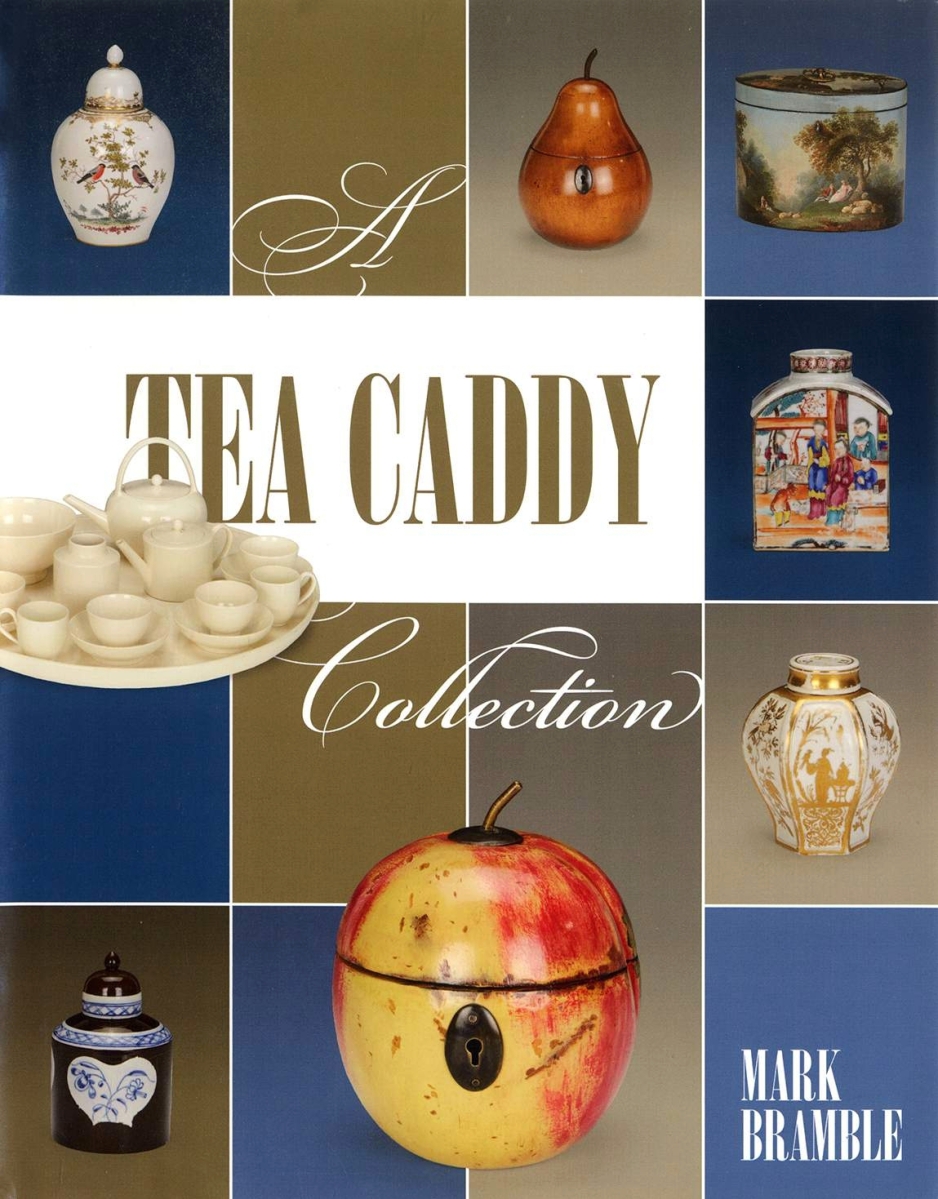

By W.A. Demers

ODESSA, DEL. – On December 16, 1773, a group of political protesters in Boston – the Sons of Liberty – threw an entire shipment of tea sent by the East India Company into Boston Harbor. Theirs was an act of outrage, provoked by the British Tea Act that was put into place the previous May, and which colonists believed to be “taxation without representation.” His Majesty’s government was not amused by the “Tea Party,” and the episode helped bring the simmering enmity between America and England to a boil, sparking the American Revolution.

Pennsylvania Quakers had a different idea. Just nine days later, on December 25, 1773, the British tea ship Polly sailed up the Delaware River en route to Chester, Penn., with a cargo of 697 chests of tea consigned to a Philadelphia Quaker firm. Being Quakers, they took a less confrontational approach toward the British, and instead of boarding the ships like their Boston brethren, they met and determined that “the tea shall not be landed.” The kettle was not put on, and Polly and her tea were sent back down the Delaware River into Delaware Bay and back to England.

The resonance created by the fact that the Historic Houses of Odessa overlook the Appoquinimink River, a tributary of the Delaware River where Polly and her precious cargo were rebuffed, is not lost on author and theater director Mark Bramble, whose collection of tea caddies is the focus of an exhibition on view in two of the Historic Houses of Odessa through August 26.

Bramble, the creator of hit Broadway musicals, including the Tony Award-winning 42nd Street and Barnum, has a prodigious collection of more than 400 of these compelling containers. The exhibition features more than 200 Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century tea caddies from Bramble’s vast collection, augmented by a dozen or so examples in Odessa’s permanent collection.

Bramble’s collection began more than half a century ago, when his mother, Marnie Bramble (1918-2015) of Chestertown, Md., began acquiring them, enlisting her youngest son in her hobby. It is in Bramble’s words, “an incredible thing for a parent and child to share.” Antiques and The Arts Weekly asked Bramble to talk about some of the examples on view in the exhibition, but let’s start at the beginning:

Marnie Bramble’s first tea caddy.

“The first caddy she found at an antiques fair in Easton, Md., without knowing what the little jar was. My mother was a petite person, and she said that as a small person she was attracted to small objects and was drawn to its charming shape and size. She soon found out that it was an Eighteenth Century Chinese export tea caddy – and thus began her lifelong quest to learn about and collect tea caddies.”

—

English Worcester porcelain tea caddy and teapot, circa 1770, with blue scale ground and rococo panels framing Kakiemon-inspired decoration.

“The tea caddy came from a dealer in New Jersey, and I found the teapot in London. What’s fascinating about these pieces is the dark blue ground, which turned out to be a very difficult color to achieve because the blue ran quite easily. What Worcester developed was something they called ‘blue scale.’ Rather than painting a background of solid blue, the background is made up of hundreds of tiny scales. The painting on these pieces is inspired by the Japanese artistry and the gilt is then applied last. Interesting to me, the gilt comes off quite easily. The scales and the paint are exactly as they were 250 years ago.”

—

A rare Wedgwood creamware child’s tea set, circa 1770-90.

“Mother and I found this at a dealer in New York, Leo Kaplan Sr. Mr Kaplan and my mother got along very well. The tea caddy is missing its lid, but otherwise the set is almost perfect. What’s extraordinary to me is that if it was made for a child, no child today would have taken such great care of the set. It makes me wonder if these were really made for children or as an adult collectible.”

—

Extremely rare English fruitwood tea caddy in the form of a peach, which has amazingly retained most of its original paint, circa 1790.

“The peach is the rarest form of the fruit caddies. It’s such a beautiful object and for something that was made in about 1790 to have retained its original paint is remarkable. None of the other fruit caddies in our collection have retained more than traces of their original paint. What is also fascinating to me is that there is no known record of these fruit caddies being manufactured or sold. So, it leads one to think that perhaps they were ‘home made’ on grandfather’s hobby bench.”

—

English George III papier mâché tea caddy made by Henry Clay, circa 1775-1800.

“Henry Clay developed this form. Today we think of papier mâché as something kids make in grade school. In the Eighteenth Century, it was a very viable material to make things out of, including carriages and sedan chairs, helmets, shields. Clay took the material one step further to make it more resistant to dampness, heat and so on. We have no concept of tea being as precious as it was in the Eighteenth Century. It was as precious as gold. If you were fortunate enough to have tea, you prepared it a table in the presence of your guests and showed it off in a decorative container. That’s why these pieces are so artfully rendered.

“A dealer in England had this particular caddy, and for several years, I corresponded with him trying to negotiate a price. It always ended up being out of reach. Nevertheless, every six months or so I would write to him inquiring about it. Then about 18 months ago I looked at his website and the piece was gone! And I thought, ‘You fool, you should have gotten that.’ A couple of months later I checked again and it was back on his website. We finally agreed on a price and to seal the deal I included a pair of seats for the opening night of 42nd Street in London last April.”

—

Dutch Delft rectangular tin-glazed earthenware with chinoiserie decoration, circa 1700.

“This is the oldest caddy in our collection. It was made at a time when Chinese export trade had stopped. At the end of the Ming dynasty, trade with China became very complicated. The Chinese put too many obstacles in the way and there was also a tremendous problem with pirates. Chinese pirates would seize the booty and sell it to tradesmen of other nationalities. So the Delft factories developed a way to make thinner pieces and by coating them with tin oxide glazes were able to create a good likeness to porcelain. This piece is an example of that – it’s stoneware that has been glazed and decorated to look like Chinese export.

“Interestingly, this piece’s neck is threaded so it originally had a screw top, which is unusual in my experience. The silver top that’s on it now is a replacement.”

—

English fruitwood tea caddy in the shape of a pear, circa 1790.

“This piece has a hole in the bottom that has been plugged. Not only is it a glimpse into its manufacture but it’s also a way you can tell old ones from not-so-old ones. There are a limited number of authentic fruit forms around; they are valuable and worthy of counterfeiting. Many of the counterfeits come out of Germany, where some of the fruit caddies were made in the Eighteenth Century.

“Also, this piece has traces of its original lead lining. It would be locked to protect the contents from light-fingered servants, and the key was held by the mistress of the house. The lid is hinged at the back, so that one would – with a tea caddy spoon – scoop out the amount of tea you wanted to use.”

—

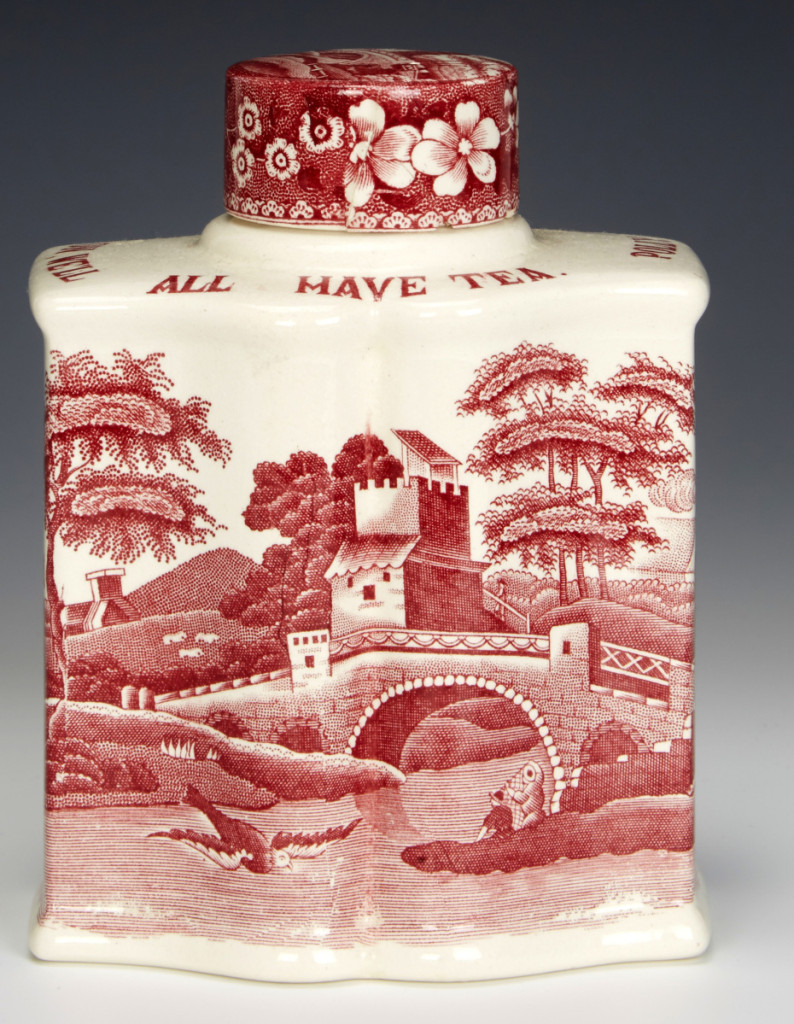

English stoneware tea caddy, circa 1910, with red transfer decoration.

“This one is quite a bit later. On the top is written ‘Polly put the kettle on, we’ll all have tea’ from the Mother Goose nursery rhyme. On the lid of this piece, at the center, you can see the seam in the transfer decoration. You see the flower, and the flower is cut off the left side, which illustrates the transfer technique.”

—

Set of three English Georgian sterling silver tea caddies and covers, circa 1760. Made by silversmiths Daniel Smith and Robert Sharp.

“The two on either side are for tea – one for black tea and the other for green tea. The center container, which is slightly larger, was used for to store sugar. When these were made they would probably have had a lockable wooden chest to store them. These were found in Edmonton, Canada, when I was there working on a musical version of Treasure Island.”

—

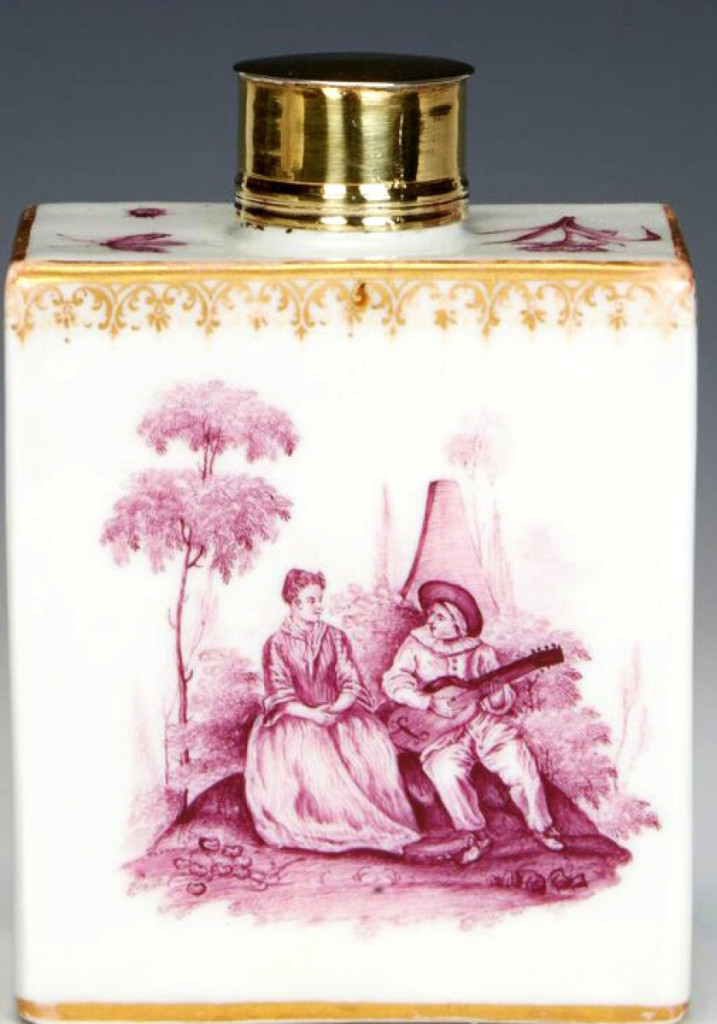

German Meissen tea caddy, circa 1745, wonderfully painted with scene from the commedia dell’arte with Pierrot serenading Columbina.

“What’s fascinating to me about this piece is the decoration. The scenes are inspired by Antoine Watteau’s painting, and the technique is called ‘camaieu,’ which uses different shades of the same color to create a sense of depth and dimension. And it is fascinating to me because the artist has such a small surface on which to paint and the detail is quite extraordinary. The gilt border around the shoulder is typical of the rococo era.”

—

An ode to Bramble’s 42nd Street ‘s chorus line, all 24 “dancers” in this grouping are Chinese export rectangular sloped-shoulder tea caddies, circa 1775-90.

“This rectangular slope shouldered form represents one of the most popular – if not the most popular – forms of Chinese export tea caddy produced in the Eighteenth Century. I lined them up in a tribute to my show 42nd Street, which has a cast that includes 24 girls.”

—

Large English wooden tea caddy in the form of a pineapple, circa 1870.

“As you can see, the paint on this piece is flaking badly. Every time we touch it, it seems like a little more of the paint flakes off. So it is presently in the ‘hospital’ – an art restorer in Baltimore – where specialists are working to preserve the paint. It will join the exhibition that is currently on view a few weeks after it opens.”

The loan exhibition “As Precious as Gold: A History of Tea Caddies from The Bramble Collection” is free with admission to the Historic Houses of Odessa, a 72-acre enclave of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century structures located just two miles from DE 1 and just off US Route 13 in southern New Castle County. For information, www.historicodessa.org or 302-378-4119.

Unless otherwise noted, all photos are by Benny Cuppini.