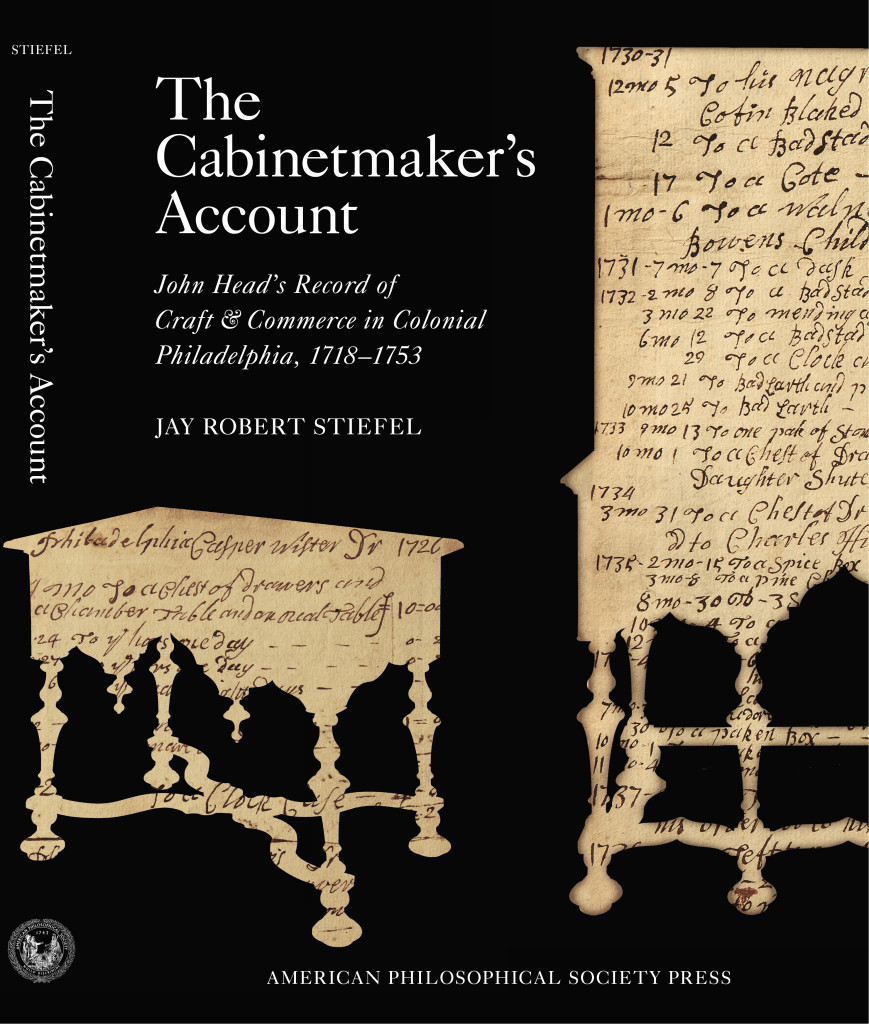

Jay Robert Stiefel, The Cabinetmaker’s Account: John Head’s Record of Craft & Commerce in Colonial Philadelphia, 1718–1753, Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society Press, 2019, large-format, 320 pages, 100 color and b&w illustrations, hardcover, $85.

Jay Robert Stiefel, The Cabinetmaker’s Account: John Head’s Record of Craft & Commerce in Colonial Philadelphia, 1718–1753, Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society Press, 2019, large-format, 320 pages, 100 color and b&w illustrations, hardcover, $85.

John Head’s account book is one of the earliest and most complete records of a cabinetmaker’s work to have survived in either North America or Great Britain as well as the first related to production in Philadelphia, making it an invaluable archival survivor of historical significance. Comprising 231 pages with thousands of meticulously recorded entries for hundreds of clients, the book is a concise overview of how Colonial Philadelphia artisans operated within a barter economy.

The account book was part of a large collection of papers from the Vaux Family that was given to the American Philosophical Society in 1991–92. In his “Note from the Librarian,” Patrick Spero, librarian and director of the APS Library, states that the Vaux family papers comprise “one of the largest uncataloged early American collections at the Society… a total of nearly 150 linear feet.” It was by chance that Stiefel discovered the book nearly two decades ago while looking through the Vaux papers for other material. Since then, Stiefel has not only parsed the frail crumbling pages of the volume, but he has combined information from primary sources that provide not simply a sketch of Eighteenth Century Philadelphia working practices, but a roadmap for discovering objects connected to his shop. Because of Stiefel’s research, John Head enjoys a considerably more prominent standing in the community of Philadelphia craftsmen than he had previously been awarded in 1935, when he received a single-line entry in Hornor’s Blue Book, Philadelphia. Now, more than 60 pieces can be attributed to Head’s shop, and he can take his rightful place among the names of identified cabinetmakers whose production and output has been an important part of early American material culture.

Stiefel’s enthusiasm for the material is evident throughout the catalog, but perhaps nothing more clearly elucidates his elation at finding the book than when he equates it with the moment when Howard Carter opened Tutankhamen’s tomb. This enthusiasm is indeed evident in the way Stiefel has turned what Adam Bowett calls in his foreword “among the least congenial forms of manuscript” into an interesting, even evocative, read. In outlining the trade practices and record-keeping habits of the time, Stiefel not only highlights the problems facing researchers and scholars of early American decorative arts, but also suggests alternative methodologies and research avenues to investigate. This will surely have greater applications and ramifications for the future.

The Cabinetmaker’s Account is not a catalog raisonné of Head’s work, but it provides the fullest context possible around not just the cabinetmaker and his production, but the society in which he worked. Many of the items that can now be confidently attributed to Head’s shop feature prominently in the later chapters of Stiefel’s book, where he cites or illustrates examples of each of the forms that Head’s shop produced. These are just a fragment of the output of his shop, but they provide the guidelines for future discoveries.

The appendix of the book adds some additional perspective to Stiefel’s book in naming the existing account books of other British American cabinetmakers who were peers of John Head. These are limited to the chairmakers of the Gaines Family of New Hampshire, 1707–62, and Thomas Pratt of Massachusetts, 1730–68 (both at Winterthur); the cabinetmakers Joshua Delaplaine of New York, 1720–78 (New-York Historical Society), Joseph Brown, 1725–86, and the Lunt Family of Massachusetts, 1736–72 (Essex Institute); the joiner, Joseph Lindsey of Massachusetts, 1739–73 (Winterthur); and Thomas Fitch, the upholsterer, starting in 1719 (Massachusetts Historical Society). This brief finally underscores not only how rare a survival Head’s account book is, but further demonstrates its contribution — and potential for additional influence on the field of early American decorative arts.

—M.H.R.