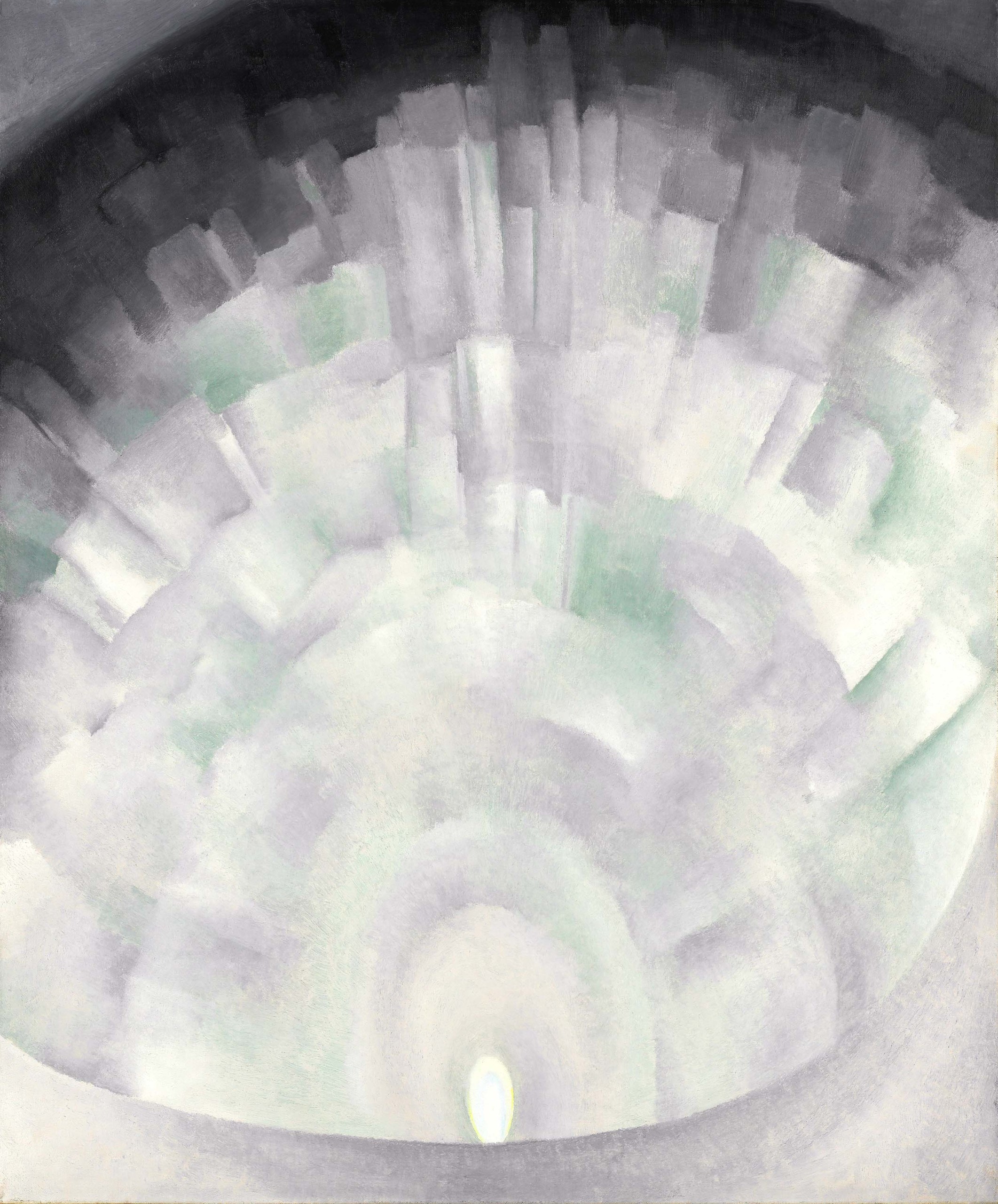

“East River from the Shelton (East River No. 1)” by Georgia O’Keeffe, 1927-28. New Jersey State Museum Collection. Purchased by the Association for the Arts of the New Jersey State Museum with a gift from Mary Lea Johnson. ©Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Peter S. Jacobs photo.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

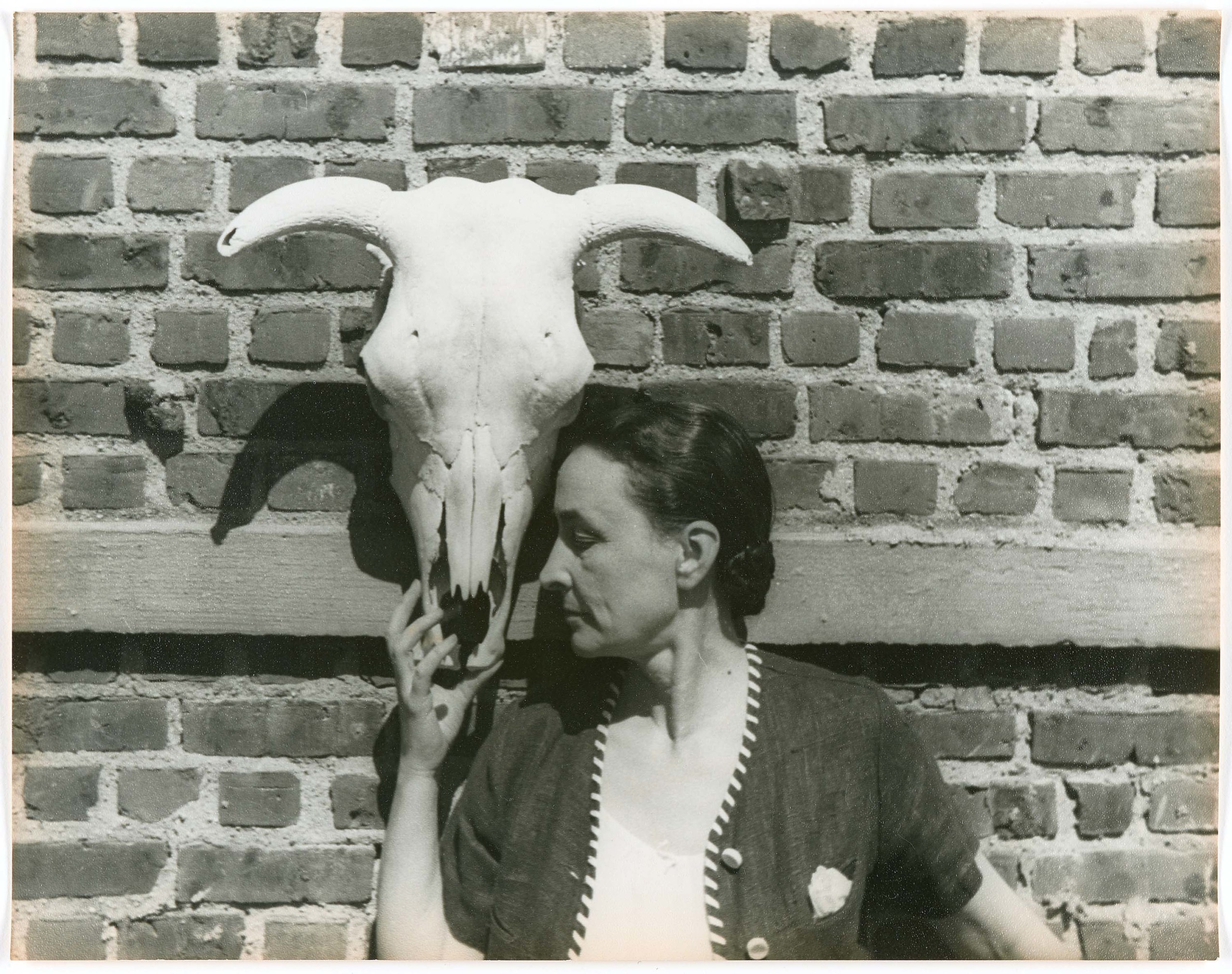

CHICAGO — “My New Yorks would turn the word over,” wrote Georgia O’Keeffe to critic Henry McBride in 1925. The words came out of frustration, since her agent/dealer/husband, the photographer Alfred Stieglitz, had just elected to exclude a New York architectural view from a group exhibition at Anderson Galleries. But O’Keeffe persisted in creating them, and Stieglitz came around — and today O’Keeffe’s New Yorks are among her most recognized and celebrated works. “Georgia O’Keeffe: “My New Yorks” is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) through September 22.

Taken in its original context, O’Keeffe’s phrase “my New Yorks” referred to her physical paintings of New York, but the curators of the exhibition — Sarah Kelly Oehler and Annelise K. Madsen, both of the AIC — have also interpreted it more broadly. “‘My New Yorks’ is her translation of her experiences of the world around her, of her area of Midtown Manhattan that is where she is experiencing this dynamic city on the rise,” Madsen explained. Manhattan was, indeed, O’Keeffe’s primary home for 40 years, between 1918 and 1949, and the city is threaded throughout the work she produced during that time.

Its presence is most keenly felt in her paintings of the New York skyscrapers, dazzling views from below and above where the sharp angles of this entirely new kind of building extend into and create shapes in the sky. In many paintings — including “New York Street with Moon” (1925), the earliest skyscraper painting in the show — artificial and natural light sources create dazzling optical effects. The defining example of this is the AIC’s own “The Shelton with Sunspots” (1926), where the monumental building in the center of the canvas is refracted by the morning sun tucked just behind it — O’Keeffe later remembered it as “the optical illusion of a bite out of one side of the tower made by the sun” — creating a shower of sequin-like sparks.

“The Shelton with Sunspots, N.Y.” by Georgia O’Keeffe, 1926. The Art Institute of Chicago, gift of Leigh B. Block. ©Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York City.

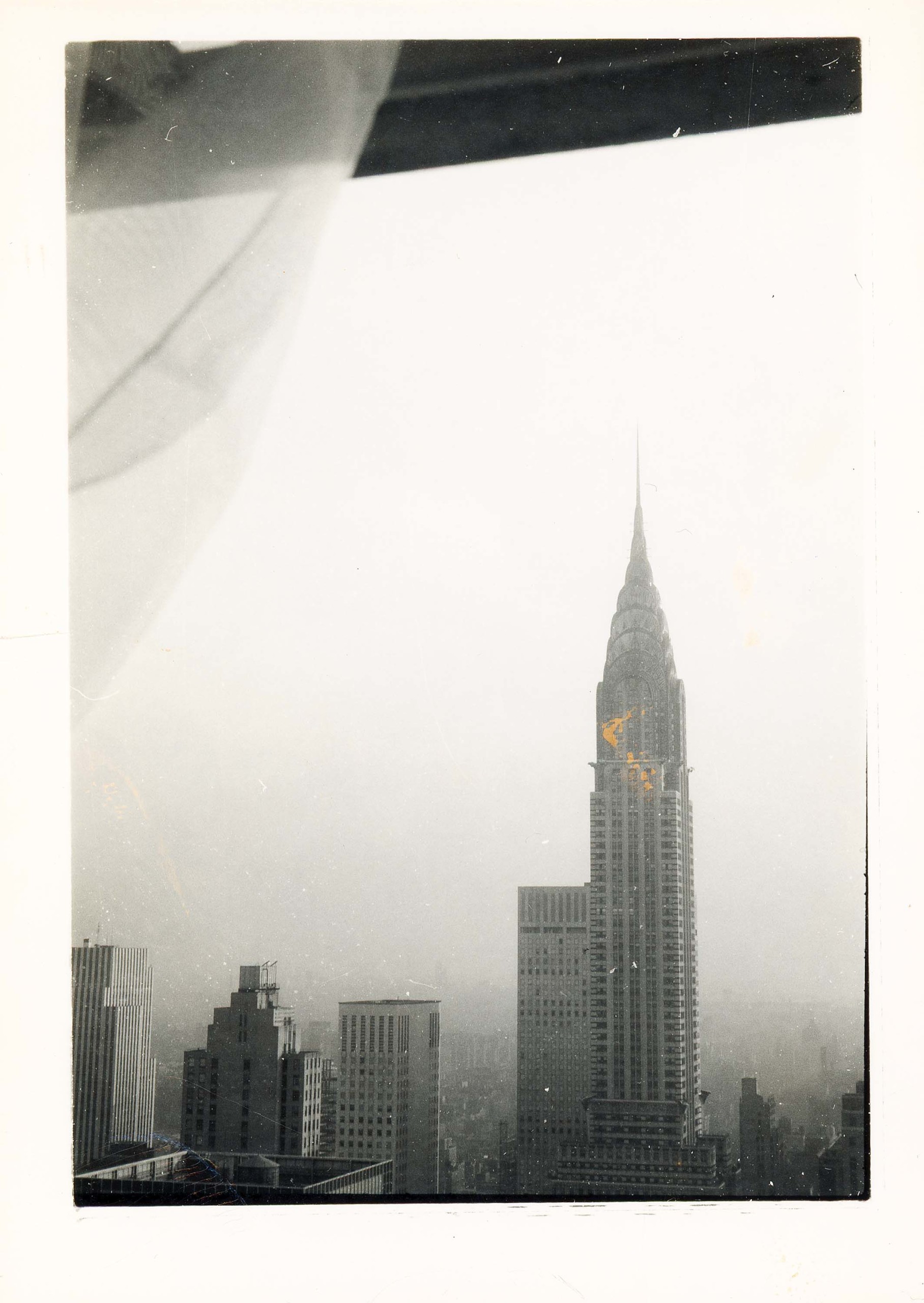

The Shelton was more than just an attractive subject; it was also O’Keeffe and Stieglitz’s shared home for more than a decade. The 31-story building, purportedly the tallest skyscraper in the world when it was built in 1923, was the first of its kind: a high-rise, residential hotel in the bustling center of New York. O’Keeffe and Stieglitz moved there permanently in 1925 and eventually ended up on the highest residential floor, which delighted them. Stieglitz said that being up so high was like being “out at mid-ocean — All is so quiet except the wind.” The Shelton was equally glad to have them; a 1926 issue of the Shelton Spotlight, the building’s weekly newsletter, features a cover story on neighbor “Miss O’Keeffe,” “considered the foremost woman painter of America.”

One of the discoveries of this exhibition is that Stieglitz and O’Keeffe had, in fact, lived at the Shelton briefly in 1924, the year before they moved there on a more permanent basis. This “doesn’t sound earth-shattering,” said Oehler, “except that it actually then offers a better explanation of why she began painting and creating all these works. Ultimately it was this sort of tremendously radical new experience for her, living up on high, that drove so much of her curiosity.” Oehler also points out that her reference to “my New Yorks,” plural, in that letter to McBride makes more sense when we realize she had probably been benefiting from that view for some time already, and that the phrase refers to more than just the one painting Stieglitz excluded from the 1925 show. There are, in fact, skyscraper paintings we will never know about, since O’Keeffe often destroyed paintings that she found “unsuitable”; one of those is a view of the Shelton at night now known only as black and white reproduction from a 1927 magazine.

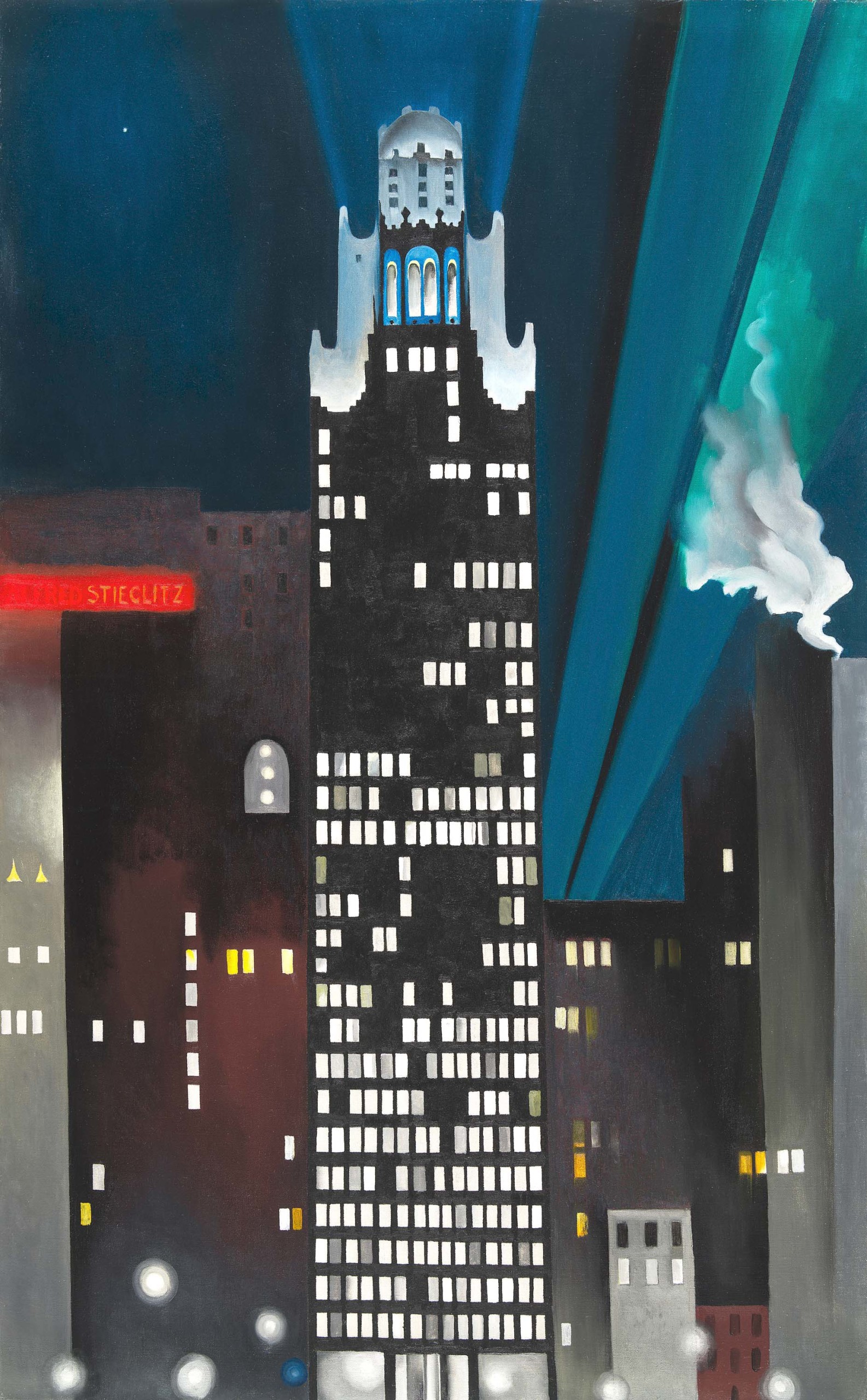

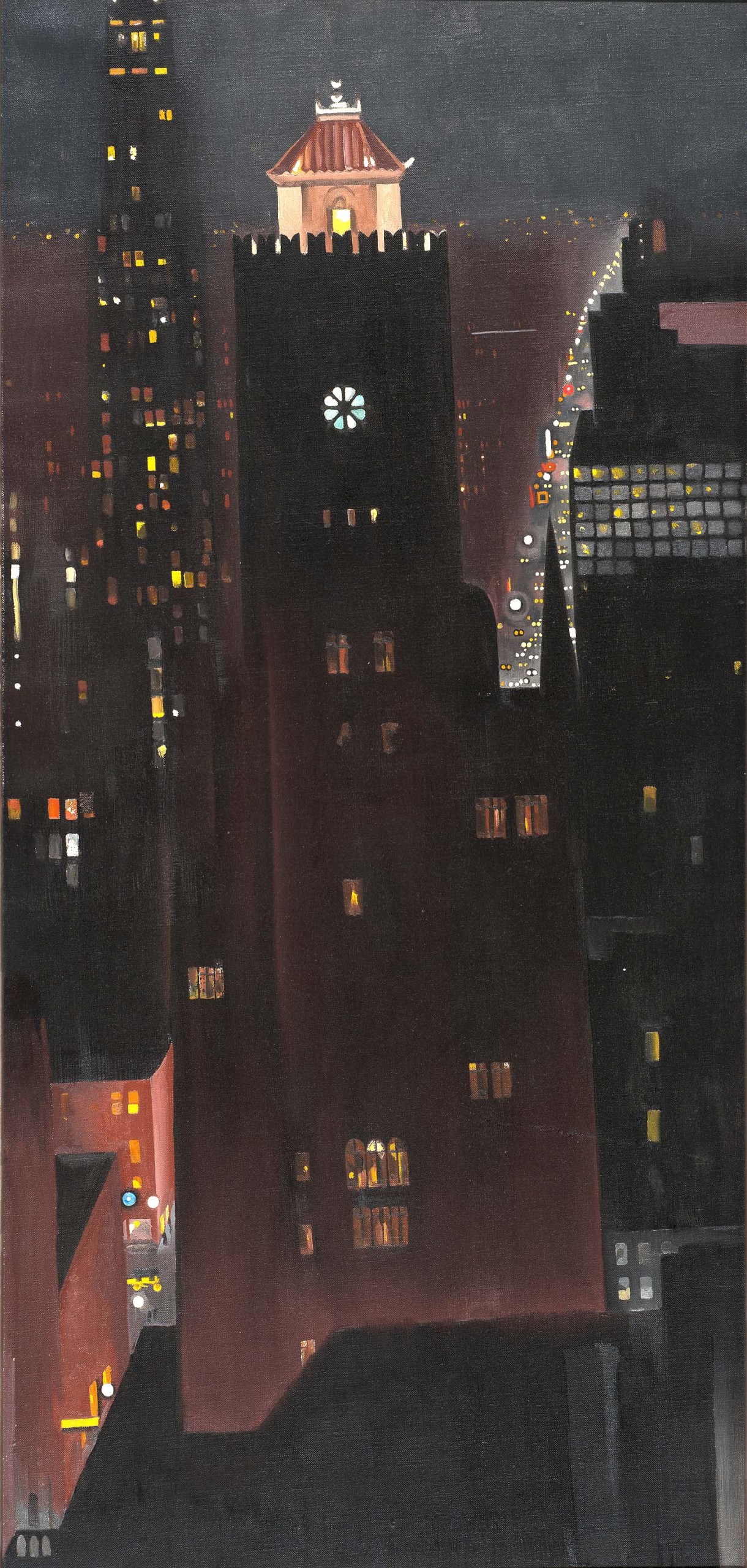

“New York, Night” by Georgia O’Keeffe, 1928-29. Sheldon Museum of Art, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Nebraska Art Association Thomas C. Woods Memorial. ©Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Bill Ganzel photo.

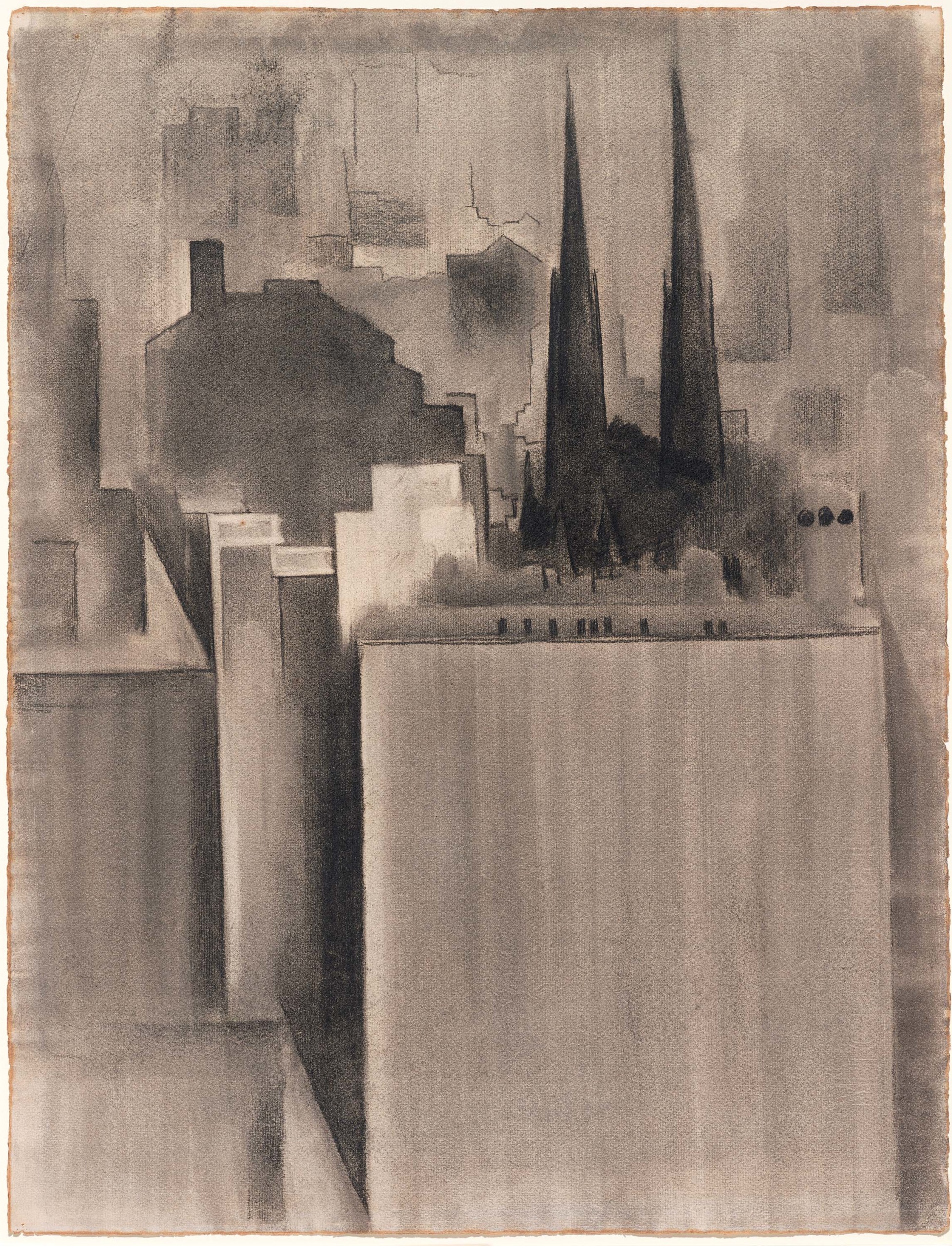

“New York, Night” (1928-29), done from within the Shelton, looks down at the dark city ablaze with electric lights. In her catalog essay, Oehler wrote about the “canyonlike experience of the streets far below — the dark crevices formed by tall buildings,” a view only possible from that elevated, privileged view. Oehler and Madsen agree that there is something powerful in O’Keeffe suddenly gaining this perspective of a city she had already experienced so thoroughly from the ground. Even before she moved to the Shelton, Oehler said, “she’s already thinking in terms of an apparent abstraction, geometries of shifting angles that would change as she moved about the city.” From up high, “she’s interested in this very sharp view looking downward and often abstracts it completely,” something you can see her working out in studies like Untitled (“New York”) (1925-26).

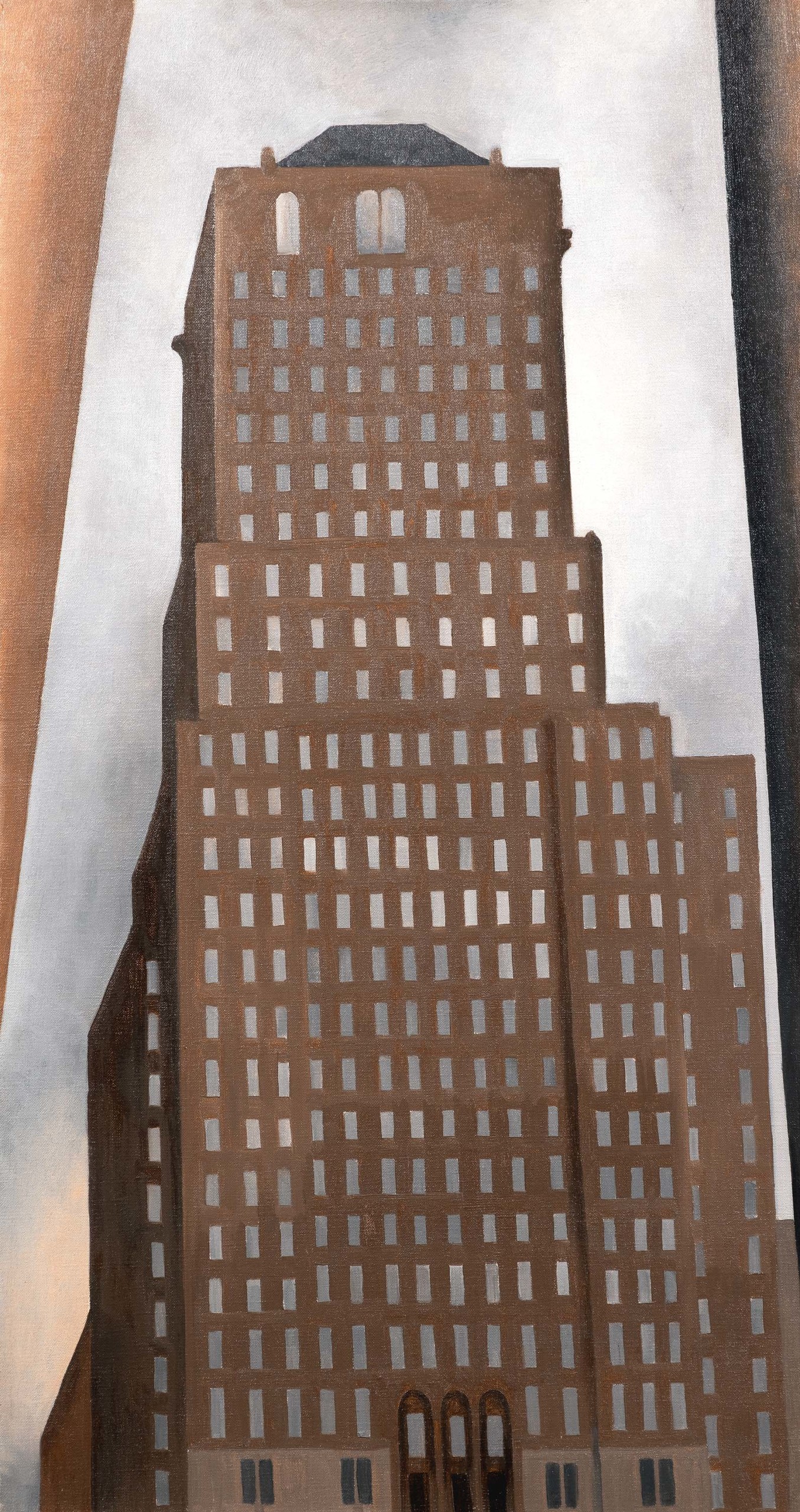

The stable vantage point of the Shelton also offered O’Keeffe the opportunity to work in series, notably the many views from her east-facing windows that overlooked the river. “She is painting the view from the window that she sees every day,” Oehler said, “whether it’s sunny, whether it’s cloudy, whether it’s snowy — and it’s about that experience sort of writ large and manifested through her visual perception of the world.” Works like “East River from the Shelton” (1927-28), “East River from the 30th Story of the Shelton Hotel” (1928) and “Pink Dish and Green Leaves” (1928-29), which shows the busy riverscape just beyond a windowsill still life, demonstrate not so much an evolution over time but a snapshot of how the prospect changed for her on a daily basis. Madsen adds that working in series like this was an essential aspect of her approach. “She’s not doing it in multiple takes to try to get it right; she’s doing it…to see where a kind of approach to abstraction and shape and color can take her.” It’s worth noting that Stieglitz loved the changing view, as well; several of his photographs from their apartment are included in the show.

“Pink Dish and Green Leaves” by Georgia O’Keeffe, 1928-29. Private collection. ©Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. Bruce M. White photo.

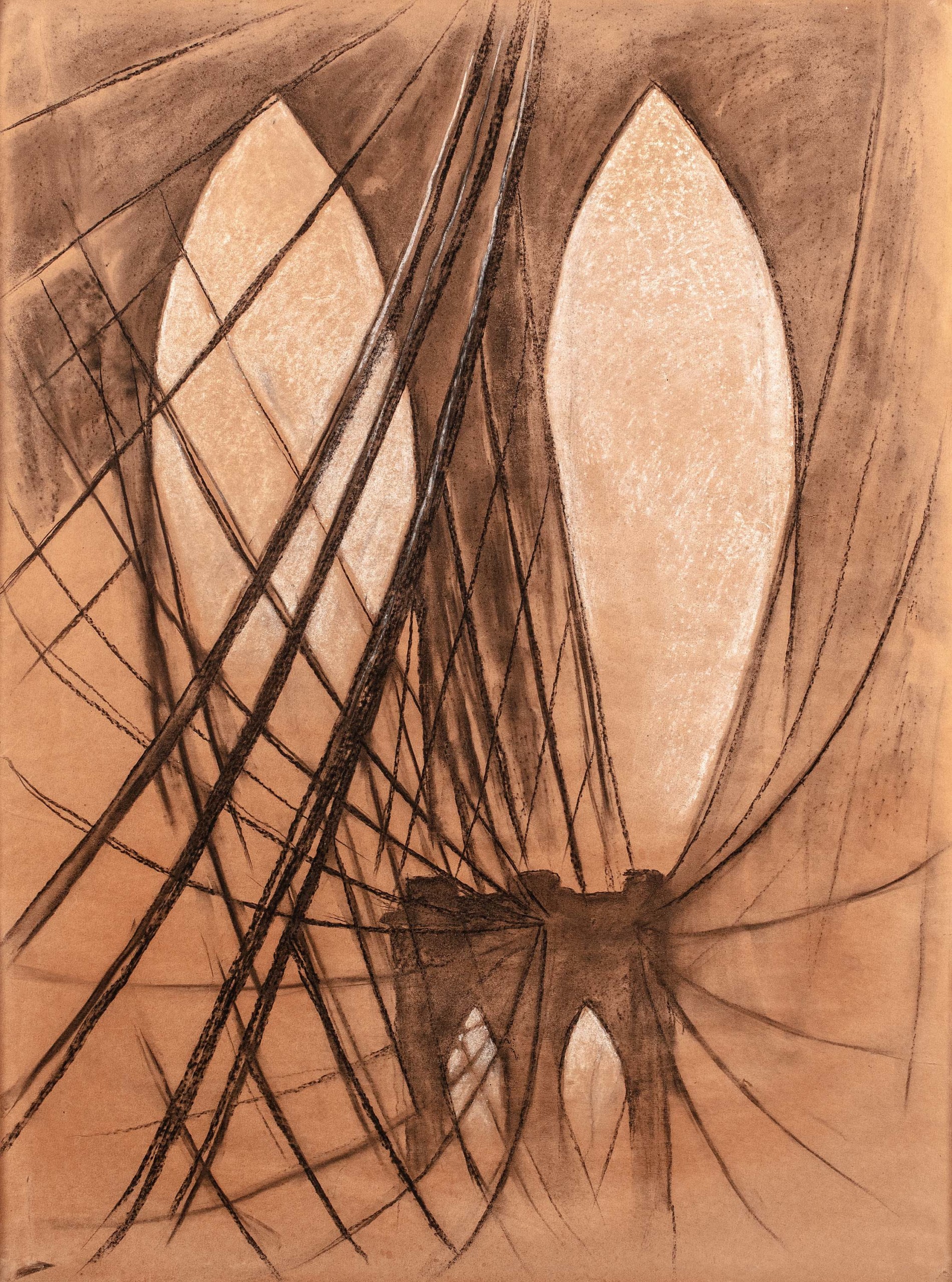

But she remained a walker, continuing to produce dramatic sidewalk-level views of New York’s architecture inspired by her rambles at all times of day. “Shelton Hotel, N.Y., No. 1” (1926), for instance, shows the distinctive profile of her apartment building from below, midday, seen from within one of those “canyons.” O’Keeffe’s perambulations also gave her the opportunity to see the famed Radiator Building on West 40th Street as it was being constructed. The building’s eclectic combination of Neo-Gothic and Art Deco influences, along with its glossy black cladding and gold details, made it something of a sensation when it went up in 1924. O’Keeffe later recalled, “I walked across 42nd Street many times at night when the black Radiator Building was new — so that had to be painted, too” — in a dramatic nighttime view that also bears a neon sign flashing Stieglitz’s name (“Radiator Building – Night, New York,” 1927).

O’Keeffe’s frequent use of black — both as an indication of a thing, like the surface of the Radiator Building, or a non-thing, like the night sky — summons up the question of absences in her work. A catalog essay by Adrienne Brown touches on the kind of Blackness we don’t see in O’Keeffe’s oeuvre by paralleling her New York works with those of Harlem Renaissance artist Aaron Douglas, who also painted nighttime views. O’Keeffe’s decision to, unlike Douglas, eliminate from her city views the people who moved inside, outside, and among those architectural spaces presents a racially (and economically) neutral view of the rapidly growing and diversifying city. Essayist Sascha Scott also notes the story of Indigenous labor that is behind New York’s famous skyline and is absent from O’Keeffe’s works. Oehler explains why she and Madsen sought out these perspectives: “We both felt it was really important that O’Keeffe not be seen in complete isolation from what’s happening all around her.”

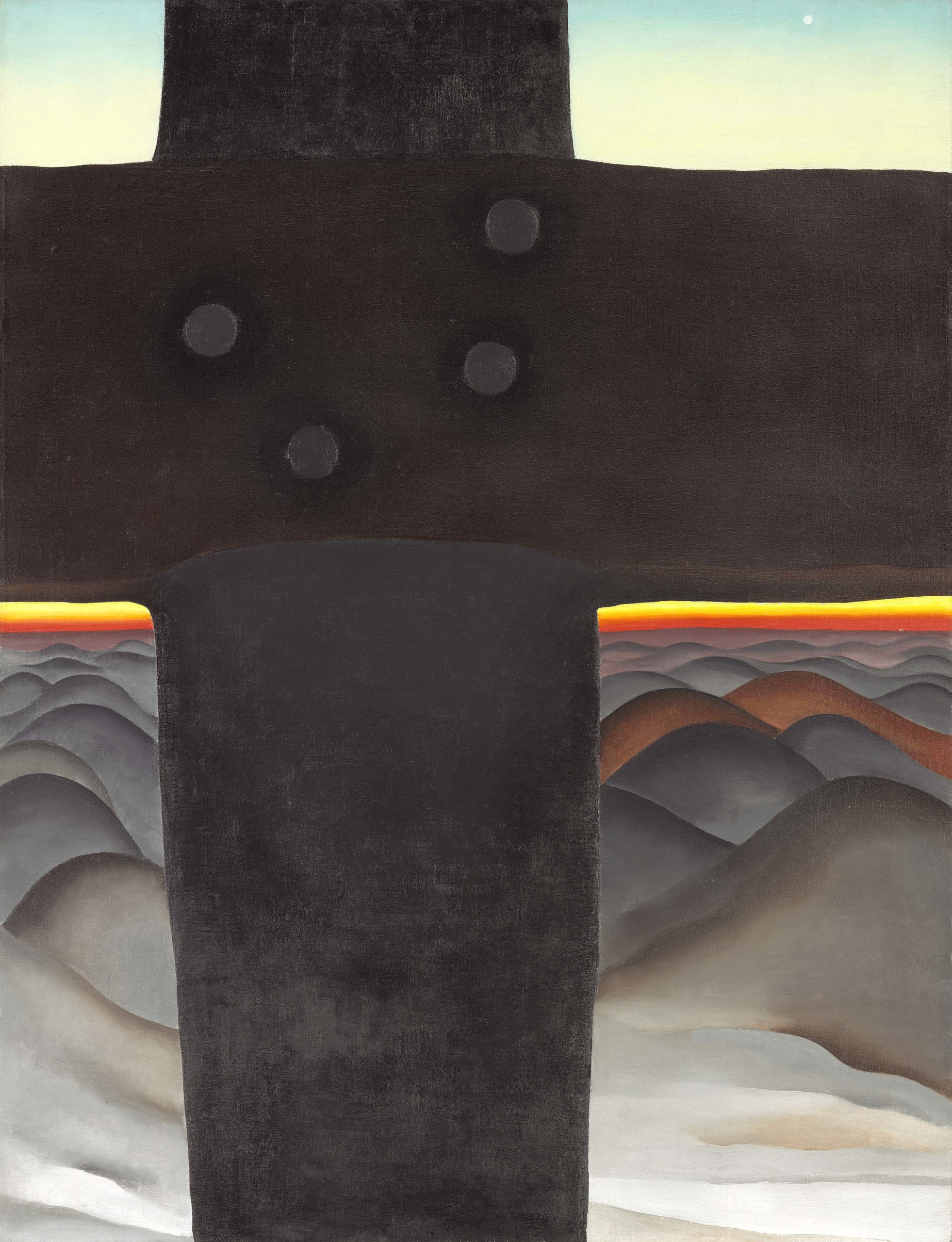

“Black Cross, New Mexico” by Georgia O’Keeffe, 1929. The Art Institute of Chicago, Art Institute Purchase Fund. ©The Art Institute of Chicago.

Black appears in nonhuman but hardly neutral guises in O’Keeffe’s work. Oehler writes about how the public reception of the Radiator Building was surprisingly racial at the time (one critic wrote, “Here is a barbaric note. You think of tom-toms and gleaming spearpoints”) and says it is not unreasonable to think O’Keeffe would have been aware of such analyses. Her “Black Cross, New Mexico” (1929) is rife with ambiguous symbolism, a fuller and most ambitious expression, perhaps, of the deep tones and network of dark veins in her “Pattern of Leaves” from 1923. But also, Oehler said, “There is just the formal intrigue of it” — the challenge of painting black on black and figuring out how to differentiate tones, the visual excitement of natural and artificial light against a black building and a black sky. “She’s fundamentally thinking through color, and black is just a really strong counter-position to any color that you put into a composition.”

Madsen noted that O’Keeffe also does something similar in white, notably in one of the most intriguing works in the show: “New York – Night (Madison Avenue)” (1926). Rendered in abstract, angled lines and planes of gray, white and yellow, the painting does not noticeably represent either night or Madison Avenue. Here, Oehler wrote, “She rendered the experience [of street-level New York] in completely non-objective terms, reveling in seeing the city’s intersecting lines as pure form.” This work acts as something of a hinge connecting paintings that are recognizably of New York to other works in the show, which include abstractions, still lifes and New Mexico scenes. Madsen explained that they were already considering formal resonances with non-New York scenes, but that things “clicked together” when they started looking at exhibition records and photographs from O’Keeffe’s time in the city. “From the start and consistently, O’Keeffe is showing this great variety of works together,” Madsen explained, “so when we started to think about how O’Keeffe was making decisions about what she was showing, then it really made sense to bring those varied works together.” Oehler added, “I think there was an adventurousness there that she wanted to express, but it was also very much about how she saw all these works as a unified project.”

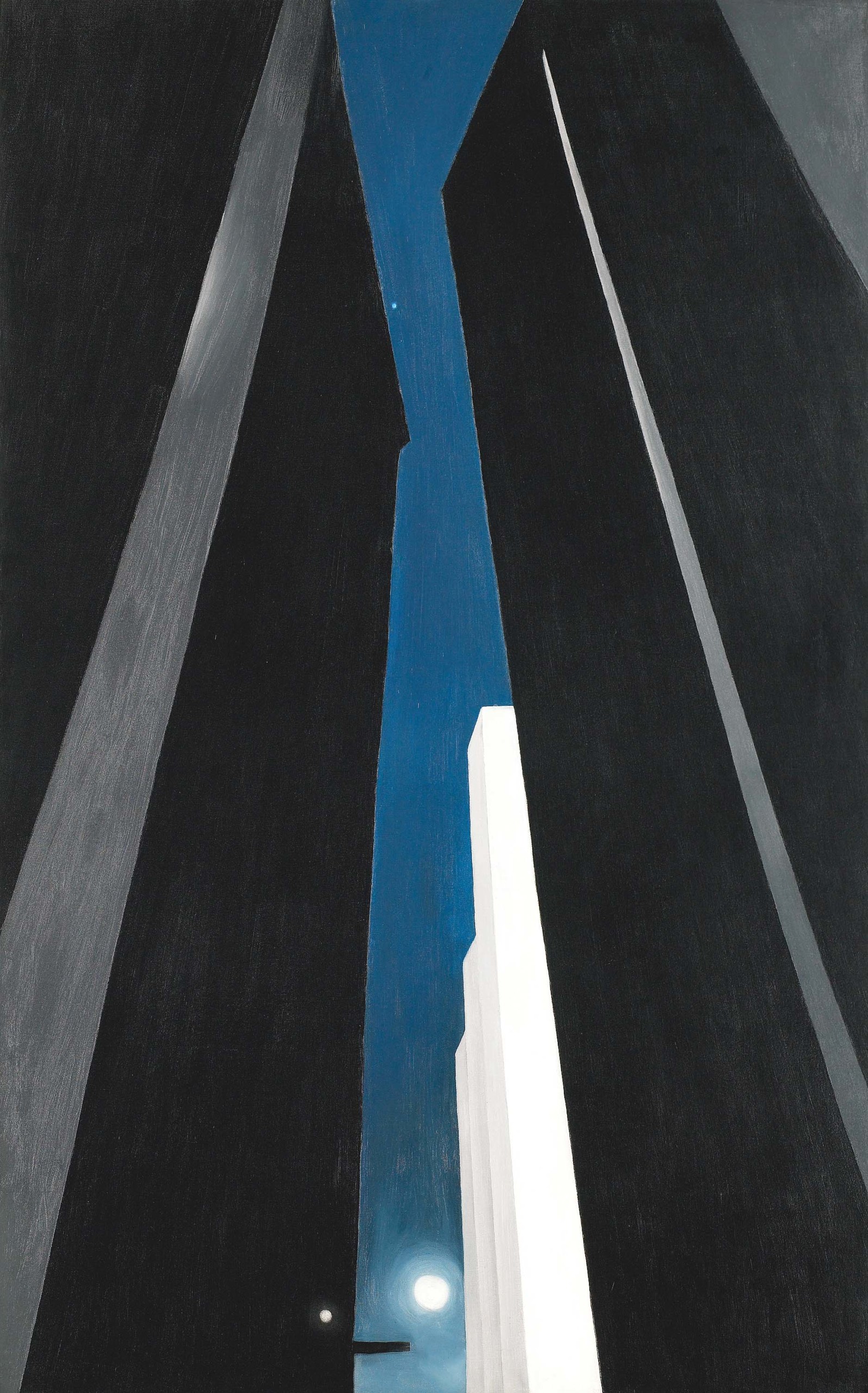

“City Night” by Georgia O’Keeffe, 1926. The Minneapolis Institute of Art, gift of funds from the Regis Corporation, Mr and Mrs W. John Driscoll, the Beim Foundation, the Larsen Fund, and by public subscription. ©Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

Works like “Manhattan” (1932), which shows abstracted city buildings jangled together with calico roses from New Mexico in the place of sunspots, demonstrate the extent to which this is true. And a remarkable pair of paintings, separated by 50 years, will disabuse any notion that she forgot about New York’s canyons in favor of New Mexico’s after she moved there permanently in 1949. “City Night,” painted in 1926, is one of her more stark and abstract street-level views: black, gray and gleaming white buildings, all windowless, surging upward into a deep blue sky, with the moon unexpectedly shining out from the bottom of the canvas. She revisited the composition later in the 1970s, when she was in her eighties, and the result is nearly identical save for the addition of some gleaming stars.

“I don’t think it’s coincidental that it’s coming at the time when she’s also writing her autobiography,” says Oehler. “I think she’s looking retrospectively at her entire career, and this is a moment where she then decides, on a monumental scale, to revisit the subject.” The two paintings are intentionally not next to each other at the AIC; instead the later work is used as “almost a coda,” says Oehler. This jibes with O’Keeffe’s own words on the subject, from that 1976 autobiography: “There were many other things that I meant to paint. I still see them when I am in the Big City.” We are now separated by another 50 years from the later version of “City Night,” and from that lofty vantage point it is appealing to think in these endless terms about the aesthetic appeal of the city, for O’Keeffe and ourselves, both inside and outside the museum.

The Art Institute of Chicago is at 111 South Michigan Avenue. For information, www.artic.edu or 312-443-3600.