“Ezekiel Hersey Derby Farm” by Michele Felice Corné (1752–1845), circa 1800, oil on canvas, 40 by 53 inches. Historic New England, gift of Bertram K. and Nina Fletcher Little.

By Kristin Nord

OLD LYME, CONN. – If landscape is language, then the New England farm has long been its poetic expression. The region’s rugged topography has mirrored how we identify as Yankees; its hills and valleys – and rocky outcroppings – continue to shape our sense of place. Abandoned farmsteads loom as keepers of hidden stories. And in “Art and the New England Farm,” an exhibition curated by Amy Kurtz Lansing and running through September 16 at the Florence Griswold Museum, we see how artists from the Eighteenth through the Twenty-First Centuries have weighed in.

“I sometimes think that one could write the whole human history of my state in terms of the ‘glacier’ alone,” Connecticut’s one-time Lieutenant Governor Odell Shepard wrote. “The stones of the place whetted the wits of Connecticut inventors, turned us from agriculture toward the industrial life, drove our young men forth…with peddler’s packs on their shoulder…and propelled thousands of pioneers from our rock-strewn valleys into the rich and stoneless lands of the Middle West.”

For Puritans, the family farm, nestled near tidy villages, proclaimed self-sufficiency and a non-hierarchical new order. Never mind that colonists were not dealing with untrammeled wilderness. The fertile Connecticut River Valley had been cultivated by Native Americans for thousands of years. But settlers would impose their own ideas upon this landscape. Soon enough, the tidy town and farm as an integral unit would be but one passing expression of an ever-changing way of life. If British and Scottish settlers originally duplicated the land use patterns of their home regions, over time they expanded upon their pastures, meadows and woodlots, and situated their farmhouses farther from town centers.

The Connecticut River Valley boasted both rich glacial till and a distinctive microclimate ideal for the production of shade tobacco and vegetables. Elsewhere, the clearing of land for planting could be a truly arduous process. The stone walls were built out of necessity, the end result of the routine harvesting of “stone potatoes” and carting them to the edges of the property.

As early as around 1800, leaders in agriculture were engaged in research and experimentation, as seen in Michele Felice Corné’s portrait of the 110-acre endeavor on Ezekial Hershey Derby’s farm in Salem, Mass. Similar impulses would lead Connecticut to establish a land-grant college and the Connecticut Agriculture Experiment Station by the late 1800s. At the same time, factories, like the woolen mills and cotton mill in an 1836 woodcut by John Warner Barber, suggest that industrialization was underway.

As early as around 1800, leaders in agriculture were engaged in research and experimentation, as seen in Michele Felice Corné’s portrait of the 110-acre endeavor on Ezekial Hershey Derby’s farm in Salem, Mass. Similar impulses would lead Connecticut to establish a land-grant college and the Connecticut Agriculture Experiment Station by the late 1800s. At the same time, factories, like the woolen mills and cotton mill in an 1836 woodcut by John Warner Barber, suggest that industrialization was underway.

“I like to think of Connecticut not as the Nutmeg State, but as the ‘Provision State,'” Kip Kolesinskas, a conservation scientist, commented recently. “We would not have won the American Revolution without it.” Kolesinskas asserts that the imported traditions of succession had a greater effect on the declining family farm than the challenges of working the land. The completed construction of canals and railroads opened up markets to farmers in the West. This in turn proved fatal to Connecticut’s sheep, apple and salt-hay cultivation. New England farmers, in other words, needed to be nimble. And as Ellsworth Grant asserts in The Miracle of Connecticut, it would appear that settlers were up to the task. “In winter, every farmhouse had to be a domestic workshop, with a spinning wheel and a loom. Grist, saw and fulling mills, as well as blacksmith shops, were common in most villages. Clever artisans turned out tin pots, pans, shoes, hats, buttons and wooden clocks. The state became the leader in the number of patents granted per capita until 1930, he reports.

The farm as pastoral idyll was promulgated in the wildly popular hand-colored prints published by Currier & Ives in the 1860s. These featured sunny scenes by George Henry Durrie of Connecticut farm life insulated from the outside world. For a war-weary country, the appeal of these prints, costing between 50 cents and $3 each, was universal.

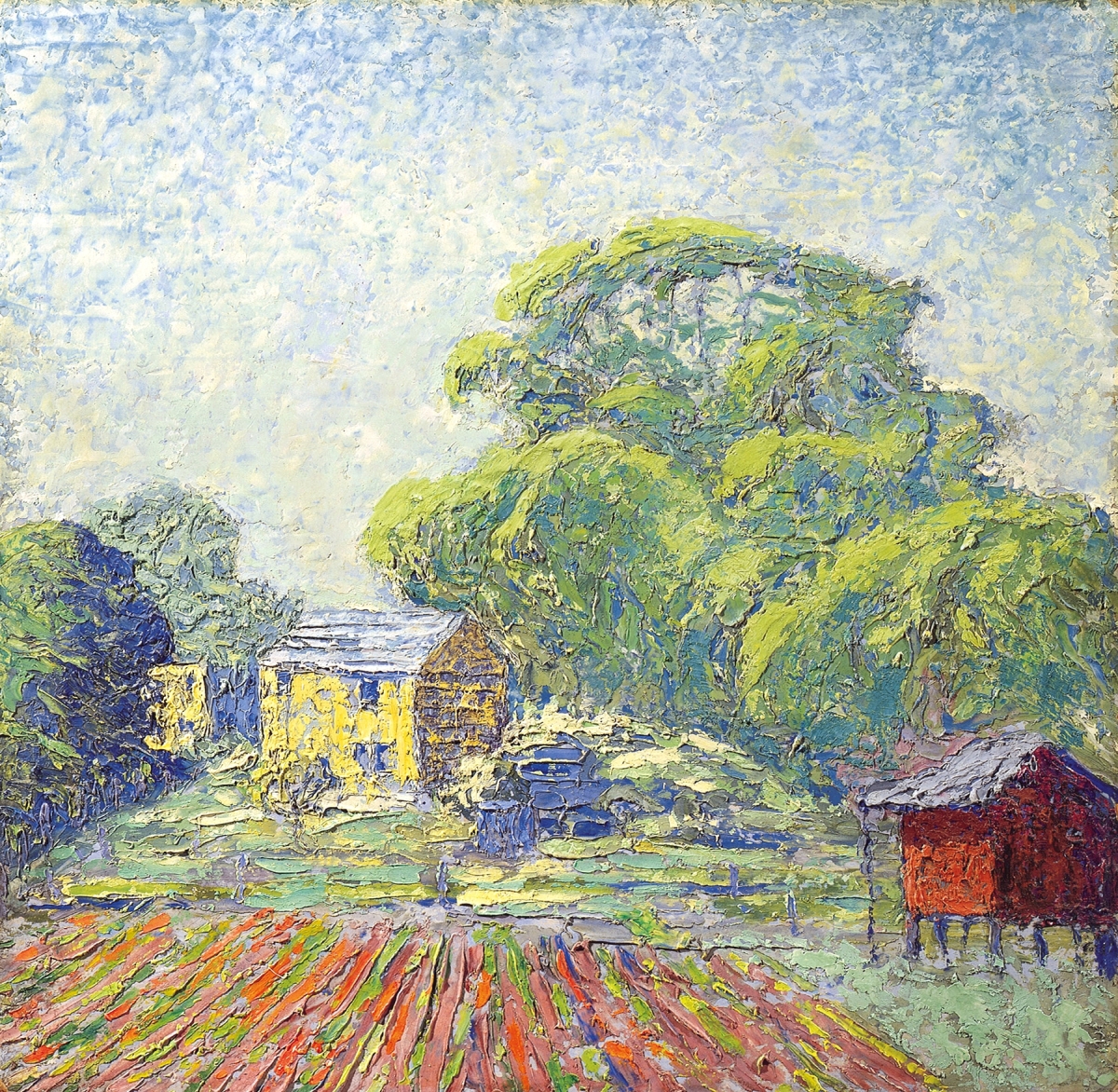

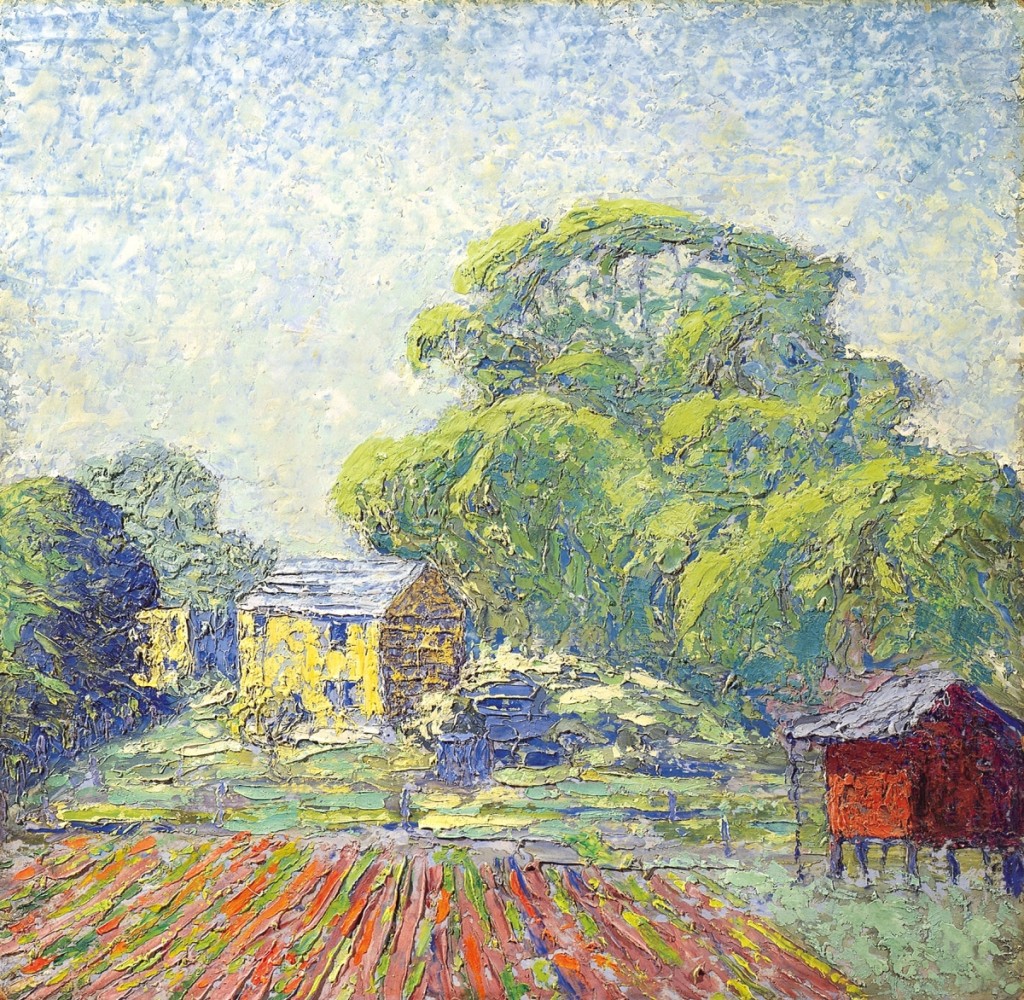

By the start of the Twentieth Century, American Impressionists flocking to the Lyme Art Colony were captivated by the beauty of Florence Griswold’s property, with its bounteous flower and vegetable gardens, its orchards and riverfront pastures. “Depictions of the ideal,” according to J.B. Jackson, author of Discovering the Vernacular Landscape, “were preferred to images of drudgery. Most non-farmers preferred to imagine a simple yet noble calling rather than a struggling economic endeavor.”

“Summer Landscape” by George Henry Durrie (1820–1863), 1862, oil on canvas, 22 by 30 inches. Florence Griswold Museum, gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company.

Both Everett Warner and Breta Longacre captured scenes of converted outbuildings; Carleton Wiggins and Edward C. Volkert were drawn to aspects of the rural farm life that were vanishing. Wiggins saw the allure of his subject matter as part of a homing instinct, for “country-bred people who live in cities, towns or villages but recall their boyhood and the farm surroundings.” Volkert’s emphasis on field hands and a hay wagon and livestock in “Ox with Hay Wagon” resonated with viewers during the 1920s, when physical labor was rapidly being replaced by machines.

Genre paintings romanticized aspects of farm life even as these pursuits were no longer viable. American Impressionist artists Benjamin H. Coe, George Glenn Newell and Mathias Alten painted lyrical compositions that celebrated the hand harvesting of salt hay, a seasonal chore that pressed flat-bottomed scows into service. William Henry Howe, trained in the European tradition of animal portraiture, focused to stunning effect on the manifest otherness of cows.

J. Alden Weir, Childe Hassam and John Henry Twachtman found inspiration on individually owned farm properties which placed them, Twachtman said, “nearer to nature.” And several artists who painted en plein air in Old Lyme set down roots there, creating works that championed verdant fields, vernacular buildings and livestock.

Into this evolving story, the Griswold Farm in Old Lyme followed the regional pattern. The property was purchased in 1841 by the youngest of many Griswold sons in a family that grew up on an ancestral estate nearby. While other siblings went West, lured by the prospects of land, Captain Robert Harper Griswold spent his career as a transatlantic packet-ship captain who transported immigrants and cotton. He bought his property as a wedding gift, intending it to support small-scale farming. At the turn of the century, when the Lyme Art Colony was created, the farm’s natural attributes provided prime subject matter. En plein air artists captured the lushness of the property’s gardens, orchards and meadows, as well as the farm’s converted outbuildings.

“East Hartford Meadows” by Milton Avery (1885–1965), 1922, oil on Upson board, 23 by 23 inches. Florence Griswold Museum, gift of the Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company.

Summers were replete with fresh fruits and vegetables. One cannot help but connect today’s farm-to-table movement with the ecstatic renderings of Miss Griswold’s veranda laden with bounteous tables.

“Art and the New England Farm” ends with a poignant coda. Photographic excerpts and text from the book A Year at Tiffany Farms chronicle a final year of a nearby dairy farm that ceased its dairy operations last year. The Tiffany farm had been in operation since 1841, and Judy Friday, an artist who lives nearby, immersed herself in the farm’s story as it moved from season to season. In 1940, she tells us, Connecticut still boasted 6,233 dairy farms. By last year that number had dwindled to 117. Economic and regulatory uncertainties have made it exceedingly difficult for the small dairy farm to survive. As the viewer takes in the beauty of this farm, one must acknowledge that this way of life is no longer sustainable. We may wish to cling to these places, every bit as evocative as those brought to us in Ox-Cart Man, Donald Hall’s award-winning children’s book, but such farms must make room for a new order.

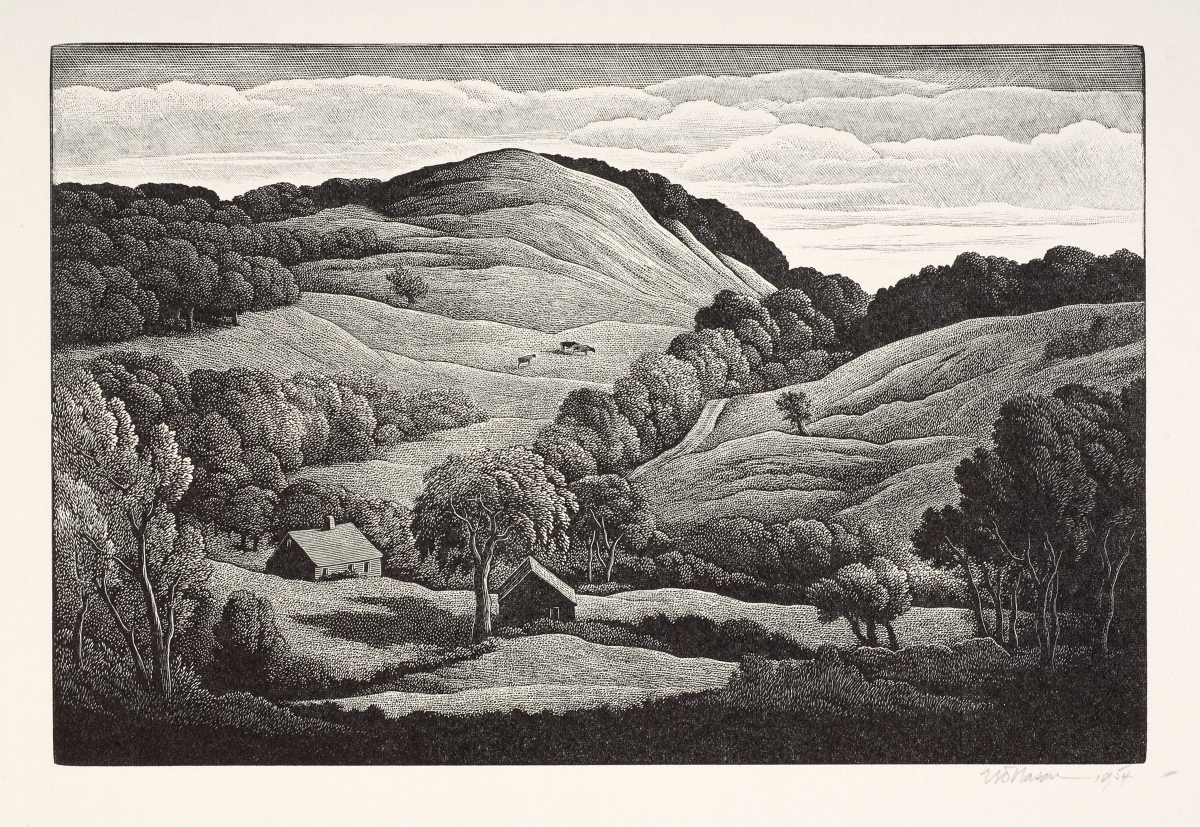

“Perhaps no regional type has attracted to itself more myths and libels than the sensible, self-dependent, God-fearing, freedom-loving, conservative, industrious, stubborn, practical, thrifty, inventive and acquisitive Yankee,” Shepard writes, in Connecticut: Past and Present. The haunting beauty in the remnants of abandoned farmsteads looms and lingers. These elements continue to exert an impact upon our imaginations and remain embedded as fossils a geologist might encounter. For artists Henry Pember Smith, Nelson A. Moore, Chauncey Foster Ryder and Charles Ethan Porter, these remnants underscore the region’s resilience, while for the photographer Walker Evans and artist Thomas Nason we absorb their works as poetic symbols. Milton Avery trumpets the vestigial vitality of farmland in “East Hartford Meadows” with bright color and exuberant brushstrokes.

Today, Connecticut agriculture boasts thriving greenhouse, floriculture, nursery and sod sectors, with annual sales of $252.9 million. Egg, poultry and dairy come next, and shade tobacco, grown under cloth, still produces some of the world’s finest cigar wrappers.

“Americans have come to expect ‘cheap food,'” Kolesinskas notes, observing that moving toward locally grown sustainable agriculture will require education and rethinking. “Someone driving a $50,000 car will give a farmer a hard time about the price of a tomato.” Yankee nimbleness is once again helping Connecticut farmers recast their futures. Long-abandoned land is being farmed again under farmland preservation initiatives. New technologies and value-added products are creating new markets.

“The challenge will be to develop sustainable agricultural models and to protect the ecosystems and mosaic of critical habitat afforded by these lands,” Kolesinskas says.

Florence Griswold Museum is at 96 Lyme Street. For information, www.florencegriswoldmuseum.org or 860-434-5542.

Kristin Nord is a journalist who divides her year between Connecticut and Nova Scotia.