Chris Cornelius, a member of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin and chair of the University of New Mexico’s School of Architecture and Planning, referenced Indigenous cosmology in a new gallery at the Milwaukee Art Museum housing selections from Chipstone’s growing collection of contemporary Native American ceramics. The debut presentation in the space, “Knowledge Beings,” features 13 works by 13 artists. Center is the clay installation “Totems” by Nora Naranjo Morse (Kha’p’o Owingeh/Santa Clara Pueblo). Jon Prown photo.

By Laura Beach

MILWAUKEE, WIS. — Jonathan Prown, executive director and chief curator of the Chipstone Foundation, recalls a time around 20 years ago when a New York Times reporter remarked that Prown and former Chipstone curator Glenn Adamson thought “outside the box.” The colleagues looked at each other and said, “What box?”

Not much has changed. Impatient with shopworn approaches to the study of American material culture, Prown, who took up his post in suburban Milwaukee in 1999, has been consistent in his vision for the foundation, which administers the former home and collection of the late Stanley and Polly Stone. “In today’s museum world, it is essential for many reasons to explore increasingly innovative and expansive approaches to interpretation and display,” says Prown, steward of an institutional brand admired for its fierce intellectuality, rigorous standards and novel approaches.

In recognition of its achievement over the past three decades, the Antiques Dealers Association of America (ADA) is honoring Chipstone Foundation with its Award of Merit, to be presented at a dinner at the Delaware Antiques Show on November 11. The prize acknowledges Chipstone’s accomplishment across a range of educational endeavors and honors the people most responsible for its success. Along with Prown, they include two longtime friends: Luke Beckerdite, Chipstone’s executive director between 1990 and 1999 and the founding editor of its annual journal American Furniture; and Robert Hunter, founding editor of the annual volume Ceramics in America. Glenn Adamson, who left Chipstone in 2005 for a series of high-profile undertakings and is perhaps the closest thing the decorative arts field has to a public intellectual, edits Chipstone’s new online quarterly Material Intelligence, launched in 2021.

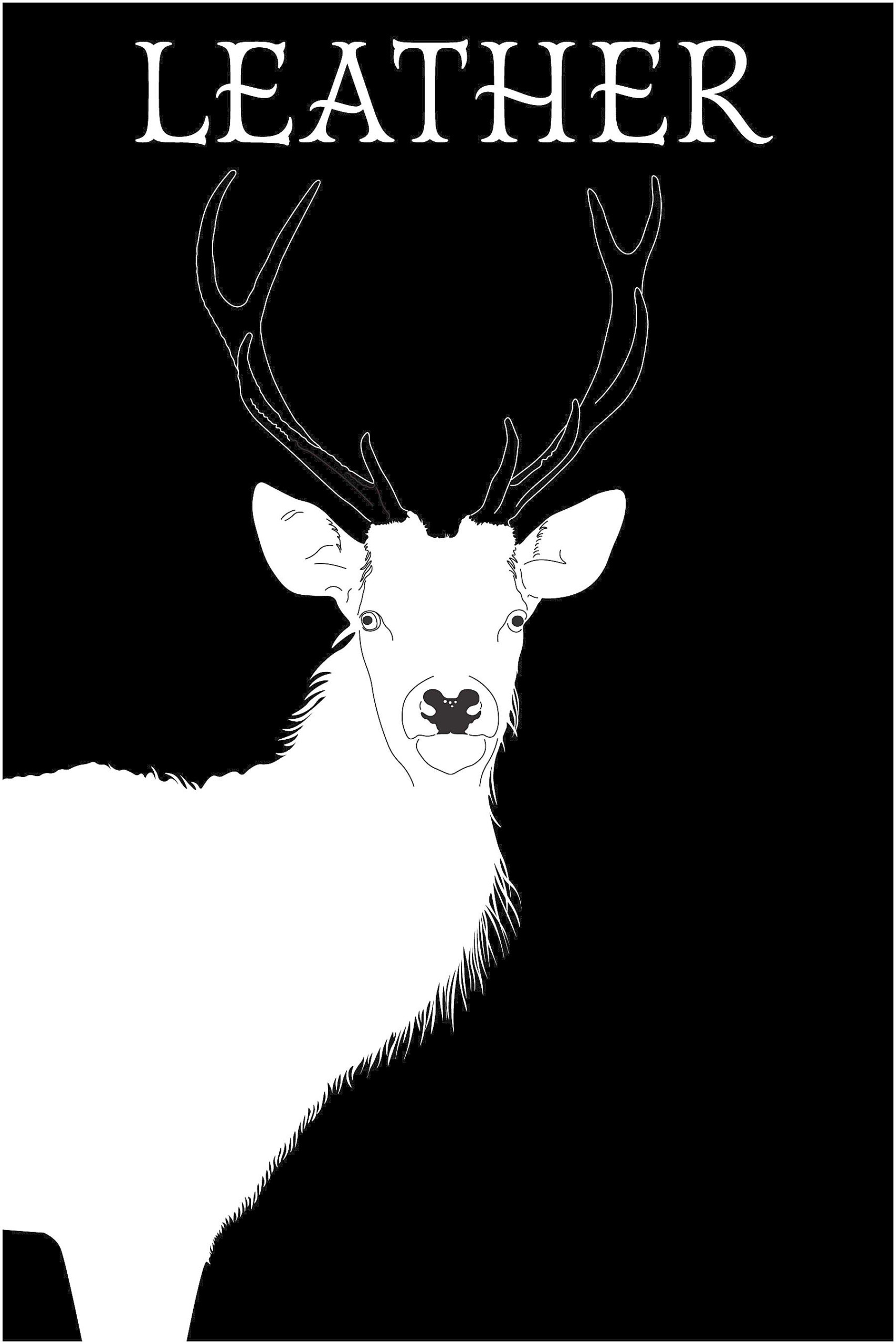

Former Chipstone curator Glenn Adamson edits the foundation’s new online quarterly Material Intelligence, launched in 2021 and enlivened by Wynne Patterson’s lithe illustrations. Articles in the current edition, “Leather,” range from an exploration of the Indigenous origins of Russia leather to an essay on leather’s edgy allure by Deborah Landis, costume designer for Michael Jackson’s 1983 Thriller video.

The Chipstone sensibility lingers in a small but influential group of former foundation curators and fellows, among them Ethan Lasser, chair, and Nonie Gadsden, curator, in the Art of the Americas department at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. Rose Camara, Chipstone’s current Charles Hummel curatorial fellow, is an artist and art historian who trained at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Courtauld Institute. Former Chipstone curator Ruthie Dibble recently joined the Peabody Essex Museum as curator of American decorative art.

Chipstone evolved in response to its limitations. Far from the cultural riches of New York or the curatorial training grounds of Winterthur, the foundation made its way by building alliances, a collaborative approach suited to an increasingly mobile, decentralized world. Chipstone’s principal partnerships have been with the Milwaukee Art Museum, where portions of its collections have been on view since 2001 and where the foundation has mounted more than 50 thoughtful exhibitions, and with the University of Wisconsin at Madison, where the Stone fortune underwrote a chaired position, held by Ann Smart Martin before her retirement, for the study of American decorative arts and material culture, and now supports Sarah Anne Carter’s position as executive director of the Center for Design and Material Culture at UW.

Well before Black Lives Matter helped open eyes to longstanding inequities in America’s museums, Chipstone explored expressions of race in the decorative arts in a sequence of exhibitions beginning in 2005 with “About Face: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the African-American Image.” In 2010, it mounted “To Speculate Darkly: Theaster Gates and Dave the Potter.” The show contributed to the growing prominence of both Gates, a contemporary Chicago-based artist, and the formerly enslaved potter David Drake, whose inscribed vessels are now part of the American canon. Funded by Chipstone and the Wunsch Americana Foundation, a 2016 think tank at the Metropolitan Museum of Art set the stage for “Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina.” Co-curated by Lasser, the major traveling exhibition opened at the Met in 2022 before embarking on its current tour.

The 2010 Chipstone exhibition “To Speculate Darkly: Theaster Gates and Dave The Potter” contributed to the growing prominence of Gates, a contemporary Chicago-based artist, and the formerly enslaved potter David Drake. Installation view, Milwaukee Art Gallery. Jim Wildeman photo.

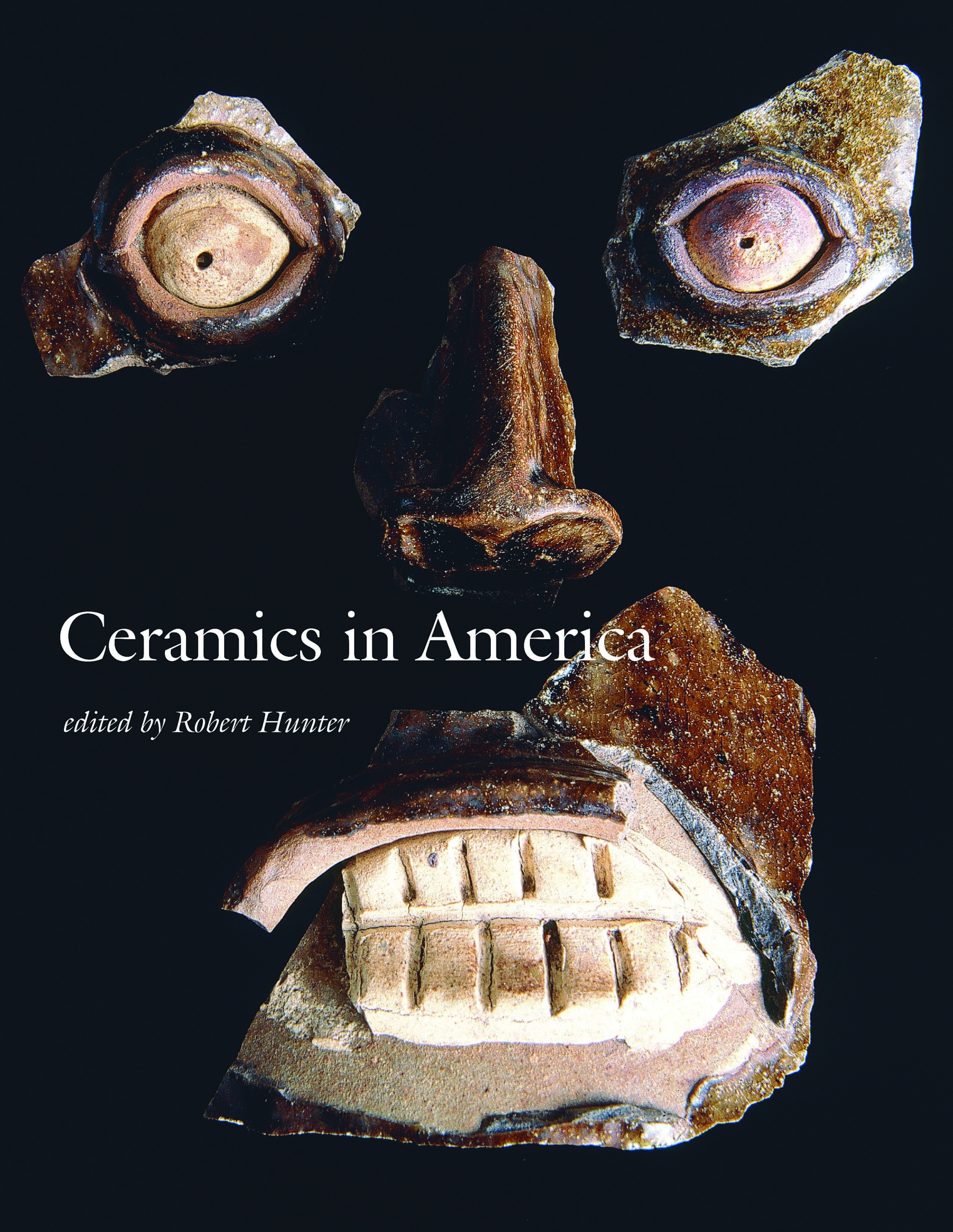

Related content on race appeared even earlier in Ceramics in America. “If I had to pick one article in this area in 22 years, it would be Sam Margolin’s 2002 piece on antislavery ceramics made between 1787 and 1865,” says Hunter, who acknowledges, “Multiple articles on Drake and, more broadly, face jugs in Ceramics in America have helped scholars build to the next step.”

Chipstone initiatives have changed the collecting landscape. One thinks, for instance, of the suite of articles in Ceramics in America 2007 on John Bartlam, the South Carolinian now credited with producing the first commercially successful soft-paste porcelain in America, circa 1765. With a fearlessness that at the time shocked some in the antiques community, Beckerdite and co-author Alan Miller exposed fakes in Chipstone’s collection in a widely discussed article for American Furniture 2002 and in an exhibition at the Milwaukee Art Museum. The foundation also helped underwrite Southern Furniture, 1680-1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection (1997) by Prown and Ronald L. Hurst. The book served as the catalog to an exhibition of similar name and coincided with the Southern-themed American Furniture 1997. The research, the most sustained on the topic in 50 years, heralded new interest among dealers and collectors in the decorative arts of the South.

Led by Beckerdite, Chipstone’s multi-year project documenting North Carolina earthenware by Moravians and other Piedmont makers was a model of cross-disciplinary research joining new scholarship in art, history, archaeology and religion. Research for the 2009 and 2010 editions of Ceramics in America provided the foundation for “Art in Clay: Masterworks of North Carolina Earthenware,” the traveling exhibition organized jointly by Chipstone, Old Salem Museums and Gardens, and Caxambas Foundation.

Luke Beckerdite, left, converses with London dealer Garry Atkins, center, at the New York Ceramics Fair in 2008. Rob Hunter is right. Beckerdite and Hunter continue to advise collectors.

Beckerdite recalls, “Our original intent was to publish one volume that updated John Bivins’ The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (1972), but it quickly became apparent that much more was needed. What was thought to be one school of pottery was actually several schools represented by potters with different social, cultural and religious backgrounds; and that each of those schools was more complex than previously thought. Thankfully, nearly all the resources we needed to access were in close proximity — the Moravian archives, archaeological and decorative arts collections at Old Salem and Bethabara, regional sites like Mount Shepherd and the Dennis potteries, and private collections — as were the scholars involved.”

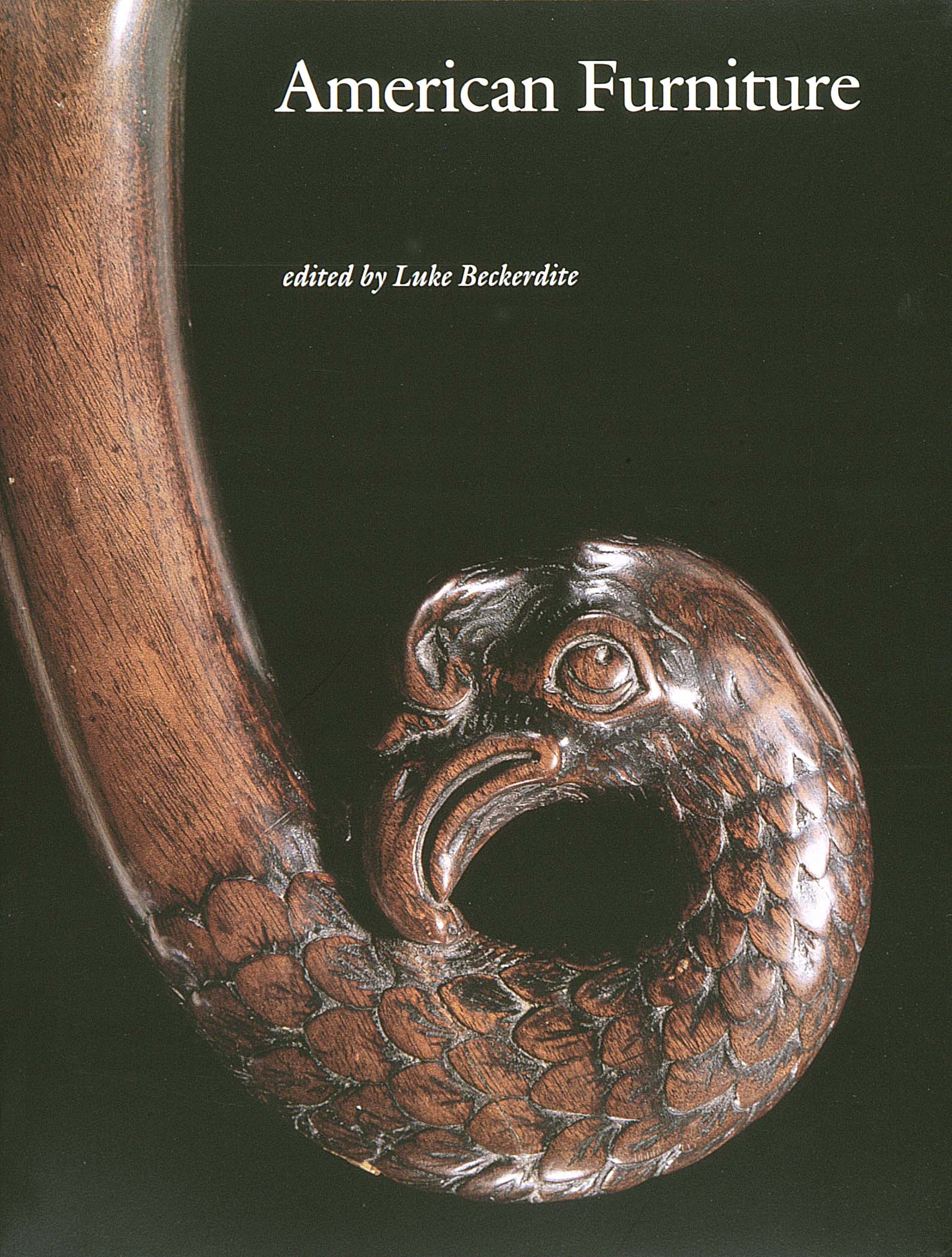

American Furniture and Ceramics in America are essential reading in their subject areas. Their handsome appearance, as well as that of Material Intelligence, reflects the sustained contributions of art director Wynne Patterson and, in the case of the first two publications, the photography of Gavin Ashworth. Beckerdite, who entered the museum field in 1979 and pioneered American Furniture in 1993, recently put his stamp on his 30th and final volume, his first co-edited with his successor, Martha Willoughby. In American Furniture’s debut edition, he wrote of his vision for the publication as a forum for cutting-edge research and interdisciplinary studies. Changes in the journal over time reflect evolution in the field itself, he now says, noting, “Many of the new discoveries and much of the leading research that has emerged over the last 20 years has come from independent scholars, conservators, dealers and auction professionals.”

Hunter, whose interests and experience encompass archaeology, history, technology and the marketplace, has likewise sought to make Ceramics in America a meeting place for diverse expertise, a project in which he is frequently assisted by his partner, Michelle Erickson, a contemporary ceramicist with an unparalleled understanding of historical ceramics technology. Priding himself on presenting research that otherwise might go unpublished, Hunter has given voice to members of the trade — notably Gary and Diana Stradling, Marshall Goodman, Jonathan Horne, Roderick Jellicoe, Garth Clark, Sumpter Priddy, Lorraine German, Jill Fenichell, Joy Hanes and Brandt, Mark and Luke Zipp — and collectors, from “true antiquarians” Jonathan Rickard and Donald Carpentier to Arthur Goldberg, Robert Teitelman, Joseph P. Gromacki and Bruce Coleman Perkins.

Robert Hunter launched the Chipstone journal Ceramics in America in 2001. With the Virginian here are two mid-Nineteenth Century alkaline-glazed stoneware vessels. The 20-gallon jar, left, is from Edgefield, S.C. Right, a 16-gallon jar by Daniel Seagle of Catawba Valley, N.C.

Hunter echoes the enthusiasms of the late historical archeologist and frequent journal contributor Ivor Noël Hume, who wrote in Ceramics in America 2014, “archaeology is less about finding than finding out.” He is proud of the journal’s illustrated technology articles — “a true collaboration among craftspeople, photographers, designers and scholars” — and believes the journal’s most substantive accomplishment may be its focused articles on the stoneware of Boston, New York, Baltimore, Richmond and Alexandria.

For the past three years, Hunter has co-edited Ceramics in America with Ronald W. Fuchs II, to whom he is passing, as he puts it, “the ceramic baton” after 2024. Fuchs, a ceramics curator who held posts at the Reeves Museum and Winterthur, and his American Furniture counterpart, Willoughby, a consulting specialist at Christie’s, communicate regularly with Hunter and Beckerdite as well as with each other as they plan future volumes.

Willoughby says, “These journals were started 30 and 20 years ago and the field is taking a new direction. Fewer scholars are engaged in traditional furniture studies. It can be challenging to tell the stories of overlooked Americans in the context of furniture and ceramics, but good work is being done. I’m always looking for objects or ways of looking at objects that tell a bigger story.” An issue devoted to women as makers, patrons and consumers is under discussion.

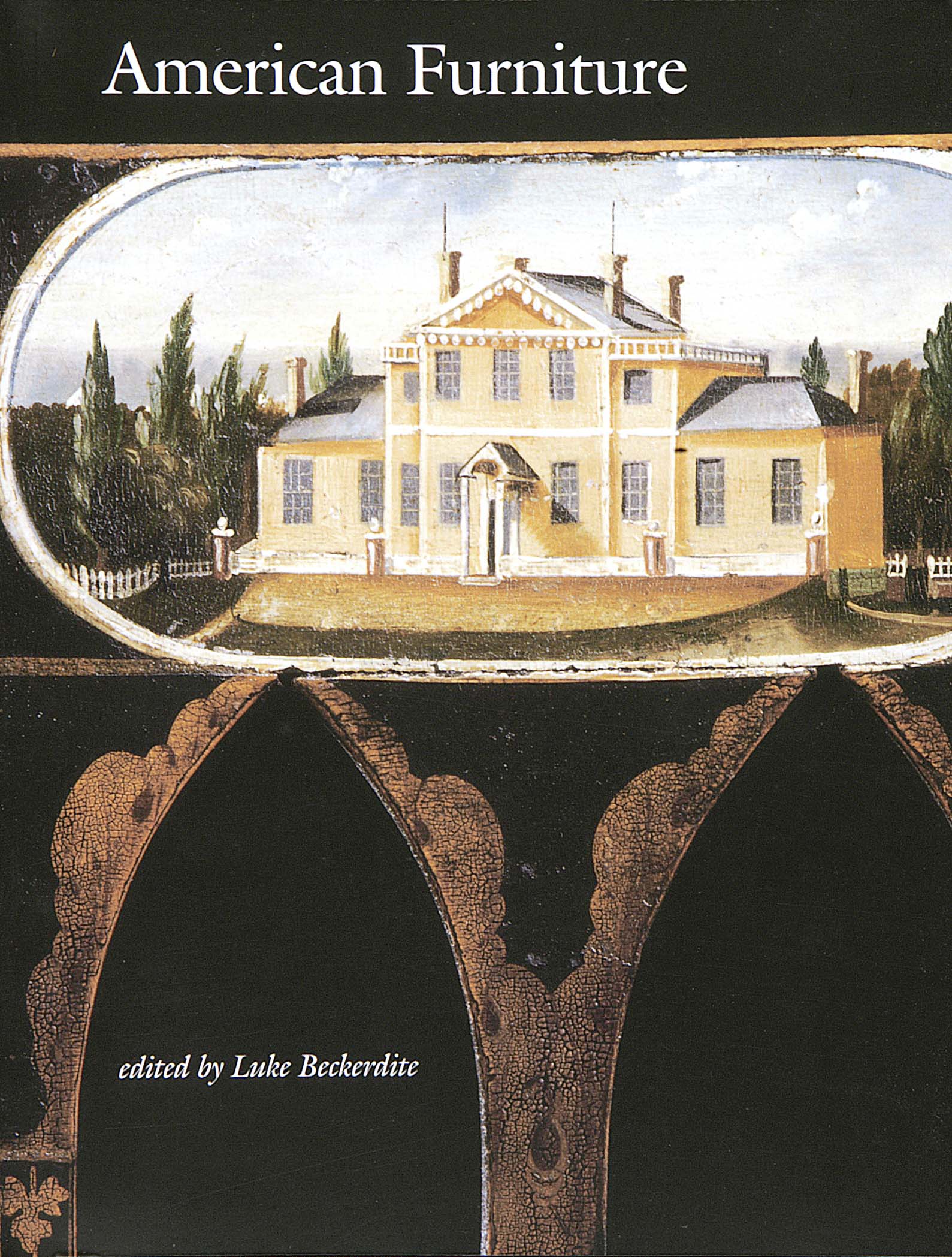

In American Furniture’s debut edition in 1993, Luke Beckerdite wrote of his vision for the publication as a forum for cutting-edge research and interdisciplinary studies.

Amplifying his colleague’s response, Fuchs says, “Ceramics in America has a wonderful author pool of archeologists, curators, independent scholars and collectors who are doing amazing work, but I would like to continue to broaden that pool to find new authors as well as new audiences.” Fuchs, who like Hunter has a background in archaeology, anticipates a continuing emphasis on excavated ceramics in Ceramics in America as well as articles on ceramics in domestic settings, and perhaps more on Asian export wares, his own expertise. He reveals, “One of the things I like most about the journal is the variety of topics I get to work on. For 2025, I am working on several interesting articles, including one on hong bowls, one on tea wares and one on George Ohr.”

Beckerdite and Hunter look forward to more time for research. Beckerdite has an article slated for American Furniture 2024, plus two more in the works. A “dealer at heart,” he will continue advising collectors. Hunter’s latest article, in Ceramics in America 2023, is “Southern Hoodoo and the Dr Peter Davis Ring Bottle.” A social media maven, Hunter first learned of the inscribed and dated vessel via a Facebook message in 2017. Hunter has other articles lined up; is working on a book on English shell-edged earthenware, a longstanding interest; and advises several prominent collectors, among them William C. and Susan S. Mariner, benefactors of a gallery, guest curated by Hunter, of antebellum Southern pottery at the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts in Winston-Salem, N.C.

Chipstone treats its gallery spaces at the Milwaukee Art Museum as a laboratory for exploring innovative approaches to display and interpretation. Ruthie Dibble recently collaborated with Tiffany Momon, an assistant professor at Sewanee, on “Troubled Like the Restless Sea.” The show, whose title quotes abolitionist Frederick Douglass, confronts the paradox of material splendor financed by morally repugnant means.

Chipstone’s growing collection of contemporary Native American ceramics complements its existing holdings of wares used in America. Added to the collection in 2021 is “Totems” by Nora Naranjo Morse (Kha’p’o Owingeh/Santa Clara Pueblo, b 1953) of 2005-18. Hand-coiled Kha’p’o and micaceous clay tempered with volcanic ash, with acrylic paint, natural clay slip, Bondo and other adhesives and mesh tape. Gavin Ashworth photo.

“Knowledge Beings,” an immersive gallery showcasing Chipstone’s recent decision to collect contemporary Native American ceramics, uses bold design to engage and inform. The foundation worked with architect Chris Cornelius — an enrolled member of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin, chair of the school of architecture and planning at the University of New Mexico, and founding principal of studio:indigenous — to create a gallery in the round invoking elements of the spiritual heritage of the included artists, who represent a swath of Native North America.

Chipstone’s outsized influence on the field of American decorative arts over the past three decades belies its small staff and minimal bureaucracy. The foundation has leveraged its resources to bring dealers, collectors, curators, amateur scholars and the public together in lively, sometimes unexpected ways. As Prown says, “What gets studied and how it gets studied changes with each passing year for our team and our collaborators. Indeed, we draw a great deal of energy from our unique institutional ability to be programmatically nimble and move in unexpected directions. What remains constant, however, is the deep commitment to doing engaging and thought-provoking scholarship that strives to expand the parameters of the American decorative arts field.”

About The ADA Award of Merit Dinner

The ADA Award of Merit dinner is planned for Saturday, November 11, from 6 to 8 pm in conjunction with the Delaware Antiques Show in the Christina Ballroom, Chase Center on the Riverfront, 815 Justison Street, Wilmington, Del. For information or to purchase tickets, visit www.adadealers.com.

A Chipstone Reader

By Laura Beach

WILLIAMSBURG, VA. — With roughly 70 volumes of Ceramics in America, American Furniture and now Material Intelligence in circulation, the scholarship emanating from Chipstone defies facile analysis. In the spirit of diversity, we asked readers to name their favorite articles or volumes. Their answers, organized chronologically, follow.

“Every article has been so useful in its own way. From ‘Roman Gusto in New England: An Eighteenth-Century Boston Furniture Designer and His Shop’ by Alan Miller (American Furniture 1993) to ‘Forging the ‘Real War’: Nostalgia, Memory, and Trauma in the Bingham Memorial Secretary” by Brandy Culp and Ruthie Dibble (American Furniture 2022), there is an amazing breadth of indispensable information for collectors, scholars, historians, artisans, curators, genealogists, scientists, professors and students.” —Erik K. Gronning, senior vice president, senior specialist and head of Americana Department, Sotheby’s New York

“Two volumes that seem to always come up in collector searches are American Furniture 1993, which was the debut issue, and the Rhode Island-focused American Furniture 1999. As a decorative arts scholar myself, the 1993 volume continues to impress as a Who’s Who of articles by experts in the field. As a book dealer, I can say that once American Furniture caught on, the 1993 volume became hard to find. The 1999 volume is a darling for collectors. Newport craftsmanship continues to be at the apex of American material culture. The volume satisfies a deep-seated need to understand the Newport aesthetic and see it from many angles.” —Judith Livingston Loto, ADA executive director and owner, Russack & Loto Books, Northwood, N.H.

“An article we have returned to quite often in American Furniture is Robert A. Leath’s 1994 study ‘Jean Berger’s Design Book: Huguenot Tradesmen and the Dissemination of French Baroque Style.’ In almost a side note to the main point of the article, it contains the most complete reference we have found on the English painter J. Cooper’s brief sojourn working in Boston in the early years of the Eighteenth Century. We have been lucky enough to own half a dozen of his paintings — some signed, some not — and are very grateful for Mr Leath’s article placing this hitherto mysterious artist squarely in Boston. Just an example of how fruitful a small seed of scholarship can be in these volumes. The Chipstone publications have been an immeasurable resource for all interested in the areas of furniture and ceramics.” —Grace and Elliott Snyder, South Egremont, Mass.

“Many articles put pieces of the furniture history puzzle together (or in close proximity), but for a single article I would name Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s ‘Furniture as Social History: Gender, Property and Memory in the Decorative Arts’ in American Furniture 1995. This article demonstrates the power of broad awareness and reading of history and historical references on the one hand, and on the other, it provides avenues of interest for many. I have used it many times for audiences who are not armed with lights, magnifying glasses and other accoutrements for furniture nitpicking.” —Philip D. Zimmerman, museum and decorative arts consultant, Lancaster, Penn.

“I am sure others came up with the ‘sexy highboy’ article by Jonathan Prown and Richard Miller (‘The Rococo, the Grotto, and the Philadelphia High Chest,’ American Furniture 1996), but I have three favorites for their thoroughness and cutting-edge information. In ‘Immigrant Carvers and the Development of the Rococo Style in New York, 1750-1770’ (American Furniture 1996), Luke Beckerdite shows a number of magnificent carved interiors and connects them to decorative carving on furniture. Another contender is Nancy Goyne Evans’ two-part article in American Furniture 2007 and 2008, ‘The Written Evidence of Furniture Repairs and Alterations, How Original is ‘All Original.’ A recent favorite is ‘The Documented Chairs of William Savery’ by Philip D. Zimmerman in American Furniture 2022. His study is a blueprint of how object-based studies should be done.” —Frank Levy, Bernard & S. Dean Levy, Inc., New York City

“American Furniture was already revered as a source of excellent information when I started with Liverant Antiques in 1998. I remember researching an early leather-back chair with a carved crest and carved front stretcher. It was a remarkable chair, so bold and sophisticated, in a way so European, but somehow different. I came across the article ‘Hidden in Plain Sight: Disappearance and Material Life in Colonial New York’ by Neil D. Kamil in American Furniture 1995. Wow! What I found was not only a plethora of information about the chair but a whole new way of looking at antiques, economy and diversity. The article blew up the simplified notions I had about regionalism and culture in early America. I remain astounded by the vast quantity of information held in these journals. They are an essential part of my research and career in American antiques.” —Kevin J. Tulimieri, Nathan Liverant and Son Antiques, Colchester, Conn.

N.B.: Proprietor Arthur Liverant says that when Dr Kamil, now an associate professor of history at the University of Texas at Austin, first wandered into Liverant Antiques roughly 30 years ago, Zeke Liverant was skeptical of the informally dressed young man. Kamil’s depth of knowledge soon became apparent. Arthur says, ‘Zeke asked Kamil to sit down, and they spoke for a couple of hours, easily. It was the start of a great friendship.’”

“My favorite issue of Ceramics in America was the very first one in 2001. It was exciting to witness this collection of scholarship in an area that I so love. Most of the articles were written by people I knew — among them Donald Carpentier, Jonathan Rickard and Diana and J. Garrison Stradling — which took it beyond the lessons learned to the personal. And although the focus was America, most of the articles were about the use in this country of articles manufactured in Great Britain. The quality of scholarship and the new information has continued through the years, but, as they say, the first time was the best!” —Joy Hanes, Hanes & Ruskin Antiques, Niantic, Conn.

“‘A Table’s Tale: Craft, Art, and Opportunity in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia’ by Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller (American Furniture 2004) is my go-to article when I am looking at carving I think might be by Martin Jugiez and Nicholas Barnard. It is just so thorough and clearly adept at identifying those particular makers and their scope of work.” —Martha Willoughby, editor, American Furniture

“We would single out ‘Beneath his Magic Touch: The Dated Vessels of the African-American Slave Potter Dave’ by Arthur F. Goldberg and James Witkowski (Ceramics in America 2006). This was such a forward-thinking, important article that came well before today’s intense general interest in African-American potters. While new discoveries are still being made, their catalog of all known Dave vessels is an immensely important resource that is still routinely consulted, giving an excellent representation of when Dave’s most active periods were and style trends. As David Drake has really assumed the role as the most prominent period American utilitarian potter, it is difficult to overstate the importance of that article.” —Luke and Brandt Zipp, Crocker Farm, Inc., Sparks, Md.

“Ceramics in America 2007 holds a special place, both because it served as the catalog of sorts for my 2008 exhibition ‘Colonial Philadelphia Porcelain: The Art of Bonnin and Morris’ and as homage to collector George M. Kaufman. The exhibition surprised many when it was a sleeper of a success and, tragically, closed on the day that our director Anne d’Harnoncourt died unexpectedly. The volume is a fulcrum of sorts: seminal articles were written before and after it, and all contribute to the corpus on Bonnin and Morris’ venture in Philadelphia. Now, for Philadelphia’s Tucker porcelain of the 1820s and 1830s. I have been slowly plugging along at it and am looking forward to overseeing that one myself.” —Alexandra Kirtley, curator of American decorative arts, Philadelphia Museum of Art

“Two issues resound: Ceramics in America 2007, which reorganized dates of American porcelain production, with articles by Robert Hunter, Roderick Jellicoe, Graham Hood and Michael Brown, and Ceramics in America 2019, which featured ‘The Search for the Green‑Glaze Potter of Philadelphia’ by Deborah Miller. Her observations on David Seixas of New York confirmed what American potters could do.” —Jill Fenichell, appraiser and ceramic specialist, El Cerrito, Calif.

“There are many good articles, but my favorite volumes are Ceramics in America 2009 and 2010, emphasizing Moravian and related pottery in North Carolina.” —Sam Herrup, Samuel Herrup Antiques, Sheffield, Mass.

“When I was working at Washington and Lee as curator of the Reeves Collection and teaching in the art history department, ‘The Chinese Scholar Pattern: Style, Merchant Identity, and the English Imagination’ by Sarah Fayen Scarlett in Ceramics in America 2011 was one of my required readings. It perfectly distills the cultural connections and exchange that came about because of the global trade in Chinese porcelain. It is a well-written, deep dive into many of the different perspectives on this one design.” —Ronald W. Fuchs II, editor, Ceramics in America

“Most memorable articles? That would be a long list, but one that immediately comes to mind is Steve Brown and Will Neptune’s article ‘Classical Proportioning in Eighteenth-Century Furniture Design’ (American Furniture 2017). The authors, whom I knew as furniture makers but had never met, contacted me and said, ‘We’ve been researching classical proportioning and would like to share our findings the next time you’re in the Boston area.’ A few months later, I met them at the North Bennet Street School expecting to see more of the same general application of classical proportioning observed by previous scholars. Instead, they demonstrated that in the work of some cabinetmakers — Eliphalet Chapin being one — classical proportioning and geometric construction was present in every aspect of design. That represented a quantum leap in scholarship.” —Luke Beckerdite, editor, American Furniture

“As a furniture historian, my appreciation for American Furniture goes without saying. But as a failed archaeologist, I am particularly fond of the attention Rob has paid to the impact of fieldwork on ceramics history through the pages of Ceramics in America. The 2017 issue, co-edited with Colonial Williamsburg’s Angelika Kuettner and devoted to the impact of urban excavations in locations ranging from Massachusetts to Florida to Louisiana, was particularly impressive. The essays represent a brilliant compilation of the cultural influences that synthesized within these diverse and dynamic communities. The alumni community founded by former Chipstone Foundation curators is a force to be reckoned with, and we look forward to the contributions of the group’s latest addition, Ruthie Dibble, as she joins the curatorial team at the Peabody Essex Museum.” —Matthew A. Thurlow, executive director, The Decorative Arts Trust