“Spirit Gates” by John T. Scott (American, 1940-2007), 1994. Aluminum. Gift of Premier Bank, 94.263. ©John T. Scott Artist Trust.

By Karla Klein Albertson

NEW ORLEANS, LA. – If the embedded image of New Orleans is a masked ball amid Rococo Revival furniture and silver-laden tables, “Atomic Number 13” will explode that screenplay forever. A compact exhibition at NOMA devoted to aluminum in Twentieth Century design explores the ornamental versatility of the light, strong element first isolated in the lab just over 150 years ago. From compotes to staplers, airplane wings to monumental sculpture, aluminum has fundamental advantages that has led to its widespread use for art and industry.

The New Orleans Museum of Art already had a permanent collection rich in Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century material, thanks to the efforts of well-known scholar John Keefe, the curator from 1983 until his death in 2011. When Mel Buchanan took up the title of RosaMary Curator of Decorative Arts and Design in 2013, she felt her directive was clear, as she explained in a recent conversation with Antiques and The Arts Weekly: “Take this great collection that NOMA is known for – that John Keefe built – and continue moving it forward in time. We’re not leaving behind the traditional collection – we’re moving the collection forward in time to include the Twentieth Century. And collecting contemporary design from the Twenty-First Century as well.”

As for the choice of this particular subject for a focus, Buchanan is quick to honor the previous work of Sarah Nichols for her exhibition, “Aluminum by Design,” at the Carnegie Museum of Art in 2000. Light metal enthusiasts can easily pick up the catalog online. But the NOMA show is drawn from the museum’s own permanent collection, which the curator needed time to build.

She continued, “This particular exhibition on aluminum is not something we could have presented ten years ago, because it reflects this inclusion of the Twentieth Century. A collection can’t be created overnight, so it’s still a work in progress but if you look closely at the credit lines of objects in this exhibition, you’ll see some strategic purchases and really wonderful gifts.”

An examination of the individual exhibits reveals some crucial acquisitions. Certainly the Nineteenth Century had great silver punch bowls, but partying did not end when 1900 rolled in to song and trumpets. A signature piece of “Atomic Number 13” is the Russel Wright “Saturn” punch bowl with orbiting cups, which entered the collection in 2017. At 30 inches in diameter, it looks capable of flight.

“Maximilian” lounge chair by John Vesey (American, 1925-1992), 1958 design. Wrought aluminum, steel mesh, original leather. New Orleans Museum of Art, Museum purchase, William McDonald Boles and Eva Carol Boles Fund.

A 2015 auction purchase brought the museum a 1958 “Maximilian” lounge chair with aluminum frame and leather seat designed by John Vesey (1925-1992). As the curator points out, the profile immediately invites comparison with the early Nineteenth Century campeche lounge chairs so prized at auction.

Other objects came from a donation by noted collector Dr Ronald Swartz and his recently deceased wife, Ellen Johnson. Rolling service carts were must-have accessories in midcentury entertaining for everything from drinks to the arrival of the Christmas ham. Keeping it light for air service, Frantz Industries designed a sleek early version for use on the Douglas DC3 aircraft; NOMA received this gift from the collection in 2018.

Many museums received material from the George R. Kravis II collection of Tulsa, Okla. – the Cooper Hewitt, MoMA and New Orleans among them. See more of the collection in 100 Designs for the Modern World: Kravis Design Center by Penny Sparke. But on display in this show are two gifts that sum up aluminum’s utility. The 1949 Wilson-Jones stapler may earn that essential gadget a better spot on the desk. Industrial design, in this case by Herbert W. Marano (1907-2001), is still design.

Another Kravis collection gift is the elegant aluminum and glass footed Stratford Compote, designed by Lurelle Guild (1898-1985) around 1934 as part of an Art Deco tableware line. In its early decades, aluminum was considered a luxury material. This was demonstrated when the curator discovered the oldest exhibit in the show by a diligent search in NOMA’s own inventory.

Stratford compote manufactured by Aluminum Company of American (Alcoa), designed by Lurelle Guild (American, 1898-1986), circa 1934. Aluminum, glass. New Orleans Museum of Art, Gift from the George R. Kravis II Collection, 2019.8.24. ©Alcoa Inc.

“I started looking through our historic collection and discovered the piece of Viennese glass from the “Indian Series” by J.&L. Lobmeyr. Being able to pull this glass from the 1880s and use it in this Twentieth Century story was a critical chapter in showing the evolution of aluminum from being a rare metal used like gold for decoration.” The discovery of technology that allowed large amounts of aluminum to be more easily produced opened up the material for increased industrial deployment although its attraction for artists never ceased.

The chemical details of aluminum extraction are best left to scientific journals, but the show does have a series of factory images by ground-breaking photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White (1904-1971). These were taken in the 1930s at the Alcoa – Aluminum Company of America – plant in Pittsburgh and illustrate the metal’s processing from mining to actual production to promoting finished products for household and recreation use.

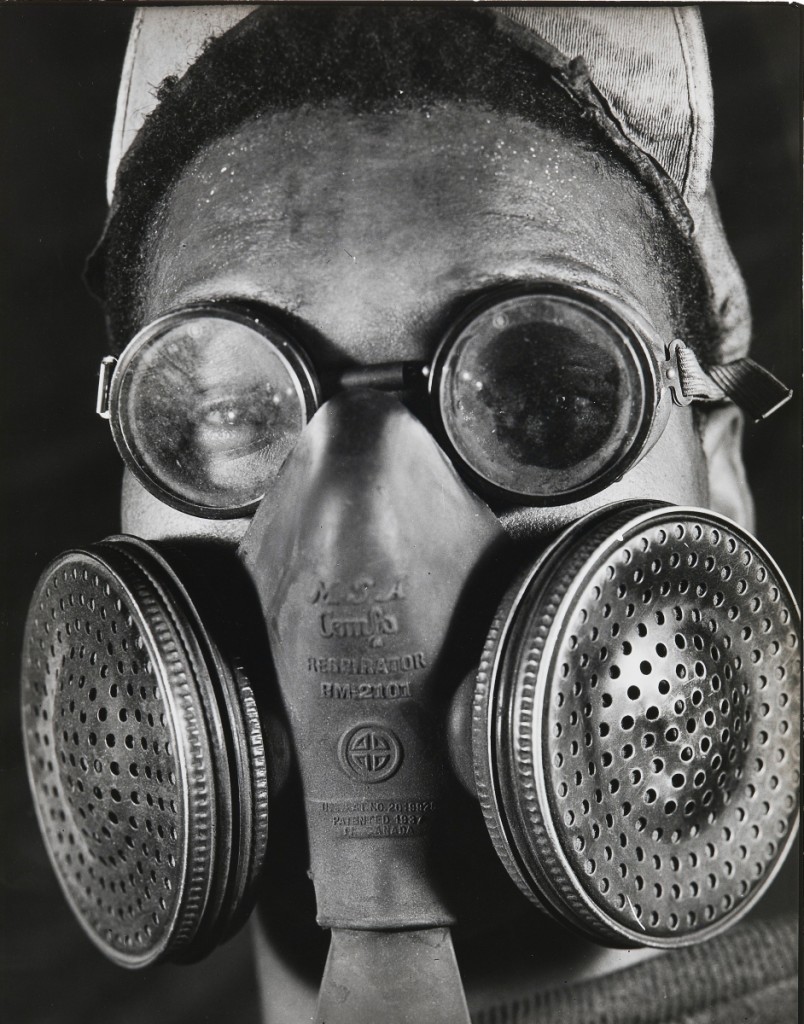

Most striking is the 1939 “Portrait of Louis Klinkscales,” a workman in protective mask and goggles who looks like the captain of a Steampunk airship. In actuality, it reminds us of the real dangers faced by the people involved with the industrial process of making aluminum.

“Aluminum Company of America, Portrait of Louis Klinkscales” by Margaret Bourke-White (American, 1904-1971), 1939. Gelatin silver print. New Orleans Museum of Art, Museum purchase, General Acquisitions Fund, 79.38.

In summary, Mel Buchanan stressed what she hopes visitors will take away from “Atomic Number 13”: “Museums shouldn’t always be about rarified art. I think they’re about teaching us to look all around us, whether that’s an exquisite art sculpture in the garden or giving that same attention to objects we live with. Because everything has craftsmanship and meaning and symbolism and memories tied up in it. This is one small show where you can get to the heart of why, I think, art museums are important.”

While these small works of art fill an interior gallery, visitors must step outside the museum door to see the largest aluminum works of art in the NOMA collection. Permanently integrated into the building structure are the monumental “Spirit Gates” by John T. Scott (1940-2007), an influential New Orleans sculptor and MacArthur Fellow, who taught for many years at Xavier University in the city.

Not far away, among more than 90 art works in the Sydney and Walda Besthoff Sculpture Garden on the museum grounds, aluminum is used for Claes Oldenburg’s “Corridor Pin, Blue,” Lin Emery’s “Wave,” Robert Indiana’s “LOVE,” George Rodrigue’s Blue Dog “We Stand Together,” and Frank Stella’s “Alu Truss Star.”

“Atomic Number 13: Aluminum in 20th-Century Design” runs through April 17. The New Orleans Museum of Art is at 1 Collins Diboll Circle, right next to Big Lake, in the 1300-acre City Park. For more information, www.noma.org or 504-658-4100