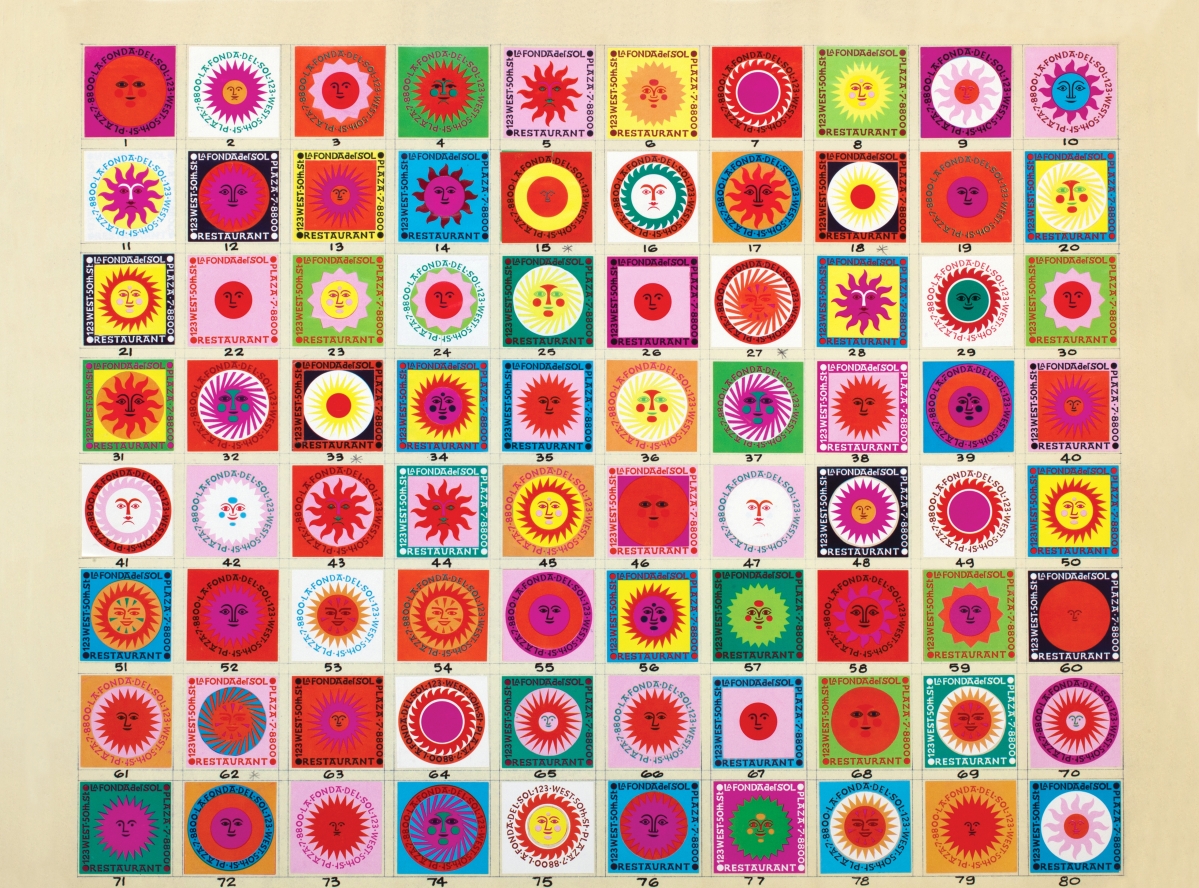

Design for matchboxes of the restaurant La Fonda del Sol, New York City, by Alexander Girard, 1960. Vitra Design Museum, Alexander Girard Estate

By Karla Klein Albertson

BLOOMFIELD HILLS, MICH. – At first reveal, the lifetime production of Alexander Girard (1907-1993) sounds like the accomplishments of a dozen designers. His multiplicity of abilities as an architect, product designer, textile creator and serious collector of folk art may have made him less well-known rather than more famous. This may be due to the fact that his work is simply more difficult to define and pigeonhole than contemporary friends and collaborators, such as Charles and Ray Eames, George Nelson and Eero Saarinen.

“Alexander Girard: A Designer’s Universe,” an exhibition with accompanying catalog organized by the Vitra Design Museum and on view at the Cranbrook Art Museum through October 8, should be the key that brings the designer’s work into proper focus within the scheme of Twentieth Century art history. Vitra holds Girard’s extensive archives in its vaults, and a recent analysis and overview of the material became the foundation for the exhibition, which had its premier last year at the German museum. The Cranbrook played an important role in the designer’s career.

In his introduction to the catalog, chief curator Jochen Eisenbrand emphasized the breathtaking diversity of the designer’s output: “Every visitor who delves into the estate of Alexander Girard held by the Vitra Design Museum is overwhelmed by the formidable degree of productivity, variety, creative richness and obvious joy in the design process that is reflected in his designs…. Anything that could help make our surroundings more attractive and enrich everyday life was important to Girard; nothing was too small or irrelevant.”

Girard’s early life was a sophisticated mix of international travel and education. Visitors might ask why Michigan – rather than Rome, London or New York – played such a key role in the designer’s ultimate success. Girard was born in New York City to an American mother and French Italian father, but they soon moved to Florence, Italy, where he spent much of his childhood. As a young man, he attended boarding school in England and, in the 1920s, took an architectural degree in London, but even then he displayed a talent for interior design.

Moving to New York City in 1932, he set up a studio taking commissions for furniture design and interiors. There he married Susan Needham, who became a supporter and partner in his pursuits, and in 1937 they moved first to Detroit and later to the prosperous suburb of Grosse Pointe. The couple lived not far from the Cranbrook Academy of Art, where Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen were studying. These were among the Michigan contacts who would prove to be lifelong friends and collaborators.

Moving to New York City in 1932, he set up a studio taking commissions for furniture design and interiors. There he married Susan Needham, who became a supporter and partner in his pursuits, and in 1937 they moved first to Detroit and later to the prosperous suburb of Grosse Pointe. The couple lived not far from the Cranbrook Academy of Art, where Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen were studying. These were among the Michigan contacts who would prove to be lifelong friends and collaborators.

At that time, Michigan was not a backwater but the place to be for creative minds in design. Andrew Blauvelt, director of the Cranbrook Museum, explains, “Detroit was the happening city, probably the most important city in the world at that moment. Girard was doing product design – radio cases for Detrola, a Detroit-based manufacturer. I think Eames was looking at some freelance work at Detrola. They both had architectural training but were also doing product design. And this would have been at the moment when there was a lot of activity in that field at Cranbrook.”

Numerous milestones marked Girard’s Michigan years and made an impact on the course of his career. In 1939, he and Susan went on a delayed honeymoon to Mexico and began a lifelong collection of folk art, which would thereafter influence his work and physically enhance his projects. In 1945, he opened his own store in Grosse Pointe, and the business broadened into interiors for homes, office spaces and even industrial situations. In 1949, Girard organized a groundbreaking exhibition, “For Modern Living,” at the Detroit Institute of Art.

The most important breakthrough came toward the end of 1951, when his friendship with Charles Eames and George Nelson led to Girard’s appointment as director of the new textiles division at Michigan furniture manufacturer Herman Miller. His mastery of this position still leads many to think of Girard as primarily a textile designer.

Alexander Girard with Ray and Charles Eames while setting up the “Good Design” exhibition at the Merchandise Mart Chicago, 1953. Vitra Design Museum, Alexander Girard Estate

At that time, neutral and unpatterned textiles provided an unstimulating office environment. Herman Miller’s designer bio on its website quotes Girard as saying, “People got fainting fits if they saw bright, pure color.” The firm’s profile then chronicled his contribution: “At Herman Miller, Girard had the freedom to express himself. With primary colors, concise geometric patterns and a touch of humor, he injected joy and spontaneity into his designs. During his tenure, he created over 300 textile designs in multitudes of colorways, wallpapers, prints, furniture and objects. Girard’s work with Herman Miller continued until 1973 and included spicing up the Action Office system with a series of decorative panel fabrics.”

Continuing to produce major textile collections for Herman Miller, the Girards followed the trail of their cherished folk art and moved to Santa Fe, N.M., where they transformed an old adobe house for their home and Susan set up a shop in town. Blauvelt notes, “He had been collecting folk art his entire life. Santa Fe was the mecca for a lot of artists, and he wanted that kind of atmosphere to create in. He used the inspiration of his folk art as an integral part of his interior design practice. That’s what distinguished him from others, that was the ‘secret ingredient’ that led to the modification of conventional Modernism. He was inspired by the colors, by the handcrafted quality, by the textual variants – all of these elements become part of his design vocabulary.”

To even outline the projects of this multifaceted artist is impossible within the scope of a single article. Fortunately, the exhibition catalog contains a detailed biography and essays by six different scholars on aspects of Girard’s career. But one example, the creation of the interior of the storied New York City restaurant La Fonda del Sol, demonstrates both the influence of his study of folk art and his amazing ability to design every minute detail of a project. Opening in 1960 in the Time-Life Building on West 50th Street, La Fonda was an inspired early example of the “theme restaurant,” in this case with a focus on a romantic interpretation of Latin America. Girard designed everything from wall treatments and lighting to napkins and matchbooks; folk art was installed in inset cases lining the walls.

Barbara Hauss, who wrote the catalog chapter on “Designing for Dining: Restaurants by Alexander Girard,” described it thus: “The ‘inn of the sun’ announced itself to passersby with its Spanish name spelled out in a playful font, augmented by a large sun sculpture above the door of the glazed vestibule facing 50th Street. A view of the inside was obscured by a patchwork of metal foils that covered the windows. Upon walking through the door, one entered a world of its own, characterized by Girard as ‘an abstract symbol’…a special ‘stage world’ and not a historically or realistically accurate reproduction of any given place or prototype.'”

Armchair No. 66310, design by Alexander Girard, 1967. Series production by Herman Miller Furniture Co., collection Vitra Design Museum. —Vitra Design Museum photo, Jürgen Hans

The Sixties had begun, and Girard – who had anticipated the bright Pop of the decade in his textiles – was the perfect designer to engineer the complete transformation of a corporate brand. A statement by Girard about his inspiration was discovered in the Herman Miller archives and is quoted in the catalog by its executive creative director Ben Watson: “My greatest enjoyment and satisfaction in the solution of any project is uncovering the latent fantasy and magic in it and convincing my client to join in this process.”

In 1965, Girard worked that magic on Braniff Airlines, in the firm’s memorable “End of the Plain Plane” campaign. He designed everything from the plane’s exterior and interior color schemes to the ticket counters inside and food service details, while fashion favorite Emilio Pucci created the uniforms. In that era, if you flew with Braniff, you were part of the “Sixties swing.”

At Cranbrook, Blauvelt said he is delighted with the public reception of the exhibition: “There’s a real kind of richness and a lot of layering to the work, even a three-dimensional collaging. Visitors to the exhibition are wowed by all the color and texture – it’s a very cheerful display. Why he’s so popular now is that his work is resonating with people again – he was so multifaceted. And he’s linked to the continuing popularity of Midcentury Modern, which never seems to die. So, Girard’s style is very much contemporary in that sense – his use of color, pattern. He was also influenced by Pop art – you can see that in some of his work.”

Blauvelt continued, “His last project with Herman Miller was the creation of environmental enrichment panels. They had created a cubicle system for offices, and the panels used very Pop images and iconography, which added color and helped humanize the space.

“There is one amazing section in our North Gallery, near the restaurant design material. It’s a very long L-shaped case that is a sampler of the projects he was working on in other parts of the country, taken from the archives, but presented as Girard himself would have presented them. It’s this very dense, very layered presentation, but still very orderly. There are drawings, scale models, samples of actual products – a combination of elements that is a good visual representation of the archives he left behind.”

In addition to the exhibition catalog, Folk Art from the Global Village: The Girard Collection at the Museum of International Folk Art by Jack Lenor Larsen offers a further exploration of the Girards’ collecting interests. The couple donated their holdings – more than 100,000 objects – to the state of New Mexico in 1978. Girard created the installation, which can be seen in the museum’s Girard Wing.

The Cranbrook Art Museum is at 39221 Woodward Avenue. For information, 248-645-3323, or www.cranbrookartmuseum.org.

Journalist Karla Klein Albertson writes about decorative arts and design.