Albert York’s auction record now stands at $239,400 with “Still Life: Green Apples,” a 20-by-22-inch oil on canvas. “It struck me as a little more conventional, less like his others,” Alasdair Nichol, chairman at Freeman’s, said. “He was known for doing pastoral scenes and still lifes. I hadn’t seen anything like this, but there was no question it was a very appealing painting.” Nichol said it sold to a Philadelphia collector.

Review by Greg Smith, Photos Courtesy Freeman’s

PHILADELPHIA – Outside the confines of the artist’s lifetime representative, Davis Galleries, which would later rename to Davis & Langdale Company, not many sellers have handled works by Albert York (1928-2009). His secondary market records are as scant as his museum shows, but that does nothing to slow a feverish market for this obscure American master. Supply is low, demand is high.

The elusive artist’s only public photograph in The New York Times depicts him looking away from the camera, as if the photographer asked him to pose and he replied, “no thanks.” Any profile on the artist calls attention to his self-effacing personality.

After returning from the Korean War, York settled in New York City with aspirations to study art, though he eventually abandoned formal education due to the cost. He began working as a gilder in Robert Kulicke’s frame shop. It was a full decade working there before York revealed his talent as an artist to Kulicke, who quickly made an introduction to Roy Davis of Davis Galleries. Davis would represent York his entire life.

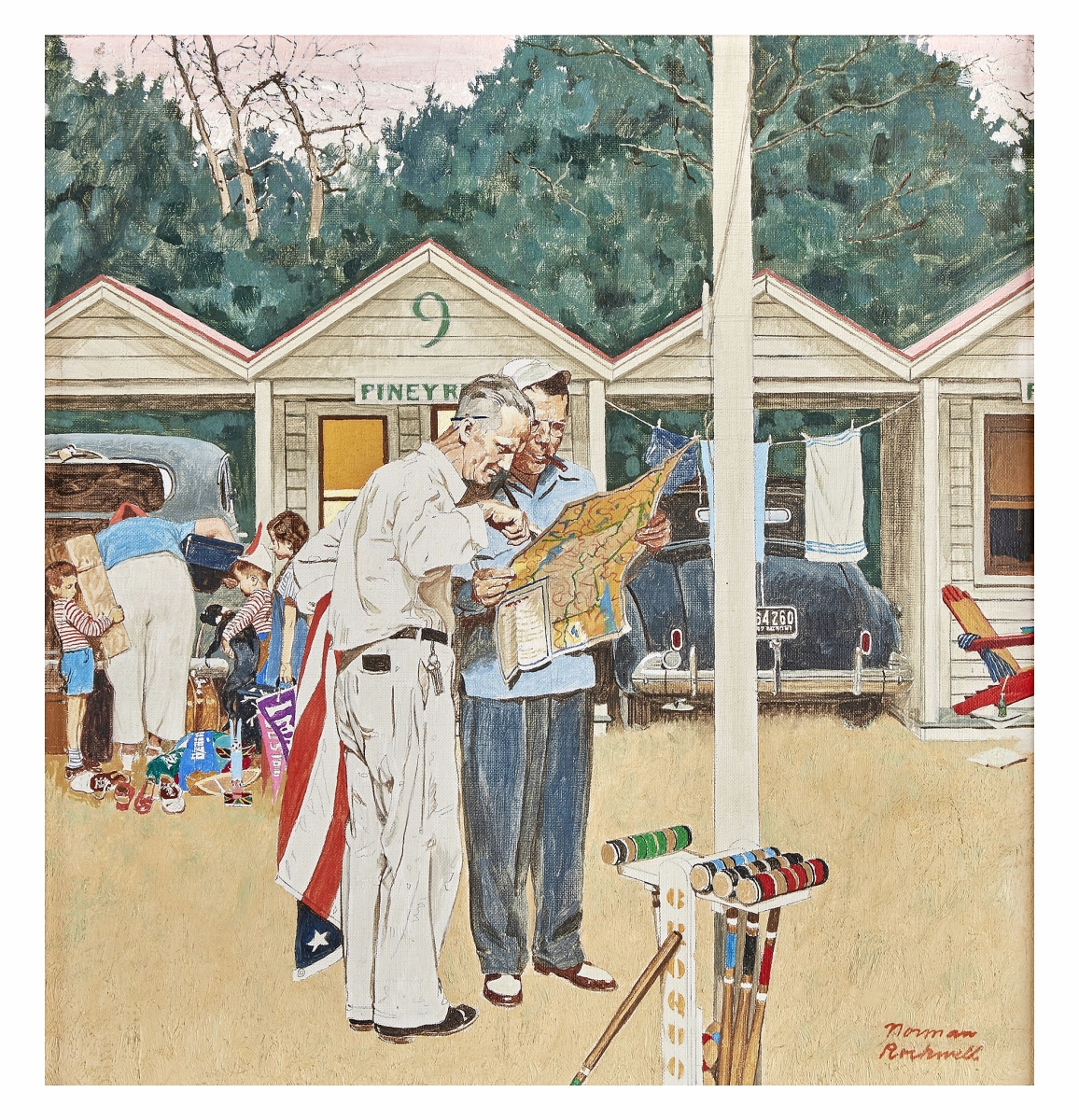

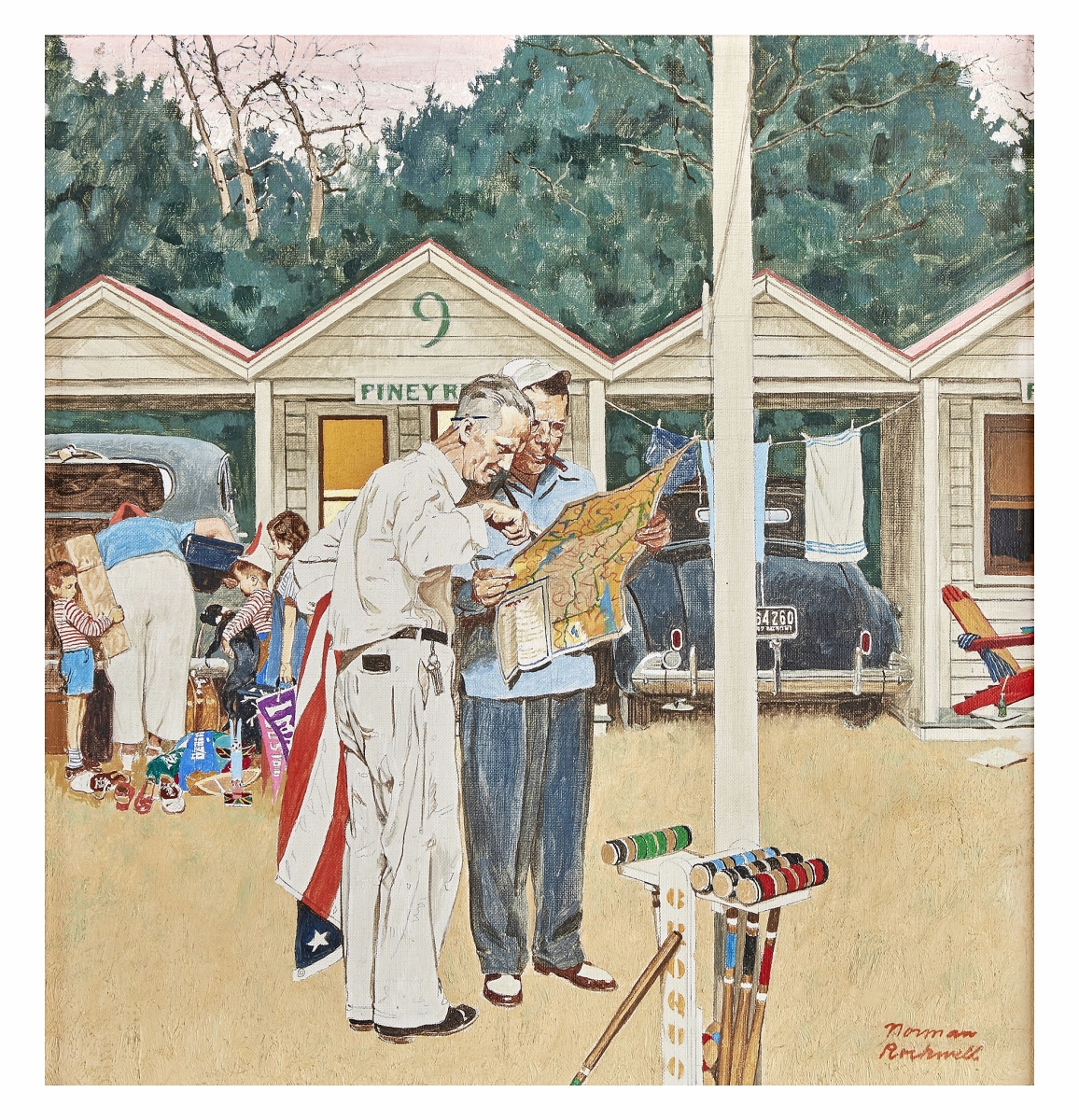

The sale’s leader at $478,000 was a fresh-to-the-market work by Norman Rockwell. “Piney Rest Motel (Cozy Rest Motel)” was originally featured on a promotional poster for the Famous Artists School, a mail correspondence school for aspiring artists that Rockwell taught for. Rockwell had gifted the work to the family through which it descended until now. Oil and pencil on canvas, 18 by 17 inches.

Cecily Langdale, wife of the late Roy Davis and president of Davis & Langdale Company, is putting together a catalogue raisonné on the artist. She had no release date in mind, calling it a “work in progress,” though she said his lifetime output was between 200 and 250 paintings, with additional works on paper.

In a conversation with Antiques and The Arts Weekly, Langdale said, “He has always suffered by his pictures being small and us not being a hot shot gallery. Had he been more productive, I have no doubt other galleries would have gone after him. Many years ago, Anthony d’Offay wanted to do a York show, but there wasn’t enough material.”

Langdale described York as a good friend of hers who was quiet and reserved. “He kept himself apart from the art world,” she said. “He was a lovely man, I think a genius.”

When asked if York collected art, Langdale replied in the negative. “He did not collect at all, he lived a very simple life. He was not friends with other artists, he was very solitary.”

Prior to the sale of “Bird Girl” in Freeman’s June 6 sale, Sylvia Shaw Judson’s auction record stood at a modest $3,250. It now stands at $390,600 for the 50-inch bronze work that entered the American consciousness when its first casting was featured on the cover of John Berendt’s best-seller Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. The work was cast in an edition of four, this the second cast that was exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1938 before traveling to five other institutions. Alasdair Nichol said the firm found it tucked away in a wine cellar. It was purchased by Olde Hope Antiques bidding on behalf of a client.

In 1995, in one of the only interviews York ever gave, the New Yorker described him as “the most highly admired unknown artist in America.”

“The phrase is overused, but he was really a painter’s painter,” said Alasdair Nichol, chairman at Freeman’s. “Fairfield Porter, Wayne Thiebaud – he was known to all of them, they were admirers. In my experience, the great pecking order of the market is defined by the artists who strike a chord with their peer group first. Then it goes from critics to curators and gets out to the world. A lot of other artists were huge admirers of York.”

In a recent Zoom interview with Lois Dodd and Wayne Thiebaud hosted by UC Davis, moderator Karen Wilkin asked the artists which contemporary they admired most. Thiebaud replied with Albert York.

Other artists with York in their collections included Susan Rotheberg and Edward Gorey.

Major collectors of American art added York to their rosters through Davis. Among them was Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, Paul and Bunny Mellon, Werner and Sarah-Ann Kramarsky and Lauren Bacall.

Unlike his more expansive views, Daniel Garber (1880-1958) focused on a domestic scene in “Houses — Shannonville.” The work was purchased directly from Garber by the family through which it descended. At 29½ by 27½ inches, it sold for $189,000.

It seems that York was as enigmatic in life as he was after – only 13 paintings, including the six sold in Freeman’s June 6 American Art and Pennsylvania Impressionists sale, have appeared at auction, according to Askart.

When asked if he was worried about flooding the market, Nichol said, “We had a stack of interest, that was never a concern. When we did a sale before with eight Garbers, I was worried about that. But with York, he’s so scarce in the market. Most people haven’t handled him. I noticed the first record was at the Bacall sale, two little oils and they made $160,000. I thought obviously there was something going on. I was very excited to have these works.”

On the dearth of works at auction, Langdale noted that many of his paintings come back to her gallery and she continues to organize loan shows, including one this past fall at Meredith Ward Fine Art. At 12 works strong, Langdale called it one of the largest York offerings to come to sale at one time in more than 40 years.

Back at the auction, Nichol said interest came from art advisors representing the upper echelon of collectors and, probably, institutions.

All six of the works on offer came from a Reading, Penn., collection, placed there through Davis. Nichol described the consignors as businesspeople and travelers who collected top artists, including Barbara Hepworth. “They were sophisticated people with a very distinct and thoughtful aesthetic. To buy six works by one artist who had such a small output, it says a lot about the collectors and their eye,” Nichol said.

On Albert York’s “Reflections in the Pond,” scholar Martin Herbert observed, “God knows what time of day or night it is – the scene looks dipped in precious metals.” With a green aura, the 24-by-20-inch oil on canvas sold for $163,800. The work was featured in the artist’s first sold-out exhibition at Davis Galleries in 1963.

York’s five oils and one watercolor would produce a combined $685,440.

They were led by a $239,400 result for “Still Life: Green Apples,” which produced an auction record for the artist, selling to a Philadelphia collector who had never done business with the auction house before. Freeman’s broke the artist’s previous auction record twice in this sale. The 20-by-22-inch oil on canvas features a plate of green apples on a table, three apples placed around directly on the table, all on a white tablecloth and before a green wall background. Relative to this painting, Freeman’s wrote, “York’s paintings owe a great deal to European artists such as Édouard Manet, Paul Cézanne, and Giorgio Morandi, though his inspiration also remained rooted in American Art.”

Nichol said this painting was quite popular among previewers, splashing across Instagram in the lead up to the sale. “It struck me as a little more conventional, less typical as his others,” he said. “He was known for doing pastoral scenes and still lifes. I hadn’t seen anything like this, but there was no question it was a very appealing painting.”

More in line with the artist’s reputation was a green-tinged landscape featuring two trees and a small pond, its aura similar to the way in which NASA’s images of Mars all appear orange – from the ground to the skyline to the atmosphere. It found $163,800. The auction house said the green oasis, circa 1960, is early for York and was included in his first solo exhibition at Davis Galleries, which sold out. Scholar Martin Herbert observed, “God knows what time of day or night it is – the scene looks dipped in precious metals.”

In a letter accompanying this painting of the Old Grist Mill in Warrington Township, artist George Sotter wrote, “The beautiful stone building, which was the inspiration for the painting stood between Carversville and Lumberville and served both man and beast for well over a century as the chief grist mill of the community. The beauty of the building’s proportions, plus the lovely native stone made it one of the gems of our county. These qualities inspired this; one of my best paintings.” It sold for $163,800.

At $100,800 was “Jar of Wildflowers,” a 10-7/8-by-10½-inch oil on panel still life. Coming in at $88,200 was a 10-by-8-inch oil on canvas portrait titled “Ostrich Feathers (Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, Virginia Caldwell),” which is a rare depiction of an intimate subject for York. A more familiar motif was found in “Cow,” a 7¾-by-11-inch oil on panel pastoral scene featuring a brown and white cow amid a sun-splashed field with a singular tree in the top right corner. In 1975, artist Fairfield Porter wrote of York’s cow paintings, “He identifies with his subject, whether a tree, a cow, a glass of flowers, or the woods. But not only with the subject: he also identifies with his materials, and with the translation of the identification with the cow into an identification with the paint he uses to present the cow.”

Found tucked away in the depths of the wine cellar of the same Reading, Penn., collection was Sylvia Shaw Judson’s “Bird Girl.” Freeman’s called it “one of the most recognizable American sculptures to ever appear at auction.” The 50-inch bronze was conceived in 1936 and cast in an edition of four in 1938. This sophomore casting, numbered 2 of 4, went on exhibit at Shaw’s solo show at The Art Institute of Chicago that same year before it traveled to five other institutions on a tour. When it arrived at the Dayton Art Institute in April, 1939, a Mr and Mrs Edward L. Ryerson sent note that they would like to purchase it. They used it as a garden statue for their summer home in Marion, Mass., and it descended in the family ever since, this its first appearance on the market.

“Bird Girl” entered the American consciousness when the first casting was featured on the cover of John Berendt’s 1994 best-seller Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. It was purchased for $390,600 by a client through the New York City/New Hope, Penn., dealership Olde Hope Antiques.

Albert York’s “Jar of Wildflowers” bloomed to $100,800. He created it in 1966 and it went on exhibition at Davis & Long Company in 1977. Oil on panel, 10-7/8 by 10½ inches.

“It’s such a well-known image, when we saw it, we thought it must have been a copy,” Nichol said. “But it had the Roman Bronze Works stamp and we knew four were made. If you wanted one, this was your only chance to get it. We had interest from the South, but we also had a phone bidder from the Far East.”

With so few Judson works on the market, estimating it was a bit tricky, Nichol noted. “We said, ‘who knows what it’s worth.’ We really believed in it as an iconic sculpture, but we had to price it accordingly. We felt it was certainly not worth less than $100,000, certainly worth more. I did a video based around it, we did a photo shoot with it, had it up on our roof. It really lends itself to posing. People who saw it really loved it.”

According to Askart, Judson’s auction record stood at $3,250 before the sale – it is now 120-times that.

Still higher was the sale’s top lot, a fresh-to-the-market Norman Rockwell oil and pencil on canvas titled “Piney Rest Motel (Cozy Rest Motel)” that brought $478,800. Rockwell gifted the circa 1950 work to a friend in Maine and it descended in that family ever since. The painting measured 18 by 17 inches and featured an image of a father holding a map in both hands as he asks directions from the inn owner, his wife and kids behind loading up the car. It is a quintessential summer scene.

An intimate subject for the reclusive Albert York is found in “Ostrich Feathers,” a portrait of his wife, Virginia Caldwell. The 10-by-8-inch oil on canvas sold for $88,200. Circa 1964, it is an early work for York, who began exhibiting at Davis Galleries just a year earlier.

“Paintings are a bit seasonal,” Nichol said. “So many of the Pennsylvania Impressionists did snow scenes, and a few sellers thought they should wait for our next sale in December. Summer paintings sell well in the summer. It was just a classic slice of Americana.”

The work appeared in a promotional poster for the Famous Artists School, a mail correspondence art school that Rockwell taught for. Nichol said it sold to a southern American buyer.

The other half of the sale, works from Pennsylvania Impressionists, sold particularly well. Nichol noted strong results for women artists, including Fern Coppedge (1883-1951) and Mary Elizabeth Price (1877-1965). Coppedge found $88,200 for “Lumberville House in Winter,” an 18-by-20-inch oil on canvas that was featured in a 1990 exhibition at the James A. Michener Art Museum. “Mallows,” a 30-by-30-inch oil with gold leaf on canvas by Price sold for $75,600.

Other women outside of Pennsylvania would do well, including Louisiana painter Helen Maria Turner (1858-1958). Her “The End of My Porch” was shown at four museums – including the Corcoran Gallery of Art – in four separate shows in 1915. She painted it while at Cragsmoor, an artist’s colony in the Shawangunk Mountains that fielded artists like Curran, George Inness and William Beard. The work, 16 by 14 inches, brought $88,200.

Selling for $81,900 was “Cow,” a 1971 oil on panel by Albert York. He created the work in 1971 and exhibited it with Davis & Long Company in 1977.

Selling for $189,000 was “Houses – Shannonville” by Daniel Garber (1880-1958). The painting had been purchased directly from Garber and remained in that family ever since. The scene was painted on the side of a creek in Shannonville along the Schuykill River Trail.

On the scene, Nichol said, “It’s not necessarily the kind of Garber many collectors go for. It wasn’t so expansive, it was more focused and subtle.”

A nocturne by George William Sotter (1879-1953) lit up the block when it sold for $163,800. “A Bucks County Landmark” depicts the Old Grist Mill in Warrington Township, one of the oldest historic sites in the town, erected 1756.

In a letter accompanying the work, Sotter wrote, “The beautiful stone building, which was the inspiration for the painting stood between Carversville and Lumberville and served both man and beast for well over a century as the chief grist mill of the community. The beauty of the building’s proportions, plus the lovely native stone made it one of the gems of our county. These qualities inspired this; one of my best paintings. May the pleasure of its creation pass to you its possesser, is the wish and hope of, Sincerely, George W. Sotter.”

Painted during her time at the artist colony Cragsmoor was Helen Maria Turner’s (1858-1958) “The End of My Porch.” While other artists ventured into the valleys and forests in the Shawangunk Mountains during their time at Cragsmoor, Turner chose to remain near her cabin and its accompanying garden, content with the inspiration there. This work, an oil on canvas laid down to board of 16 by 14 inches, sold for $88,200.

Nichol said the sale grossed just shy of $3.5 million, bringing Freeman’s American Art department to more than $10 million in gross sales over the last year with just 200 lots. The June 6 sale was 91 percent sold.

“This is the best year for American Art that we’ve ever had,” he said. “We’ve got our gross on just 200 lots, we’re not talking about thousands of lots. We’re homed in on the market. Freeman’s is getting a nice reputation for finding things – we’re discovering works of art. Nobody knew about this Rockwell, the Judson or the Yorks. These are all fresh to the market.”

For additional information, www.freemansauction.com or 215-563-9275.