Coco and Arie Kopelman, June 2015. The New Yorkers look forward to spending more time at their seasonal residences in Nantucket and Indian Wells, near Palm Springs.

By Laura Beach

NEW YORK CITY – If you could tell a book by its cover, might it also be possible to know Arie L. Kopelman by what he collects? After wangling a lunch invitation with the Winter Antiques Show’s departing chairman, I put the proposition to the test.

Kopelman, here with former Winter Antiques Show exhibitors Fred and Kathryn Giampietro, collects American folk art.

The newly named chairman emeritus of America’s best-loved fair recently handed over daily responsibility for the charity event to Lucinda C. Ballard and Michael R. Lynch, fellow members of East Side House Settlement’s board of managers. At the show’s helm since 1995, Kopelman restored peace and plenty to what had for a time been a troubled operation, giving it polish, sophistication and a worldly air. He brought unsurpassed personal and professional qualities to the job: global marketing savoir faire honed as president of Chanel Inc, and, before that, as vice chairman and general manager of the creative advertising shop Doyle Dane Bernbach; a glittering array of personal connections; and an eye for style married with confidence, charisma and, not least, humor.

As writer Jill Kargman, who inherited her father’s satirical gift, explained in Sometimes I Feel Like A Nut, “My dad did stand-up comedy to put himself through business school and he instilled in us a value system based on good times and cackles aplenty.”

“I’m a happy guy. I like to smile and have a good time,” Kopelman tells me, naming Winter Antiques Show exhibitor Arthur Liverant as a conspirator in the jokes department.

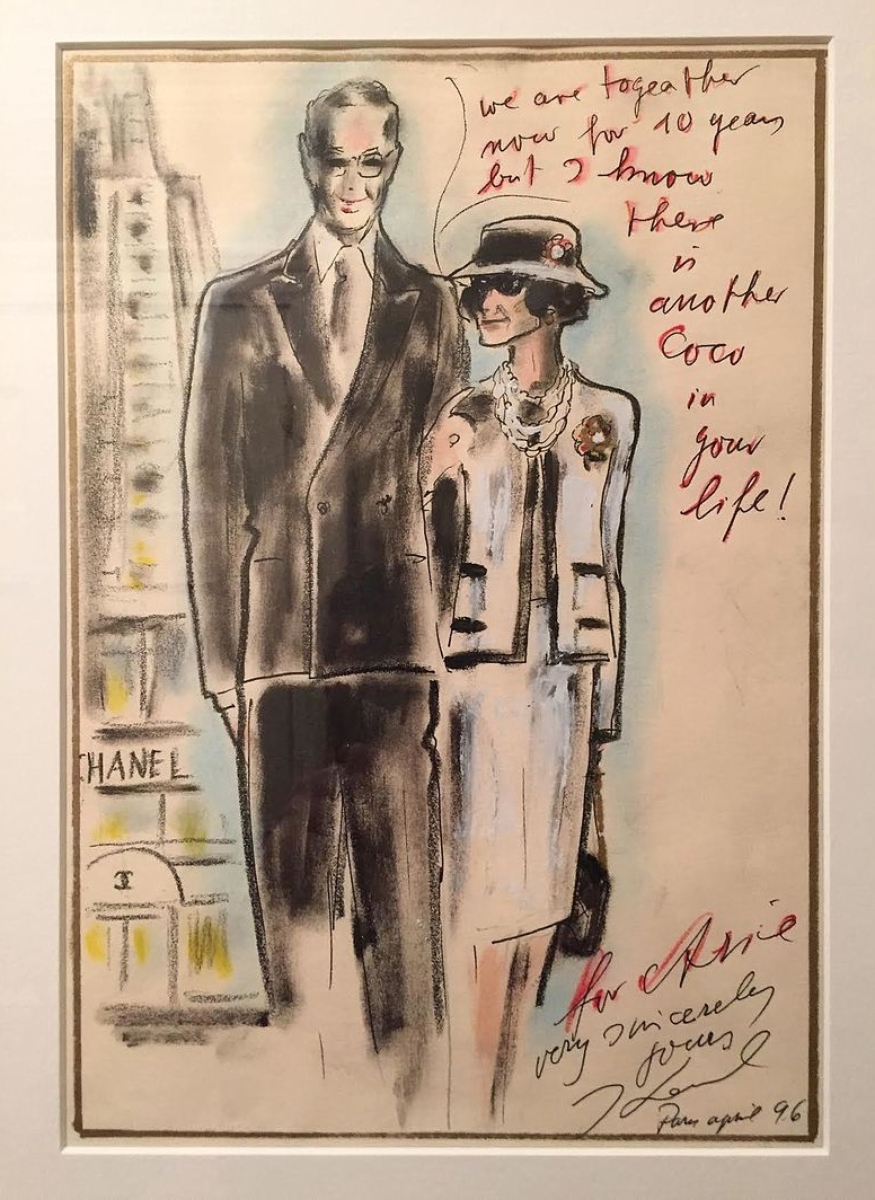

Chatting with exhibitors during setup and welcoming guests on opening night, his lovely wife, Coco, at his side, Kopelman has been an ebullient presence at the fair. It was not until I spent time with him that I saw what the Winter Antiques Show has given him in return.

Two stories about Kopelman are revealing. Once, I happened upon the devoted husband, father and grandfather at Christie’s, where he had come to bid on a quill weathervane, intended as a gift for Jill. Another time, learning that I had visited the Chinese export porcelain dealer Elinor Gordon in Pennsylvania, he inquired if I had seen tea caddies he might like. Mind you, only specimens in silver mounts would do.

Kopelman is from Brookline, Mass., the son of a Harvard-schooled lawyer and judge. “I’m a Boston boy and it resonates for me in every way that is meaningful,” he says, showing me a Nineteenth Century painting by a Boston miniaturist that hangs in the entrance of his New York apartment, a few doors down from the Park Avenue Armory. The work depicts a fire in Chelsea, across the Mystic River from Boston.

_fotor-809x1024.jpg)

East Side House Settlement is awarding Kopelman its first Heart in Hand Award for public service. The name is in part inspired by Kopelman’s collection of heart-decorated objects, including this heart-in-hand love token from Old Hope Antiques. Photo courtesy Olde Hope Antiques.

Educated at the Boston Latin School and Williston Academy, Kopelman attended Johns Hopkins University before earning a master’s degree in business administration at Columbia University. A job at Procter & Gamble, once a rite of passage for classically trained marketing men such as himself, sent Kopelman on his way. In the mid-Eighties, he hopped from advertising to the client side when he joined Chanel, where, as president, he helped build the luxury goods company into a $7 billion operation.

“I used to love going in and out of all the little antiques shops on Second Avenue,” Kopelman tells me over a meal of herring in cream sauce with rye toast at Donohue’s Steak House, a Lexington Avenue haunt of East Side House dealers, among them the late “King of Ming,” Robert H. Ellsworth, who is said to have dined there daily and to have left his favorite waitress and her niece $50,000 each upon his death in 2014.

Kopelman likewise enjoyed the Winter Antiques Show. Committed to improving educational opportunities for disadvantaged youth, he joined the board of East Side House Settlement in 1982 and by 1986 had a place on the Winter Antiques Show Committee under chairman Mario Buatta. Coaxed into the role by East Side House trustee Louis W. Bowen, with whom he shared the top spot in 1995, Kopelman became the show’s chairman in 1996. Acknowledging his desire to retire, Bowen explained at the time, “I was 80 this past December, and the Winter Antiques Show is 41 years old. We’ve seen a lot of one another.”

Despite a hectic travel schedule, including a monthly commute to Paris, Kopelman made it all work. He recalls, “The first thing I did was create a dealers committee. Without dealers, there is no show. I wanted to be a listener. I came from an operational kind of background, so I could bring some discipline strategically and executionally to the party. I wanted to market the show with more advertising and figure out who the corporate sponsors were so there was enough money to have a substantial ad game. I knew how to put together dealers who would energize the whole, make it more than the sum of the parts. Of course, I had great people helping me.”

Liberated from professional obligations, the Kopelmans aim to spend roughly half the year in history-rich enclaves in Nantucket and Indian Wells, Calif., near Palm Springs. Their New York residence is a prewar apartment tweaked by society decorator Mark Hampton not long after they moved in 25 years ago.

Hampton’s traditional, faintly Anglophile approach has weathered well. “Mark’s genius was helping us with backgrounds. We put a highly eclectic collection of fine and decorative arts into the harmonious rooms he created,” Kopelman explains. He once contemplated a business partnership with the late designer, whom he considered a good friend. “I thought of buying a bunch of specialty design companies and putting them under one umbrella. It never happened. I told Ellie Cullman, also a friend, to hire me when I retire. I’m a frustrated decorator and a good little picker.”

Hampton’s touch is perhaps most evident in the formal dining room, where the couple settled on a hand painted wallpaper from Gracie. Its exotic flourishes and subtle palette call to mind the Chinese Parlor at Winterthur. The breche d’Alep marble mantel with exquisitely carved shell came from Asta on Second Avenue. Elsewhere, a Seventeenth Century Dutch painting of oysters spilling out of a barrel summons memories of the European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht. A bottle carrier from Apter-Fredericks is one Kopelman first saw at London’s old Grosvenor House fair.

Kopelman, right, with Michael R. Lynch and Lucinda C. Ballard, co-chairs of the 2018 Winter Antiques Show.

“If Coco had a family crest, it would be hands rampant. On one side it would say, what do we need it for? On the other side, where are you going to put it?” Kopelman says, affectionately describing a common marital malady. “I’m the lunatic who sees things, loves them and doesn’t ask questions because I figure I’ll find a spot.”

Kopelman’s vision for the Winter Antiques Show parallels his personal theory of collecting. “Mixing great things of various periods makes a much more exciting decorative statement. To me, life is a scrapbook of memories, what has happened over the course of nearly 50 years of living with one person. Aside from aesthetics, these things are meaningful to us.”

Some pieces, such as a pair of Italian trompe l’oeil paintings plucked from the estate of designer Bill Blass, harbor memories of friends and colleagues. Kopelman loves trompe l’oeil. “It’s just so interesting and conversationally oriented,” he says. A rack painting by the Anglo-Dutch artist Edwaert Collier (circa 1640-circa 1707) came from Peter Tillou. Schwarz Gallery supplied a John F. Peto (1854-1907) tabletop composition of a tea cup, saucer, rolls and chocolate wafer. “There is a kind of a spiritual quality about looking at these everyday things, yet creating a work of art with that as a subject,” he tells me.

“This is a remembrance of Karl Lagerfeld. It tells you what antiquing is all about,” Kopelman remarks of a French watercolorist’s stool, or tabouret d’aquarelle. He first saw it in an antiques shop in southern France and later, serendipitously, came across it in the Paris residence of Lagerfeld, creative director of Chanel, who later sold it at auction.

Roughly a third of Kopelman’s things came from the Winter Antiques Show or, more broadly, its exhibitors. Joining paintings by Benjamin Champney, A.T. Bricher, Jane Peterson, Fidelia Bridges, Maxfield Parrish, John Marin and Charles Demuth are two strikingly modern florals by Ellen Robbins (1828-1905), one of which belonged to former Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Albert Ten Eyck Gardner. Knowing of Kopelman’s interest, art dealer Thomas Colville called from Maine when he stumbled upon a companion painting by the artist. Kopelman’s favorite picture, the one he would tuck under his arm in a fire, is “May Night” by Oscar Bluemner. He displays it in his den alongside the Adolph Alexander Weinman bronze “Chief Blackbird.”

Kopelman, who professes to be a decorative arts man, shows me a favorite piece of furniture in his cozy den. The English rent table acquired from Thomas Coulborn & Sons offsets a mantel decked with delft pottery supplied by Aronson of Amsterdam. One of his happiest finds was a pair of late Eighteenth Century Dutch tobacco jars made for the American market. A posset pot from the Irwin and Anita Schorsch collection has handles so exaggerated “they look like big ears.”

The Winter Antiques Show chairman worked closely over the years with the fair’s executive director, Catherine Sweeney Singer.

Kopelman chased a bird’s-eye maple New Hampshire secretary for 15 years before the owner of Nantucket Looms reluctantly agreed to sell it. “More than anything, this piece is emblematic of the chase. The hunt is a good part of the fun of it all,” he tells me.

He animatedly describes a recent endeavor, the decoration of the couple’s Indian Wells retreat. “Coco and I had so much fun doing this project. Once we decided on midcentury furniture and with two anchors of folk art, a schoolhouse quilt from Olde Hope Antiques and a hooked rug from Woodard & Greenstein, everything just fell into place,” says the collector, who added a few pieces of African and Native American art, along with a 1930s Indian whirligig from New England, a happy find at Nantucket’s Sylvia Antiques.

Kopelman shrugs modestly when I suggest that his departure will be an incalculable loss for the Winter Antiques Show. “Life goes on. Succession management is key. You need leadership that takes you to the next level. Lucinda and Michael are running the show now. I’m happy to be helpful any way I can, to be a ‘senior advisor,’ as they call the old dudes on Wall Street,” the youthful-looking chairman emeritus, who will be 80 in September, says.

East Side House Settlement is awarding Kopelman its first Heart in Hand Award for public service, to henceforth be presented annually in his honor. The name is in part inspired by the Nineteenth Century motif found among Kopelman’s collection of heart-decorated objects, including a group of heart-in-hand tokens that came from Old Hope Antiques. One of Kopelman’s favorite heart-decorated pieces is a Scandinavian bride’s bowl acquired from London dealer Robert Young. “I love it so much I decided to keep it in New York. It’s a wonderful reminder of all the fun Coco and I’ve had antiquing together over so many years.”

As we say goodbye, the chairman emeritus tells me he is planning to get a father-daughter tattoo. He thought for some time about the design, then remembered the heart motif atop a folk art painted box he bought from John Sideli.

“The hearts are outlined in blue. Two are red, my favorite color. Two are grey, for the Grey Lady, Nantucket. The four hearts are at right angles, much like a four-leaf clover. I’ve been the luckiest guy on the planet,” he says. Several weeks later, the New York Post reported that Arie L. Kopelman, named a Living Landmark by the New York Landmarks Conservancy in 2000, had been spotted at Bang Bang Tattoos getting what those who know him best will recognize as a keepsake of the many years he spent among antiquarians like us.

_fotor.jpg)