vmfa_awaken-76_aam-2017-44-1024x959.jpg)

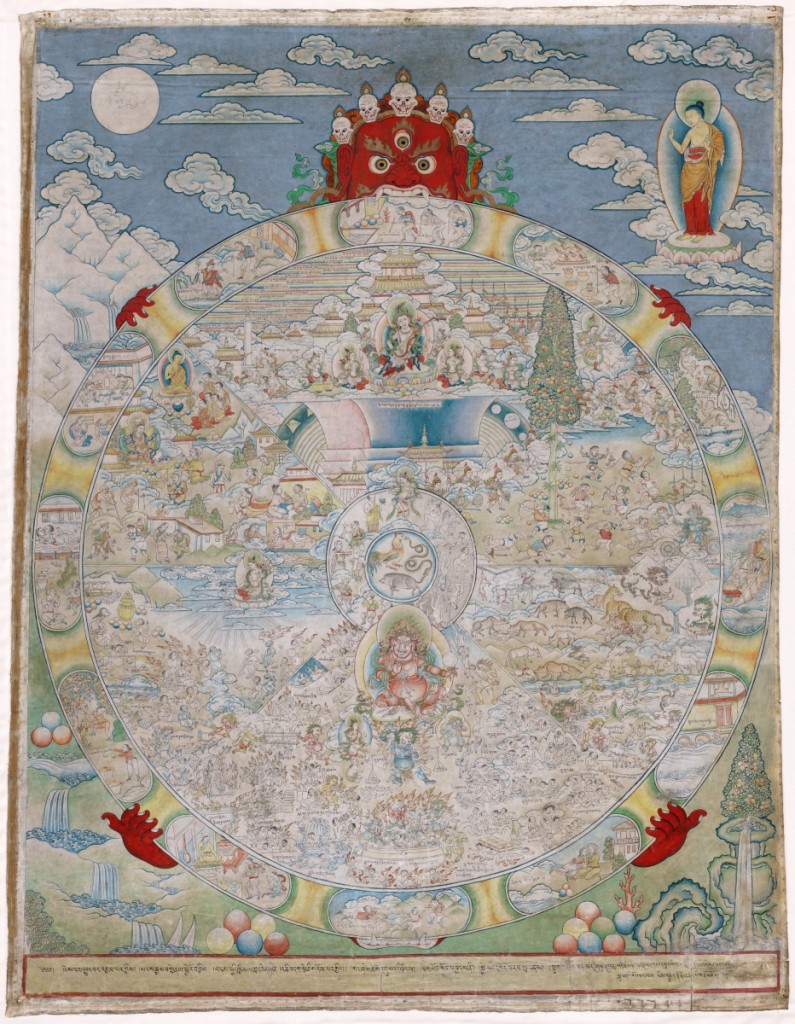

“The Melt,” 2017, Tsherin Sherpa (Nepalese, b 1968), acrylic, ink and gold on canvas. Asian Art Museum of San Francisco ©Tsherin Sherpa. Photo ©Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

By Karla Klein Albertson

RICHMOND, Va. – Interpreting art can be a dangerous pursuit. A Nineteenth Century portrait of a woman and her favorite horse can be fairly straightforward, while a medieval painting of the same two creatures might be fraught with symbolism. And then there is Tibetan religious imagery, filled with paths and doors – not to the next room – but far beyond to an expanded view of the universe.

A new exhibition – “Awaken: A Tibetan Buddhist Journey Toward Enlightenment” – which opened in Richmond at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts (VMFA) at the end of April and continues through August 18 – tackles the thorny problem head on. “With its vast pantheon of multi-limbed divinities inhabiting complicated geometric diagrams and corpse-strewn funeral grounds, Tibetan Buddhist art can be intimidating.” That bold admission leads off the essential catalog that accompanies the show. The co-curators and authors are Dr John Henry Rice, the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter curator of South Asian and Islamic art at the VMFA, and Dr Jeffrey Durham, associate curator of Himalayan art at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco.

Not only have they undertaken to present a branch of religious art with complex influences and iconography, they have tried to achieve the challenging goal of drawing visitors into a path of personal discovery. The paintings and artifacts used to illuminate the show’s master design – about 90 in all – are drawn principally from those two stellar collections at opposite sides of the United States. After its allotted time in Virginia, the exhibition will travel to the West Coast for a January 17-April 19, 2020, run at the Asian Art Museum.

Buddhism came to Tibet from India in the Seventh Century and became the official religion of the country under King Trisong Detsen (742-797), who hoped it would unite his people. Buddhist scholars came to teach, and Sanskrit texts were translated into Tibetan. The Tibetans practice a form of Buddhism known as Vajrayana, the “lightning vehicle” or quicker path to enlightenment. And an important part of this fast track was the ability of art works and visual concepts to aid or even activate the practitioner. The exhibition’s accompanying volume not only provides detailed information on the exhibits but also traces the history of Buddhism and its arrival and establishment in Tibet.

Although much can be learned from that excellent catalog, there are special benefits to experiencing this particular exhibition in person and walking through the ten spaces that address specific points on the path to enlightenment. Tibetan Buddhism requires deep study, but the ultimate goal lies beyond what any amount of book learning can supply. This may explain why the show’s title begins with the word “Awaken.” The making of art can be an end in itself, but in this case the works of art provide guideposts for a much longer journey.

In the catalog preface, Rice and Durham state: “Tibetan Buddhist art is meant to catalyze awakening, and the exhibition this catalog accompanies aspires to give visitors glimpses of the insights that these artworks conceal and reveal. Structured as a virtual journey, it moves from the confusion and dissatisfaction of ordinary consciousness toward the clarity of more focused, integrated and wakeful states of awareness.” In the modern world where we are surrounded by a thousand forms of distraction and improved focus often seems out of reach, any art that could change our consciousness is precious indeed.

In the catalog preface, Rice and Durham state: “Tibetan Buddhist art is meant to catalyze awakening, and the exhibition this catalog accompanies aspires to give visitors glimpses of the insights that these artworks conceal and reveal. Structured as a virtual journey, it moves from the confusion and dissatisfaction of ordinary consciousness toward the clarity of more focused, integrated and wakeful states of awareness.” In the modern world where we are surrounded by a thousand forms of distraction and improved focus often seems out of reach, any art that could change our consciousness is precious indeed.

In conversation with Antiques and The Arts Weekly, Dr Rice expanded on the exhibition’s primary goals, one of which is making the public more aware of the VMFA holdings in Himalayan art: “It’s one of the finest collections in North America. Even my colleagues have a hard time wrapping their heads around that, because it’s in the middle of Virginia. That was one of the driving goals, but then taking that material and making it accessible is the trick. The way Jeffrey Durham and I have co-curated this exhibition is that we have attempted to take this notoriously dense, complex, esoteric material to the public. We thought the best way to do that would be through storytelling, so we narrativized the material so we could tell a story with it. And, on top of that, invite the visitor to be not only a typical museum viewer but to be an actual participant in the story we are telling. As stated in the title of the exhibition, we extend an invitation to wake up, to go on a journey toward awakening.”

Rice went on to describe the intriguing way in which the exhibition presents the material: “Where we begin this story is with the here and now. The first gallery you walk into is not an orientation to Tibetan culture, it’s a kind of in-your-face presentation of what current, everyday life is. The entire room is filled with video and audio and mirrors, discontinuous mirrors, so you have these fragmented visions of mundane stuff. Everything from fancy cars and war, stock market tickers and crowds are in this chaotic presentation. This is where you are right now, this is ordinary life. We try to make the entire telling so engaging and first person that we’re not compelled to give you all of the historical, contextual background. We try to keep this about you, the visitor. I don’t want to give you the sense that the show is devoid of historical context – we give plenty of it – but we try not to give too much at one time.”

“After you’ve gotten past that chaotic blip of the here and now, you’re introduced to the Buddha and these ideas that offer a possibility for a release from that cyclic, unsatisfactory existence. Then there’s a big gallery that gives you the religious background; we take you from the historical Buddha up to Tibetan Buddhism with about 18 objects to get you through a thousand years of Buddhist history. Then there’s another section where you meet a teacher – you’re going to need your own lama, so we give you one – through a painting of a Fifteenth Century lama who will be your guide for the journey ahead. In this big gallery, he presents you with material that equips you for that journey. He introduces you to allies – some bodhisattvas and some female deities, such as Tara and the dakinis. And then he crucially presents you with a map and that is a particular mandala, a Vajrabhairava mandala from the Ngor Monastery in Tibet that will be your map for the meditative journey ahead.”

As can be deduced from the illustrations, Tibetan art is rich in figural sculpture of metal or wood and paintings. Large-scale paintings covered the walls of Tibetan temples and monasteries; the small-scale paintings on view in the exhibition are often on cloth. While they may be straightforward portraits of deities and holy teachers, other images called mandalas seem to represent maps but are actually charts for your spiritual practice. There is a video online from the Asian Art museum, where Jeffrey Durham explains, “What is a Mandala?” Literally, it means a palace with a divinity, while visually it appears to be a set of nested squares and circles at the center of which is that divinity. On a spiritual level, the mandala is a meditative environment where you hold the image in the mind’s eye. Like a picture that shifts when you view it from another angle, Tibetan art shifts the consciousness from the exotic visuals to the esoteric meaning behind them.

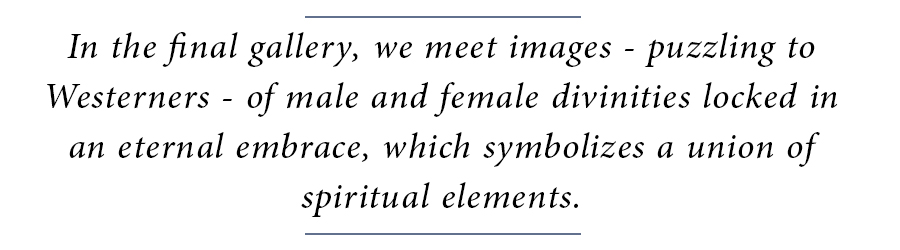

“Wheel of Life,” circa 1800, Tibetan, Eastern Tibet, opaque watercolor on cloth. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Richmond Zimmerman family collection, Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund. Photo ©Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Tibetan art abounds in female deities, such as Tara mentioned above. Some are a peaceful vision of the divine mother, while others are more fearsome figures, which the catalog describes as “edgy, wrathful goddesses who know the Vajrayana’s shortcuts toward the eventual goal.” In the final gallery, we meet images – puzzling to Westerners – of male and female divinities locked in an eternal embrace, which symbolizes a union of spiritual elements. From his West Coast office, Dr Durham explained the reason that this imagery is used: “Philosophically and fundamentally, it is because that is our most intuitive experience of what it’s like to be one being and then have your own identity at the same time. The Tibetan tradition takes that type of archetypal imagery and employs it to make us understand what nonduality might be like.”

In conclusion, Durham stressed, “We want to excite your curiosity and give you an experience that is different than most museums practice. The whole idea, in traditional museum practice, is to create the illusion that we know what’s going on, we have the final answer. But this exhibition is designed to be a ‘lived’ experience, as opposed to a dead experience. By and large, the exhibition should be a journey that you can take without having to go through the typical museum experience where you read, read, read and try to remember all that while you look at the object. We want you to have fun. The takeaway should be an awareness that the world that we live in is more wonderful than we imagine, because that is the antidote to our ordinary reality with all of its endless round of nonsense. There is more to this than meets the eye. The horizons of experience are wide open, if we will just open our eyes and see the common humanity there.”

Note that not all the images come from the distant past. The exhibition includes contemporary acrylic paintings by Nepalese artist Tsherin Sherpa (b 1968), which present new interpretations of traditional iconography. Also in the VMFA galleries May 2-5, a group of Tibetan monks from the Drepung Loseling Monastery will create a complex sand mandala that will be dismantled in early August.

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts is at 200 North Arthur Ashe Boulevard. For more information, www.vmfa.museum or 804-340-1405.

Journalist Karla Klein Albertson writes about decorative arts and design.

vmfa_awaken-60_aam-b63d5-mc10968.jpg)

vmfa_awaken-76_aam-2017-44.jpg)