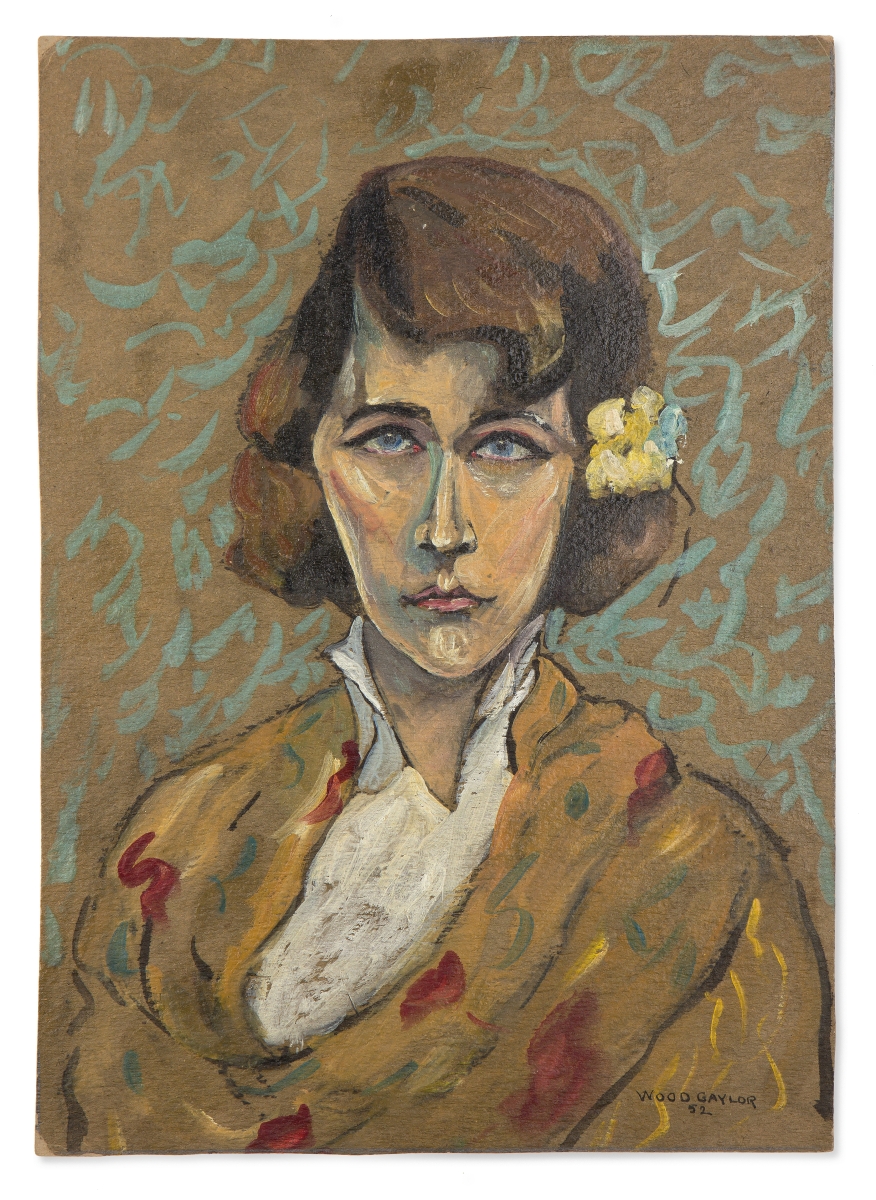

“Arts Ball, 1921” by Wood Gaylor (1883-1957), 1925. Oil on canvas, 14½ by 35¾ inches. Gift of Adelaide L. Gaylor, 1958. Ogunquit Museum of American Art.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

OGUNQUIT, MAINE – Those who consider themselves relatively knowledgeable about American art can be inclined to think of any artist they have never heard of before as a peripheral figure – even an “outsider.” But that problematic term would be doubly inappropriate for Wood Gaylor, who was in fact a consummate insider. His vibrant, witty, exuberant paintings are little remembered now, but in his day Gaylor occupied a privileged place inside the art world of early Twentieth Century America and later took on a leadership role in preserving its legacy. Nevertheless, there has never before been a monographic museum exhibition dedicated to Gaylor’s own distinct body of work – until now. “Art’s Ball: Wood Gaylor & American Modernism, 1913-1936” is on view at the Ogunquit Museum of American Art (OMAA) through October 31.

Wood Gaylor is a longtime interest of Andrea Rosen, curator at the Robert Hull Fleming Museum at the University of Vermont (UVM), which originated the exhibition. Early in her tenure at the Fleming, Rosen wrote about Gaylor’s “Dancing Lesson with Walt Kuhn” for an exhibition of work donated by UVM alumni. She remembers that the painting, which shows a rehearsal overseen by modernist artist Walt Kuhn for one of the infamous arts balls that he organized, “made me realize that Wood Gaylor was a really interesting figure, and there was a lot more that could be learned about him and a lot more that could be learned about the art world through his work.”

The Fleming has a wealth of work by Gaylor, thanks to a gift from his widow, Adelaide Lawson (an important artist in her own right), so the idea of a monographic exhibition quickly developed. It gained steam once both the OMAA and the Heckscher Museum of Art on Long Island, which also have important works by Gaylor, expressed enthusiasm for a tour. The tour debuted at the Fleming in early 2020 and was meant to travel from there to Ogunquit until the Covid-19 pandemic put those plans on hold. After a limited run at the Heckscher earlier this year, it has now returned to the OMAA a year later than originally planned.

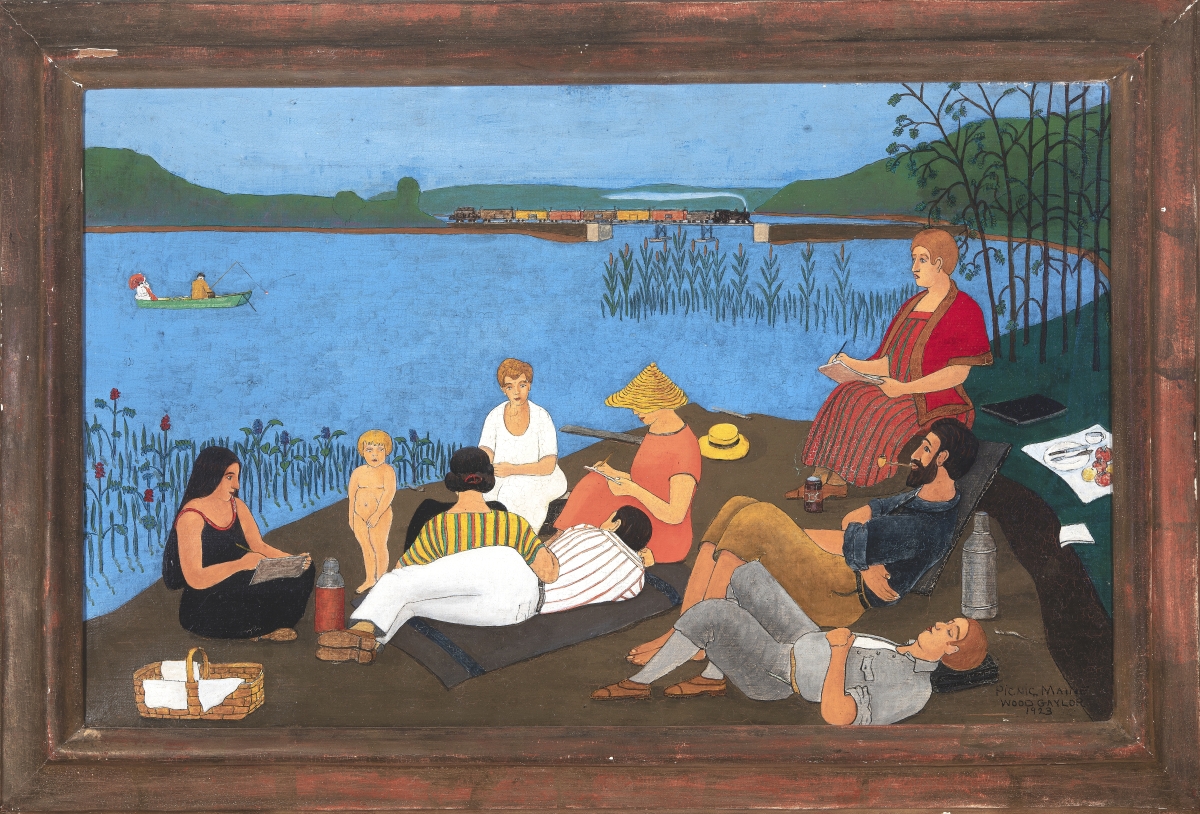

“Picnic At Shaker Lake” by Wood Gaylor (1883-1957). Courtesy of Bernard Goldberg Fine Arts, LLC, New York.

The paintings are unabashedly alluring, both visually and from a documentary perspective. Gaylor’s main subject was the art world parties that he attended and helped to organize, which were visual spectacles in and of themselves. Although his paintings are relatively modest in size, they burst with the color, wit and irreverence of these larger-than-life events. From guests and performers in costume and various states of undress to the outlandish props the performers used – life-size hobby horses, heads on sticks and a giant papier mache “Goo Goo Bird,” to name just a few – Gaylor captured it all. The paintings look like pure absurd fantasy, and in a sense they are, but they are also valuable historical records of these madcap revels that happened exactly as Gaylor saw and depicted them. Photographs of the Goo Goo Bird, the horses, even a faux wedding featured in a now-unlocated Gaylor painting (and at which Gaylor played the groomsman) all exist in Kuhn’s papers at the Archives of American Art, confirming the absolute accuracy of Gaylor’s depictions. Artists’ memoirs, including Gaylor’s own, also provide documentation of these arts balls.

Gaylor wrote his memoir later in life, while living a quieter existence on Long Island. Only about one-quarter of it, Rosen notes, relates directly to his time in the inner circle of the New York art world; the rest is less studied and was made available to the exhibition’s organizers largely through Wynn Gaylor, one of Wood Gaylor’s three sons with Lawson. As Wood Gaylor tells it, in what Rosen describes as his “folksy” style, his early life was difficult. His parents lived catch-as-catch-can, running saloons, racetracks and boardinghouses and moving every few years, first in Connecticut and then in New York City. As a result, Gaylor’s education was erratic, and he never graduated from high school. Instead, at age 17, he took a job at the Butterick Publishing Company, beginning a career as a pattern-maker for women’s clothes that would be his continuous day job for the next 50 years.

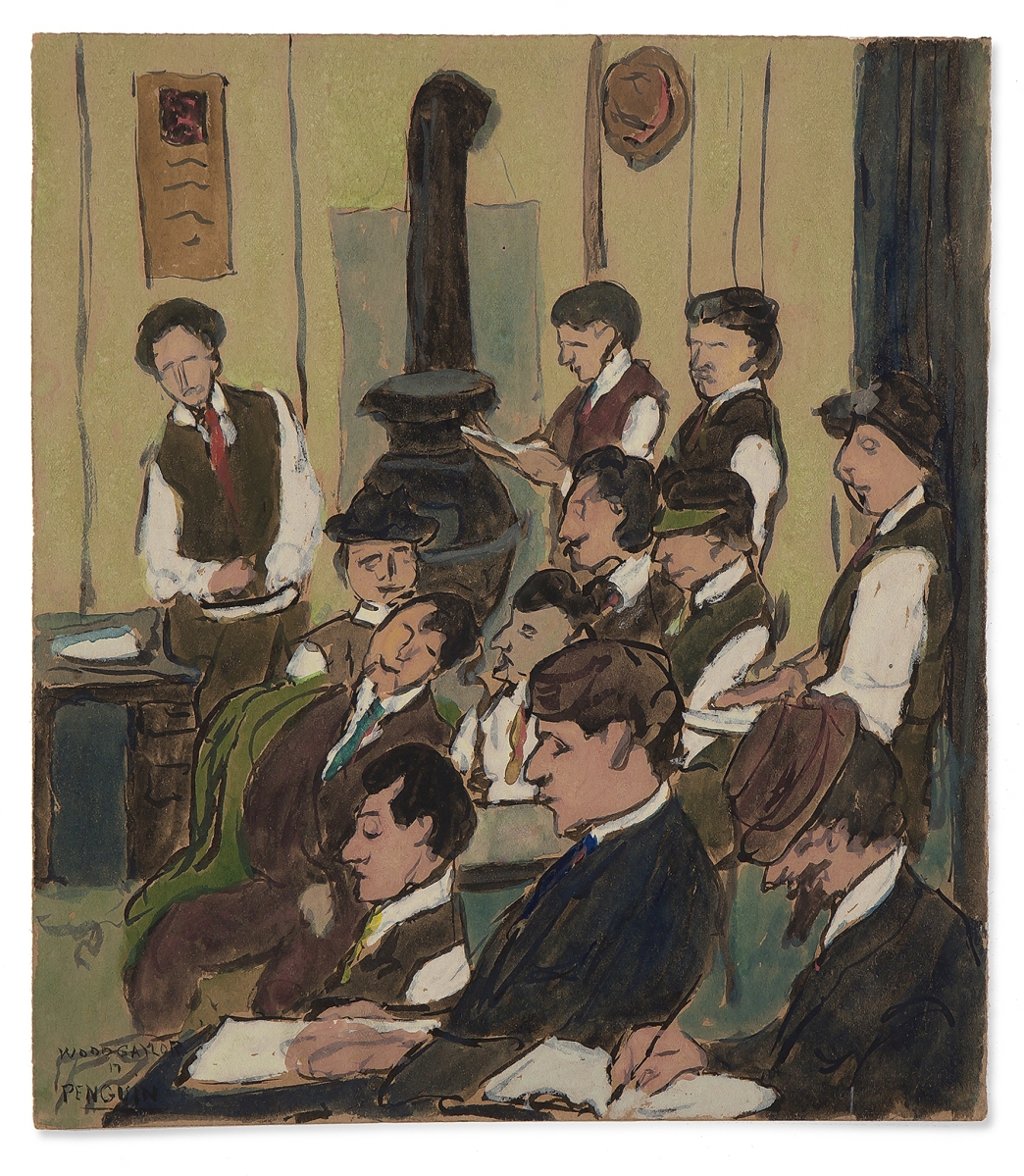

Having established himself as a professional man in the city, Gaylor also explored other interests, joining the National Guard and, notably, taking classes at the National Academy of Design. Connections there led him indirectly to a sketching group organized by Kuhn, who was at that moment hard at work on organizing the Armory Show, a groundbreaking exhibition of American and European Art that would rock the New York art world in 1913. Gaylor was immediately hooked; he and Kuhn became fast friends, and Gaylor not only helped with the Armory show but became an active member of the artist’s club known as “The Penguin,” which he fondly depicted in an early oil. The artist’s balls seen in the later works that Gaylor produced at the peak of his artistic career were innovations of the Penguin: dazzling, elaborate events whose ticket sales helped support the group’s exhibitions and other initiatives.

Installation photograph, “Art’s Ball: Wood Gaylor & American Modernism, 1913-1936” at the Ogunquit Museum of Art. Courtesy Ogunquit Museum of Art.

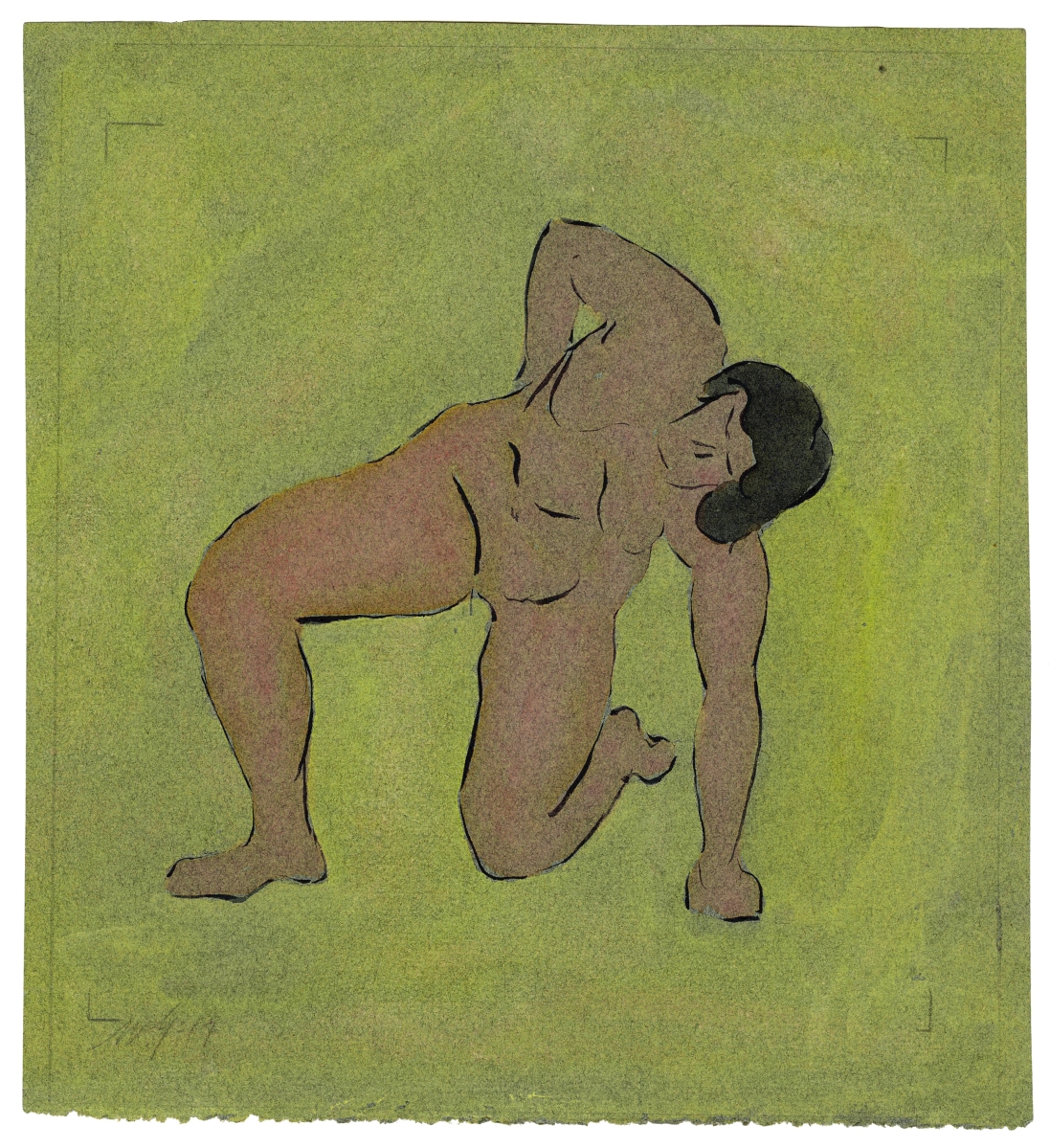

Women were active members of the groups to which Gaylor belonged – first the Penguin and then, after its demise, the Modern Artists of America and Salons of America, among others (in fact, he met Lawson through their mutual membership in the Penguin). Their presence gave him the opportunity to demonstrate his attentiveness to women’s fashions, evident in the variety of gowns and party dresses that female members wear in paintings like “K.H.M.’s [Kenneth Hayes Miller’s] Birthday Party” and “H.E.F. [Hamilton Easter Field] Auction,” as well as in the trimmed coats and stylish hats of “Off to Europe,” documenting an on-board send-off for artists Yasuo Kuniyoshi and Katherine Schmidt. But there were also ways in which this rarefied society was exclusively a boy’s club, with certain events open only to male members. Women are present, to be sure, in works like “Bob’s Party”; it’s just that they are not the artists’ colleagues and life partners, but instead the nude models who sat for their weekly sketching sessions, here taking on the role of prospective members of a harem for a king played by Walt Kuhn.

Costume was an essential part of such events, both the public ones for which tickets were sold and the more private ones like Bob’s Party; attendees’ costumes were evaluated at the door before admittance. At another male-only event, a dinner organized to honor the sculptor Constantin Brancusi, attendees dressed as, and took on the personae of, volunteer firefighters, dressed in uniform and carrying fire buckets and hoses. Participants even created faux portraits of each other as fire fighters to hang on the walls as decorations (Brancusi was reportedly a bit perplexed by it all). Other party themes frequently involved drag – the artist Louis Bouché, dressed as Salome, ultimately won the prime position in Kuhn’s harem – as well as “a lot of brownface; ethnic dress-up with these Orientalist themes,” Rosen says. “There’s a lot of really interesting gender dynamics and racial dynamics going on there.”

Such exoticizing tropes were common in early Twentieth Century America at all levels of society, but Rosen also connects it to the artists’ shared interests in developing a uniquely American art, one that drew influence from various “primitivisms.” The Pierrots and harlequins and sultans that they dressed as (there is also a “Pekin Cabaret” painting by Gaylor, not in the show) drew upon nativist tropes from Europe, the Middle East and Asia, but a close look at, for example, the OMAA’s own “Arts Ball 1921” reveals many attendees dressed as Indigenous Americans. This kind of “playing Indian,” Rosen says, “is a way to solidify a white American group identity…calling on a completely imagined version of what primitive American life was.”

“Union Square Fire Brigade” by Wood Gaylor (1883-1957), 1930. Oil on canvas, 16¼ by 37¼ inches. Portland Museum of Art, Maine. Hamilton Easter Field Art Foundation Collection, gift of Barn Gallery Associates, Inc., Ogunquit, Maine. Photo Melville McLean.

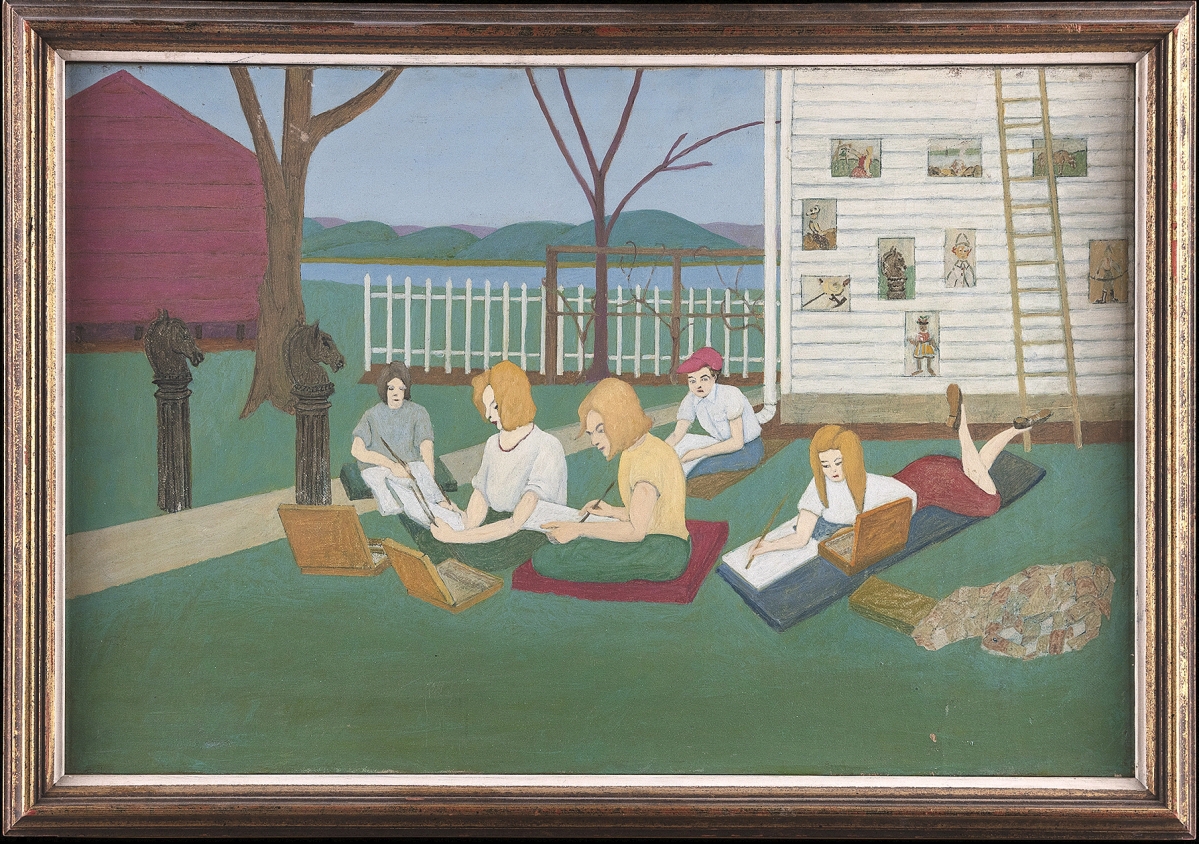

The interest in primitivism also came into play with a burgeoning interest in American folk art. Many in Gaylor’s New York circle attended the artist Hamilton Easter Field’s summer art school in Ogunquit, where artists lived and painted in repurposed fishing shacks furnished with the inexpensive antiques that were ubiquitous in that then-sleepy New England town. The artists became collectors, particularly Gaylor and Lawson, and the objects they collected later reappeared in their work – if not literally as decoys and weathervanes, then as the graphic forms and stark colors of, perhaps, the Goo Goo Bird or the enigmatic black-stockinged figure high above the crowd in “H.E.F. Auction.” Gaylor seems to have retained this interest in American folkways even after his later move to Long Island. “Potato Race” translates the revelry of the artists’ balls to a rural setting, and even “Painting Lesson on the Lawn,” depicting the summer art school he later ran with Lawson, includes horsehead hitching posts that both recall American folk art and allude to the hobbyhorses of his salad days in the city.

Perhaps partly because of his interest in folk art, Gaylor himself came to be seen as a “primitive” – in fact, shortly after his death, the gallerist Virginia Zabriskie showed his work in a 1960 exhibition titled “20th Century American Primitives.” It is true that his artistic training was unorthodox and that his style conveys the interest in line and bright color so often associated with the style we think of as “primitivism”; it is also true that some found him personally unsophisticated – Rosen recalls that Bouché described him as “not a very mature artist or a mature man.” But Gaylor’s lack of pretension was also an asset that, along with his talent, gained him access to the most closed circles of the New York art world. His “even-tempered pragmatism and likable personality,” writes catalog guest author Christine Isabelle Oaklander, made him indispensable to the more bellicose Kuhn, keeping many arts organizations and collaborations going longer than they might have otherwise. As evidence of this generosity of spirit, Gaylor’s own paintings regularly capture the artistic creations of his friends and colleagues – from Kuhn’s elaborate set pieces, to the firefighter portraits, to the posters the Penguin collaboratively produced for a post-World War I Red Cross initiative (“Posters,” 1920).

Long after he had effectively stopped painting, focusing instead on his day job and raising a family with Lawson, Gaylor remained a mover and shaker in the art world, serving on municipal committees and taking on a central role in forming a memorial collection for Field, who died in 1922. Unfortunately, even Gaylor’s diplomatic skills could not prevent the personality clashes that kept the newly formed Ogunquit museum from accepting the collection as a gift in the 1950s; it ultimately went to the nearby Portland Museum of Art, which is how that institution came to own “Union Square Fire Brigade.” The return of that painting, and others by Gaylor, to Ogunquit’s light-filled galleries – within view of where Gaylor, Field, Lawson, Kuhn, Bouché and so many others spent their summers painting the world through the windows of their fishing-shack studios – seems like something of a redress for that conflict of 70 years ago. Needless to say, today the OMAA is fully committed to honoring the legacy of that tight-knit artistic circle that Gaylor depicted in all its contentious, colorful craziness.

The Ogunquit Museum of American Art is at 543 Shore Road. For more information, 207-646-4909 or www.ogunquitmuseum.org.