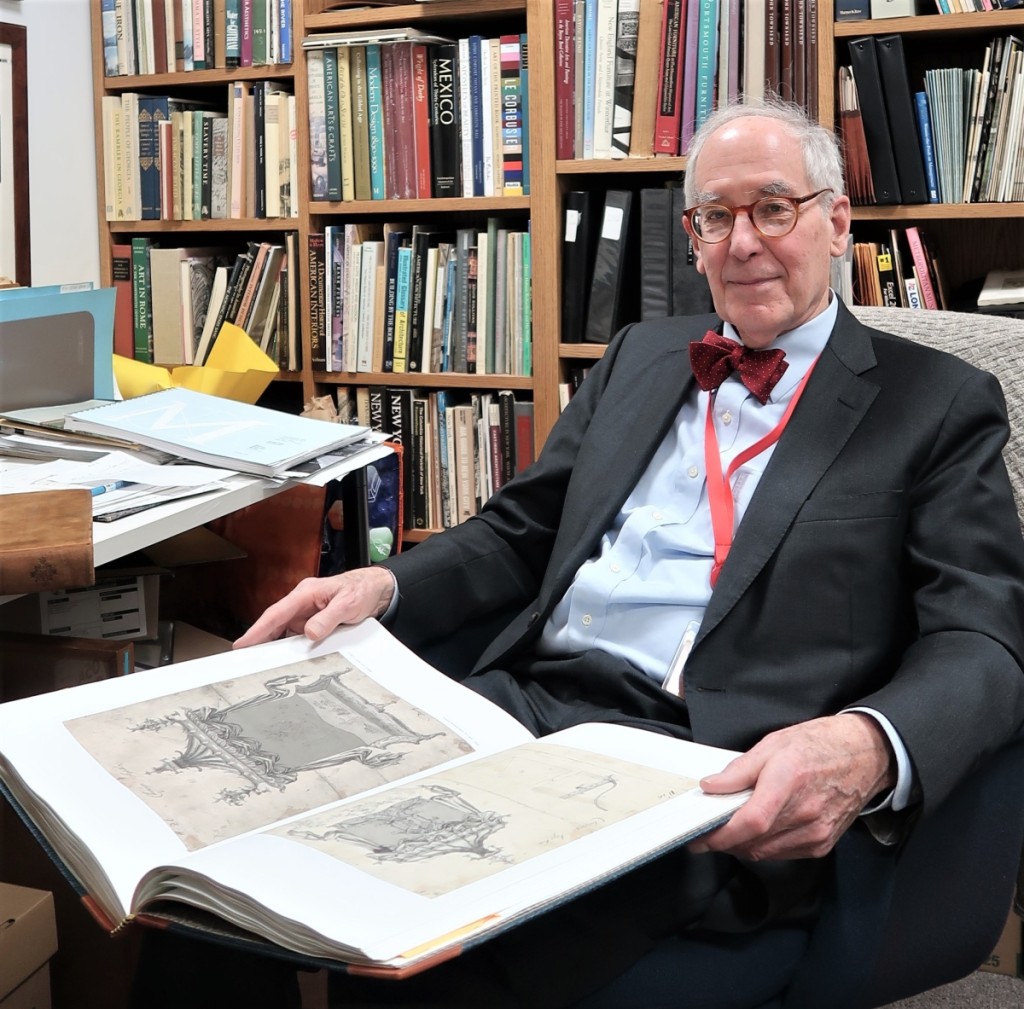

Morrison H. Heckscher, curator emeritus of the American Wing, Metropolitan Museum of Art, undertook the publication of Chippendale’s drawings in honor of the 300th anniversary of the cabinetmaker’s birth in 2018. He first saw the drawings in the Met’s prints department in the 1960s.

Review by Laura Beach, Photos Courtesy of Thornwillow Press and the Metropolitan Museum of Art

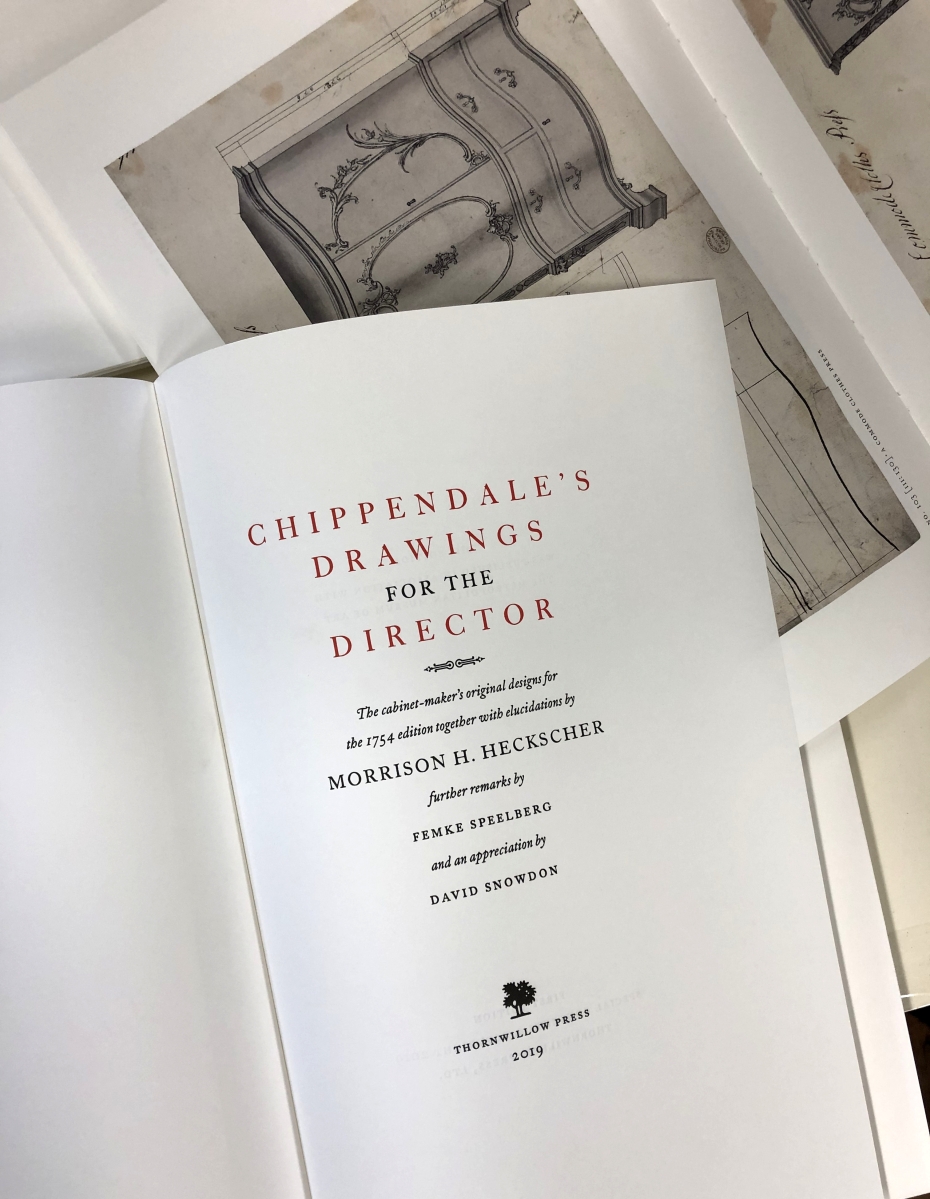

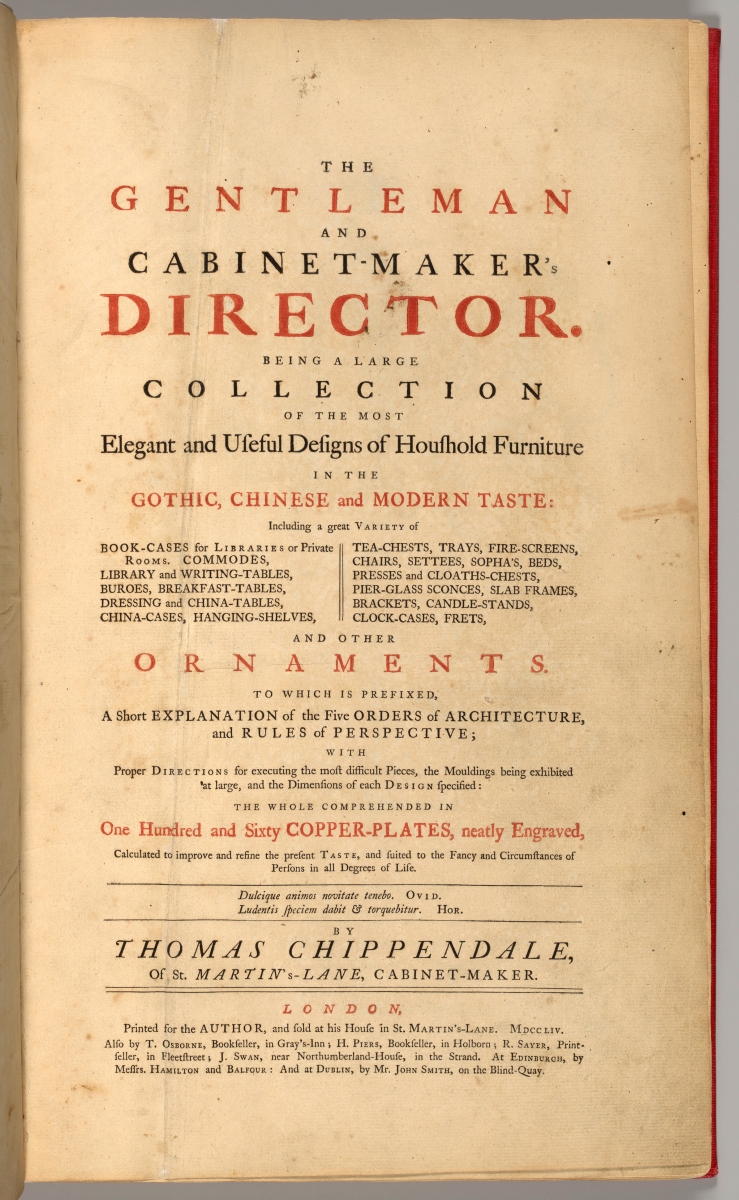

NEWBURGH, N.Y. – One of the great puzzlements of the Chippendale story is how Thomas Chippendale (1718-1779) became a household name throughout much of the English-speaking world without leaving a single piece of furniture known to have been made by the master himself. The answer – provided by Morrison H. Heckscher, curator emeritus of the American Wing, Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA), in “Chippendale’s Director: A Manifesto of Furniture Design” (The Bulletin, Spring 2018, Vol. LXXV, No. 4) – can be summarized in a single word: branding. Quite simply, it was Chippendale’s look-book, The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, first published in 1754, that catapulted the gifted designer to fame.

Published in three editions during the artist’s lifetime and today widely, if partially, available as a Dover reprint, the Director, a collection of engravings after Chippendale’s original drawings, is the most famous Eighteenth Century English furniture pattern book. But what of the drawings themselves? As it happens, they disappeared from public view until 1920, when the MMA acquired the lion’s share of drawings for the first edition’s 161 plates at Anderson Galleries’ auction of the inventory of the late bookseller George Smith, who only a few months earlier purchased the drawings at an English country-house sale. When another six first-edition drawings surfaced at Sotheby’s in London in 1972, three went to the Chippendale Society in Leeds and two to Paul Mellon on behalf of the Yale Center for British Art. The MMA was intent on having the sixth, Plate 16, the design source for a pair of “ribband back chairs” in the museum’s collection. The other major holding of Chippendale drawings, purchased directly from descendants of Matthias Lock, is at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

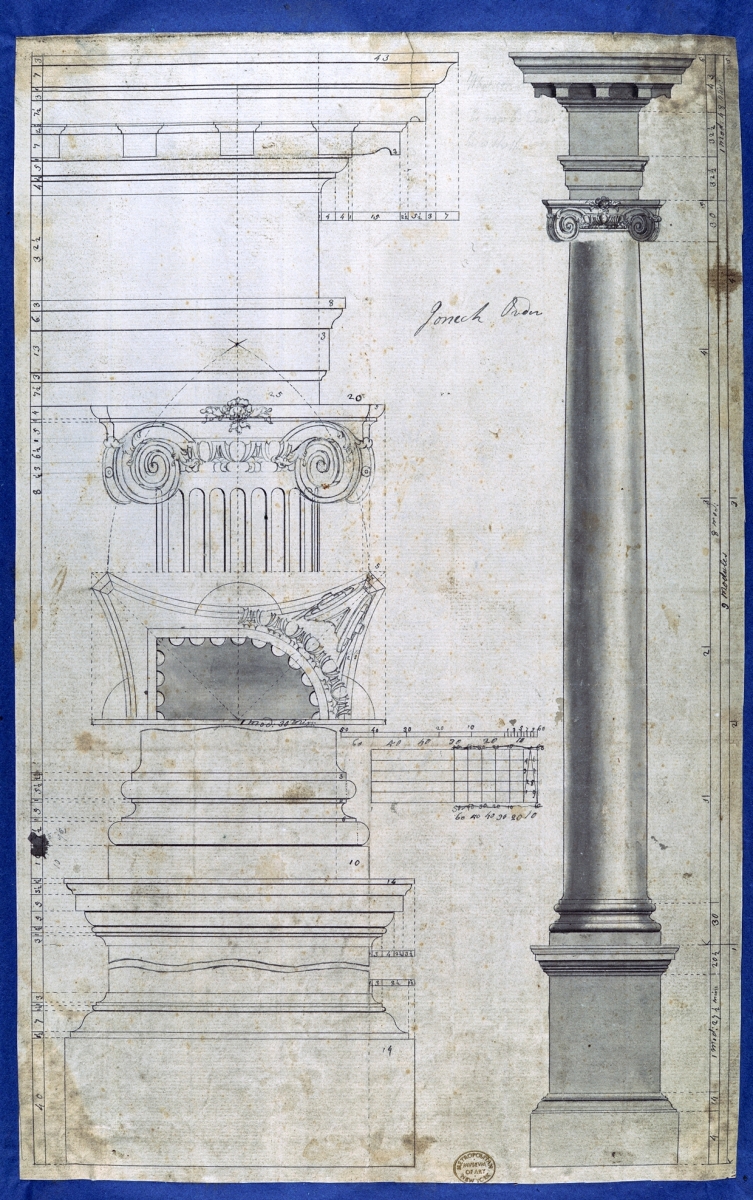

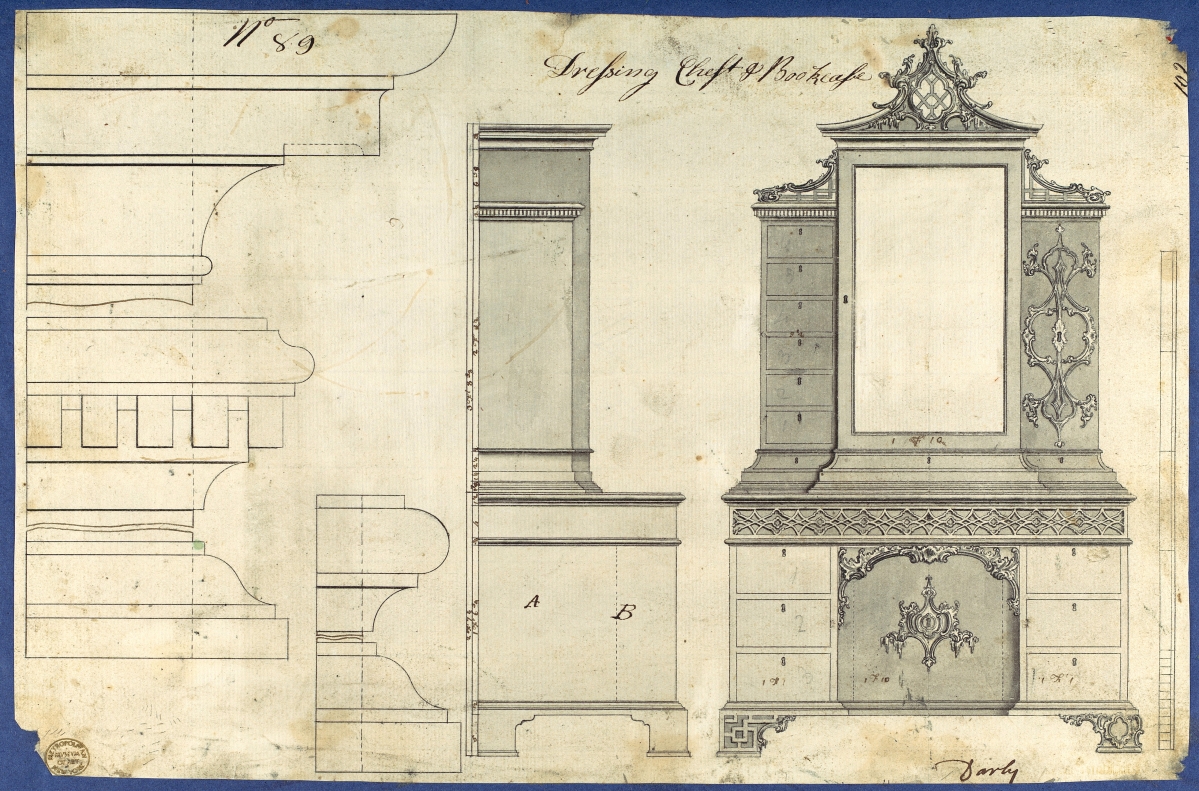

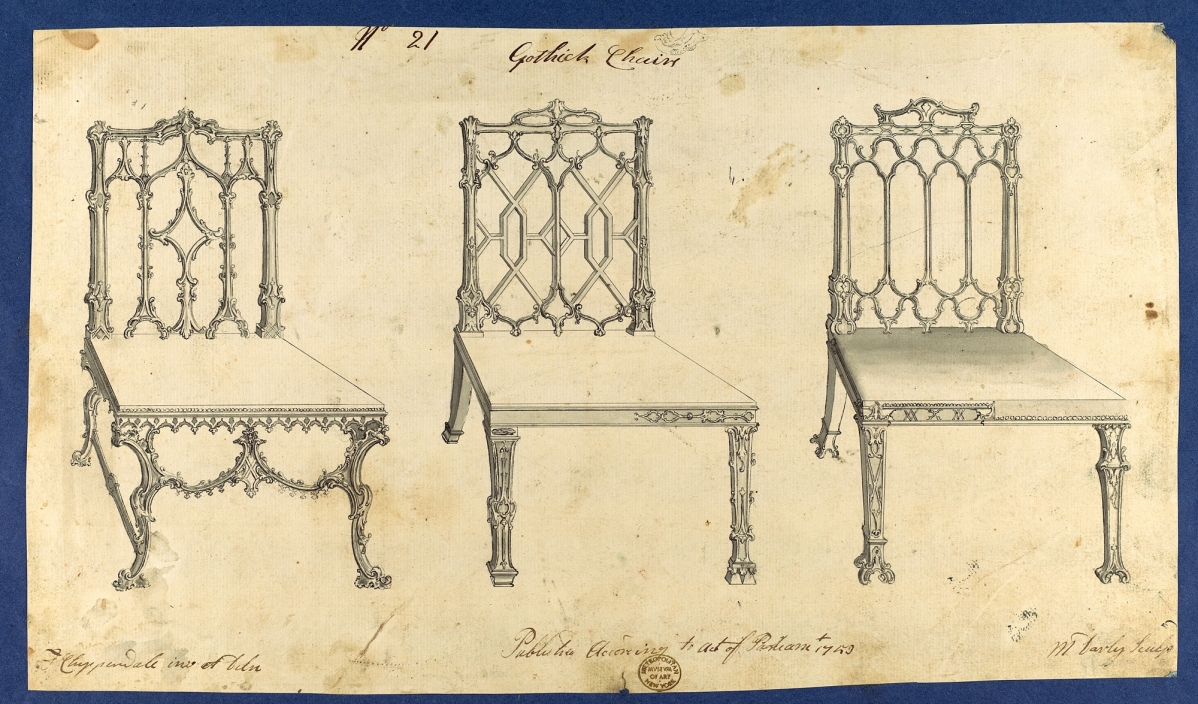

As preparations for tercentennial celebrations of Chippendale’s birth got underway, Heckscher sought to honor the designer by publishing for the first time exact reproductions of the rarely seen drawings, exquisitely rendered in pencil, ink and wash and so laced with inscriptions as to provide insight into the maker’s thinking. Chippendale’s venture into publishing was nearly unprecedented. He sketched objects from the perspective of a standing person, either at three-quarter angle or straight on, as a way of teaching craftsmen to realize Gothic, Chinese and “Modern,” or rococo, designs in three dimensions and in wood. Heckscher writes that the drawings – in contrast to the “technically perfect, stylized and anonymous” engravings – “are vibrant and expressive: how precise the penciled geometry, how elegant the inked line, how effective the washed shadows, how unlike the rote work of a draftsman preparing somebody else’s sketches for the engraver… They are, in short, essential to the canon of craft and design.”

Chippendale funded his publication with contributions from 308 subscribers. Heckscher emulated the craftsman’s approach, securing grants of $10,000 each from 25 patron-subscribers, many of them prominent collectors. The funds went toward the production of Thomas Chippendale’s Original Drawings for The Director, published this summer by Thornwillow Press of Newburgh, N.Y., in association with the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

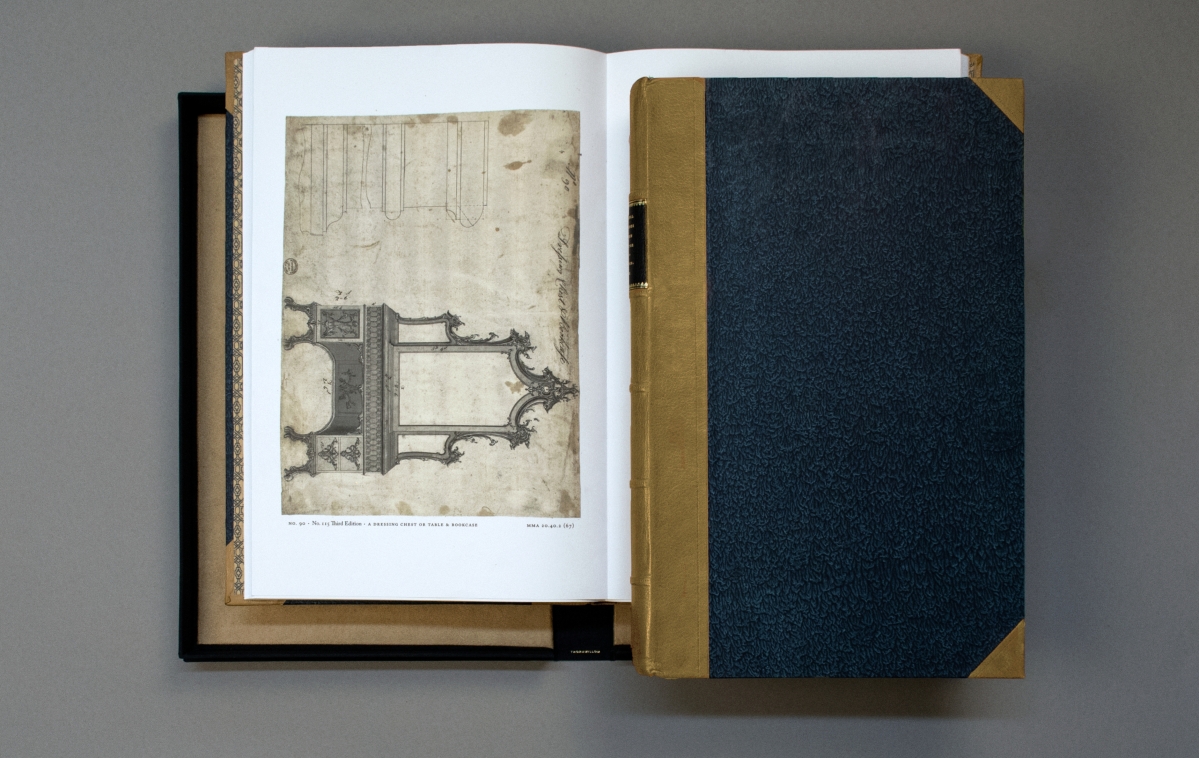

For their support, patron-subscribers will receive what is certain to become a collector’s item: a leather-bound volume inscribed with the patron’s name and enclosed in a clamshell box. Thornwillow is issuing an additional 50 copies, also printed on heavy archival stock, in half-leather and available for $1,850 per copy. Another 75 copies, hand bound in cloth, are priced $425. The print run is limited to 150 copies and advance reservation is suggested. Those who order in the next few days will be listed among the subscribers. Remaining copies, should there be any, will be priced higher.

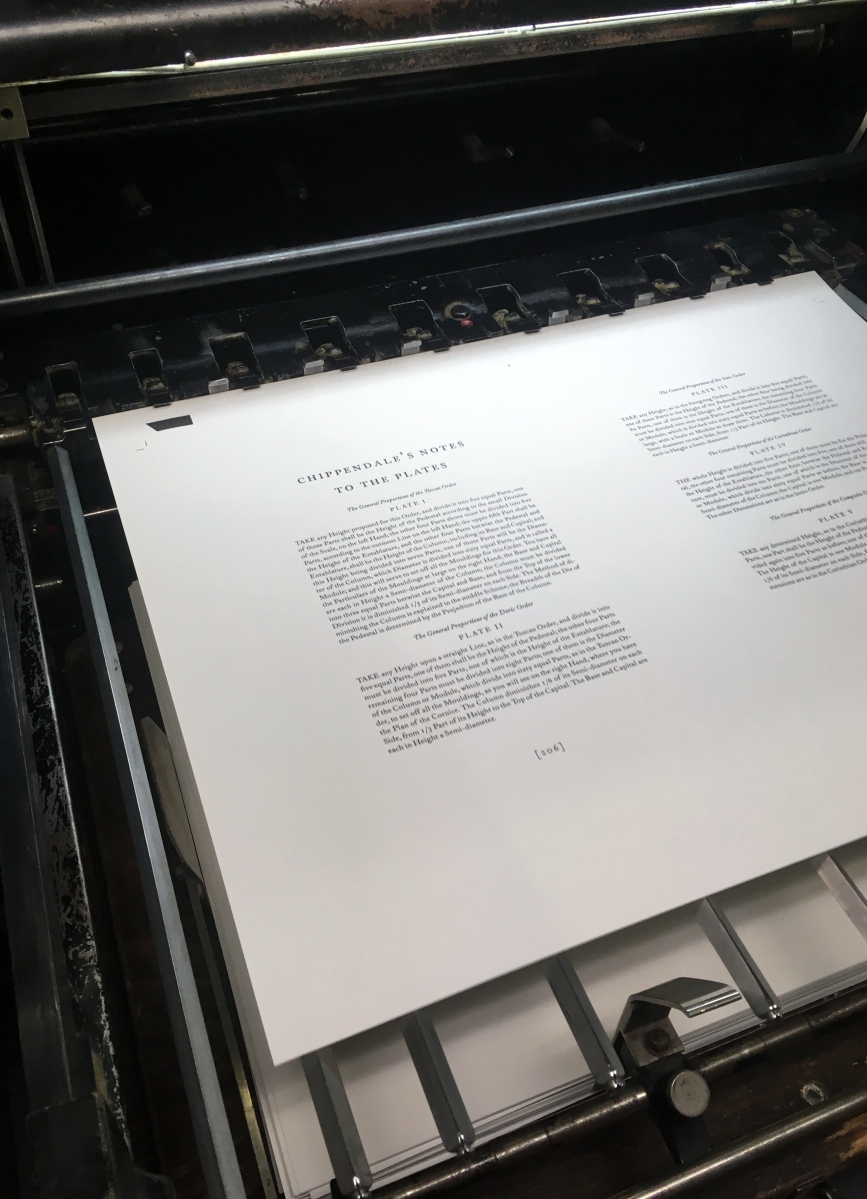

Scholar Morrison H. Heckscher and publisher Luke Ives Pontifell review pages at Thornwillow, the fine press Pontifell operates in Newburgh, N.Y.

Thomas Chippendale’s Original Drawings for The Director hews closely to the format of the first edition, even reprinting Chippendale’s own preface, penned from St Martin’s Lane in London on March 23, 1754. Where possible, the drawings replace the first volume’s engravings, whose order and numbering dictate that of the new publication.

In addition to Heckscher’s introduction, the new work includes a discussion of drawing, design and printmaking in Chippendale’s London by Femke Speelberg. Associate curator in the Met’s department of drawings and prints, Speelberg observes that, while the Director is a testament to Chippendale’s personal ambition, it also reflects the strivings of a nation, adding, “Chippendale demonstrated how a cabinetmaker of humble beginnings could cater to the needs of a wide cross section of British society.”

David Snowdon, the furniture maker and cousin to Prince Charles, provides a personal appreciation. Vice president of the Prince’s Foundation and founder of the Snowdon Summer School, a center for fine-woodworking instruction, the craftsman writes, “Thomas Chippendale created the Director, no doubt, to inspire people like me…you can almost hear his voice explaining how to measure, how to cut and proportion your work. He wants you to understand his technique, detail and craft.”

Chippendale’s drawings have a special resonance for Heckscher, a scholar of Eighteenth Century American furniture who began his MMA career in the late 1960s as a Chester Dale Fellow in the museum’s prints department, where he worked with architectural drawings and graphic arts and first encountered these foundational documents. Chippendale, who considered architecture “the very soul and basis” of the cabinetmaker’s art, prefaced his portfolio with instruction on the fundamental components of building, noting, “Of all the Arts which are either improved or ornamented by Architecture, that of Cabinet-Making… is the most useful and ornamental.”

Heckscher found an ideal partner for his project in Luke Ives Pontifell, who founded Thornwillow Press in 1985 as a way of keeping the book arts alive. “Who better than Morrie Heckscher to take you into the world of Thomas Chippendale? You are walking in Chippendale’s footsteps with the ultimate guide,” says the publisher. Thornwillow’s projects, which cover a broad range of cultural and historical topics and draw on the expertise of noted experts, often depend on contributions from their communities of interest.

“Chippendale is all about making beautiful objects. This edition comes from the same spirit. It’s a tiny edition, immensely costly to produce, and not just from the letterpress printing and binding aspect of the project. The facsimiles, all in the original size, capture the colors and tonality of the ink and pencil drawings immaculately. The irony is that for all the work done on computers, this was in every way an endeavor of handcraftsmanship,” says Pontifell, whose team labored to perfect digital files created from newly commissioned photographs of the drawings.

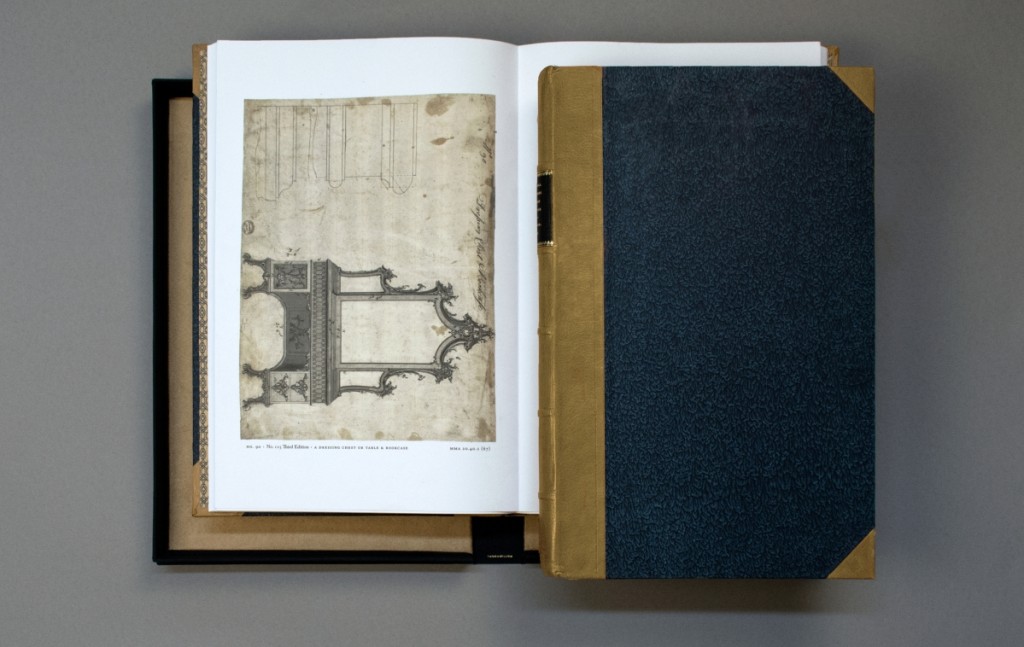

State-of-the-art digital files were used to create facsimiles of the original drawings in Thomas Chippendale’s Original Drawings for The Director. The drawing for Plate 90, a dressing chest or table and bookcase, shown here, is in the Met’s collection and appeared as an engraving in all three editions of the Director.

Thornwillow reproduced facsimiles of the drawings via offset lithography on vellum stock that is the same weight as that used for the 1754 edition. After setting the type in-house, Thornwillow printed text pages on a vintage Heidelberg flatbed cylinder press. Pages were then folded and sewn, bindings stitched and edges finished in gold. The full-leather bindings are in calf, sponged to create the mottled texture of an Eighteenth Century volume. The cloth version of the book is covered in an indigo-blue fabric whose hue is inspired by the album pages on which the MMA’s drawings are preserved.

The Chippendale story has not been without its stops and starts. Heckscher explains that, were it not for the Revolutionary War, Philadelphia cabinetmaker John Folwell might have succeeded in printing his American “Chippendale,” the proposal for which was bound into some copies of the Philadelphia edition of Abraham Swan’s British Architect in 1775.

Likewise, scholars Desmond Fitzgerald of the Victoria and Albert Museum, Christopher Gilbert at Temple Newsam House and William Rieder of the MMA long dreamed of seeing Chippendale’s drawings in print. Bringing the project to fruition nearly 50 years later is for Heckscher both an elegant summation of his life’s work and a remarkable conjunction of kindred spirits past and present.

Heckscher says simply, “It was a loose end I was thrilled to be able to close because these drawings are one of the great treasures of the Met’s collections.”

To reserve a copy of Thomas Chippendale’s Original Drawings for The Director, contact Thornwillow Press at 845-569-8883 or visit www.thornwillow.com. Thornwillow Press is at 25 Spring Street in Newburgh, NY 12550.