“Transparency of the Moon from Negatives Made at the Lick Observatory, Mount Hamilton, California,” circa 1896. Gelatin silver transparency on glass, overall 18-11/16 by 15¾ inches. Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

By James D. Balestrieri

NEW YORK CITY – When a mystery loses its mystery, when something we have seen as beyond human understanding is brought, through science, into what Nathaniel Hawthorne called the “realm of ordinary experience,” we reclassify it, place it among the things that used to amaze us, but no longer do, at least not in the same way. Old gods. Chimerical beasts. Superstitions. H.G. Wells’ Selenites, from his novel First Men in the Moon, no longer live beneath the lunar surface. The Maria – seas in Latin – that we imagined there turned out to be vast plains of dark basalt. The tides that the moon makes became the measurable consequences of gravity. The full moon, as it turned out, didn’t turn us into werewolves or drive us mad. Lunacy is a word with a history, an etymology rooted in myth, not a diagnosis.

Then, on July 20, 1969, NASA astronaut Neil Armstrong stepped down from the Lunar Lander and placed the first human footprint on a body in our solar system other than Earth. By rights, the moon should have released much if not all of her strange hold over us. And yet, as “Apollo’s Muse: The Moon in the Age of Photography,” the new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art – designed to coincide with the 50th anniversary of NASA’s historic moment – demonstrates, the moon, despite the revelation of many of her secrets, remains a source of wonder. Indeed, it might even be said that the knowledge we have acquired about the moon has only created fodder for new and even, perhaps, greater flights of fancy. Moonlight still beguiles.

As with every modern artistic medium, photography, from the get go, moved in two directions: scientific and aesthetic. The exhibition features a number of gorgeous, accurate drawings of the lunar surface as revealed in telescopes that seemed to improve with every passing year, but photography offered new opportunities to record and share observations with something approaching absolute fidelity. In the fine catalog that accompanies the exhibition, with essays by curators Mia Fineman and Beth Saunders, and with an introduction by Tom Hanks, Saunders describes the state of science at the outset of the Nineteenth Century, privileging vision above the other senses, “The camera and other optical devices such as the telescope functioned as extensions of the eye, making possible study of phenomena hitherto beyond the reach of human vision. In a sense, images became more important than ever before, and photographs offered an unsurpassed verisimilitude, providing the raw visual data on which science was based.” But the daguerreotype, the most advanced photographic process of the time, required chemically prepared plates and long, light-gathering exposure times. The moon moved. Telescopes had to be equipped with clockworks to keep her centered in the eyepiece long enough to get a clear, very small picture. A cellphone camera held up to a telescope is infinitely better but still not that great. And the daguerreotype made only a single image. Challenging.

By the 1850s, as telescopes and cameras improved, the moon’s mysteries revealed themselves. This is evident in a pair of images by John Adams Whipple, both photographed through the Great Refractor, a 15-inch telescope at Harvard University. One is a daguerreotype taken in 1852, the other a paper print from a glass negative executed with his partner James Wallace Black in 1857-60.

In the daguerreotype, we see all the limitations of the young medium: an inability to capture detail, the deterioration of the chemically treated metal surface, the sheer smallness of the image. And yet, at this remove, some 170 years in the future, the yearning for scientific accuracy has, through some alchemy, transformed the photograph into an aesthetic object with all the pleasurable wrongness of space travel as silent film, radio drama and early television conceived it. The 1857-60 paper print, by contrast, despite its resemblance to the moon as seen and drawn through the telescope, is not without its own steampunk charm. This is the moon as Verne and Wells would write about it. Science fiction, but drawn from science.

By 1896, the year that “Transparency of the Moon from Negatives Made at the Lick Observatory, Mount Hamilton, California” was produced in preparation for a lunar atlas, photographs of the moon had achieved a level of sophistication and detail that would not be surpassed until the advent of spacecraft-based cameras. Shadows in craters and radiating impact cracks allowed astronomers to measure features of the surface and to delve into the geological formation and composition of the moon.

“View of the Moon” by John Adams Whipple, (American, 1822–1891),1852. Daguerreotype, 3⅞ by 3 inches. John G. Wolbach Library, Harvard College Observatory, Cambridge, Mass.

At about this same time, the first motion pictures appeared. One of the pioneers of cinema, Georges Méliés, turned his sense of invention and fantasy moonward in 1902. A Trip to the Moon (Le Voyage dans la lune) returns our nearest neighbor to the realm of romance as the top hat and tails clad astronauts hurl themselves to the moon in a hollow shell shot from an enormous cannon. The man in the moon blinks and winces when their spaceshot punctures his crusty cheek and the dapper astronauts fight monsters and dally with a race of butterfly women among giant fields of moon mushrooms. If you’ve never seen it, give yourself a 15-minute treat: the film is long out of copyright and free to view on YouTube.

Two years later, Edward Steichen’s, “The Pond – Moonrise,” poeticizes not the moon itself, but the effects of its soft, cold light through a stand of spindly trees beside a still pond. This is a moon for creatures we humans venerate and mythologize – owls, wolves, bats, loons – a moon for seeing just enough without being easily seen, a lovers’ moon.

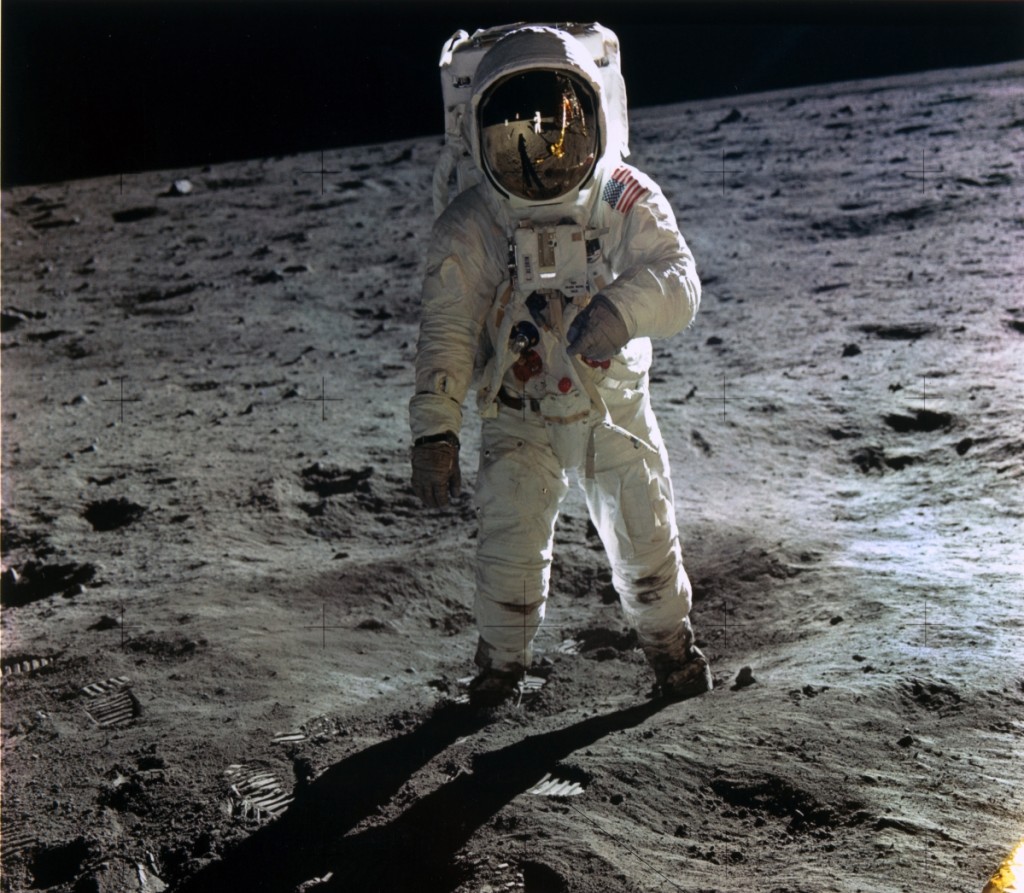

After World War II, when a Cold War and a hot Space Race found the United States and Soviet Union in constant competition, rocket ships and astronauts began to appear in popular and high culture, even in couture, as in Harry Gordon’s whimsical and slyly sexual “Rocket Dress,” but when the Apollo program ended and we turned our attention to the space shuttle, the International Space Station, Mars, and elsewhere, our scientific interest in the moon waned. Jojakim Cortis and Adrian Sonderegger’s 2014 photograph “Making of AS11-40-5878 (by Edwin Aldrin, 1969)” spoofs those who assert that the moon landings were faked, possibly in Hollywood under Stanley Kubrick’s direction.

In the artists’ retelling of Aldrin’s famous photograph, “a square pile of gray dust bears the recognizable mark of a boot print left on the lunar surface. Strewn around that familiar composition, however, are paintbrushes, a saw, bags of cement and a print of Aldrin’s original photograph. Cortis and Sonderegger’s work calls attention to the way certain images form a collective cultural experience.” Casting a satirical, feminist eye on the moonshots, Aleksandra Mir’s “First Woman on the Moon, 1999” recreates the Armstrong moment on a beach with five women, highlighting the fact that no woman has set foot on the moon, though it is often personified as a female force beside the sun’s vital and unapproachable light, which is personified as unchangingly male. This is an image that Georges Méliés would love.

Now that we are talking again about returning to the moon, establishing ourselves in bases there, using it as a low gravity jumping off point for missions to Mars and beyond, the moon may be poised for a new moment. But when I think of the moon, my mind moves in two directions. First, to my daughter’s 6-inch Newtonian reflector telescope which reveals to us the mountains, craters and plains of our pockmarked, long-suffering satellite in detail unimaginable to Galileo and his descendants. And then to the black shields of the 900 Thespians at the Battle of Thermopylae, adorned as scholars believe they were with quarter moons pointing upwards like smiles, the Thespians standing side by side with the far more famous 300 Spartans against the Persian host, the Thespians, yin to the Spartans’ yang, moon beside sun, lesser light beside greater. Did the Persians see those moons as moons, smiles or something else – abstract boats to ferry souls, perhaps?

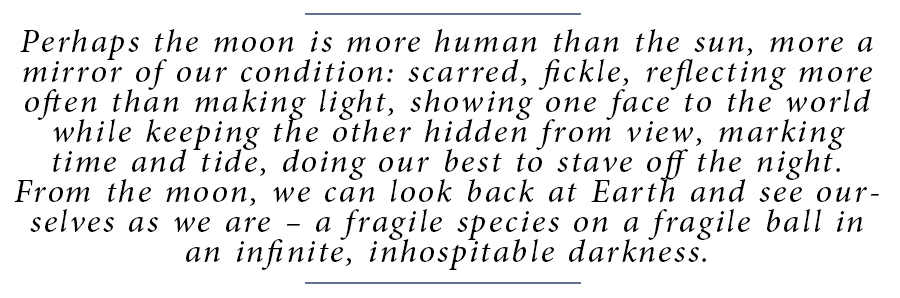

“Buzz Aldrin Walking on the Surface of the Moon near a Leg of the Lunar Module” by Neil Armstrong (American, 1930–2012), NASA Apollo 11, 1969, printed later. Dye transfer print, 16-1/8 by 16-3/8 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Alfred Stieglitz Society Gifts, 2017.

Each month, the moon reveals and conceals herself, and perhaps it is this oscillation between revelation and concealment that makes the moon simultaneously an object of scientific curiosity and aesthetic, romantic wonder. Perhaps the moon is more human than the sun, more a mirror of our condition: scarred, fickle, reflecting more often than making light, showing one face to the world while keeping the other hidden from view, marking time and tide, doing our best to stave off the night. From the moon, we can look back at Earth and see ourselves as we are – a fragile species on a fragile ball in an infinite, inhospitable darkness.

Apollo 17 astronaut Harrison Schmitt captures the beauty and complexity of our home planet, as well as its singular loneliness in his 1972 photograph, “Blue Marble.” While storm systems swirl over the Southern and Indian Ocean, desert dominates North Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Einstein may have been right when he said, “God does not play dice with the universe,” but here the Earth looks like a glass aggie that might be knocked out of the string ring at any moment.

In the 1950s standard “Destination Moon,” Dinah Washington sings, “Travel fast as light ’til we’re lost from sight/The earth is like a toy balloon/What a thrill you’ll get ridin’ on a jet/Destination Moon.” The future then was a hopeful place where technology would free us not only from drudgery, but from gravity itself. The universe was our bed of oysters and the moon was just the first pearl. Here on earth, now, the beds of oysters are in peril. In space, the beds of oysters, ones that resemble ours, anyway, are light years away, if they exist at all. But the moon is still the first pearl.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is at 1000 Fifth Avenue. For information, www.metmuseum.org or 800-662-3397.

_1999.jpg)

_2014.jpg)