Review and Photos by W.A. Demers

NEW YORK CITY — True to form, the 2016 edition of Asia Week New York offered a seemingly overwhelming schedule of gallery open houses, auctions, museum exhibitions, lectures and special events all geared around presenting the best in art and antiques from the vast continent of Asia. Good walking shoes were paramount. A lot easier on the feet, however, was the boutique presentation at Bohemian National Hall on March 11–15, known as the Asia Art Fair. With a small but representative roster of about 20 galleries and dealers, the five-day event opened with a preview reception from 5 to 9 pm on March 11, drawing collectors, museum curators, auction patrons and Asian arts enthusiasts in town for the week. It proved to be a convenient, comfortable and engaging spot for art collectors to gather and peruse ancient through contemporary Asian art in one location.

The fair traces its roots back to the earlier, now-defunct International Asia Art Fair by the Haughtons and Caskey-Lees’ Arts of Pacific Asia, which for a time produced editions on both the West and East Coasts. Many of the faces here are reminiscent of those larger productions, but there were also some new exhibitors, adding up to a showcase rich and diverse in its range of treasures from regions of China, Japan, Southeast Asia, Oceania, India and the Near East.

Paul Anavian, himself a gallerist, as well as managing director of the Manhattan Art & Antiques Center on Second Avenue, co-produced this show, now in its third year, with Bohemian National Hall’s director of events Michaela Boruta. Anavian said Asia Art Fair attracted about 1,200 visitors over its opening weekend, including the 500–600 who attended its Friday evening preview party. “There was actually a slight uptick in attendance,” said Anavian, “probably upwards of 2,000 over the run of the show and in the last couple of hours on the last day, many people returned.” Overseas buyers from China were in shorter supply this year, given the turmoil in that country’s art market in the past year, but “that was picked up by the American market,” said Anavian.

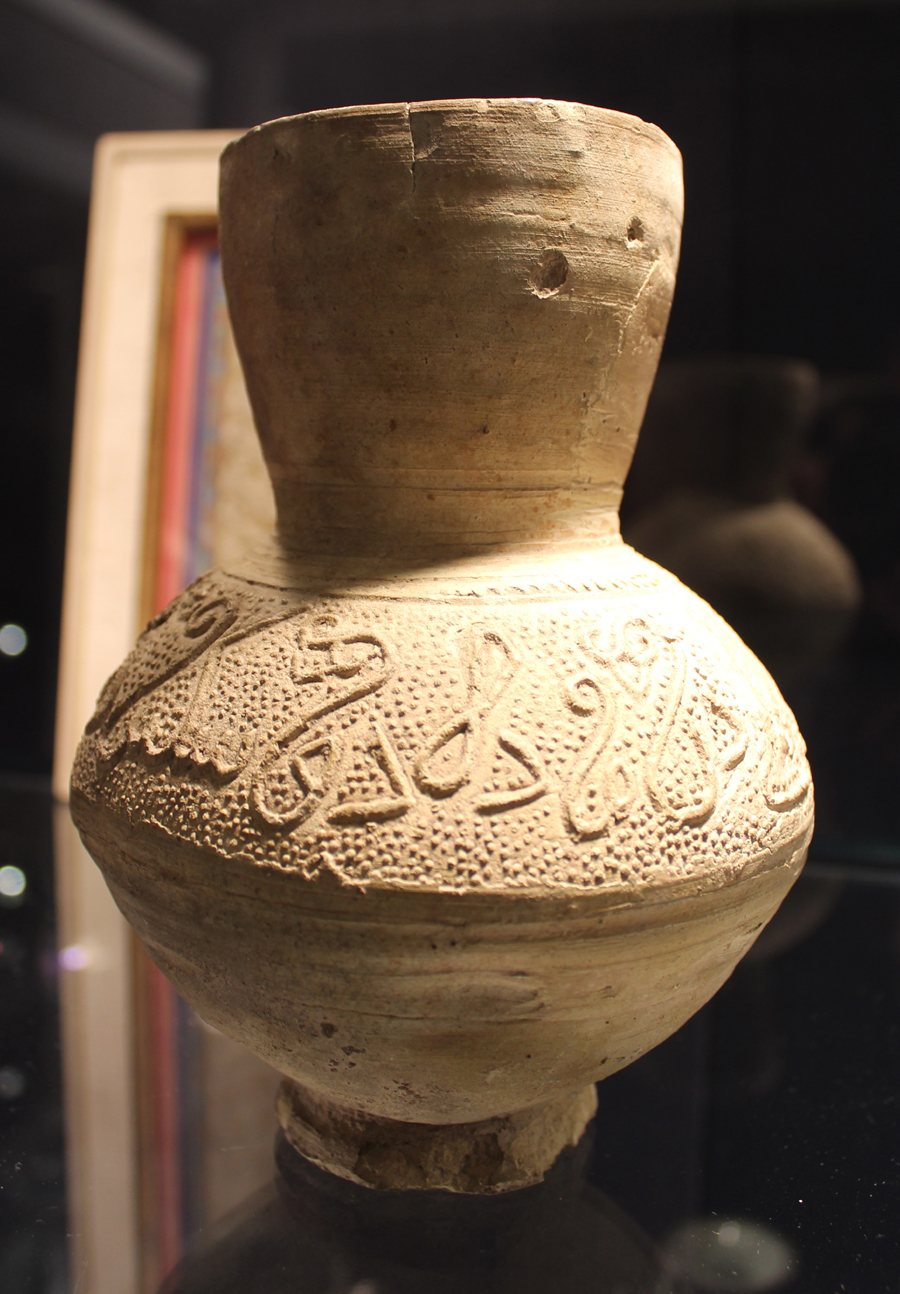

This Twelfth–Thirteenth Century unglazed ewer was a standout item at Anavian Gallery, New York City.

The New York dealer specializing in ancient Near Eastern and Islamic art also exhibited at the fair, featuring a Twelfth–Thirteenth Century Seljuk unglazed ewer, a blue and white porcelain Safavid bottle dating to the Seventeenth Century, a Ninth–Tenth Century silver armlet with feline head and a steel Mughal Koran box with gold inlay from the Seventeenth Century, among many other treasures.

One of the city’s top Asian art specialists, Moke Mokotoff Asian Arts, was at the fair with a rare Tibetan Ming silk banner of the seven precious elements of a Chakravartin (universal ruler). The piece featured gold brocade, embroidery and gilt animal membrane. It was made in the atelier of the 10th Karmapa and was being offered for sale to benefit a Tibetan monastery.

At Robyn Buntin of Honolulu Gallery, Hawaii, there were choice items such as a Seventeenth–Eighteenth Century huanghuali scholar’s chest stickered at $35,000, a Daoist temple piece from the Seventeenth Century and a Guanyin bodhisattva from the Ming period.

Michael Ayervais is a hairstylist, photographer and art dealer, who also fills his Manhattan apartment with hundreds of examples of traditional Japanese Ningyô dolls that were made in the Seventeenth through Nineteenth Centuries. One of these dolls, which, according to the dealer, has come out of an imperial household, joyfully greeted visitors to Ayervais’s booth. The circa 1800 figure stood (sat, rather) at 21 inches high, dressed in an embroidered green robe with orange piping and sash and featuring oyster shell lacquer over carved wood. The artist, Izukura, was active during the Edo period.

Standouts at Cost Mesa, Calif.-based Dharma Art included a brass plaque of a Buddhist mandala from Nepal, circa Seventeenth–Eighteenth Century, the center deity Amitayus Buddha representing long life. On a stand in front of the wall-hung mandala was a standing Varahi, Indo Tibet, circa Seventeenth Century, and on another wall in the booth hung a Tibetan painting with Ming silk brocade, Eighteenth–Nineteenth Century.

Korean traditional and contemporary art was paired in the booth of Donghwa Ode Gallery, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

Prominently featured on much of the fair’s marketing was a stately figure of a Gandharan bodhisattva, and no wonder. The Fourth–Fifth Century figure, 36¼ inches high, occupied an equally prominent spot in the booth of Lotus Gallery, an Austin, Texas-based firm that showcases Asian artistry ranging from the Han dynasty to contemporary fare. The stucco and polychrome Gandharan figure was a prime example of how the kingdom of Alexander the Great as it expanded into Asia brought Hellenistic influences to the region’s art.

Similarly, Manoli Tiliakos, co-owner of Pan Asia Art Gallery, Winchester, Mass., pointed out a smaller, exquisite “kin” of the Gandharan figure, this one a fine and sensitive portrait of Buddha in a head with clearly Hellenistic influences. Also on view here was a Chinese Ming period cast figure of Guanyin, unusual for the fact that the deity holds a baby Buddha on its lap.

Hellenistic features characterize this Gandharan bodhisattva, from the Fourth–Fifth Century. The 36¼-inch-high figure was prominently displayed in the booth of Lotus Gallery, Austin, Texas, as well as the fair’s promotional material.

Unusual, too, was the Kashmir influence seen in the facial features of a bronze Tibetan sculpture of a bodhisattva shown by Eleanor Abraham, a New York dealer who has placed important objects with major museums and has assisted with the development of numerous private collections. The Twelfth Century piece from western Tibet is one of three the dealer reported were under consideration following the show, the others being a Fifteenth–Sixteenth Century bronze Maitreya, the bodhisattva of loving kindness, and a large Shakyamuni from the Thirteenth–Fourteenth Century.

Asian textile art was abundant, especially that being offered by Hamid Tavakoli, a specialist in the genre. The dealer’s piece de resistance was not on view in his booth on the fifth floor of the hall, however. The monumental Chinese silk brocade thangka from the Eighteenth Century with the signature of the Qianlong emperor (1711–1799), the sixth emperor of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, greeted showgoers as they stepped out of the fourth floor elevator.

Appropriately, in this the Year of the Monkey, Stuart and Barbara Hilbert of the Jade Dragon, Ann Arbor, Mich., filled their booth with many examples of Sun Wukong, also known as the Monkey King, a mythological figure who features in a body of Chinese legend involving him getting into the imperial garden and stealing a peach. One of these was a small Ming dynasty jade from the Seventeenth Century. One of the largest jade bowls with a 9¾-inch diameter, was also on offer from the couple. “The opening was the best since the show began,” they reported afterward. “It was mobbed and the visitors were hungry to find something to buy. It was so busy that although there were three of us in our booth, we could not come close to answering all of our clients’ questions or showing all the things they wanted to handle and discuss. However, we believe that most dealers were very happy with their sales that evening; we certainly were.”

The Hilberts added that with Saturday’s competing showings, sales and dealer openings, however, it was relatively quiet. “Sunday through Monday found a number of serious buyers shopping the show,” they said. “Tuesday was perhaps the busiest apart from Friday’s opening with some returnees, and many new serious buyers. Overall, the dealers who did best were ones that had former clients from Washington to New Haven, including the greater New York area, and had sent out invitation passes to the show.”

The downside for those selling to Chinese clientele, which included the Hilberts, is that many Chinese did not come to New York this spring and those that did seemed to be a different group on the whole from previous years, according to the dealers. “They were mostly young Chinese ‘pickers,’ who were interested in taking photos and sending them back to Beijing, Shanghai or wherever in order to make a commission,” observed the Hilberts. “They were also very much tougher in their bargaining positions from the past. The downturn in Asia was quite apparent.”

For additional information www.theasiaartfair.com or 212-988-1733.