“La Carmencita” by William Merritt Chase (American, 1849-1916), 1890. Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Sir William Van Horne, 1906.

By James Balestrieri

NORFOLK, VA. – Art can be a pawn in the great game. That’s my takeaway from “Americans in Spain: Painting and Travel, 1820-1920,” the new exhibition co-curated and co-sponsored by the Chrysler Museum of Art and the Milwaukee Art Museum. The Great Game (often capitalized) refers to the competition among empires – British, French, Russian and Chinese – for domination over the resource-rich Indian Subcontinent and Indochina that played out from the late Eighteenth Century through the end of World War II, though some say it is still playing out today, in different ways and with different actors, including the United States.

The great game I am thinking of took place in our hemisphere. The final combatants in the game were the United States and Spain, and the prize was California, Texas and the Southwest, the Caribbean and the Philippines.

For American wanderers and artists in the Nineteenth Century, Spain offered a picturesque road, one far less-traveled than France, Italy, Germany or Britain. Its pre-industrial economy, the ruins of its past Moorish splendor, the frisson of danger from bandits and “Gypsies,” and the promise of liberated sexuality, coupled with the beauties of its landscape, made it an ideal canvas on which to project repressed fantasies.

“El Matador” by Robert Henri (American, 1865-1929), 1906. Oil on canvas. Milwaukee Art Museum, purchase, the Mr and Mrs Donald B. Abert and Barbara Abert Tooman Fund with funds in memory of Betty Croasdaile and John E. Julien.

Conversely, Spain’s “backwardness,” its apparent fall from historical greatness, and its adherence to Old World Catholicism kept the nation in its place, so to speak, in the American consciousness. Whatever Spain once had and boasted of, Spain no longer deserved. Along with its territories and sway, the great artworks of Spain made their way into the American orbit, sometimes literally, into the collections of wealthy Americans, sometimes aesthetically, as American painters sought to absorb all they could from Velásquez and other Spanish masters, absorbing in order to transcend, seeing their nascent modernity in order to craft an American modernity. Some of this is entirely innocent in intent, artists copying masters in order to learn from them. But the uses of art can be at odds with the intentions of art: that is the history half of art history, the half that this exhibition dives into in great depth.

Consider three magnificent paintings by Robert Henri. “Queen Mariana,” an 1898 copy of a Velásquez portrait in the Prado Museum in Madrid, was painted on the artist’s first trip to Spain, when Velásquez so enthralled him that he was moved to paint full-size copies. Henri wrote: “Everybody he [Velásquez] painted had dignity, from a clown to a king… He had the utmost respect for the king, the beggar and the dwarf. He painted with easy large movements, and his work has great finish combined with great looseness.” In 1898, the United States was embarking on an imperial project to “liberate” Cuba from Spain’s skeletal claws. Where Henri sees dignity and marvels at technique, what might an American audience in the jingoistic throes of empire-building (under the guise of liberation) see in “Queen Mariana?” Decadence perhaps? Excess? The antique aloofness of hereditary monarchy? The dignified Queen quickly becomes a kind of cosplay figure of fun, one that simultaneously attracts and repels.

Henri found perhaps his greatest inspiration in Spain, traveling there many times during his career, often as a leader of a group of young artists. While there, he fell in love with bullfighting and the chivalry and heraldic pageantry of the corrida, while acknowledging the violence of the sport and that, from without, it “looks like a very foolish business.”

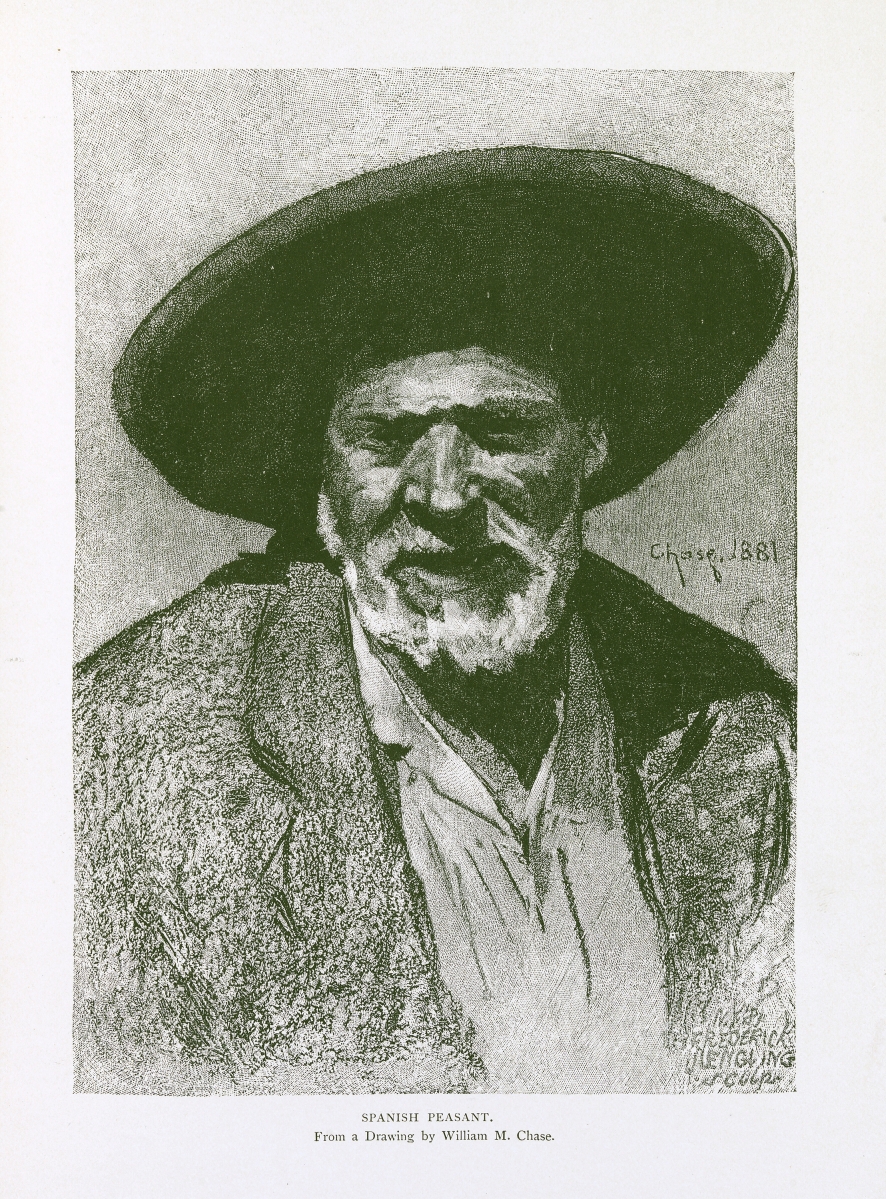

“Spanish Peasant” by Frederick Juengling (American, b Germany, 1846-1889) after William Merritt Chase (American, 1856-1925), 1881. Wood engraving in George Parsons Lathrop, Spanish Vistas, New York, Harper’s, 1883. Jean Outland Chrysler Library, Chrysler Museum of Art.

Attraction and repulsion, both are on display in one of Henri’s greatest full-length portraits, “El Matador (Felix Asiego),” painted in 1906. Henri paints the young matador as if he were a courtier of the Sixteenth Century, with a courtly, mannered bearing in a dazzling outfit. He could be about to bow and ask the viewer to dance. But that, of course, is what the bullfight is, a dance, a ritual dance – as Hemingway might have put it 20 years later – one that ends in tragedy as opposed to love – and, perhaps, doesn’t know the difference. Clearly, however, this painting, though it might owe many debts to Velásquez, represents a stylistic evolution, a style that suggests rather than depicts, a style concerned with a controlled alternation in the paint between flow and obstruction that moves the eye through and over it in serial waves and stops. We appraise and appreciate Asiego, feeling what he feels, even feeling for him, but keeping our distance, not wanting to trade places with him, not wanting to be in his shoes.

By 1916, the year Henri painted “Betalo Rubino, Dramatic Dancer,” Western Europe – excluding neutral Spain – was enmeshed in the first of two bloody World Wars. Painted in the United States, Henri “described [Betalo] as a Spanish dancer wearing a mantilla, although there is little about the costume itself that denotes it as especially Spanish.” Indeed, Betalo Rubino was a model and dancer who features in a number of Henri’s canvases in a variety of ethnic garb. What the painting projects is a stereotypical idea of Spain and of Spanish women as provocative, bold, arrogant beauties. What there is of Velásquez is completely subsumed into Henri’s own style. With new fluidity, smooth gives way to rough only for moments in the painting; what seems to be detail, on inspection, reveals itself to be bravura strokes. Whoever Betalo Rubino was, she is several layers behind this portrait of her, a portrait of a dancer who may or may not be Spanish, in a costume that looks Spanish without being Spanish. The woman, whoever she is, is unabashed about her body and beauty, and yet she is daunting, concealing as she reveals, attracting and repelling at the same time with the frank sensuality that allured Americans, a sensuality that was also taken at the time as a sign of moral – and therefore political – depravity. In this case, however, if the painting depicts an idea of Spain, it is worth considering that allure and rejection may cancel one another out, rendering the painting and its subject as neutral as Spain itself. Henri’s game, whatever it might have been to him, collapses the psychological and the political, the sexual and the imperial, into a design that sends contradictory, antipodal messages.

Rubino is an incarnation of the Spanish woman as “Carmen,” from French composer Georges Bizet’s 1875 opera of the same name, which became a standard trope of Nineteenth Century fiction, travel literature and art. Carmen, the gypsy girl from the cigarette factory, is dangerous, free and, above all, true to herself, even unto death.

“Plaza de la Merced, Ronda” by Childe Hassam (American, 1838-1920), 1910. Oil on panel. Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection on loan at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

Carmen’s proliferated on both sides of the Atlantic after Bizet’s operatic triumph. In 1890, for example, William Merritt Chase and John Singer Sargent both painted full-length portraits of Carmen Dauset Moreno, known professionally as Carmencita. Born in Malaga, Spain, in 1868, Moreno trained as a dancer and became a sensation throughout Europe and in the United States.

Looking at the two paintings, Sargent’s contrapposto portrait with arms akimbo descends to Henri’s “Betalo Rubino,” but Chase captures the dancer in action, her head thrown back in a smile directed in part at the audience and in part at the joy in her own performance. Ribbons fly, castanets click, roses land at her feet. Though I suppose Sargent’s picture would be considered more accomplished, capturing a certain powerful and haughty stillness in the dancer, Chase’s “Carmencita” is more self-sufficient, performing for us, yes, but also for herself.

But what happens when we take the male gaze away altogether? What happens when male conquest, whether it is imperial or romantic, or frankly sexual, no longer obtains? What happens when “Carmen” is painted by a woman, an ardent feminist like Mary Cassatt? “Spanish Girl Leaning on a Window” was painted circa 1872 when the artist traveled to Spain, spending much of her time in Seville. With her hands and arms painted with a splendid High Renaissance roundness and her elbow sticking out into the sun, into the viewer’s space, Cassatt’s “Spanish Girl” is entirely enigmatic, taking you in even as you take her in, questioning in the moment before any actual question forms. Indifference? No. Mild curiosity? Maybe. Dignity? Absolutely. Half in shadow, half in light, her eyes and mouth may break into a smile – or not. You are part of the passing show. No more, no less.

“My Uncle Daniel and his Family” by Ignacio Zuloaga y Zabaleta (Spanish, 1870-1945), 1910. Oil on canvas. Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Caroline Louisa Williams French Fund.

It’s no accident that after World War I reset the bar for battlefield horror, artists turned away – somewhat – from Velásquez’s formal cryptography, finding inspiration to Goya’s haunting images and in the Spanish city of Toledo, where El Greco’s pallid, elongated and contorted figures suited the raw, anxious, withered mood of the times.

By the mid-1930s, just 15 years after the period covered by the exhibition ends, Spain becomes part of another great game, this time with Europe as the stakes, and, perhaps, the world. I am referring here to the Spanish Civil War and the rise of fascism under General Francisco Franco, whose shadow would loom, unbelievably, over the nation until his death in 1975. American and European artists raced to Spain to fight fascism. Sculptor Jo Davidson, who would go on to sculpt Franklin Delano Roosevelt and many other political leaders of the day, traveled to the front and brought back works that were intended to warn Americans of the coming war against fascism.

Different pawn, different game.

After World War II, American artists such as Clark Hulings continued to visit and paint in Spain, seeing the nation with new empathy, as a resilient land with a long, storied past and a people who carried on in their daily lives with dignity despite dictatorial rule.

“Segovia” by Ernest Lawson (American, 1873-1939), circa 1916. Oil on canvas. Minneapolis Institute of Arts, The John R. Van Derlip Fund. Photo: Minneapolis Institute of Art.

Could it be that there’s always a great game of one sort or another, and that art is destined to play a part, wittingly or unwittingly, in that game? Artists are in and of their times, but aren’t they supposed to, in some measure, be above and outside them, exposing the discourses that shape us invisibly, so that we might know better and do better? That might be the greatest game of all, and the greatest challenge.

I must end with a fast shout-out to my niece Beret Balestrieri Kohn, the Audio Visual Librarian at the Milwaukee Art Museum, who has worked there since she was in her teens, and whose invaluable work is of great benefit to the museum and to me whenever I need someone who knows the way through the labyrinthine storehouses of images of art.

“Americans in Spain: Painting and Travel, 1820-1920” continues at the Chrysler through May 16. The Chrysler Museum of Art is at 1 Memorial Place. For information, www.chrysler.org or 757-664-6200.