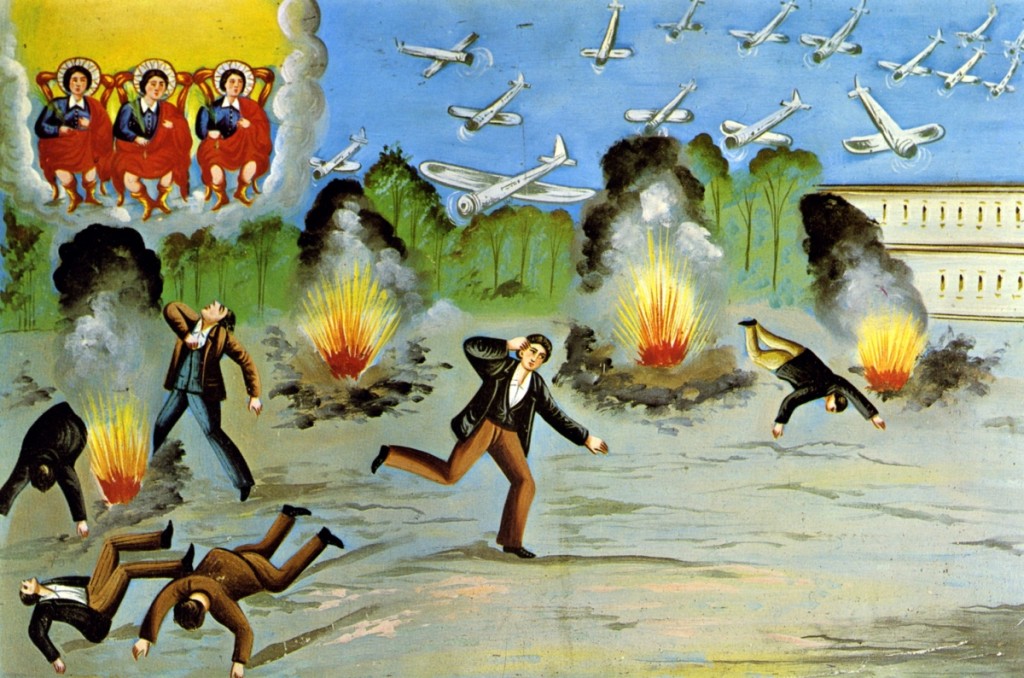

Retablo of Josefina Rivera for safety in a bus accident, Mexico, 1954. Tempera on tin. Durand-Arias Collection.

By Kate Eagen Johnson

NEW YORK CITY – What if makers were not the most important figures in an arts exhibition? Challenging conventional subject matter and standard curatorial method is “Agents of Faith: Votive Objects Across Time and Place,” on view at New York’s Bard Graduate Center (BGC) Gallery through January 6. In this affecting exploration of the universal, yet highly personal activity of making ritual offerings, attention has shifted to givers and to receivers, the latter including deities, saints and the departed. As Bard Graduate Center associate professor Ittai Weinryb stated, “This is a conceptual exhibition…across religions, cultures, societies and periods. [It shows] the ways in which people charge objects with meanings.”

A medievalist-by-training, Dr Weinryb conceived of the presentation and has curated it with Bard Graduate Center Gallery chief curator Marianne Lamonaca and associate curator Caroline Hannah. They have gathered more than 250 objects spanning three and one-half millennia for this inaugural exhibition on the topic, part of a celebratory series of exhibitions and lectures marking the 25th anniversary of the founding of the Bard Graduate Center which will run through the year 2020. As such, it is a fitting tribute to the research institute’s trailblazing, iconoclastic approach and commitment to documenting the unfairly overlooked and explaining the difficult within the decorative arts, design and material culture sphere.

In “Agents of Faith,” Weinryb, Lamonaca and Hannah examine humans’ collective desire to connect with the spiritual world through ceremonial donation of art, artifacts, money and other goods. This global survey covers traditions that transcend culture as well as more culturally specific expressions. The former includes the communal placement of symbolic objects at sites considered sacred or associated with tragedy as well as the proffering of objects, flowers, food and drink to holy ones and to the deceased.

Weinryb underscored that the practice of votive giving “transcends historical distance.” He discussed how individuals in the ancient world, in Nineteenth Century Germany, and in the United States during the 1990s all took part in this activity and that the objects seen here reveal their memories, anxieties, hopes and dreams. In keeping with the spirit of continuity, visitors are invited to add their own requests to Yoko Ono’s “Wish Tree” as installed in the exhibition.

Over the centuries, some supplicants crafted their own offerings, while others patronized artists and artisans producing ex-votos for a living. These votives were singular orders or mass-produced, created domestically or plundered from distant locales, artfully or less skillfully wrought from expensive or humble materials. Art-and-artifact communiques and surrogates often depicted, or in some other way referenced, what was desired, what had been granted, who was beseeched or who was remembered.

Suggestive of the range of objects shown on the three floors of the BGC Gallery are an Etruscan votive male bust of clay from the Third to Second Century BCE, a miniature stupa reliquary of schist carved during the Second or Third Century in the ancient region of Gandhara of present-day Pakistan, a Nineteenth Century wooden ship model dedicated to the Madonna del Sococoro from the island of Ischia near Naples, and a Mexican tempera on tin retablo commemorating a woman’s miraculous survival of a bus accident in 1954.

Weinryb talked about objects to which he was particularly drawn. Turning to a beautifully rendered sculpture of an animal leg, Weinryb shared that its story begins with a donkey in Sardinia in the year 1951. The donkey had a problem with its leg, which over time healed. In gratitude for the donkey’s return to wellness, its owner painstakingly carved a replica of the limb as an offering to the Madonna del Rimedio. To identify the very donkey restored to health, the man fastened an annotated photograph to the sculpture. Weinryb considers the charming piece representative of “the labor of love invested in each and every one of these objects.”

An object evoking emotion of a different sort is a plastic figurine of the dog “Lassie” left at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 1993. Weinryb told how Ian J. Franks, who was killed in action in 1968, had fashioned the collie toy as a child. His relatives penned and attached the following inscription. “Built + painted by a 12 year old boy, who died a 21 year old man March 23rd 1968 / Ian J. Franks / Love, Mom Dad Ron Andy + Our families you never met.” Weinryb characterized its power as “punching you in the stomach, … so heartbreaking, so strong” and underscored how it captures “the cycle of life of one human being in a single object.”

It comes as no surprise that Weinryb and his colleagues mined out-of-the-ordinary public and private holdings to realize their exceptional exhibition. Among these repositories are the Vietnam Veterans Memorial collection and the Rudolf Kriss collection of folk art at the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum (Bavarian National Museum), Munich.

Soon after the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC was dedicated on November 13, 1982, visitors spontaneously began to lay symbolic objects at “The Wall.” The National Park Service has saved and archived more than 400,000 items, 44 of which are on view in “Agents of Faith.” These emblems of remembrance and sorrow include a model of a United States Navy river patrol boat, a San Miguel Pale Pilsen beer bottle containing a letter addressed to a deceased comrade and the “Hero Bike,” a customized Police Special motorcycle honoring the 37 missing-in-action servicemen from Harley-Davidson’s home state of Wisconsin.

Votives are frequently personalized so that the identities of those involved are made clear. Its inscription in Italian can be translated as “Miracle granted to Cavallaro Guiseppe da Pedara on December 17, 1944 (Catania).” Votive painting of Cav. Giuseppe of Pedara for protection during an aerial bombing offered to Saints Alfio, Filadelfo and Cirino, Sicily, 1944. Oil on metal. Rudolf Kriss collection, Asbach Monastery, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Munich. ©Bayerisches Nationalmuseum Munich.

—Walter Haberland photo

Asked about the origins of the Kriss collection, Weinryb related how the ethnographer Rudolph Kriss (1903-73) began to acquire devotional objects from the Tirol area of Austria and Germany and elsewhere about 1920. Among the featured objects from this underappreciated resource are a lungs votive, molded in wax and then hand decorated; a forged iron figure of yoked oxen deposited in an Austrian church dedicated to a saint associated with iron; and a painting commissioned in appreciation for divine protection during the aerial bombing of Sicily in World War II. Noting the public’s very limited access to both the Vietnam Veterans Memorial collection and the Kriss collection, Weinryb observed, “This is a unique moment to see these objects on display.”

Other remarkable but rarely exhibited works make an appearance. Weinryb highlighted a late Seventeenth or early Eighteenth Century Armenian Gospel lent by the Morgan Library and Museum. The precious volume is “treasure bound” with Seljuk coins; seal stones with writing in Arabic, Armenian and Greek; and a gilt-metal cross among other significant ornaments. Also noteworthy is a mid-Fourteenth Century Italian Madonna and Child on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. X-ray analysis reveals that a rosary, a piece of lace and other objects rest within the polychrome wooden sculpture. These inserts are likely votives.

Edited by Weinryb, the 372-page accompanying catalog contains 17 essays and abundant illustrations. In it, scholars address such diverse themes as the interconnectedness of African art forms and community belief systems, the roles votives play within German pilgrimage culture and votive giving in Islamic societies.

While there is much to rouse the intellect in this project integrating aspects of history, anthropology, sociology, religious studies, art history, archaeology and material culture analysis, the emotions are also kindled. By its nature, the subject of votive giving encourages empathy and reflection. Those seeking respite from the hustle and bustle of Manhattan during the holiday season know right where to find manifestations of love and gratitude worthy of contemplation.

The Bard Graduate Center Gallery is at 18 West 86th Street. For information, 212-501-3000 or bgc.bard.edu.

Ittai Weinryb served as the editor of the catalog published by Yale University Press in collaboration with Bard Graduate Center.

.jpg)