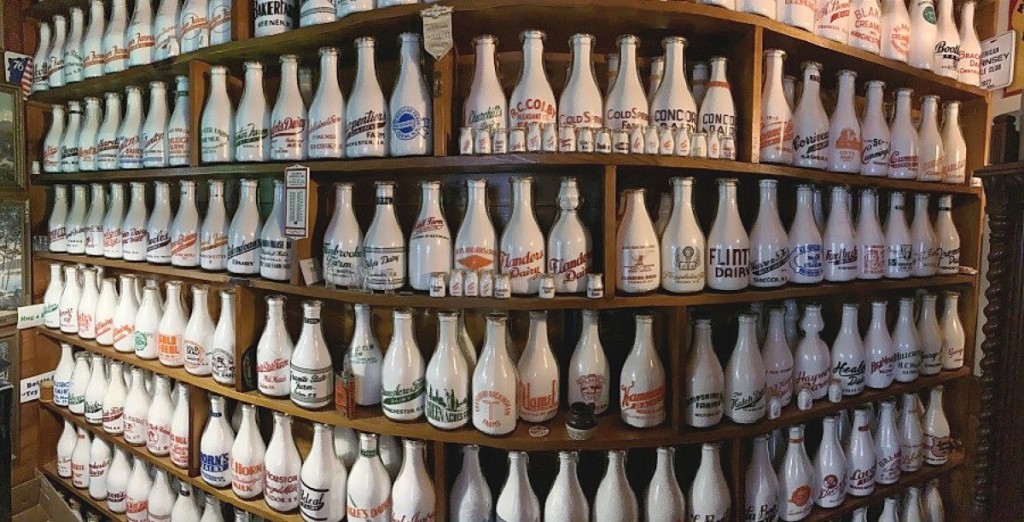

Swanson’s milk bottle collection was nearly encyclopedic with more than 250 different New Hampshire dairies represented, a portion of which is shown here. Collectively, the bottles brought $6,000.

Review by W.A. Demers, Photos Courtesy Paul McInnis Auctions

STRAFFORD, N.H. – The late Rick Swanson was an enthusiastic collector of all things old and of New England – and especially New Hampshire. Included in his estate and selling at a Paul McInnis auction on October 28 were more than 650 lots, including items such as Swasey stoneware crocks, jugs and bean pots, Charles Sawyer colored prints of New Hampshire scenes and vintage soda, beer and tobacco advertising items. The unreserved auction was conducted online-only on McInnis’ own platform.

Bidders thirsted over Swanson’s milk bottle collection with more than 250 different New Hampshire dairies represented. The bottles brought $6,000. “It took a lifetime to assemble, so it was decided to offer this as a collection,” said auctioneer Paul McInnis.

Swanson displayed such items all throughout his home covering every inch because he loved them. His collection was stored and displayed in built-in cabinets in the basement of his home. There were round quart pyroglaze milk bottles, nearly 400 NH round quarts displayed from A-Z representing at least 250 different New Hampshire dairies, with duplicates or variations filling up the back rows. The same was the case with New Hampshire embossed quart milk bottles, numbering about 360, and, yet another variation, more than 400 New Hampshire square quarts representing at least 230 different New Hampshire dairies.

Swasey stoneware crocks, jugs and bean pots were another category in the sale, ranging from $82 for three Swasey stoneware jugs from Portland, Maine, to $725 for a lot of Swasey miniatures, teapot, two beanpots and a jug.

The bottles tell one part of the story of early New Hampshire agriculture in which dairy was “king.” John Porter, University of New Hampshire extension professor/specialist, emeritus, has written a book on the subject, The History and Economics of the New Hampshire Dairy Industry, and recently issued a supplement to it. Speaking with Antiques and The Arts Weekly, he said, “Dairy farming’s early beginnings in New Hampshire was a kind of sustainable thing. An average farm would have about six cows – the magic number because that’s about the average number that one man could milk by hand at one sitting. And for a cash crop it was very common to sell that product as butter because it was a more stable form to sell and it could go to cities.” Butter, Porter added, was really the market until the advent of oleo-margarine at the turn of the century, prompting small farms, now perhaps with larger herds, to transition to producing and selling fluid milk. “These farmers started getting glass bottles and developing their own logo, bottling raw milk and peddling it in a radius of their neighborhood,” said Porter. “So that when you go searching for antique and vintage milk bottles by town, you’ll find many different logos because each of these farms would bottle their milk, maybe in a little sanitary room off the milk house or in the back kitchen and peddle it around.”

By the 1930s, however, stricter public health regulations spelled the end of most raw milk production since smaller operations could not afford the cost of pasteurization equipment, and then by the 1950s, glass bottles were replaced by cardboard and plastic and home delivery was supplanted by box stores and supermarkets. Ironically, said Porter, a more recent revitalization of glass bottles borne out of nostalgia, perhaps, has been squelched by the advent of COVID-19 and stores’ reluctance to carry them.

Anyone wishing to learn more about the early New Hampshire dairy industry can obtain Porter’s book and 2020 addendum for $25, including postage, by sending a check to Granite State Dairy Promotion, c/o John Porter, 41 River Road, Boscawen, NH 03033.

The sale offered some 100 advertising thermometers. This Coca-Cola thermometer, marked “Made in U.S.A.” and measuring 16 by 6¾ inches, rose to $55.

The sale also offered some 100 advertising thermometers, myriad brass scales and many sets of early New Hampshire porcelain license plates.

There were New Hampshire stoneware crocks and jugs (many with blue decoration), blue spongeware, blue salt-glaze pitchers and stoneware. McInnis dispersed several hand painted fish and game plate sets, brass apple barrel stencils, a collection of record albums, tin toys, Winchester trade sign, cast iron doorstops, coffee tins, Griswold cast iron cookware, vintage postcard albums, glass front oak display cabinets and hand carved decoys.

Evident throughout was Swanson’s pride in his collections. The estate’s trustee said, “Like any person who likes history, [Rick] had a mind for dates, facts and figures and so became very knowledgeable. To him, collecting was everything! He enjoyed every minute of it and was pleased with all he’d accumulated. He loved that his house looked like a museum. To say that he was satisfied would not be accurate, however. Up until the very end, he felt that he had much more to collect. One of the last things he said to me was that he had to get well because ‘I’m not done yet, there’s more to find.'”

For information, 603-964-1301 or www.paulmcinnis.com.