Benner Island buildings, Wyeth’s studio shown center. Photo courtesy Colby College.

By Kristin Nord

WATERVILLE, MAINE – It was an uncharacteristically warm day in late May when the boat filled with a smattering of Colby College staff set off from Port Clyde, Maine, for Allen and Benner Islands. The trip was one of many excursions running over the next few months to introduce Colby faculty to its new island campus.

Inhabitants of these two islands, owned most recently by Betsy Wyeth (1921-2020), can be traced back to the Abenaki people, whose artifacts have surfaced recently in archeological digs. The British explorer George Weymouth (b circa 1585-d circa 1612) landed on Allen in 1605 as part of his expedition to the area now known as Maine; a stone cross commemorates it was also the site of one of the first Anglican services in America.

Betsy bought the 450-acre Allen Island in 1979 and the 50-acre Benner 11 years later with the aim of shaping an environment that would support and inspire her husband Andrew’s (1917-2009) work. But these purchases also spurred her emergence as a full-fledged artist in her own right. Over the next 40 years, and in concert with skilled local craftsmen, foresters and ecologists, the islands became her personal art and science projects. Her vision was to help Allen, which once supported an active fishing community, become a working island again.

Today, Allen’s commercial wharf supports a healthy lobster industry, and landscape and forest management plans have transformed what had been scruffy second growth forest into an oasis of meandering roads and curated vistas. The islands are now dotted with cedar shingled and clapboard buildings that Betsy either designed or imported and restored. Andrew dubbed them “Betsy’s villages.”

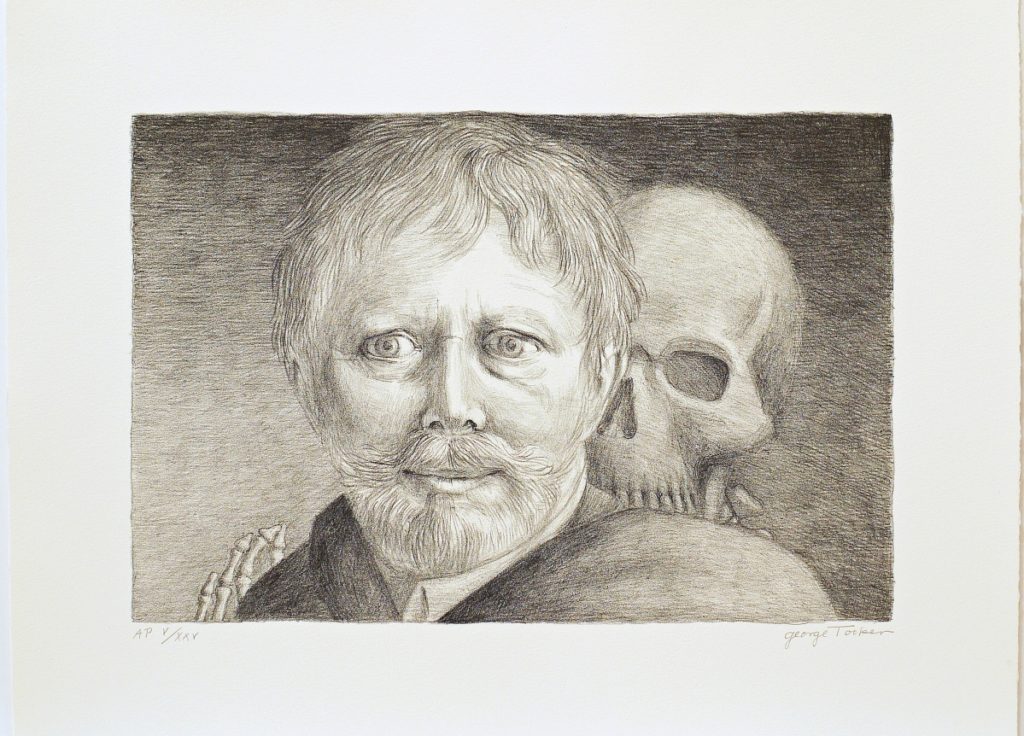

“Self Portrait” by George Tooker, 1996, lithograph, 12 by 18 inches. Colby College Museum of Art, purchase from the Art Department Jetté Acquisition Fund.

Betsy’s swing still hangs from a lintel in the open barn; the ghostly white dorys featured in some of Andrew’s paintings can be found in an historic sail loft that Betsy salvaged in Port Clyde, and reassembled here to serve as a gallery. Then there are Betsy’s distinctive domestic interiors, Shaker-esque in their simplicity, with their curtainless ocean views that appear to whisper “the Wyeths have been here.”

One of Betsy’s innate talents, according to her son, the artist Jaime Wyeth, who splits his year between Southern and Monhegan Islands nearby, was her uncanny ability to delineate drama and to distill the narratives his father might draw upon as he immersed himself in a painting.

“Betsy gets to the core of the thing,” Wyeth himself told his biographer, Richard Meryman. “A hint is all an artist needs – a little glimmer of truth. It’s funny how it smooths the whole thing out.”

Through this intuitive call and response, Wyeth set several significant works on these islands, including “Pentecost,” 1989, which addresses the death of a young woman washed out to sea by a rogue wave; “Airborne,” 1996, which features the reproduction Eighteenth Century Cape Betsy designed for her main residence on Benner; and “Jupiter,” 1998, an otherworldly nightscape. “Pentecost” is currently on view at the Farnsworth Art Museum in Rockland, part of “Andrew Wyeth: Islands In Maine,” an exhibition on view through October 16 that focuses on Wyeth’s island paintings made over a nearly 70-year period.

Installation view of “Andrew Wyeth: Life and Death” at the Colby College Museum of Art. —Luc Demers photo

Colby has had partial access to Allen and Benner islands since 2016 and six scientific research projects are already in the pipeline. Students and their professors will be looking at environmental threats to the ecosystem as well as zeroing in on various species facing extinction. Others will be setting up a weather station and testing do-it-yourself wave monitoring sets.

Allen’s roads traverse freshwater ponds and meadows rich with plant and animal life. Among the major ecological concerns of both islands are the effect that warming Gulf of Maine waters are having on the island’s lobster fishing industry. In another study, students will be collecting data on surface water quality and looking to the extent pollutants blown in from major industrial centers in the United States are affecting the islands’ marine and terrestrial ecosystems.

“The acquisition of Allen and Benner Islands and the partnership with the Wyeth family provide a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to steward the natural and curated environment that holds a special place in the canon of American art. However, stewardship doesn’t imply simple preservation. Rather, it requires building on Betsy Wyeth’s vision for the islands as always evolving and being places of inspiration and learning,” Colby’s president David A. Greene, said recently.

.jpg)

Untitled (Face in Dirt) by David Wojnarowicz, circa 1990, gelatin silver print. 19-7/8 by 23¾ inches. Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Mass., purchased as the gift of Louis Wiley Jr (Penn., 1963) and John Clarke Kane Jr (Penn., 1963) in memory of Paul L. Monette (Penn., 1963) on the occasion of their 50th Reunion, with additional support from the Monette-Horwitz Trust, 2010.

To that end, Colby Museum of Art has already partnered with the Wyeth Foundation of American Art to mount a fascinating exhibition that focuses on a series of pencil drawings Wyeth made in the early 1990s in the Chadds Ford, Penn., home of family friends. “Andrew Wyeth: Life and Death,” curated by Tanya Sheehan, William R. Kenan Jr professor of art at Colby College, introduces viewers to Wyeth’s collection of pencil sketches known as “The Funeral Group,” which were completed in the early 1990s, and then tucked in the Chadds Ford, Penn., home of friends George and Helen Sipala. In 2018, Wyeth’s son, Jamie, received just over 20 drawings from the family; since 2020, additional funeral sketches have been found in the WFA archives.

“This inspired exhibition would not have been made possible without the scholarly expertise of Tanya Sheehan,” Jacqueline Terrassa, Colby Museum of Art’s director, writes in the foreword to Andrew Wyeth: Life and Death, the accompanying exhibition catalog Sheehan has produced. “Her interest in the intersection of medicine and the humanities, the limits of consciousness, and the formation of identity enabled her to revisit Wyeth’s art and see it in new ways.”

The exhibition opened in early June, with much of New England reeling from the threats of Covid-19 spikes amidst the pandemic’s still-alarming peaks and valleys. On the day Sheehan was installing the show in the museum’s Davis Gallery, she said the subject felt eerily appropriate. At a briefing for docents, she added, many had shared their own stories of loss and dislocation. Death was on our collective mind and would be for the foreseeable future.

Wyeth posed existential questions in a vast body of temperas, drybrush paintings and studies, and Sheehan has selected a varied grouping. From the Dickensian scene of the cortege bearing his friend John Olson to his funeral, to works that range in tone from the poignant to the Day-of-the-Dead defiant, Wyeth’s exploration is as voluminous as it is multidimensional.

“Every artist of significance paints life perceived against a background of death,” the arts critic Theodore Wolff has written. “Wyeth does it in such a fashion you can’t separate the two.”

When Wyeth takes on death from various vantage points, his scenes sometimes take on the magical realism reminiscent Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s fiction. In “Breakup,” 1994, for instance, death appears as detritus in the shape of Wyeth’s disembodied hands. In “Spring,” 1978, Wyeth-as-corpse appears shrouded in melting snow. Then there is the oddly jaunty “Dr Syn,” 1981, a self-portrait Wyeth created using an x-ray of his body, in which the artist appears as a skeleton outfitted in a vintage navy coat.

“Ladeira dos Aflitos” by Janaina Tschäpe, 1997, chromogenic print, 31 by 47 inches. Collection of the artist.

Wyeth’s painting, “Winter,” in which a young man descends a dark and barren hill, is believed to be a meditation on the untimely death of Andrew’s father, Newell Convers “NC” Wyeth (1882-1945). Upon inspection, this is Kuerner’s Hill, near the rail crossing where NC Wyeth, and his grandson, Newell, were killed in a train collision in 1945.

In keeping with the museum’s mission as an active teaching institution, Sheehan has taken great care to place Wyeth’s explorations in the context. Sheehan has turned to the work of his contemporaries, as well as to younger Twentieth Century artists who were also wrestling with similar questions. Andy Warhol, a family friend, is painting skulls and car crashes and conjuring appointments with electric chairs; David Wojnarowicz’s self-portrait, (Untitled, Face in Dirt) would become emblematic in the AIDS crisis. Artists Duane Michals, and George Tooker were considering the nature of being as they pictured their own passing. And artists of a younger generation, Janaina Tschäpe and Mario Moore would probe the universality of death as a social experience.

“Because the work of Andrew Wyeth has long been regarded as intensely personal and mysterious, it has often been situated outside the story of American art since the 1960s,” Sheehan said. “This exhibition shows that Wyeth was engaged in existential questions that have long preoccupied conceptual, performance and activist artists.”

In a major sketch in the “Funeral Group,” we encounter Wyeth’s corpse in a casket, surrounded by mourners. They have come together as an assemblage of the dead and the still-living, now joined and yet removed from ordinary time. There are his familiar cast of characters, the models and muses who have been his creative catalysts. Among them is Betsy, in her brimmed hat and customary island attire. As one leaves this exhibit one can imagine the rigorous classroom discussions that are sure to follow. Dr Greene agrees, adding, “At a time when Colby is creating three new art centers, expanding our art collection, and deepening our engagement with artists, curators and art historians through the Lunder Institute for American Art, the islands hold special promise for leveraging all of these assets to ensure Colby College – and Waterville and Maine – are always at the forefront of artistic expression, understanding and inspiration.”

“Andrew Wyeth: Life and Death” is on view at the Colby Museum of Art until October 16.

The Colby Museum of Art, on the campus of Colby College, is at 5600 Mayflower Hill. For information, 207-859-5600 or www.museum.colby.edu.

.jpg)