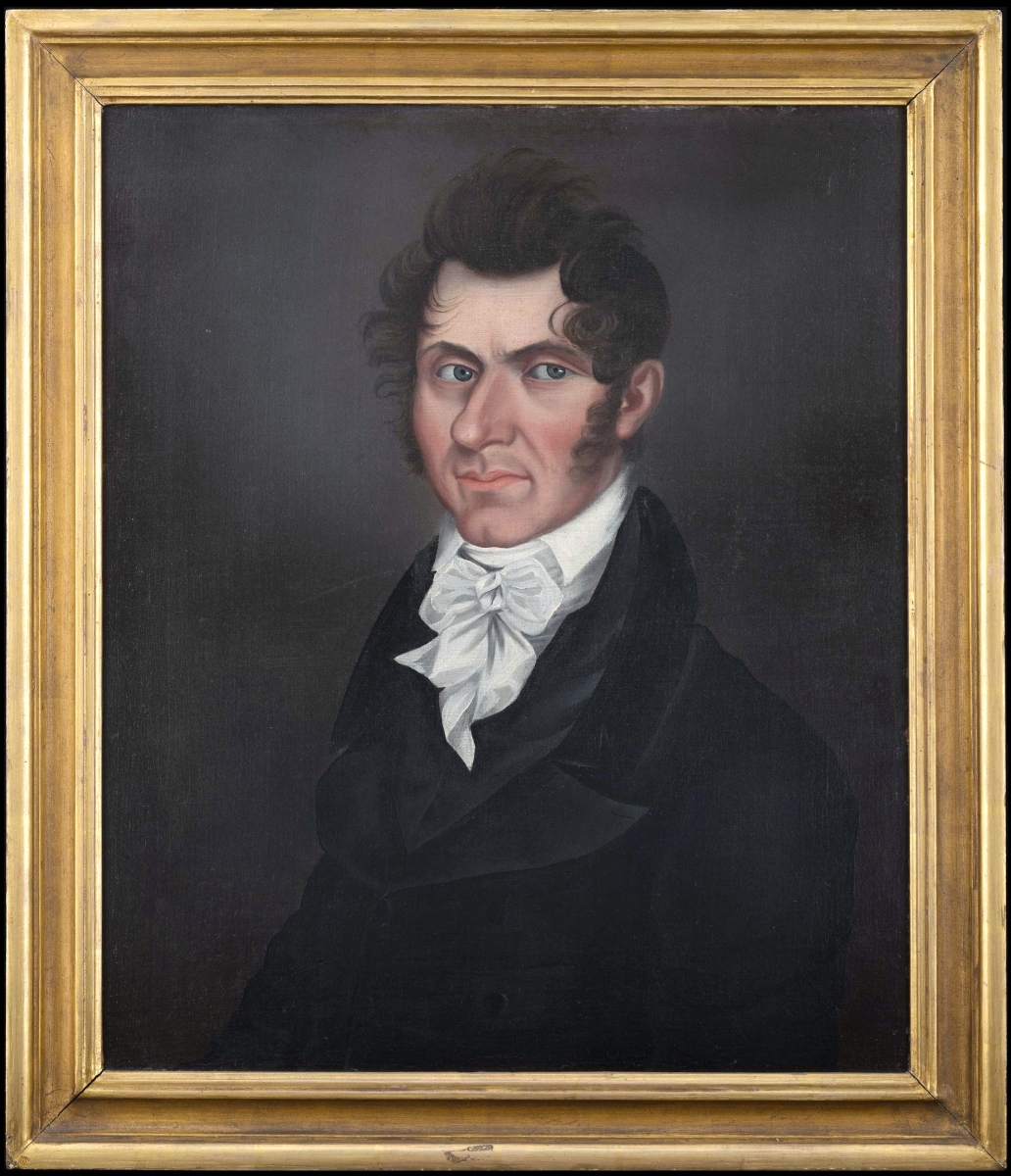

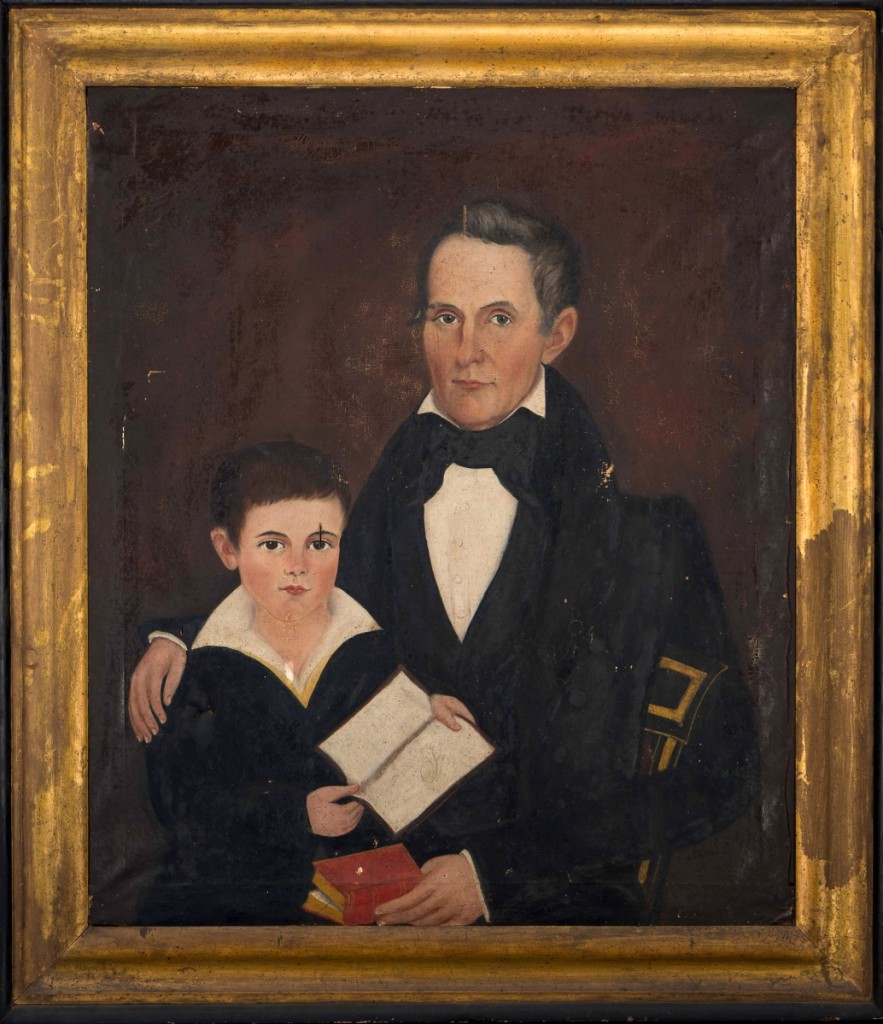

“Portrait of Charles Henry Robertson,” unidentified artist, Charlotte County, Va., probably 1825–30. Oil on tulip poplar panel. Gift of the Boswell family in memory of the subject’s great-great-grandson, John Iverson Boswell, 2012.

By Karla Klein Albertson

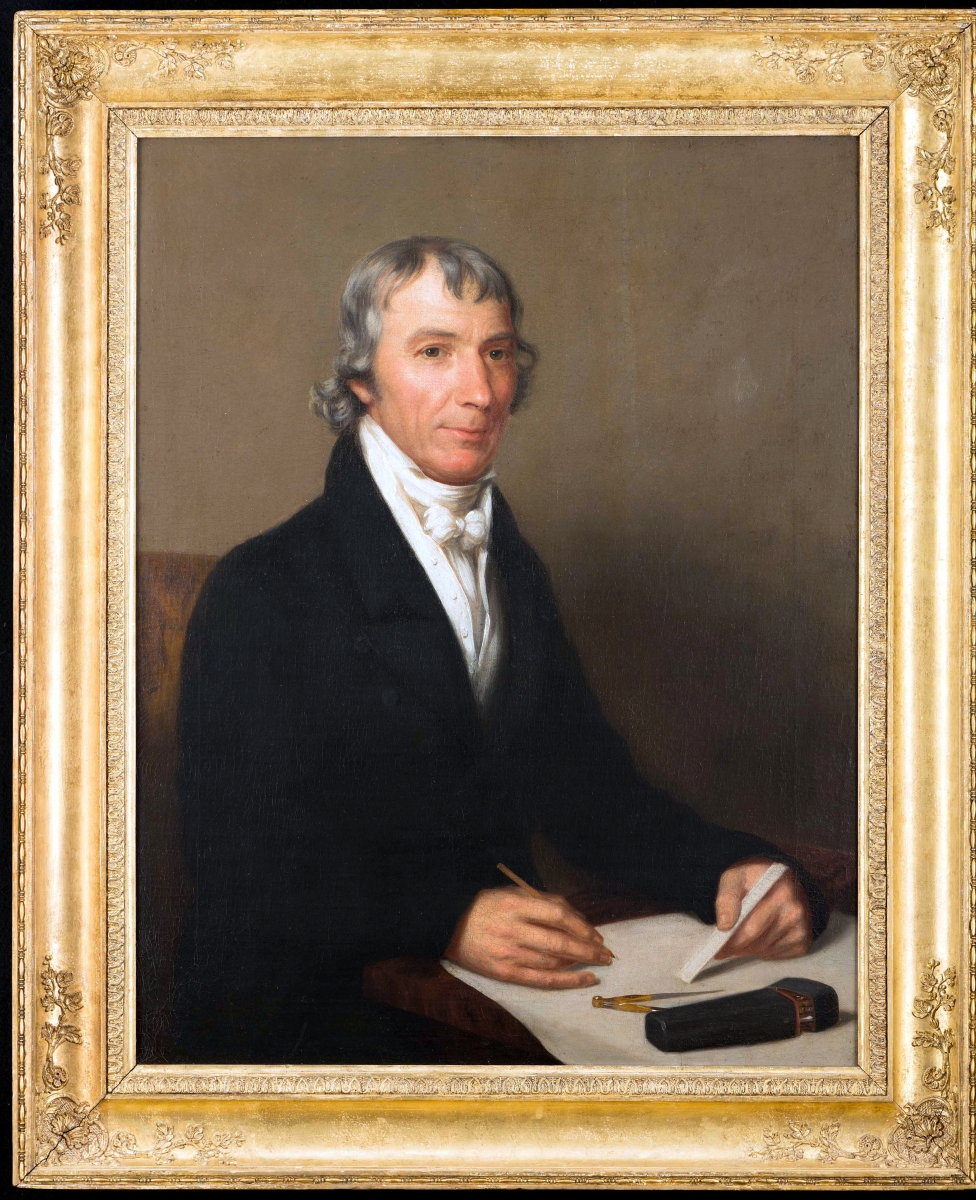

WILLIAMSBURG, VA. – Before wedding albums, baby photos and selfies, Americans captured their appearance at a moment in time through the medium of portraiture. “Artists on the Move: Portraits for a New Nation,” a new long-term exhibition opening November 18 at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum in Colonial Williamsburg, brings together more than 30 portraits of distinctive personalities recorded on canvas by academically trained and self-taught artists. While some likenesses, such as that of Thomas Jefferson and Commodore Perry, are familiar faces, others may be the only surviving record of an unidentified person whose history is worthy of more research.

The paintings exhibited, many for the first time, reveal how people chose to present themselves in the early decades of the Nineteenth Century. The serene smile or dignified gaze, hands holding a favorite book or beloved child – all human expressions that reach across two centuries to link living visitors with ancestors from another age. As the saying goes, every picture tells a story. In the case of portraiture, it is always a twin tale of painter and sitter, and of what decisions brought them together to create the work of art.

Laura Pass Barry, Colonial Williamsburg’s Juli Grainger curator of paintings, drawings and sculpture, was the organizing force behind the exhibition. As she explains, “The goal is to showcase the rich visual breadth of work that was created by many different artists’ hands. I want people to look at these paintings and get an insight on why they were created, the motivation not just of the artist but of the subject. How did they wish to be remembered? As you dig deeper, you start to build relationships, and, for me, creating those relationships between paintings and the artist and subjects is exciting. I want to convey that to the visitors.”

She continued, “The exhibition is really about artists on the move. After the Revolution, people were moving around with much greater frequency than we tend to remember or acknowledge. Many were migrating west and south. Portraiture was a form of art that was generally restricted to the upper classes in the Eighteenth Century. Then, suddenly, more and more people wanted to have their pictures done. Academically trained artists as well as folk portraitists were traveling where the people were going. And there were more painters coming in from Europe. Artists would make Southern trips to Charleston and New Orleans or over to Kentucky, travel down the rivers to the inland parts of the country. In some cases, they would be gone a year or two, in others they would permanently relocate to a new area.”

She continued, “The exhibition is really about artists on the move. After the Revolution, people were moving around with much greater frequency than we tend to remember or acknowledge. Many were migrating west and south. Portraiture was a form of art that was generally restricted to the upper classes in the Eighteenth Century. Then, suddenly, more and more people wanted to have their pictures done. Academically trained artists as well as folk portraitists were traveling where the people were going. And there were more painters coming in from Europe. Artists would make Southern trips to Charleston and New Orleans or over to Kentucky, travel down the rivers to the inland parts of the country. In some cases, they would be gone a year or two, in others they would permanently relocate to a new area.”

To illustrate the exhibition’s theme of artistic movement, the museum sought to fill gaps in the permanent collections by acquiring portraits from a broader geographical area. Colonial Williamsburg’s focus in the past had been on the East Coast, with a strong Virginia collection and memorable folk portraits from New England. To these works curators wanted to add portraits from the backcountry and inland South, from states such as Kentucky and Tennessee. Barry estimates that a third of the paintings in the show were acquired in the last five years, as staff identified examples on its wish list.

In 2016, Colonial Williamsburg acquired the portraits of General Peter Buell Porter and his wife, Letitia Breckinridge Porter. Barry explained, “For six or seven years, we’ve been looking for paintings by Matthew Harris Jouett [1788-1827], an artist who trained with Gilbert Stuart in Boston and went back to his native Kentucky. He is extremely well-known in that region.”

Laura Pass Barry, left, Colonial Williamsburg’s Juli Grainger curator of paintings, drawings and sculpture, and Shelley Svoboda, senior conservator of paintings, examine the circa 1800 portrait of Matilda Morrow by Charles Peale Polk. —Jason Copes photo

General Porter was a veteran of the War of 1812 and served as the nation’s secretary of state. Although the Porters lived in New York State, Letitia Breckinridge came from an important Kentucky political family. The Williamsburg portraits were painted when the couple visited Kentucky in 1819. The Porters join distinguished company, for Jouett is best known for his paintings of Thomas Jefferson, George Rogers Clark and the Marquis de Lafayette.

An even more recent find, made earlier this year, was the addition to the collection of a pair of portraits depicting the Claibornes of Nashville, Tenn., by Ralph E.W. Earl (circa 1788-1838). Earl first trained under his artist father Ralph Earl (1751-1801), but the son’s early naïve portrait style changed into a more polished academic mode after an 1809 visit to London, where he studied with John Trumbull and encountered Benjamin West.

When he was planning a painting of the Battle of New Orleans, Earl visited Andrew Jackson in Tennessee in 1817. There he painted portraits of Jackson and his family, and undertook commissioned portraits of Thomas and Sarah Claiborne, among others. He later accompanied the newly elected president to Washington in 1829, serving as sort of a court painter to the administration. After two terms, Earl returned with Jackson to the Hermitage, the general’s home in Tennessee, where he spent the rest of his life.

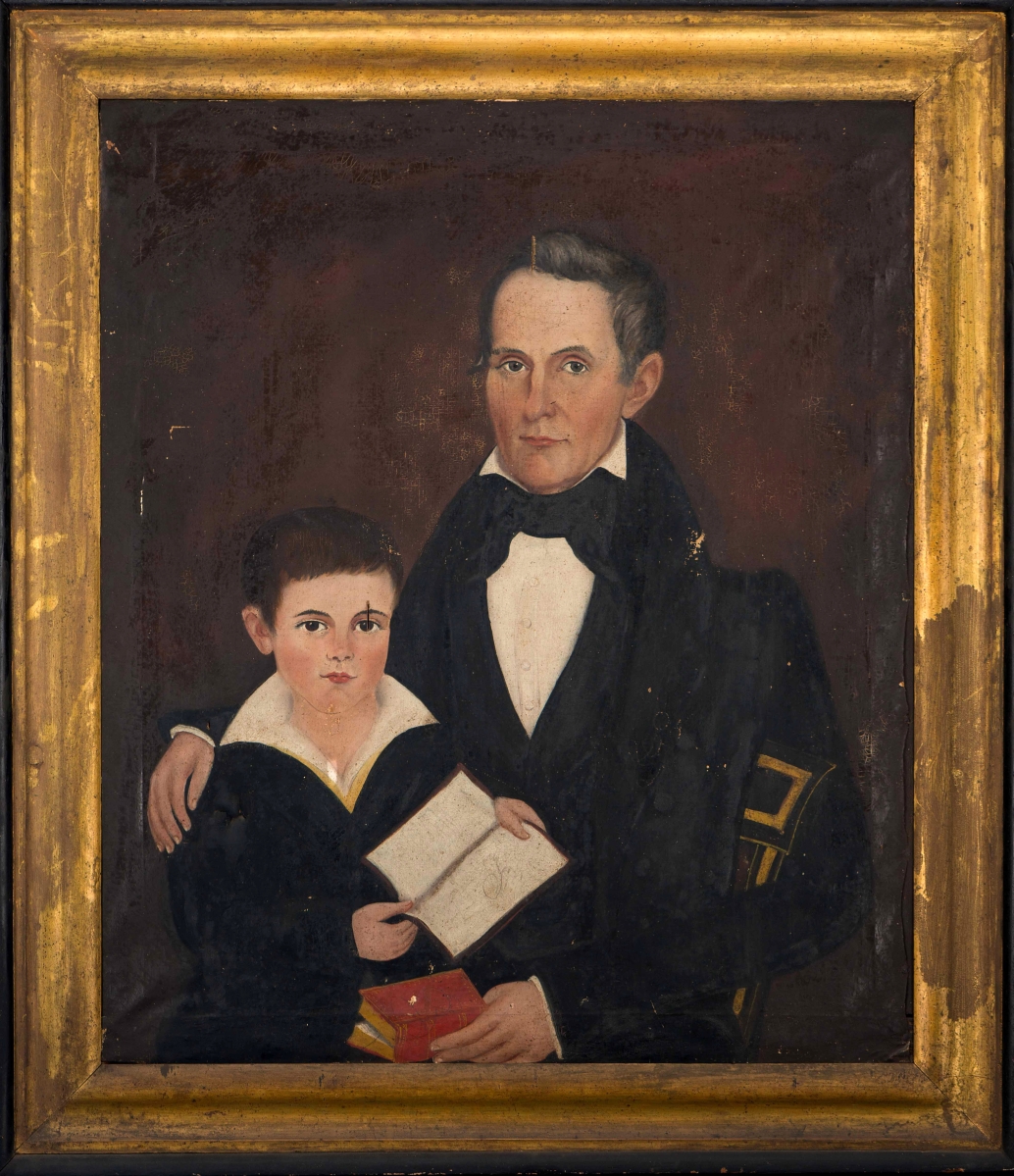

The most charming portraits in the exhibition are the dual images of parents and children. Another 2017 acquisition on view is the portrait of Catherine Macomb Mason and her son John Henry Mason, painted in Philadelphia in 1829 by renowned artist Thomas Sully (1783-1872). Barry was especially pleased to add this nonpolitical subject to the museum’s Sully portrait of Patrick Henry. The technical challenges of painting young children must have been immense, but the resulting picture of a mother cradling her child at a very young age is charmingly natural.

Pre- and post-conservation details from Samuel Taylor’s 1837 portrait of Captain Thomas Trent Jr and his son William Henry Trent.

Barry said, “For this show, I’m particularly excited because we’re taking objects both from the fine and decorative arts collection of the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and the folk art collection of the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum. We have wonderful likenesses by self-taught artists.” She cited in particular the portraits of Charles Henry Robertson and Margaret Frances Osborne Robertson of Charlotte County in Virginia. They were painted by an unknown artist around 1825-30.

The exhibition planning prompted further conservation of portraits, old and new, so they could safely be put on display. Conservator Shelley Svoboda said, “Really, about half of the pictures needed some notable work. We’ve been very fortunate to have some Grainger Foundation funding that has helped us support the conservation needs of the show. We got a lot of things out on view with this added support, and we had some gallery lights put in the lab for our final review. It really helps a lot.”

Painted in oil on tulip poplar panels, the Robertson portraits had entered the collection in 2012, but had never been put on view due to their fragile condition. Svoboda explained, “Those are perfect examples of things that were acquired to fill a need in the collection, but their structure was so unstable that they literally had to be stored flat in boxes until we were able to stabilize them. The split in one of the wood panels was filled with wax that helped the panel appear intact. The frame and other elements keep the wooden structure together with the wax, making the surface look intact. The portraits in this show are largely on canvas, but we do have a number of wooden supports, and those pictures were probably the most needy or fragile.”

This image shows “Captain Thomas Trent Jr and his son William Henry Trent” before conservation. Painting by Samuel T. Taylor (circa 1800–46), Appomattox County, Va., 1837. Oil on canvas. Gift of Thomas R. Terry in memory of Joseph B. and Mary Featherston Terry, 2002.

Among the canvas portraits, there were several that had some challenging tears. Svoboda explained, “In the case of the Samuel T. Taylor paintings [circa 1800-40] of the Trent family, complex tears were found in those pictures, which had come into the collection in a largely untouched condition. The original integrity of the materials and artist’s techniques was very, very rich. For those pictures, techniques were chosen that were very low intervention, so that the integrity of the originals is retained. Those tears are locally treated with very small additions of tissues and reversible conservation adhesive that are largely invisible, so that when you look at the back of the paintings, they still have the original inscriptions largely visible. Those pictures get a more passive type insert rather than a lining.”

The conservator concluded, “You learn incrementally. The knowledge builds slowly and steadily, so you’re not having something placed in front of you that is beyond what you can professionally and responsibly take on. Things come in with unique and daunting conditions, but if we systematically go through the subsets of problems, we can solve them. I am fortunate to always see in the lab a real diversity in paintings, their styles, condition and places of origin. I learn a lot from this direct visual comparison – by seeing things next to each other. And one of the things I think this exhibition will do is bring some of this diversity to the visitor.”

From the most polished academic renditions to the most naïve capture of a sitter’s expression, the portraits in “Artists on the Move” reveal a common humanity that present viewers share with men and women who lived long ago.

The DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum is at 326 West Francis Street. For additional information, www.history.org/history/museums or 757-229-1000.

Journalist Karla Klein Albertson writes about decorative arts and design.