Goat, Northeastern United States, circa 1880. Molded and sheet copper with yellow sizing and gold leaf, 25 by 31 inches; depth of horns, 4 inches. Collection of Julie and the late Carl M. Lindberg; photo Gavin Ashworth, courtesy Allan Katz Americana, Madison, Conn.

By Laura Beach

NEW YORK CITY – A story recounted by Robert Shaw, author of American Weathervanes: The Art of the Winds and guest curator of the companion exhibition of the same name at the American Folk Art Museum (AFAM), suggests the ways in which these exuberant sculptures are, if not folk art, the quintessence of Americana. Seeking new weathervanes to offer consumers, Boston manufacturer Leonard W. Cushing (1830-1907) instructed ornamental carver Harry Leach (1809-1885), a maker of wooden models, to “carve some horses for us,” horses by then the most popular American weathervane form. Cushing continued producing vanes introduced by his predecessor Alvin L. Jewell (1821-1867), but he wanted something new. Perhaps inspired by the 1867 race between the legendary trotter Ethan Allen and his upstart challenger, Dexter, and familiar with Currier & Ives’ lithograph of the contest, Cushing asked Leach to model the two steeds. Cushing’s appropriation is a clear instance of America’s imagery-making machinery at work, of popular culture repurposed in the service of national identity. As AFAM director and chief executive officer Jason T. Busch wryly observes, “Weathervanes are markers of so much more than the weather.”

AFAM is a fitting venue for the show. Dealer Adele Earnest (1901-1993), a founder of the museum, was among the first to scout weathervanes, which early on she marketed through New York gallerist Edith Halpert. One of the first exhibitions the then-fledgling museum mounted, in 1965, was “Turning in the Wind: Weathervanes and Whirligigs.” The museum presented the last major display, “The Art of the Weathervane,” in 1979-80. Until now, two of the most influential books on the subject were American Folk Sculpture by Robert Bishop (1974) and the less visual but more assiduously researched Yankee Weathervanes by Myrna Kaye (1975). Clearly, it was time for another look.

Shaw took up the subject at the urging of Jane Katcher, a collector of American folk art and a co-creator of the new online journal Americana Insights. A prolific author and past curator of the Shelburne Museum, Shaw begins where Kaye leaves off. The first to document the maker J. Howard, Kaye, who died in April, also dug into the history of Cushing & White, inspecting L.W. Cushing’s journals at the Waltham Historical Society in Massachusetts.

Church banner by unidentified artist, Orono, Maine, circa 1840. Sheet iron, lead, copper and blown glass with remnants of an early gilded surface, 61 by 74¼ inches. Private collection; photo Ellen McDermott, courtesy Olde Hope Antiques, Inc.

“I knew Waltham was central to the story and that there were makers, about whom little or nothing was known, who predated Jewell and Cushing & White,” says Shaw, who built upon his predecessor’s book and research notes, the latter shared with him by the box full by Kaye and her son Steve. He recruited to the project former Shelburne Museum interns Sloane Stephens Awtrey, who delved into early Massachusetts makers, and Bill Brooks, now director of the Henry Sheldon Museum in Middlebury, Vt., and a student of patternmaker Leach.

Dedicated to Katcher, Kaye and Julie Lindberg – like Katcher, a lender to the show and early, unflagging supporter of the project – American Weathervanes: The Art of the Winds is visually engaging, combining much new photography of the best American vanes with an arresting assortment of archival material, some of it recently uncovered and published for the first time. Expanded biographical profiles of the commercial makers who flourished in Boston and New York before and after the Civil War form the meaty heart of the study, which Shaw enlivens with fresh narrative detail.

Like the 2019 AFAM book and exhibition “Made in New York City: The Business of Folk Art,” this mercantile history highlights the robust capitalism, fluctuating fortunes and serial collaborations that characterized American enterprise in the Nineteenth Century. Commercial weathervane manufacturing, which Shaw defines as “the creation of multiple copies of identical forms using patterns and molds,” began in Massachusetts, primarily in the Boston area, perhaps as early as the 1840s. The processes involved were anything but mechanical. As Shaw explains, “Commercial vanes were made in tiny assembly lines, but every bit was handwork. The art of the weathervane came out of America’s craft traditions, which is what interests me.”

“Fame,” attributed to E.G. Washburne & Co., New York, circa 1890. Molded copper and cast zinc with traces of gold leaf, 39 by 35¾ by 23½ inches. American Folk Art Museum, gift of Ralph Esmerian, photo Gavin Ashworth.

Shaw writes that the “earliest Massachusetts weathervane manufacturers of extant, identified vanes were the Boston coppersmith William F. Tuckerman, who began working in the late 1830s and may have been making vanes in the 1840s; J.&C. Howard & Co. of West Bridgewater, which was first listed as a vane manufacturer in 1853 but was wholesaling vanes by 1850 and possibly earlier; and A.L. Jewell of Waltham, who founded a metal-working business there in 1852 and numbered vanes among his wares.”

Much of the team’s research on Tuckerman and Isaac S. Tompkins, who like Tuckerman was a coppersmith who made a variety of products, is new. Tuckerman, Shaw writes, ran a large shop, with two or three times as many men as employed by Howard or Jewell. Though his known output was small, Tuckerman may have made many early, unattributed Boston-area vanes. At least four horses, perhaps dating from the 1840s, are stamped “Tuckerman Boston.” They have distinctive drilled eyes, unlike Jewell vanes, which have molded eyes. Shaw identifies Tompkins – who had miniature portraits of himself and his wife painted by his friend Rufus Porter around 1820 – as the earliest known US maker to manufacture molded copper vanes based on wooden patterns, and to advertise them, something he did as early as 1852. Regrettably, no Tompkins vanes have been confirmed, nor has his patternmaker been identified.

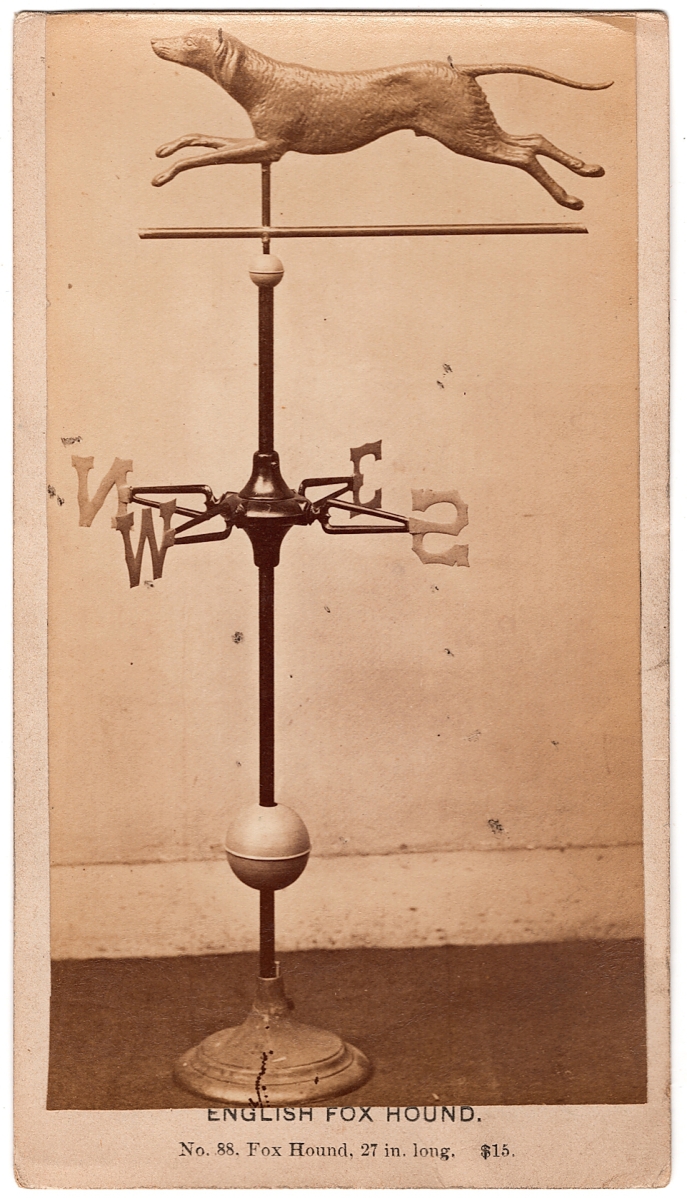

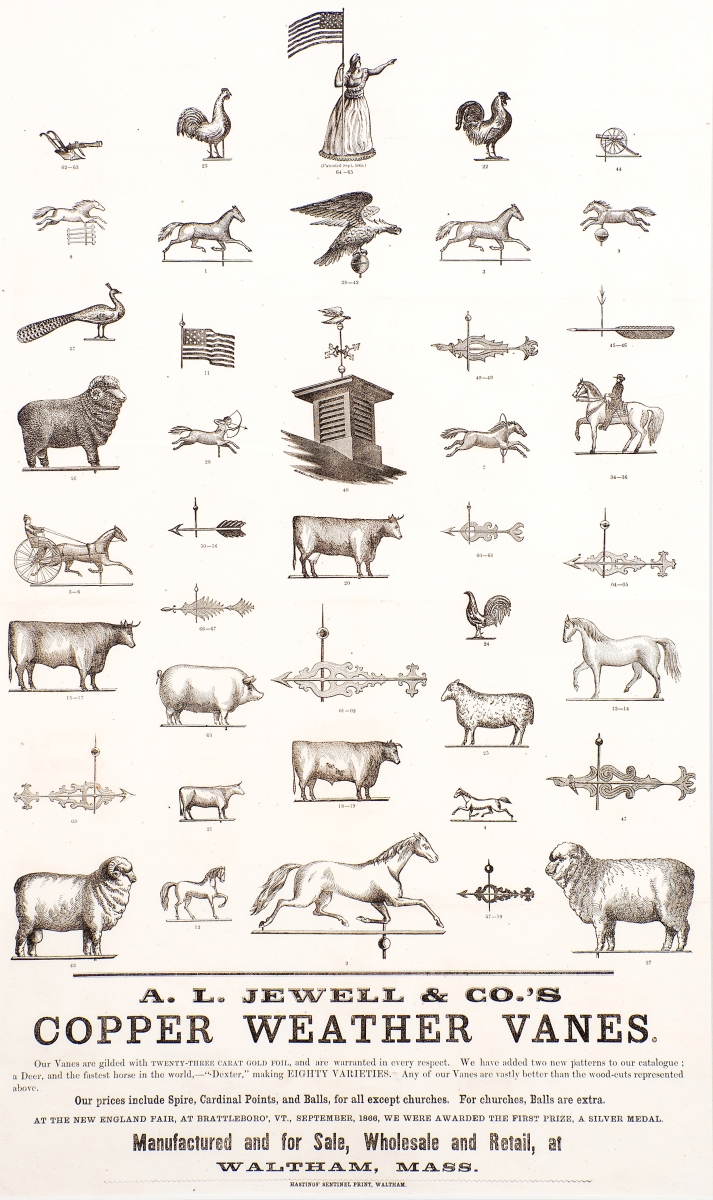

The “seminal figure in the growth of this new industry” was Jewell, who founded a metal casting and repair business in Waltham in 1852 but by the 1860s was chiefly making vanes. A “first-class entrepreneur and hero of the story,” as Shaw puts it, Jewell was one of the first manufacturers to make multiple copies of molded vanes and the first to photograph them for marketing purposes. Jewell’s vanes, primarily of molded copper and often with cast-zinc heads for extra weight, sometimes bear the die-stamped signature “A.L. Jewell & Co. Waltham, Mass.” In 1867, Jewell and an assistant died from injuries sustained in a fall while attempting to hang a wooden trade sign of their make, underscoring the danger and drama of their high-flying profession.

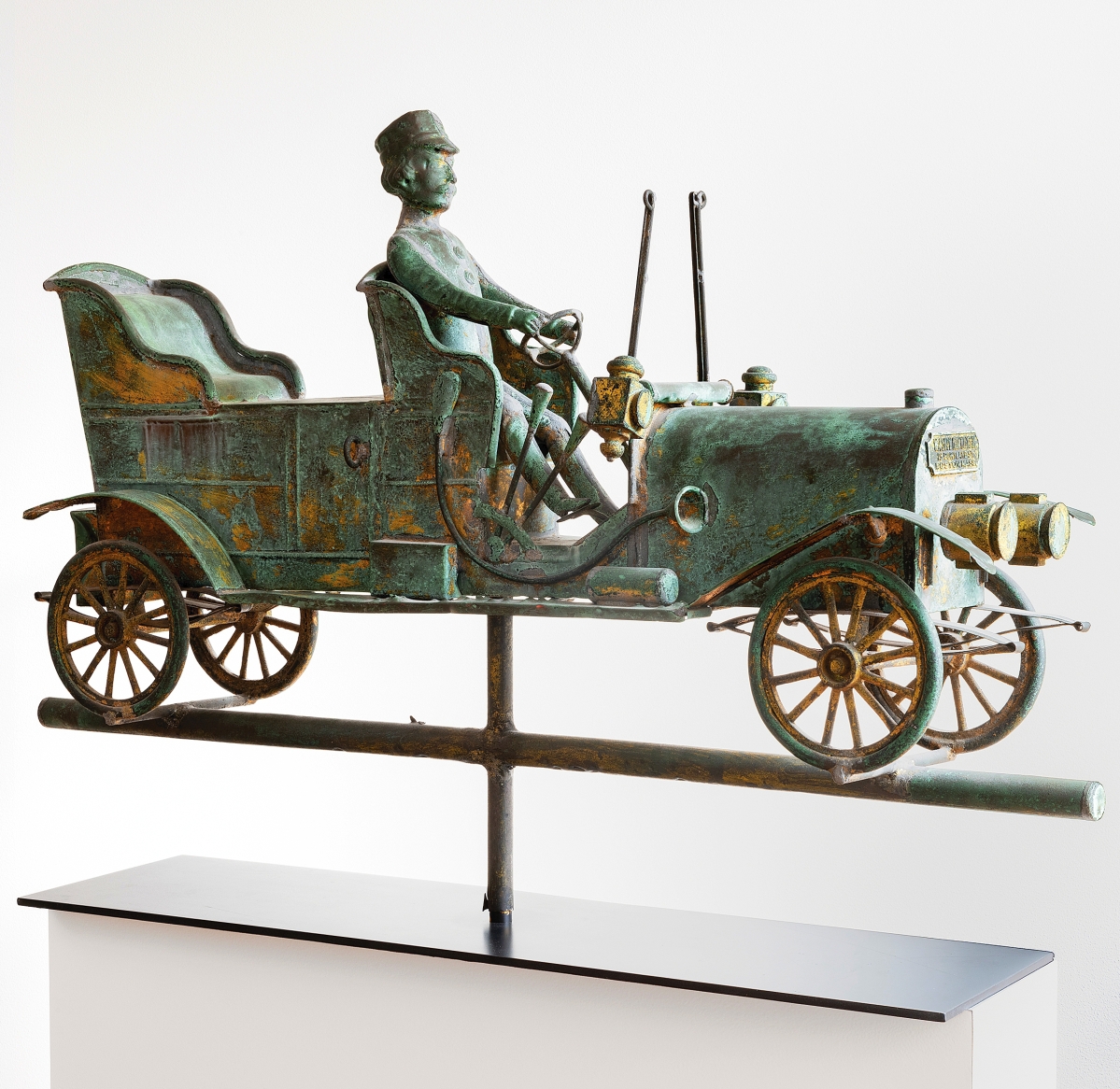

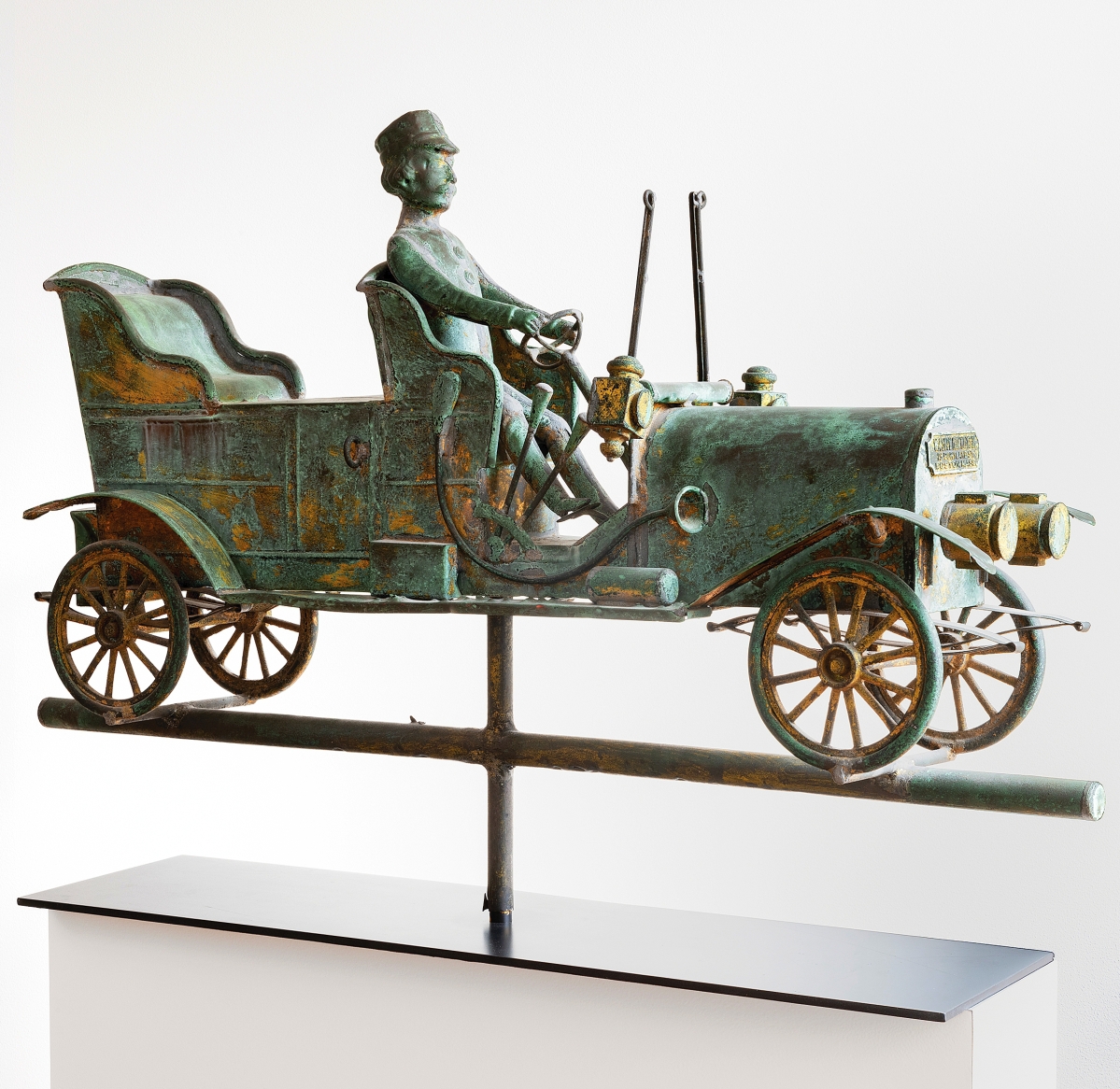

Touring car and driver, W.A. Snow Iron Works, Boston, Mass., circa 1910. Molded copper with traces of gilt, height from bottom of wheels, 18 inches, length 33 inches. Collection of Susan and Jerry Lauren, photo Adam Reich.

Jewell’s self-advertised successors were Leonard W. Cushing and Stillman White, who previously worked together in a Providence, R.I., watch factory. Using Jewell’s molds, which Cushing acquired at auction shortly after Jewell’s death, Cushing & White continued manufacturing many of their predecessor’s designs while offering new ones derived from models created by Leach. Many Cushing & White animal vanes, some of which are marked, have cast-zinc heads. After White’s departure in 1872, Cushing operated alone before being joined in business by his sons, Charles and Harry, who managed L.W. Cushing & Sons until its closure in 1933.

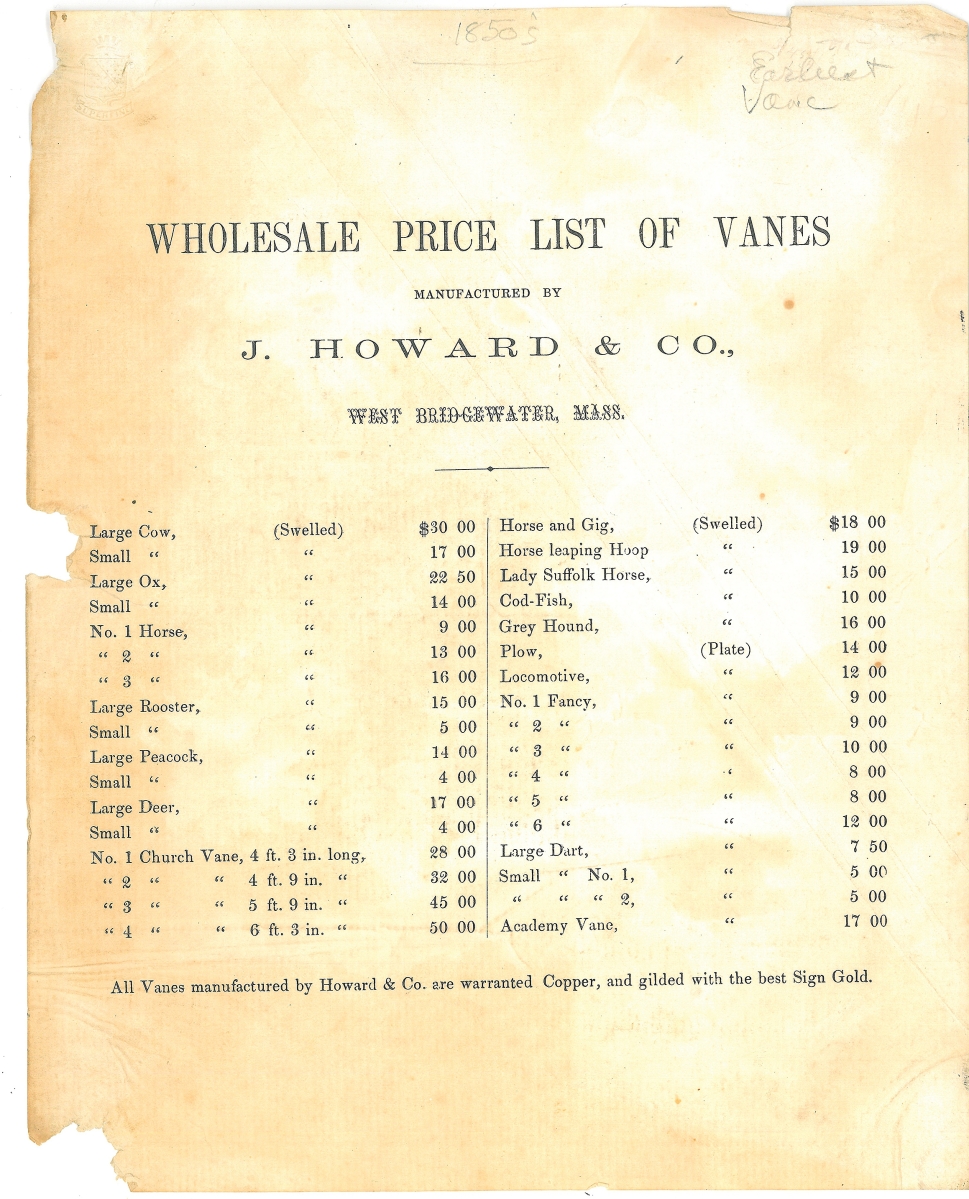

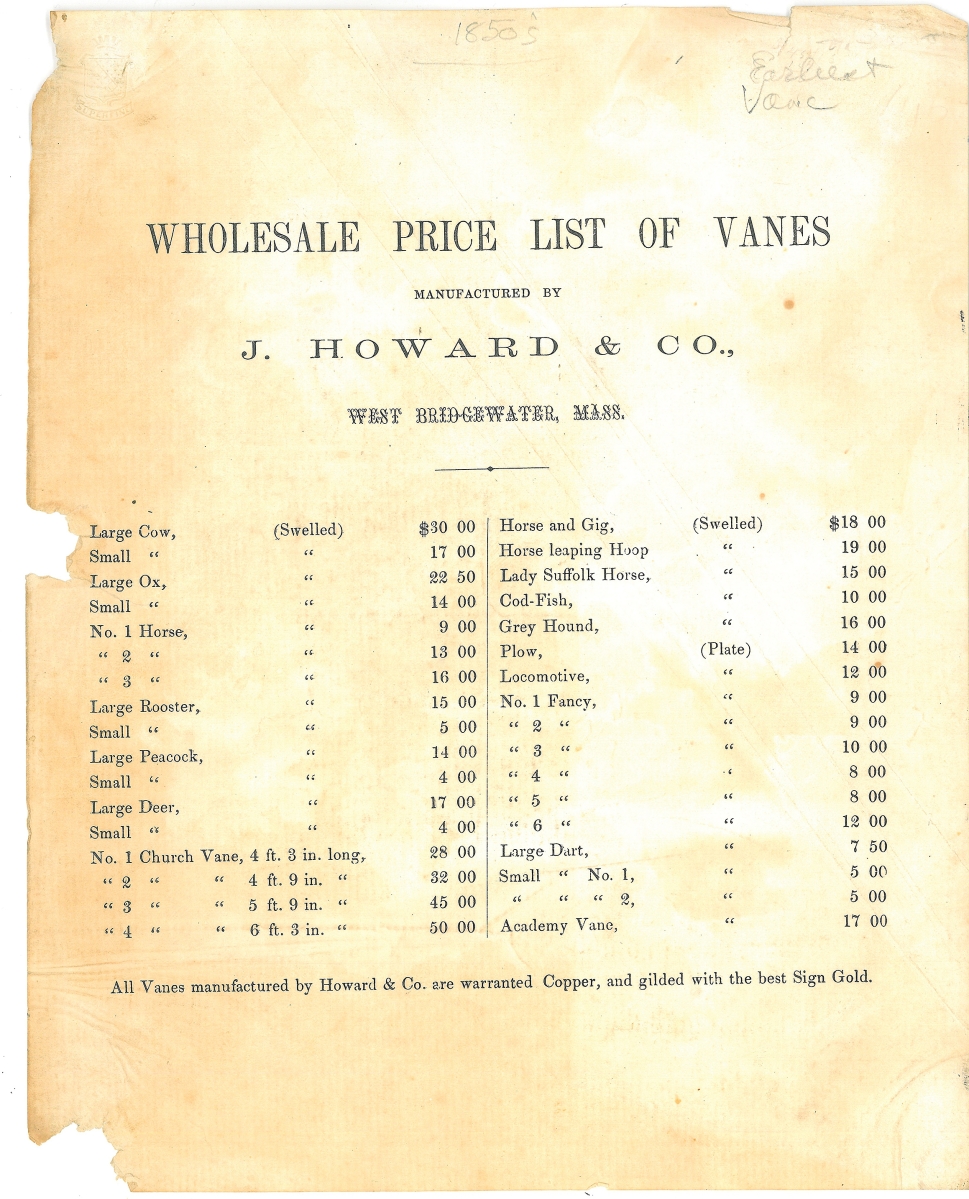

Other leading Boston manufacturers included Harris & Co; W.A. Snow & Co., which acquired Harris’s molds; and J.&C. Howard & Co., which Shaw documents to have been in business by 1850. A circa 1856 price list in the collection of Stewart Stender and Deborah Davenport indicates forms, sizes and prices of Howard vanes, but, frustratingly, is not illustrated. Some Howard vanes are stamped. All bear distinctive construction methods, including the extensive use of zinc. The much-loved Howard “Index” horse derived its name from its inclusion in the WPA’s Index of American Design in 1940.

Identifying New York-made vanes is difficult, Shaw writes. Joseph Winn Fiske (1832-1903) founded a firm specializing in ornamental iron in Boston in 1858 before opening an office and showroom in New York City in 1864. Before closing in 1982, the company gave many of its molds and miscellaneous equipment to AFAM, which in turn passed much of it along to the New York State Museum in 1990.

“The Blériot XI Monoplane,” from the Poland Spring House, Poland Spring, Me., circa 1909-14. Copper, 10 by 57¼ by 55 inches. Collection of Michael and Patricia Del Castello, photo Michael Lynberg.

Jordan Lawrence Mott (1799-1866) built an ironworks in what is now called Mott Haven in New York City’s South Bronx. After his son J.L. Mott Jr (1829-1915) became a partner in 1853, the company became known as a maker of vanes, bannerets and finials. The Mott factory moved to Trenton, N.J., in 1902.

Featuring roughly 50 weathervanes and patterns from a variety of public and private collections, plus supporting works on paper and ephemera, “American Weathervanes: The Art of the Winds” fills AFAM’s several galleries.

“Bringing together this spectacular group of objects speaks to the origins of folk art collecting and to the museum’s own history. It’s an exciting way for AFAM to celebrate its 60th anniversary,” says curator of folk art Emelie Gevalt, adding, “we are interested in the idea of weathervanes as agents of historical memory and witnesses to history.”

Two stars of the show are among works that greet visitors as they enter AFAM’s atrium. From the collection of Susan and Jerry Lauren and chosen for the cover of the book, the carved and gilded pine “Portland Rooster,” so named because it once topped a courthouse in the Maine city, is Shaw’s personal favorite. He notes, “It’s just such an extraordinarily sculptural piece, an incredible Eighteenth Century survivor and so evocative in the way its surface has weathered over time.”

“Goddess of Liberty” by A.L. Jewell & Co., Waltham, Mass., 1865-67. Molded and sheet copper, molded zinc, paint, 20 by 15 by 2½ inches, depth at base 4½ inches. Collection of Bob and Becky Alexander.

As lavish as a peacock’s tail feather is a circa 1840 banner vane made of sheet iron and blown glass for the Orono United Methodist Church in Maine. “I just love the size – it’s seven feet long – and the abstraction of the form,” says the guest curator, who gave it pride of place on the show’s title wall.

In AFAM’s North Gallery, a discussion of craftsmanship presents Leach molds alongside finished hollow-bodied vanes made from them. In the Cowin Gallery, visitors are invited to inspect the surface of vanes, including two analyzed by Dr Jennifer L. Mass, a contributor to the catalog. The examples include a molded and sheet-copper goat with yellow sizing and gold leaf, and, from AFAM’s collection, a painted sheet-metal Angel Gabriel and the more classically oxidized copper “Fame,” attributed to E.G. Washburne & Co. of New York, circa 1890.

In the capacious Fielding Gallery, visitors encounter a fantasia of vanes in all their sculptural splendor, from the Newark Museum’s great painted pine-and-iron sea dragon of circa 1830-40 to a circa 1891 witch riding a crescent moon by Ohio maker W.H. Mullins, a work now in the collection of Donna and Marvin Schwartz. A stylized paddock corrals all manner of horses, from a steeplechase jumper to a polo pony.

Small rooster by J. Howard & Co., West Bridgewater, Mass., circa 1856-67. Painted and gilded copper and cast zinc, 13 by 12½ by 3 inches. Collection of Jane and Gerald Katcher, photo Gavin Ashworth.

Shaw dates the start of the bull market for American weathervanes to Sotheby’s 1979 auction of the collection of Stewart E. Gregory, which witnessed a circa 1870 figure of a Native American with a drawn bow and arrow, now in the collection of Allan and Penny Katz, bring $25,000. On the same theme, an imposing J.L. Mott vane of circa 1900 holds the standing auction record of $5.8 million and is presently in the collection of Susan and Jerry Lauren. Shaw secured these and other record-breakers for the show.

As prices for antique American weathervanes increase, so does the need for caution when buying. Copies, some of them innocent replicas, circulate in the marketplace. Shaw writes that after locating 350 Cushing & Sons molds in a Chelsea, Mass., junkyard, Halpert in the mid-1950s made a limited number of marked reproductions, which she offered for up to $500 each.

Two final chapters of American Weathervanes: The Art of the Winds imply that a collector’s best defense against overzealous restoration and outright forgery is a thorough understanding of period weathervane construction and finishes. In her essay on the latter, Mass identifies what may be an undisturbed weathervane’s most compelling feature: its subtle patina. Weathervanes, she stresses, were traditionally not stripped prior to refinishing. Authentic surfaces consequently reflect the cumulative interaction of environment and materials over time.

Wholesale price list of vanes, J. Howard & Co., West Bridgewater, Mass., circa 1856. Unframed, 11 by 8½ inches. Collection of Stewart Stender and Deborah Davenport.

The last word on American weathervanes may never be written. Shaw acknowledges that there is more work to do on individual makers such as Isaac S. Tompkins. He would like to construct an inventory – based on a thorough analysis of catalogs, broadsides and advertisements and organized by date – of forms by maker, a project made arduous by the fact that manufacturers rarely marked their products and frequently copied one another.

Book and exhibition put before the public eye some of the most celebrated weathervanes to come to market in the past five decades. In doing so, the project honors the dealers, auctioneers, collectors and scholars who elevated this distinct genre of American sculpture.

Eager to extend the themes of the book and show into discussions of contemporary relevance, from ecocriticism, agriculture and climate to current craft practices, AFAM is planning virtual studio tours and the inaugural Elizabeth and Irwin Warren Symposium on American Folk Art. The latter, set for October 24 and called “Points of Interest: New Approaches to American Weathervanes,” will bring scholars together to discuss their latest findings and new perspectives on an evolving, multifaceted field.

In Summary

“American Weathervanes: The Art of the Winds” is on view from June 23 to January 2 at the American Folk Art Museum, 2 Lincoln Square, between 65th and 66th Street. By Robert Shaw with contributions from Jason T. Busch and Jennifer L. Mass, the companion book is published by Rizzoli Electa in association with the American Folk Art Museum. For information on both, www.folkartmuseum.org or 212-595-9533.

.jpg)

.jpg)