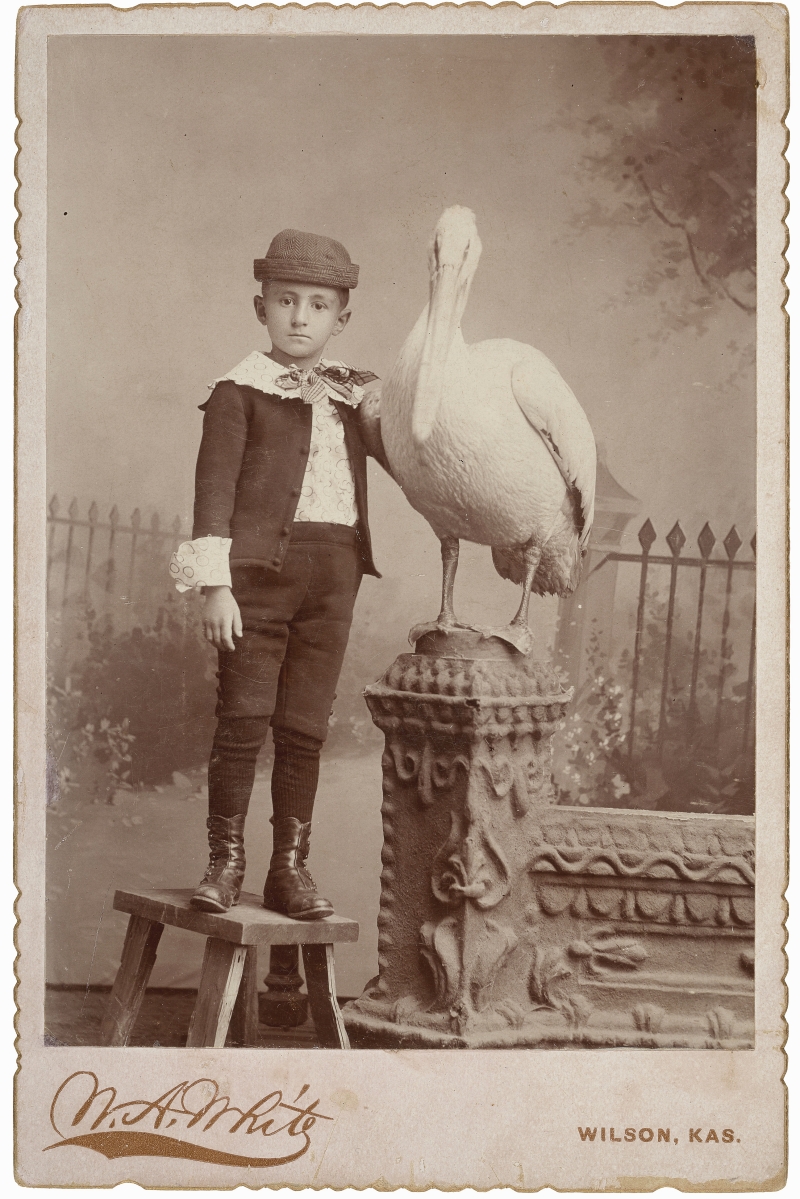

“My first baby friend Tompie and his pet” by W.A. White, Wilson, Kan., 1896. Collodion silver print. Robert E. Jackson Collection.

By James D. Balestrieri

FORT WORTH, TEXAS – I hope someone – lots of someones, actually – is capturing screen shots of Zoom, FaceTime, Messenger and Google meetings. You know the ones: the family get-togethers that devolve into political shouting matches; the business meetings where everyone looks as if they are under the hot lights in a Kafka novel, whether they are wearing pants or not; the kids’ classes where the mute button doesn’t dampen the din; the readings of new plays and musicals where some of the squares freeze and then the whole thing is just a bit… off. Imagine The Brady Bunch and Hollywood Squares live and improvised from your grandmother’s basement, unrehearsed, unhinged and unretouched. It’s the image that sums up 2020 perfectly. I have a few of these, surreptitiously taken. But a hundred years from now, if you could gather a few thousand of them, you could make some assumptions about our times, about our desperate attempts to continue what we thought was the business of life and recreate a semblance of normalcy, even after normalcy turned out to be an illusory house of cards blown down by viral breath and viral breathlessness.

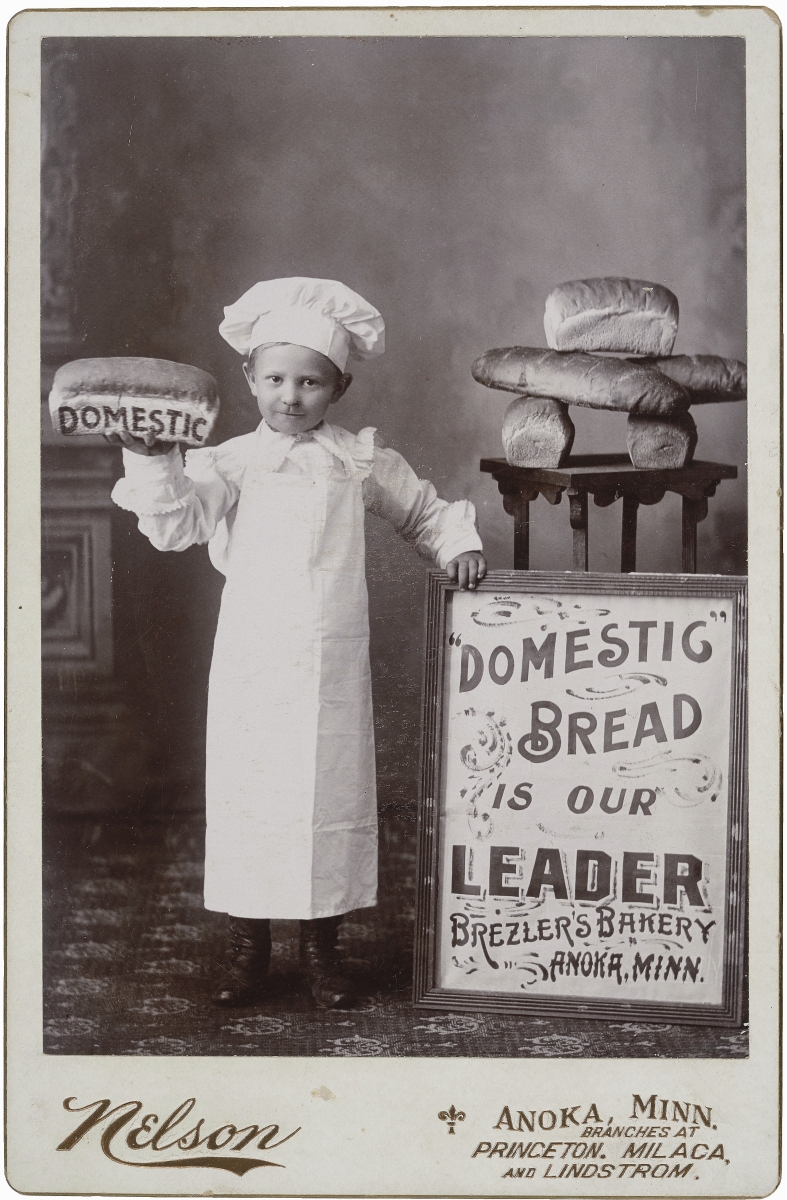

House of cards. Cut the squares apart and mount them in an album. Roll time back to the second half of the Nineteenth Century, to the era of the cabinet card photograph, the first, true, mass-produced images of the self, created not with the exactitude of likeness or the eternity of the portrait in mind, but with the brevity – and levity – of the moment as its object. This phenomenon is the subject of the neat and timely new exhibition, “Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography,” presented by the Amon Carter Museum of American Art from August 18 through November 1 before moving to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Art can evolve out of science. Rapid development followed the birth of photography in France in 1826, but always with an eye to scientific value, to irrefutability, to the medium’s ability to copy nature exactly.

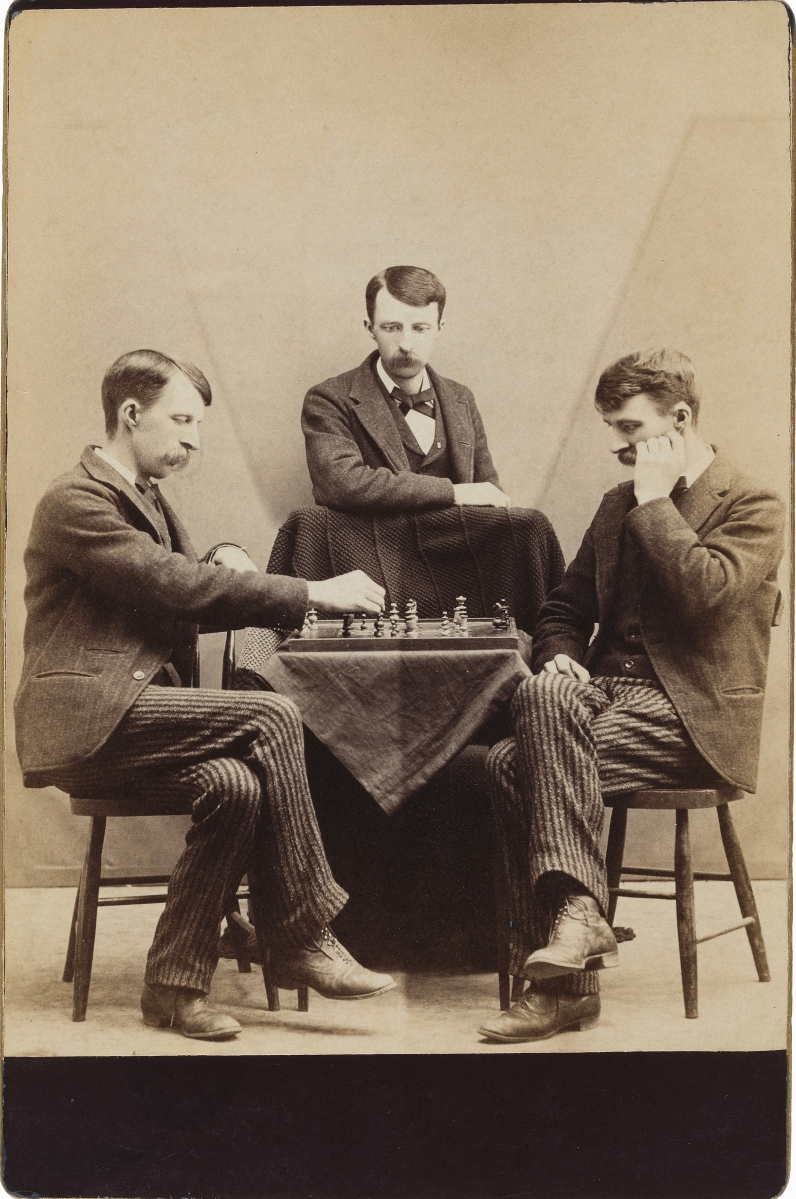

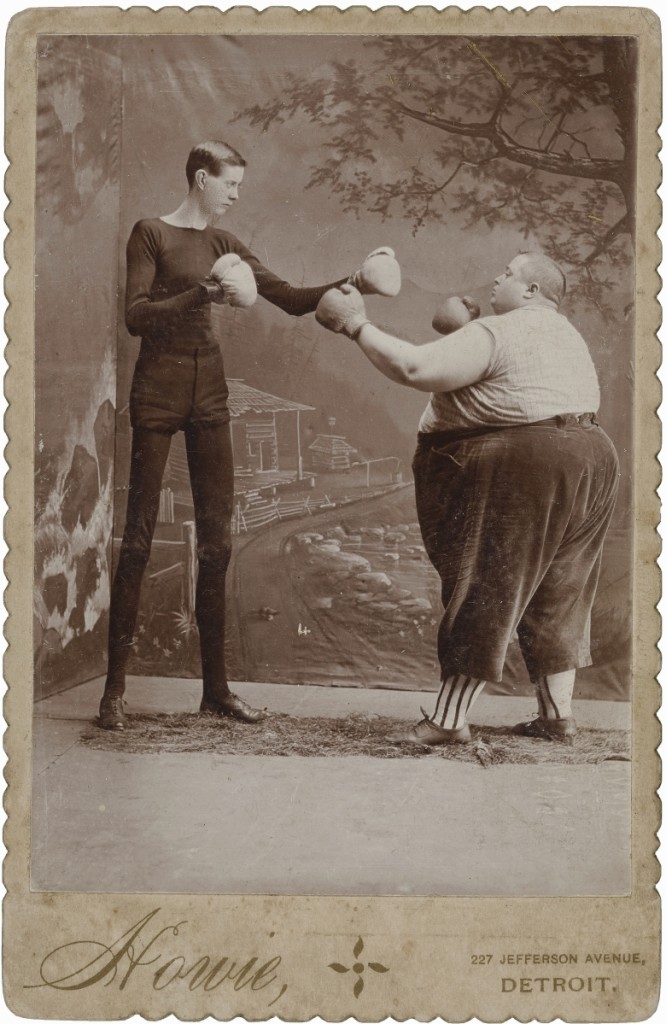

“George Moore and Fred Howe” by Howie, Detroit, Mich., 1890s. Collodion silver print. Robert E. Jackson Collection.

In human portraiture, however, the length of exposure time meant that the subject had to sit perfectly still for a long period of time. Thousands of cartes de visite still exist, and they remain an important record of people whose faces we might otherwise not know at all. American poet Emily Dickinson springs immediately to mind. Yet even as the tin daguerreotype evolved into the paper-backed carte de visite, the people in these photographs, despite their popularity, seemed then – and still seem to us – no more real than a stuffed squirrel beside its animated kin.

But after 1865 and the end of the Civil War, a number of factors came together to propel photography from the realm of science and likeness to the realm of art and liveliness.

In England, an enterprising picture-maker made a simple adjustment in format, enlarging the business card sized carte de visite into a 5¼-by-4-inch paper image mounted on a 6½-by-4¼-inch card (slightly larger than a cell phone) that displayed nicely in Victorian cabinets and thus acquired the name “cabinet card.” At the same time, the process of making photographs became less expensive. Cabinet cards were sold by the dozen and people could – and did – have their pictures taken more often. With less at stake perhaps, a sense of fun and spontaneity emerged in the studios. As John Rohrbach, senior curator of photography at the Amon Carter, writes in the accompanying catalog, “…Cabinet cards transformed photography into a tool for reflecting life. They converted albums filled with carte de visite portraits of extended family into albums documenting every stage of life from babyhood to death.”

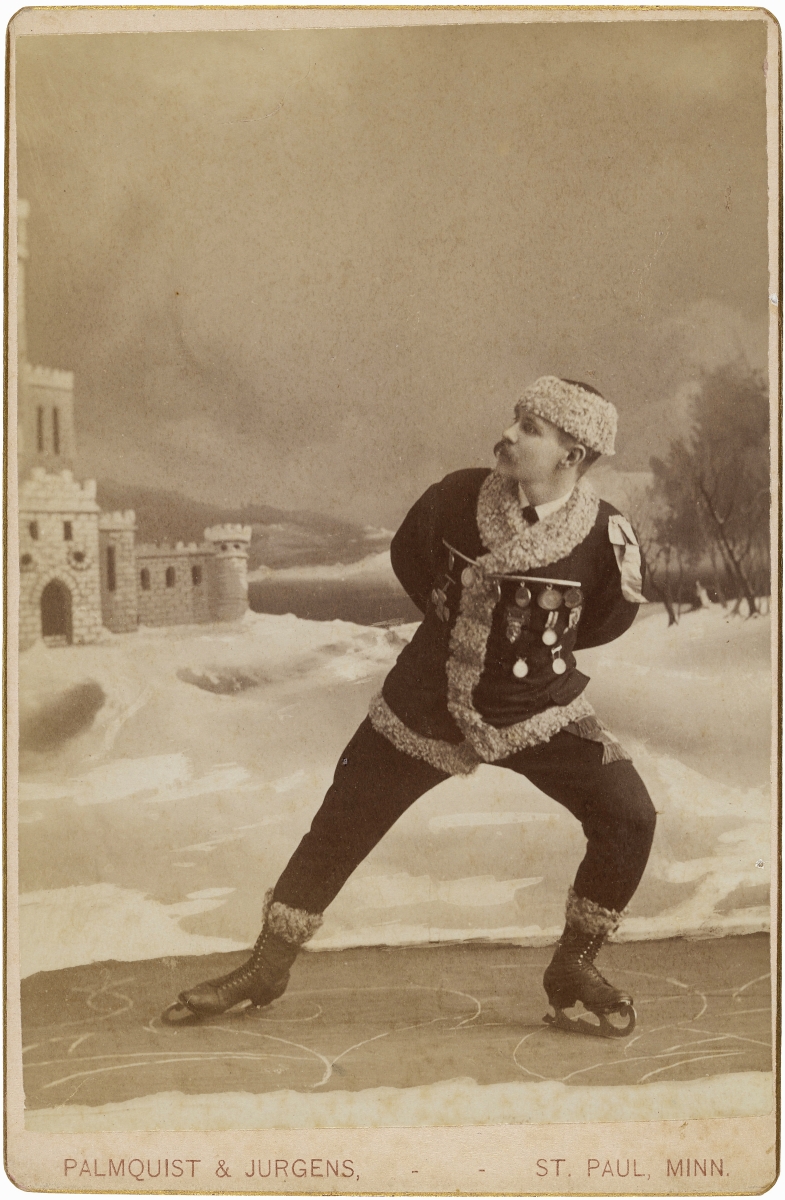

Even small towns had photographers and there were itinerant shutterfolk, just as there had always been itinerant portrait painters. With these larger images, photographers learned to retouch blemishes in the glass plate negatives and to add effects, such as falling snow.

After the Civil War, the theatre, seen earlier as a den of iniquity, became widely and wildly popular with audiences of all persuasions. Photographers, like the flamboyant and pivotal Napoleon Sarony, often shot actors in costume, posed as if in key scenes from popular plays. Theatrical backdrops migrated from the stage, to these actor shots, to the mise-en-scene in cabinet cards of ordinary people who wanted something different, something, perhaps, more representative of their lives and feelings.

Photography still required unusual stillness, but Sarony’s brother invented a flexible posing stand that enhanced the illusion of capturing the subject in motion.

The photography studio became, in effect, both a theatre and a portrait painter’s studio. Sarony, as an example, prioritized artful arrangement in which the subject is part of an overall composition within the frame of the image. Erin Pauwels’ catalog essay describes Sarony in terms we might reserve for an auteur film director: “Like many Nineteenth Century photographers, Sarony did not work behind the camera but rather beside it, employing assistants and darkroom technicians to manage the hands-on work of developing negatives and making prints while he reserved his energies for the more visionary aspects of the job. In this way his role as a photographer more closely resembled that of a stage director…” But as Pauwels dives deeper into Sarony’s approach to his sitters – most of whom stood – we see a hearkening back to the older art of portrait painting: “Sarony explained that “the art of not posing” rested on three key conditions: a photographer’s acquaintance with the sitter’s characteristic expressions, a shared sympathy between photographer and subject, and, most important, subjects having sufficient confidence in a photographer’s abilities to ‘surrender’ themselves completely to his superior judgment. He claimed to begin forming a representational strategy the moment a subject entered his studio. While engaging in casual conversation, he would study their best angles and characteristic modes of expression. If the subject had a crooked nose or a weak chin, he could diminish its appearance through pose and lighting. Then, with these observations in place he would endeavor to recreate a moment before the camera when the subject was carefree and unaware of being photographed, and then snap a quick and candid exposure.”

![“[Skater]” by Alfred U. Palmquist and Peder T. Jurgens, St Paul, Minn., 1880s. Albumen silver print. Amon Carter Museum of American Art.](https://www.antiquesandthearts.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/alfred_u._palmquist_and_peder_t._jurgens_st._paul_mn_[skater]_1880s_albumen_silver_print_amon_carter_museum_of_american_art_fort_worth-670x1024.jpg)

“[Skater]” by Alfred U. Palmquist and Peder T. Jurgens, St Paul, Minn., 1880s. Albumen silver print. Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

This is precisely the sort of strategy that visitors to Van Dyck’s studio in the 1600s often described, careful observation through a casual disarming of the subject. We are not far from Freud’s couch in such territory.

By leaning in to artifice, and delving into psychology, artistry transformed the medium. Photography is now seen as an art as opposed to merely a reproduced reality, yet this artistic reality, ironically, seems to cleave closer to what we call observed reality.

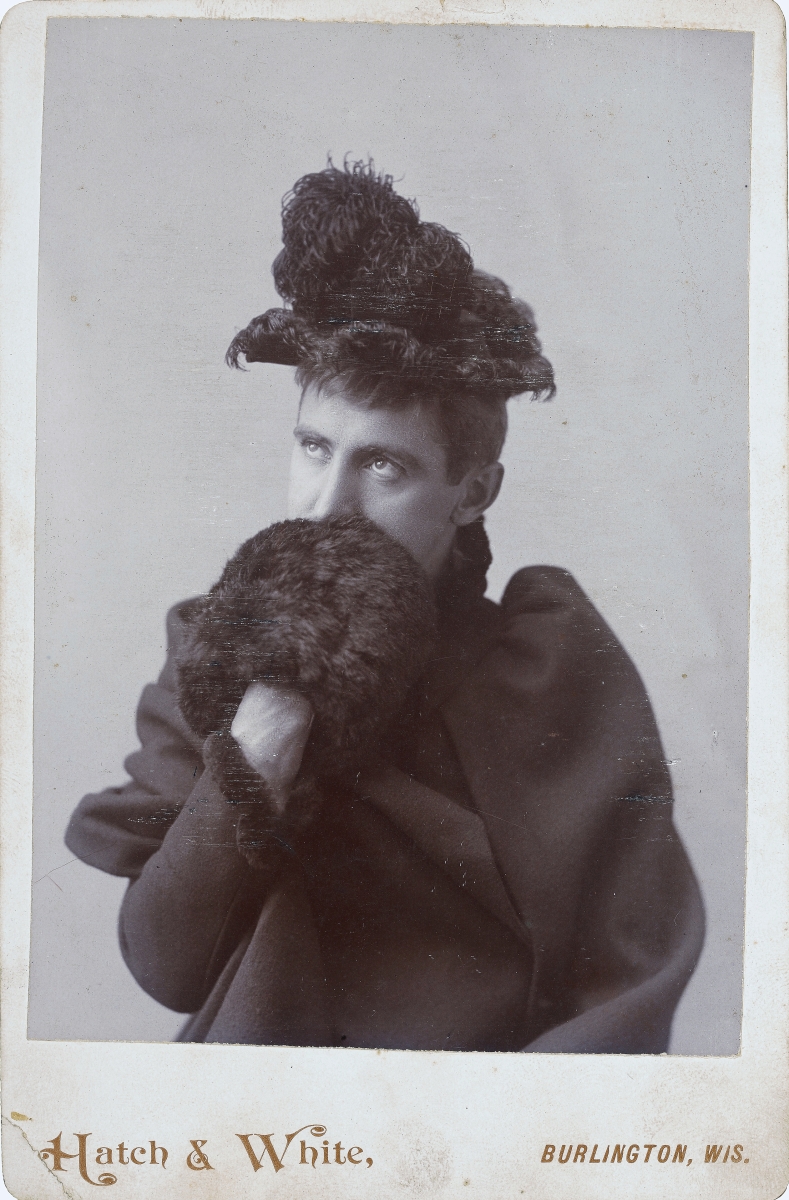

To us, at this distance, looking back, some of these cabinet cards approach the surreal, looking more like stills from one of the early films of Georges Méliès than Kodak snapshots. The photographic studio was a place of fantasy, of brief escape, of refuge. You can see the people in these cabinet cards seeking stillness and cheerfulness, trying, sometimes too hard, to put aside, just for a moment, the hardships of individual lives lived amidst the very real upheavals of the second half of the Nineteenth Century: the failure of Reconstruction and swift emergence of Jim Crow, the decimation of Native Americans, the rise of the Women’s and Labor movements, rapid industrialization, urban slums, economic booms and busts that affected farm and factory alike. Putting themselves in the hands of the photographer, not having to make any decisions, being asked to “Hold that pose,” and “Hold your breath,” might, in its own way, have offered a brief breather, relief from care.

![“[Man in woman’s clothing]” by Hatch and White, Burlington, Wis., circa 1891. Collodion silver print. Amon Carter Museum of American Art.](https://www.antiquesandthearts.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/hatch_and_white_burlington_wi_[man_in_womans_clothing]_ca._1891_collodion_silver_print_amon_carter_museum_of_american_art_fort_worth-673x1024.jpg)

“[Man in woman’s clothing]” by Hatch and White, Burlington, Wis., circa 1891. Collodion silver print. Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

Here’s the difference: when you look at a carte de visite or an even older daguerreotype, you wonder who these people were and you marvel at the sheer survival of the artifact that represents them. But when you look at a cabinet card, you fly past all that quite quickly and wonder what these people were thinking and how their stories, desires and humor, might not be dissimilar to your own. This is the aesthetic of the snapshot and the selfie, and of the great photographs of the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries. As staged as they might be, they reveal even as they conceal, opening avenues to the inmost self through the arrangement of light and shadow on the surfaces of the human body. They want to explode into motion. In short order, they would.

Our online encounters during the pandemic could use a dose of Sarony’s art – some fun backdrops, better costumes and lighting, a healthy dollop of self-deprecating humor (Room Rater on Twitter agrees with me). Our Zoom lives are stiff as cartes de visite and, at the same time, close to the animated photos in the Harry Potter books and movies, depicting awkward, anxious, halting moments in over- and underlit loops. Put that way, come to think of it, they will have something quite profound to say about our times. So save those screenshots and videos. Posterity will thank you for it, though your relatives and colleagues may not.

The Amon Carter Museum of American Art is at 3501 Camp Bowie Blvd. For more information, www.cartermuseum.org or 817-738-1933.

![“[Painter]” by unknown photographer, 1890s. Albumen silver print. William L. Schaeffer Collection.](https://www.antiquesandthearts.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/unknown_photographer_[painter]_1890s_albumen_silver_print_william_l._schaeffer_collection-673x1024.jpg)

_amon_carter_museum_of_american_art_fort_worth_texas_p1976.jpg)