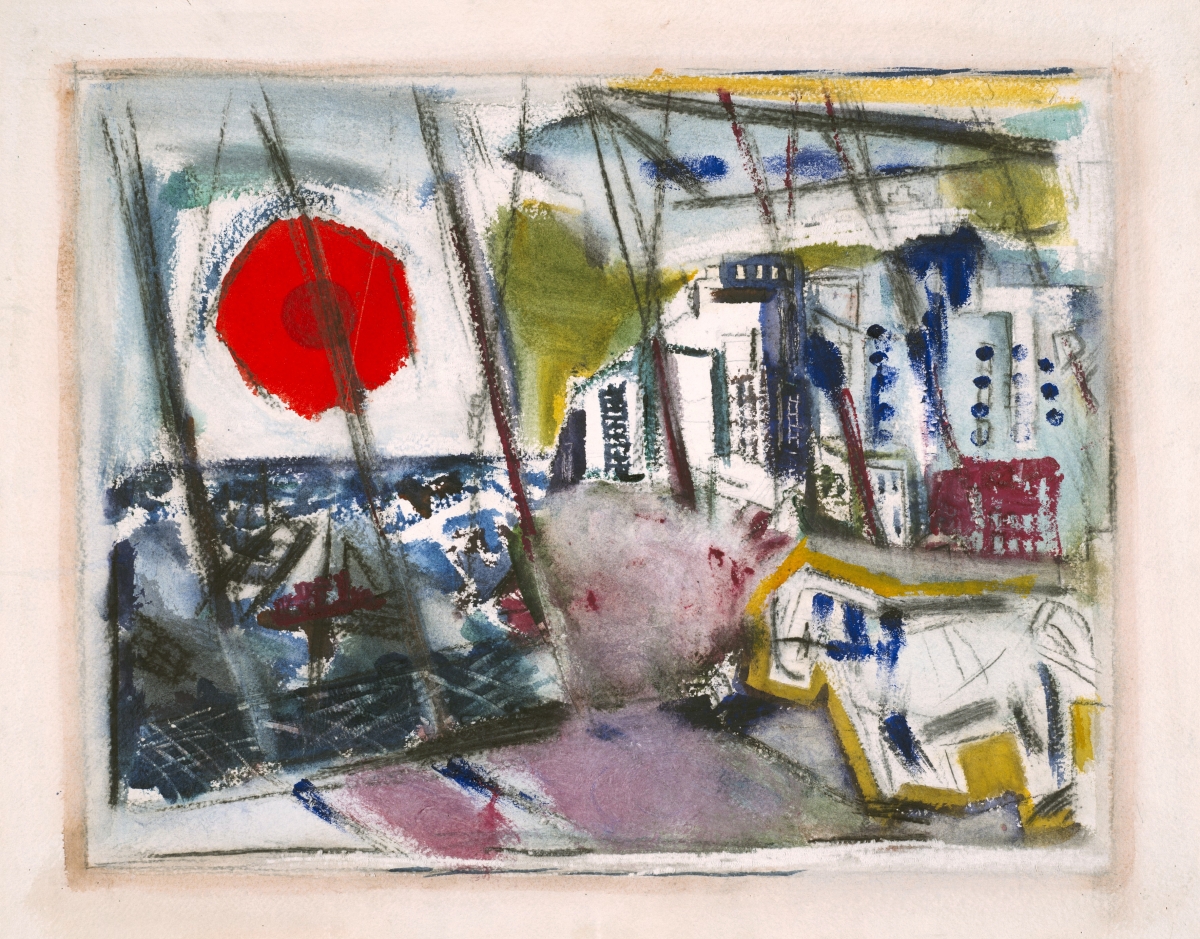

“Diamond Shoal” by Winslow Homer (1836–1910), 1905. Watercolor and graphite on paper. Private Collection.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

PHILADELPHIA, PENN. – “A life’s work” is how Philadelphia Museum of Art director Timothy Rub describes “American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent,” a landmark exhibition on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) from March 1 through May 14. The singular achievement of senior curator Kathleen A. Foster, the show and its accompanying catalog are “a definitive study of the American watercolor movement,” offering an unprecedented opportunity to examine the historical development of this alluring and confounding art form and to see these rare and jealously guarded masterpieces of American art together in one place. Philadelphia is the only venue for this arguably once-in-a-lifetime exhibition, some 15 years in the making.

The freshness and spontaneity we associate with watercolors – translucence, vibrant color and free, gestural brush strokes – disguise the fact that watercolor is, as Rub describes it, actually an “unforgiving and exacting medium.” Unlike malleable, slow-drying oils on a prepared canvas, watercolor paints – solid pigments dissolved in water – are applied directly onto naked paper, where they soak in and dry almost immediately. Mistakes are uncorrectable, revisions impossible.

The bold expressiveness we admire in watercolors by the show’s headliners, Winslow Homer and John Singer Sargent, signals not so much unbridled freedom, but instead a studied surrender to the unique challenges of watercolor. Equally true, it is often the end product of substantial compositional and coloristic planning, not to mention decades of rigorous training and practice. For while Sargent and Homer both cut their teeth on watercolor and employed it as part of their artistic practice from early on, they only really came into their watercolor stride in the full maturity of their careers.

Foster’s own professional history has parallels. “It’s a topic I’ve been working on practically all my life,” she says of watercolor painting in America. Her graduate work on watercolorists Thomas Eakins and Edwin Austin Abbey led to “a lot of little articles and projects,” but while working in smaller museums she was without the substantial resources necessary to pull off an exhibition and publication of this scale. When Foster arrived at the PMA in 2002, she and then-director Anne d’Harnoncourt eagerly discussed the idea of a major watercolor show. Their mutual enthusiasm was enough to get the show on the radar screen, but in a museum with 30 curators, Foster says, “you have a brilliant idea and then you have to put it in line and wait your turn.”

While they were waiting, d’Harnancourt died, and the project was put on hold until Rub arrived and put it was back on the schedule around 2010.

Watercolors are not only difficult to execute, they are also fragile once complete. Paper tears and water-soluble pigments bleed. They also fade irreversibly with prolonged exposure to light. For that reason, art museums rigorously protect their watercolors, allowing them to be exhibited only infrequently, with long periods of “rest” in between. That made the negotiations for loans challenging and complicated, sometimes with complex machinations necessary to get the works Foster wanted. Homer’s famed “After the Hurricane” from the Art Institute of Chicago, for instance, will only hang for half the run of the exhibition. The Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) will swap it out for another Homer watercolor after six weeks. Foster observes that most of these works cannot even be seen at their home institutions on regular museum visits.

Such liabilities meant that some works could simply not be lent, but most museums and collectors were willing to temporarily part with their treasures for what they saw as a truly historic exhibition. “There really hasn’t been a show like this,” Foster observes. Most other major watercolor shows have been either monographic ones – like the AIC’s Homer show in 2008 or the Brooklyn Museum’s Sargent exhibition in 2013 – or they have been collection shows, in which the hosting museum would “bring out their jewels and make an exhibition out of them.”

“Muddy Alligators” by John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), 1917. Watercolor over graphite, with masking out and scraping, on wove paper. Worcester Art Museum.

While such efforts have made major contributions toward establishing a history of American watercolor painting, Foster says, “no single museum has everything, so my mission was to take the best from all these collections to try to tell the whole story.” The result is a broad, sweeping, yet carefully curated group of works selected for their ability to illustrate that story, for their importance in the canon of art history, and for their sheer visual star power. “Every single thing is a gem that I’ve wrangled in for one reason or another,” Foster says.

The exhibition follows the same historical, chronological narrative as the beautifully illustrated and meticulously researched book. Both begin with the formation of professional clubs to host exhibitions and foster appreciation for the medium, which had generally been seen by the American art establishment as amateurish. There was the short-lived New-York Water Color Society and, later, the American Society of Painters in Water Colors, ultimately shortened to the American Watercolor Society, or AWS.

“They were these marginal artists,” Foster explains, “ladies and commercial artists … this little band of outsiders who you’ve mostly never heard of.” Many, like John William Hill, were from Britain, where watercolor was a more respected medium with a longer tradition. These Brits and, soon, American watercolorists were inspired by British aesthetician John Ruskin, who advocated for close attention to nature and painting outdoors. Finding that the portability and quick drying time of watercolors helped them to do just that, artists like Alfred Jacob Miller and Thomas Moran took their watercolor sets with them on their adventures in the West, while Fidelia Bridges and others used the medium to redefine and elevate the longstanding tradition of botanical painting.

Bridges was also a professional illustrator, one of many American artists trained in commercial work who had long used watercolor as their primary medium. The AWS exhibitions offered early opportunities for many in this group, including Homer and Abbey, both of whom produced illustrations for magazines like Harper’s and Scribner’s. Watercolor also helped to launch the American career of the young Thomas Eakins, newly returned from England, whose first sale stateside was a watercolor much like “John Biglin in a Single Scull.”

“Big Springs in Yellowstone Park” by Thomas Moran (1837–1926), 1872. Watercolor and opaque watercolor on paper. Private Collection.

Then came the group we think of today as Impressionists – Theodore Robinson, Childe Hassam, Maurice Prendergast – and the decorators. “In the mid-1870s, people got so excited about interior decoration and the idea of ‘The House Beautiful,'” Foster explains, referencing the title of Clarence Cook’s 1877 book on design. Key figures here are names both familiar and unfamiliar, from stained-glass masters John La Farge and Louis Comfort Tiffany to Tiffany’s protégé Caroline Townsend and many others.

When it comes to star power, it is hard to compete with Homer and Sargent. The two artists share a gallery near the culmination of the show, though in fact they were not strictly contemporaries or peers. Homer was 20 years older and today is best known for the seascapes he painted at his windswept studio on the Maine coast, while Sargent was an expatriate and a cosmopolitan celebrated for his society portraits. Yet watercolors provided a point of intersection as the two artists, well into the second halves of their careers, harnessed their familiarity with the medium to create works of dazzling freshness and immediacy.

This penultimate gallery not only pairs Homer with Sargent; it also pairs Homer with Homer and Sargent with Sargent. Foster says that the comparisons are like a “philosophical treatise” on the difference in mood of the two mediums. “In Homer’s case, the watercolor is happy and colorful, and the oil is labored and dark and about death,” while “for Sargent, oil and watercolor are talking to each other … cross-pollinating in a way that is totally different from Homer.”

The Homer/Sargent showdown is just one of the ways the PMA has ratcheted up the crowd appeal. Watercolor shows can be difficult for viewers: the paintings are generally smaller than oils and the pigments less vivid; they are invariably under glass; and lighting levels must be kept low to protect the works from fading. Foster and her team have mitigated such challenges, in part, by foregrounding watercolor’s relationship to the decorative arts and interior design. The gallery with “The House Beautiful” crowd includes a glorious La Farge window as well as vivid examples of china painting, jewelry and furniture. There is also a gallery that Foster calls the “watercolor salon,” giving a sense of what AWS exhibitions looked like in the 1880s.

The story of American watercolor painting, of course, continues beyond the Nineteenth Century that is the primary focus of Philadelphia’s show. Both the book and the exhibition end with an epilogue that demonstrates how dominant the medium became in the years between Homer’s death in 1910 and Sargent’s in 1925. Illustrators like Jessie Willcox Smith and designers like Violet Oakley achieved unprecedented success and recognition, while Modernists like Stuart Davis, Charles Demuth, Edward Hopper, John Marin, Georgia O’Keeffe and Jane Peterson absorbed the lessons of their predecessors but made the medium uniquely their own.

“The message you get from the last gallery,” Foster says, “is that now watercolor can go in any direction and that everybody’s doing it.” The Twentieth Century piece of the show, she cautions, is meant only as a “springboard” for future conversation and scholarship. “Fundamentally, the whole Twentieth Century is just another exhibition – that’s chapter two,” she laughs. If she is serious, another 15 years is certainly worth our wait.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art is at 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia. For information, 215-763-8100 or philamuseum.org.

Jessica Skwire Routhier is a writer, editor and independent art historian based in South Portland, Maine.