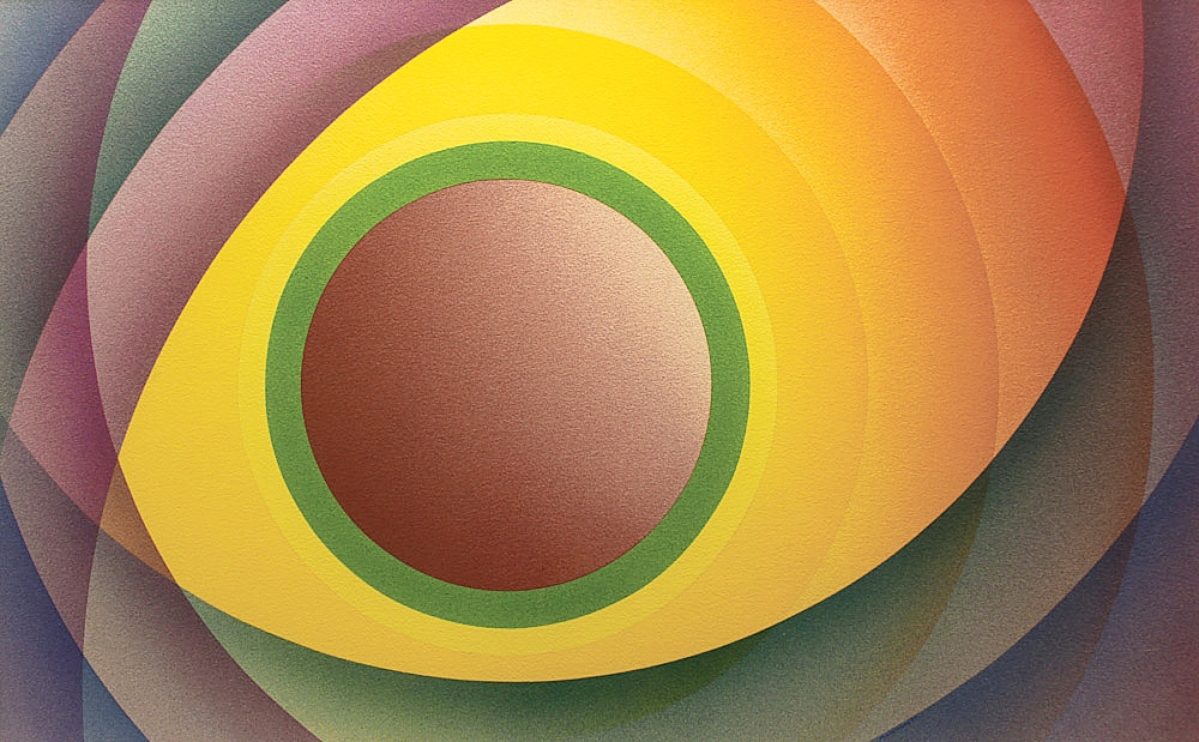

“Casein Tempera No. 1” by Raymond Jonson, 1939. Casein on canvas, 22 by 35 inches. Albuquerque Museum, gift of Rose Silva and Evelyn Gutierrez, PC1999.85.1.

By James D Balestrieri

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. – Expression conceals as it reveals. To say art secretes meaning is to say the word “secrete” in its binary, antipodal meanings: secrete as discharge, release; and secrete as conceal, veil. Vibrations hide inside the geometry of the works by members of the Transcendental Painting Group, inside the Raymond Jonsons, Lawren Harrises, Emil Bisttrams, Agnes Peltons and all the rest, inside their concentric ellipses and polygons and fields of color. You want to unlock and hear those vibrations but their music is as elusive – perhaps deliberately – as the music made by ripples on a placid pond. “Another World: The Transcendental Painting Group,” the new exhibition at Albuquerque Museum, offers a comprehensive look at these understudied artists and their art.

Raymond Jonson’s 1939 painting, “Casein Tempera No. 1,” is an excellent example and a good place to start this discussion. The shaded circle, just left of center, is a circle, a sphere, a hole, an eye, a porthole, a portal. It can be negative, like a hole, or positive, like a sphere. This object sits in concentric circles overlaid by a series of eccentric rotations. You can imagine the whole as a cosmic machine, the clockwork of a solar system. Your eye moves around it, over it, through it. Individually, the tones – I am speaking of both color and sound – are different, often very different, from one another; in combination, they harmonize. Overall, the effect is a kind of wandering restfulness.

It’s amazing how often you find that a short-lived movement in art has a longer shelf life than anyone in the movement could ever have imagined. The Transcendental Painting Group (TPG) formed in 1938 and disbanded just three years later in 1941, in large measure because of the exigencies of World War II.

Installation image, “Another World: The Transcendental Painting Group” at Albuquerque Museum. Photo Nora Vanesky.

In the unending, alternately hot and cold, but ultimately phony war between realism and abstraction, the Depression fostered strong interest in representational art and the Social Realism characteristic of the WPA artists. In his essay for the catalog, “The Transcendental Painting Group and Significant Abstraction,” Scott A. Shields writes, “As the TPG manifesto made clear, the group did not share the prevailing concern with ‘political, economic or other social problems.’ Jonson, for one, sought consciously to work against the grain: ‘I am not interested in telling the farmer and politician about our country but rather in telling all about the wonders of a richer and deeper land – the world of peace – love and human relations projected through pure form.'” In other words, the concern of the TPG was for the spiritual health and well-being of all the people on the planet as opposed to the material needs of the impoverished and the failures of established political and economic systems to grapple with inequities. Like the realism of the period, the TPG saw an absence, and a need, but chose abstraction, not in the Modernist search for pure form – art for art’s sake – but in search of artistic forms that would elicit responses, responses that, in turn, would contribute to human harmony.

Thinking about the Taos Society of Artists and Los Cinco Pintores in Santa Fe, about J.H. Sharp and Ernest Blumenschein, Fremont Ellis, Georgia O’Keeffe, and dozens of other painters, the TPG brand of abstraction must have had a hard time in New Mexico. Like most artists, the TPG painters generally started out in the realm of realism. The Canadian painter Lawren Harris, for example, made his name painting landscapes that recall Rockwell Kent’s work – mountains, skies, ice, water – in simplified realistic forms, yet his desire to venture beyond that, to transcend it, if you will, is evident in his 1939 canvas, “Painting No. 4.”

There are asymmetrical mountain forms – one gray, one turquoise – that spill off the left and right edges of the painting, but the white diamond dominates the space and contains the lavender, blue and purple diamonds that vibrate and overlap inside it. It is as if mountains might emerge from these Platonic Forms of mountains, as if a single sun might form from the two at center and left and the parts of a sun that are gathering themselves at right. Together, the three are like shields with insignia, guardians of the natural world and natural law. Harris is after the mountain before the mountain, the symmetries that emerge into reality and are worn and transformed by time. There’s more. All of this is superimposed, as it were, on something we can’t see apart from monochromatic arcs at the bottom of the canvas. Forms beneath Forms beneath Forms; like the parable of the turtles, it is Forms all the way down, though the more we look at them, the more we see that they are not archetypes, that their symbolism is Harris’, expressed for us, if we want it.

Wassily Kandinsky is the driving force, the soul, if you will, of the TPG. His search for a conscious spiritual art – one not dependent on surrealism’s dreams, instinct and intuitions – guides Jonson, Bisttram and the rest of the TPG. Kandinsky said, “We have before us the age of conscious creation with which the spiritual in painting will be allied organically; with the gradual forming structure of the new spiritual realm, as this spirit is the soul of this epoch of great spirituality.” In 1910, when he wrote On the Spiritual in Art, quoted above, the world, to Kandinsky, might have looked to be on the verge of transformation. By August 1914, it was, though the transformation was not at all what Kandinsky predicted. Had he written his book in 1915, that last quote might have been very different.

Conscious spirituality rejects surrealism but also repudiates the Emersonian idea of Transcendentalism, with its return to and reliance on natural forms as a path to spirituality. For the TPG, an awakened rationality and a fearlessness is the source of creation – there is no turning back to nature or to earlier forms of art.

The TPG’s true champion and philosopher, Dane Rudhyar, in his unpublished book-length study, The Transcendental Movement in Painting (excerpts of which are published in the catalog for the first time) makes the case for the TPG knowing that the world is on the brink of the century’s second world war. Rudhyar wrote: “Let us be more brutally frank: the issue today for America is between Transcendentalism and some form of Fascism; between a Walt Whitman and a Mussolini; between a life of creative freedom in the realm of ideas and universal symbols, and a life of subservience to some collective pattern of thought and behavior imposed upon masses too frantic with insecurity and too emotional to resist the hysteria aroused by radio voices, by the modern ‘black magic’ of dictatorships and organized greed.”

“Composition #57/Pattern 29” by Robert Gribbroek, 1938. Oil on canvas, 36 by 27 inches. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, The Harriet and Maurice Gregg Collection of American Abstract Art 2019.42.

For Rudhyar, the TPG was necessary, an antidote for the above, summed up in this way: “The purpose of the Transcendental Movement which can become the keynote of our century is to arouse men and women out of their bondage to sense-patterns and dead intellectual attitudes; to stir in each and all the creative spark, the ‘Living God,’ whose essence is fire, audacity, heroic activity, search for ever wider meanings; whose rhythm is one of cyclic metamorphoses leading ever-onward along the spiral of ever-progressing, ever more transcendent living.”

The radiance that the TPG strove for didn’t stop World War II. Radiance twisted into radiation that fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, proving that we could make the fabric of nature do our destructive bidding. War is the opposite of art.

Still, look again at the works on these pages. TPG paintings often look as though they correlate to some phenomenon – as though they might be scientific diagrams or visualizations of experiments with light or sound, or that they represent the infinite or the infinitesimal – or that they sprang from science and then metamorphosed into something more, something neurological and metaphysical. Agnes Pelton’s 1930 painting, “The Voice,” for example, is an attempt to visualize song, speech, utterance. Under her brush, the voice becomes something vegetative, something growing and reaching up, something alive. Similarly, Emil Bisttram’s “Creative Forces” is like the spectrum of a comet seen through a prismatic instrument.

.jpg)

“Creative Forces” by Emil Bisttram, 1936. Oil on canvas, 36 by 27 inches. Private collection, Courtesy Aaron Payne Fine Art, Santa Fe.

If there’s a time and place for everything, 2021 might be the year for the Transcendental Painting Group. Artworks that convey spirituality unmoored from organized religion while blending mysticism and meditation, that seem to possess a personal, sacred geometry, while sharing in the Midcentury Modern appeal of Bauhaus and Art Deco, the atomic age and the jet age – with all the connotations of a better tomorrow that may or may not come to pass – might just be what the universe ordered.

In the phony war between realism and abstraction, realism often takes hold of the artistic zeitgeist at times when we need to be reminded of our common humanity; abstraction, on the other hand, often rises to the surface when it seems as though our inner lives need shoring up. Shields notes, “In the United States, work by the TPG bore some relationship to the Synchromism of Stanton MacDonald-Wright and Morgan Russell, these artists, like Kandinsky, finding commonalities between abstract painting and music… The reductive, streamlined Precisionism of Charles Sheeler and Charles Demuth also held aesthetic motivation for some in the TPG, Jonson most notably, as did the paintings of Joseph Stella and the design forms of the machine age.” Reconciling machines and our species that makes those machines, marrying senses to sciences and making art of these syntheses is one of the philosophical projects of Twentieth Century art, a project very much on the minds of artists today.

Abstraction and realism. It’s all isms, choices, human expressions that reveal as they conceal. The phony war between realism and abstraction is a war that was never a war. There are wars enough without it.

The exhibition is on view at the Albuquerque Museum through September 26. The show travels to the Philbrook Museum of Art from October 17, 2021 to February 20, 2022 and then to Artis-Naples, the Baker Museum, from March 26 to July 24, 2022. The show will then travel to the Crocker Art Museum from August 28 to November 20, 2022 and it will conclude at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art with a run from December 18, 2022 to April 16, 2023.

Albuquerque Museum is at 2000 Mountain Road NW. For more information, visit www.albuquerquemuseum.org or call 505-243-7255.