Review by W.A. Demers

Photos Courtesy of Doyle

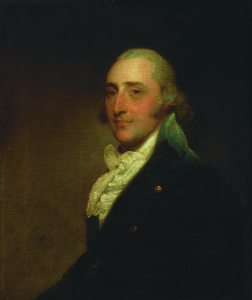

A portrait of a gentleman of the Lee family by the American portrait master Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828) sold for $40,625, far above its $8/12,000 estimate.

NEW YORK CITY — The Metropolitan Museum of Art has done some housecleaning of late, resulting in some authentic “museum-quality” merchandise coming to auction. Later this month, Christie’s will offer British silver, furniture, porcelain and architectural items as the museum prepares a renovation of its English decorative arts galleries. More recently, some choice American paintings from its collection were sold at Doyle on October 7. Highlights included a portrait of a gentleman of the Lee family by the American portrait master Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828), which sold for $40,625, far above its $8/12,000 estimate.

The work has traditionally been identified as a portrait of Charles Lee (1758–1815), attorney general during the administrations of George Washington and John Adams. That is not a unanimous opinion, however, as the catalog notes reveal that the identity of the sitter was first questioned in 1925 by art historian Harry Wehle, the museum’s curator of European painting. It is thought, however, that the portrait was probably painted between 1794 and 1803 when Stuart resided in Philadelphia, the city where Charles Lee also resided until 1801, when he returned to Virginia. A letter dated November 3, 1966, from the Met’s archives by Robert G. Stuart, curator of the National Portrait Gallery, who compared its portrait of Lee attributed to Cephas Thompson believed to depict the sitter a few years before his death, with that by Stuart, wrote, “Putting the photographs… together, I think they could be the same man interpreted by two different artists working twenty years apart.”

“River Landscape (Landscape with Figures),” 1888, by Jasper Francis Cropsey (American, 1823–1900) came from a 20-year private collection on Long Island, and finished at $40,625.

With competitive bidding from buyers in the salesroom, on the telephones and on the Internet, the sale totaled $824,131, at the high end of its estimate. A day after the auction, post-sales were still in progress, according to Doyle’s vice president of American paintings Anne DePietro, and the offering resulted in a strong 82 percent sold by lot and 93 percent sold by value. “The audience [for this sale] was nearly the strongest we’ve had in some time — and we also had works selling to bidders in the audience. Almost everything offered was fresh to the market,” said DePietro, who since coming to Doyle — she was director of Spanierman Gallery and chief curator at the Heckscher Museum of Art previously — has brought a sharper focus to Doyle’s semiannual auctions of American art.

Also by Stuart and from the Met deaccession was a portrait of Charles Wilkes, circa 1794, an oval oil on canvas that notes say was initially done as a rectangular portrait but at some point was cut down to its present dimensions of 301/8 by 251/8 inches. While a historically significant portrait, it did not go to an institution but was won by a left bid from a private collector for $34,375.

Possibly the largest work that Alexander Helwig Wyant (1836–1892) ever did, “In the Still Forest” measured 56¼ by 55¼ inches. Considered a masterpiece of his mature period in the 1880s and formerly in the permanent collection of the Worcester Art Museum, it soared above its $5/7,000 estimate to sell for $37,500 to a phone bidder.

The nephew of John Wilkes, lord mayor of London, Charles Wilkes (1764–1833) came to America toward the end of the Revolutionary War. He became associated with the Bank of New York on its organization in 1784 and in 1794, around the time the portrait was painted, was elected cashier. He served as president of the bank from 1825 until his retirement in 1832. From 1805 to 1818 he was the first treasurer of the New-York Historical Society and along with John Trumbull was an officer of the American Academy of Arts.

People who love American history — and there were many such active buffs in this sale, according to DePietro — had to also love a portrait once thought to be by Stuart but now believed to be a Nineteenth Century copy by an unknown hand. Fetching $20,000 from a private individual and far surpassing its $2/3,000 estimate was a smartly uniformed likeness of Commodore Stephen Decatur, circa 1806–13, an oil on canvas measuring 30¼ by 25 inches. Also consigned by the Met, the story is that the original of this painting by Stuart, done in 1806, was altered sometime before 1847 when the commodore’s widow, Susan Decatur, commissioned James Alexander Simpson to repaint the uniform so that Decatur would appear as he had in 1813 when the city of Philadelphia honored him and he was elected into the Society of the Cincinnati. That painting is in the collection of Independent National Historical Park in Philadelphia.

Severin Roesen (American, 1815–1872) signed “Still Life with Fruit and Grapevines on a Marble Ledge,” oil on panel, 10¾ by 15 inches, with conjoined initials “Sroesen” lower right. It sold for $28,125.

Rounding out the Met collection highlights, a portrait of Thomas Sully’s daughter Ellen Wheeler that Sully painted in 1844 went for $17,500. It is a tender portrait of a young mother with her two little boys but gains significance in that it depicts the artist’s own daughter, Ellen Oldmixon Sully (1816–1896) with her two sons, Charles Sully Wheeler (b 1839) and Levi Woodbury Wheeler (1842–1900). Ellen had married John H. Wheeler, a well-known North Carolina lawyer, diplomat and historian, on November 8, 1838.

DePietro emphasized that the sale was much more than the contribution provided by the Met’s provenance. “We had great regional work, as well,” she said “Landscapes, portraits and still life paintings all sold for multiple times their estimates.”

An emotional favorite for her was “River Landscape (Landscape with Figures),” 1888, by Jasper Francis Cropsey (American, 1823–1900). From a 20-year private collection on Long Island, she had borrowed the painting once for a collecting show at the Heckscher. “It’s just a beautiful piece,” she exclaimed, “not a touch of inpainting. A joy to have.” The top lot in the sale, the view, believed to have been taken from near Cropsey’s home in Hastings-on-Hudson, N.Y., realized $40,625.

Strong prices were realized for other American paintings, including Alexander Helwig Wyant, Severin Roesen, David Johnson, William Coventry Wall and William Sonntag Jr.

Possibly the largest work that Wyant (1836–1892) ever did, according to DePietro, “In the Still Forest,” from the estate of Mary Gayle Kalt, is also considered a masterpiece of his mature period in the 1880s. “This painting is remarkable on many levels,” said DePietro, not the least of which is the botanically correct delineation of New England trees, as well as its size at 56¼ by 55¼. “You need a special house or room to display it,” she said. Once included in the permanent collection of the Worcester Art Museum, this piece soared high above its $5/7,000 estimate, selling for $37,500 to a private bidder on the phone, possibly the highest price achieved for a work from this phase of Wyant’s career.

A silver standout in the sale was this circa 1793 French silver snuff/tobacco box engraved “Charles Carroll” of Carrollton, which was purchased for $11,250 by Homewood Museum, built in 1801 and a wedding present from Charles Carroll to his only son, Charles Carroll Jr.

In addition to the Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century American paintings, the sale featured American silver, furniture and decorative arts from the Colonial period through the Federal and classical styles, including ceramics, mirrors, Chinese Export porcelain, folk art, samplers and rugs. The prints section of the sale offered Audubon, Currier & Ives and topographical prints.

A silver standout in the sale was a circa 1793 French silver snuff/tobacco box engraved “Charles Carroll” of Carrollton. Catalog notes state that Carroll was born in Annapolis, Md., in 1737. A wealthy planter, he served as a representative to Maryland0’s Committee of Correspondence beginning in 1774. In 1776, he was elected to the Continental Congress and was the only Catholic and last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence. He returned to Maryland to assist with the creation of a state government in 1778, and later served as Maryland’s first US senator. Consigned by a Carroll descendant, the box was purchased by the historic house museum in Baltimore, Homewood Museum, which paid $11,250, a high premium above the box’s $1/2,000 estimate. Homewood was built in 1801 and was a wedding present from Charles Carroll to his only son, Charles Carroll Jr. It is now owned by Johns Hopkins University, and together with Evergreen Museum & Library, they form the Johns Hopkins University Museums.

All prices reported include the buyer’s premium.

Doyle’s next American paintings, furniture and decorative arts auction is scheduled for spring. An Impressionist and Modern art sale is set for November 4, and on November 10 the firm will present postwar and contemporary art. For information, 212-427-4141 or www.doyle.com.