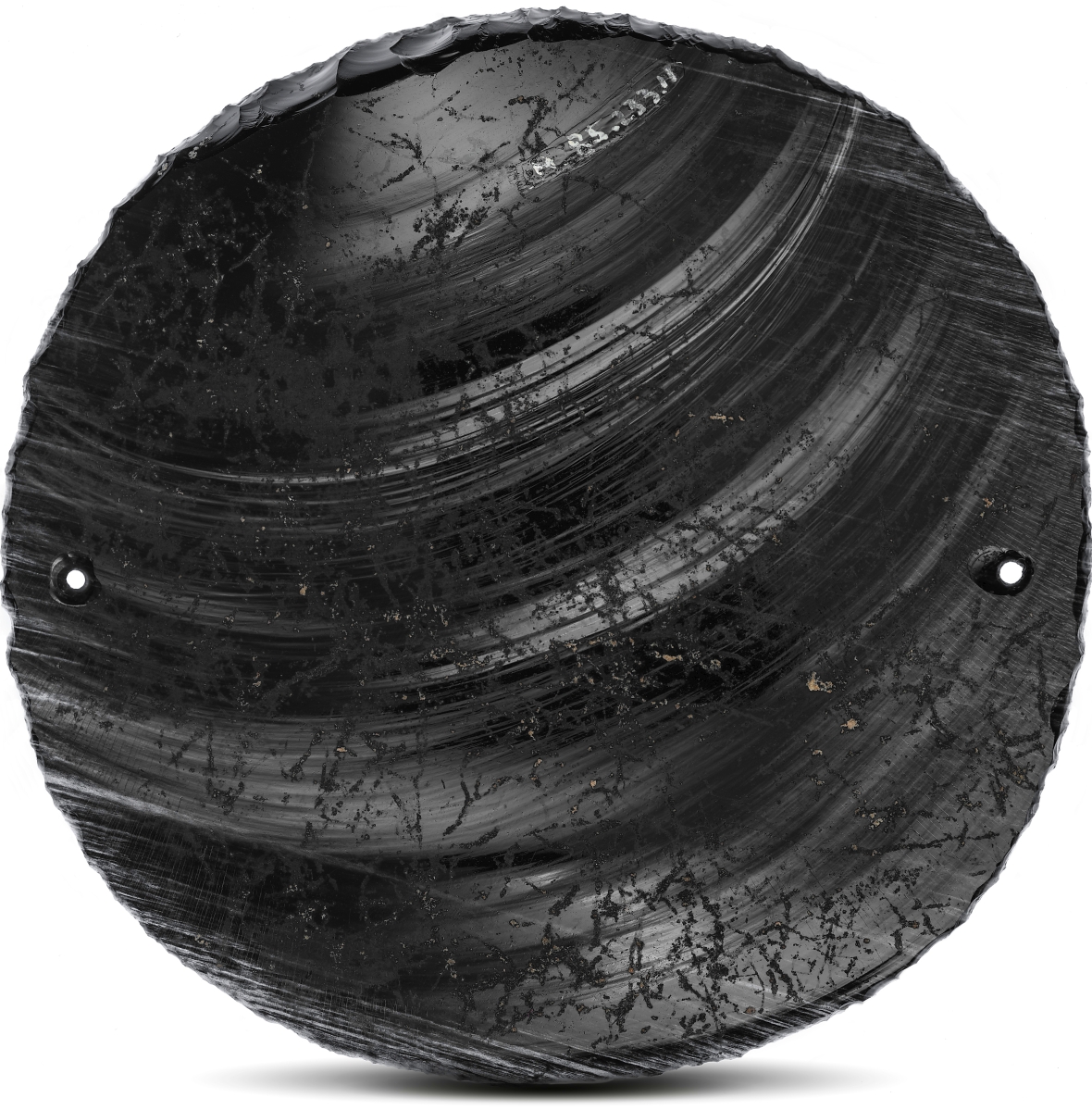

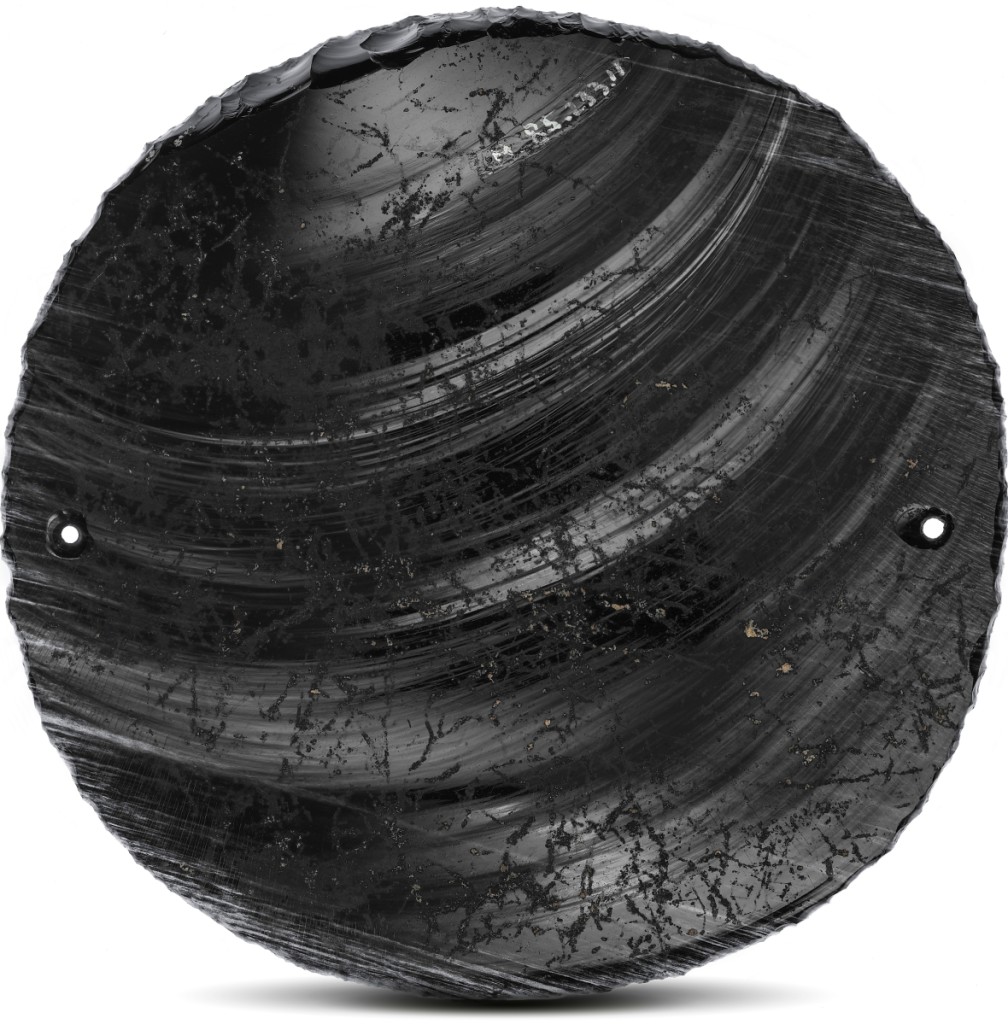

Mirror, Aztec, 1325-1521. Obsidian. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, gift of Constance McCormick Fearing. Photo ©Museum Associates / LACMA.

By James D. Balestrieri

LOS ANGELES – “Mixpantli: Space, Time, and the Indigenous Origins of Mexico” and “Mixpantli: Contemporary Echoes,” two complementary exhibitions now on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) represent clashes of cultures. Indigenous and Spanish in the Sixteenth Century, and in the present as the issue of immigration from Mexico and Latin America to the United States continues to be a cultural flashpoint. Half a millennium ago, in 1521, Tenochtitlán, capital of the Mexica (Aztec) Empire, fell to the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés and his troops. Tenochtitlán would become Mexico City, the capital of New Spain and the central urban nexus of modern-day Mexico.

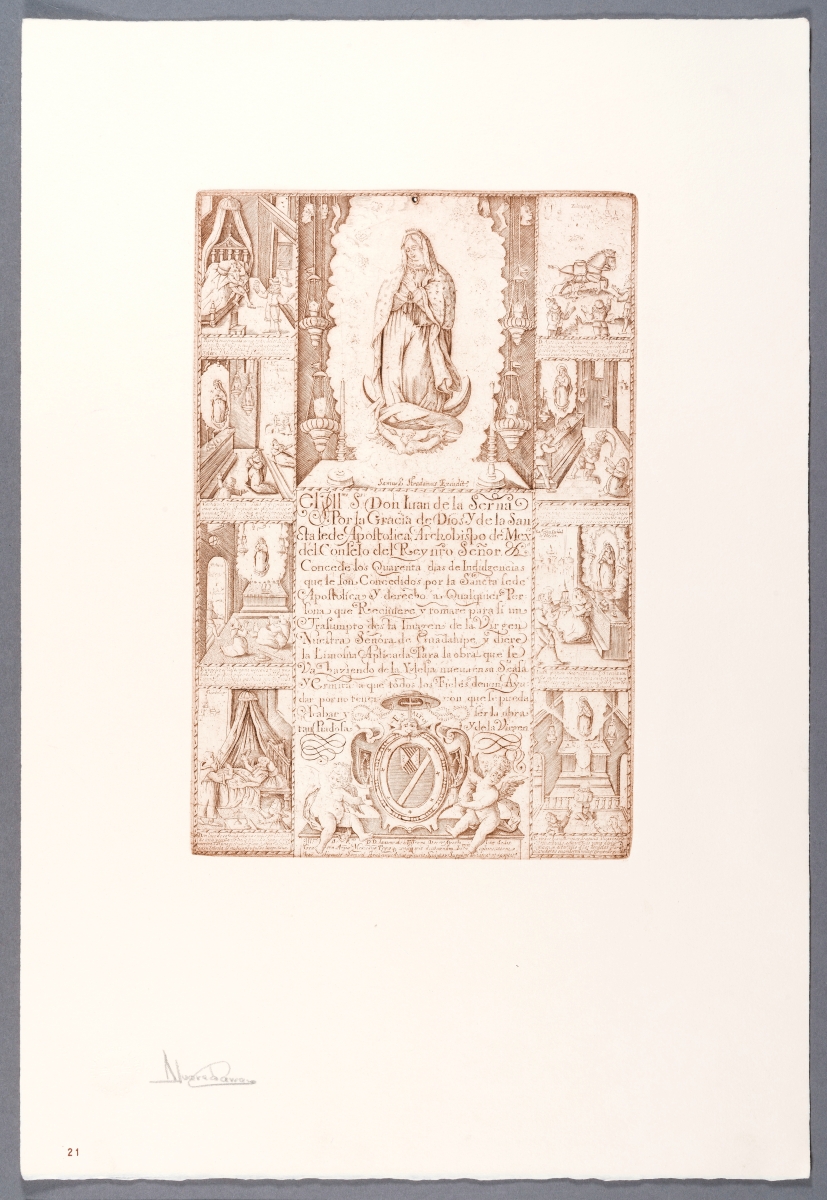

“Mixpantli: Space, Time, and the Indigenous Origins of Mexico” “subverts the traditional narrative of conquest by centering the creative resilience of Indigenous artists, mapmakers and storytellers who forged new futures and made their world anew through artistic practice. Nahua scribes and painters gave the name mixpantli or “banner of clouds” to the first omen of conquest, depicting this omen as both a Mexica, or Aztec, battle standard, and a Euro-Christian column enveloped in clouds. Mixpantli, then, reflects the bringing together of both Nahua and Christian worldviews, and the efforts of Indigenous peoples to reorient space and time in a new world and era. This show puts early colonial art in conversation with pre-Columbian artifacts to showcase the deeply Indigenous worldviews that shaped early Mexico.”

The companion exhibition, “Mixpantli: Contemporary Echoes,” by comparison and contrast, “showcases the lasting impact of Indigenous creative resilience and connects the vibrant artistic traditions of the past and present, of Los Angeles and Mexico. The exhibition features the works of contemporary artists and mapmakers who draw on Indigenous cartographic and artistic histories to challenge dominant narratives about place and belonging.”

These two descriptions from LACMA are worth quoting at length because they underscore the central truth that, in essence, these exhibitions are about maps – maps that represent competing visions of the same physical, geographical spaces. Maps of earth mark property and ownership; maps of the cosmos – of the cosmogony of realms – mark origins, heroic and tragic stories, and destinations, both physical and metaphysical.

Installation view of “Mixpantli: Space, Time, and the Indigenous Origins of Mexico” on through May 1, 2022 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Photo ©Museum Associates/LACMA.

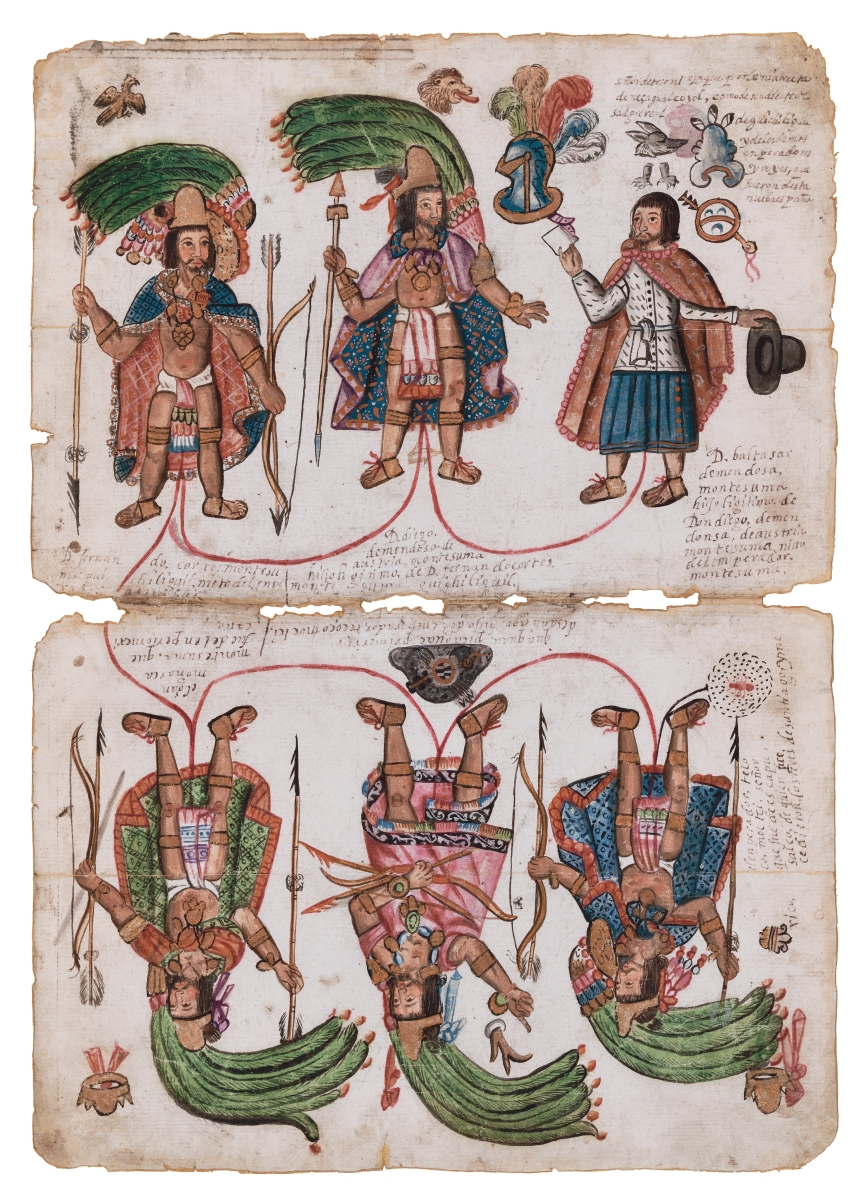

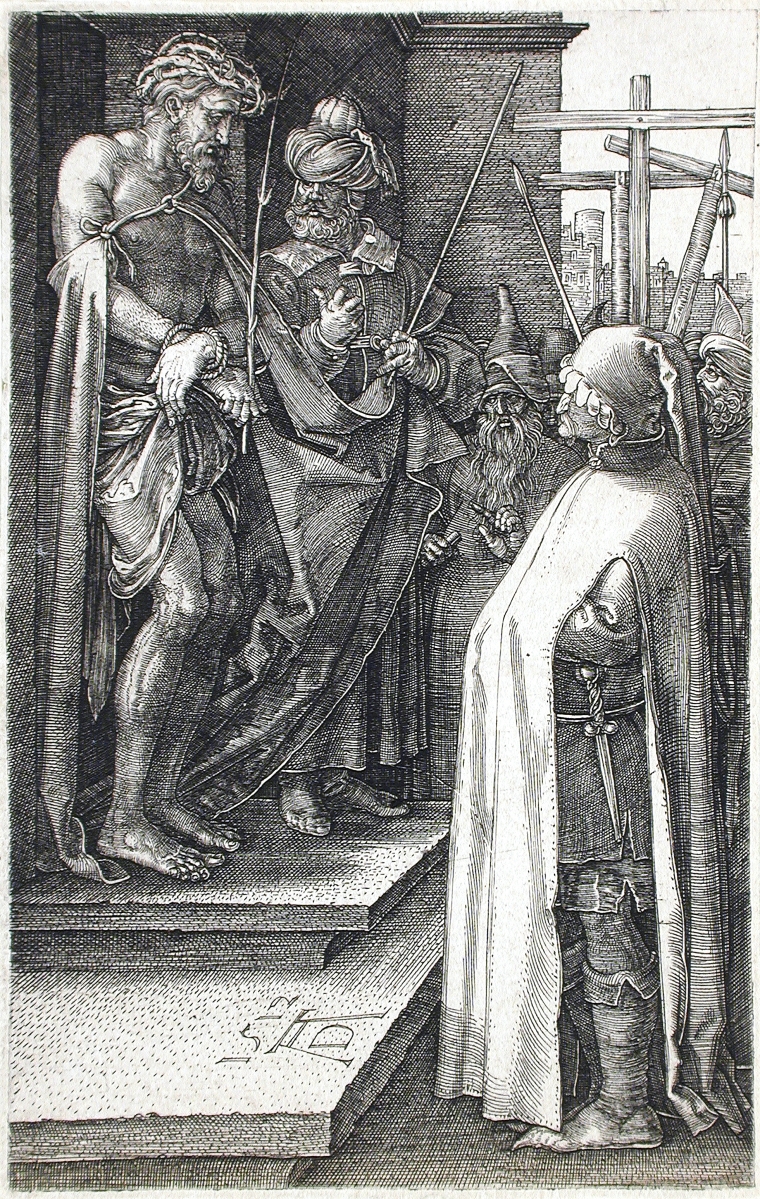

One way to acknowledge the new reality of conquest without acknowledging defeat is to read your sacred texts, histories and maps, both as prophecies that assimilate the conquerors and as tools that can be used to stave off land and power grabs. For instance, Indigenous artists, seeing Albrecht Dürer’s 1512 woodcut of the suffering Christ, “Ecce Homo,” adapt Christian iconography to the death of Moctezuma and add Christ as a “new solar deity in Nahua worldview.” As written in the bilingual (Spanish and Nahuatl) Florentine Codex, seven signs portended the downfall of Moctezuma and Mexica. The seventh was a bird with a mirror on its forehead, brought to the Emperor by some fisherman. Moctezuma is said to have seen a reflection in that obsidian mirror – perhaps one very much like that on display in “Mixpantli” – that showed the coming of mounted men.

At the same time, Indigenous scribes suggested that Moctezuma’s death and the arrival of the Spanish was preordained. Moctezuma’s last act, in these texts, was to counsel peace and welcome the Spaniards. In one account, his subjects stone him to death because he will not take up arms; in another, the Spanish, having imprisoned him, kill him when they see he has lost his power over his subjects. In both versions, Moctezuma sees the inevitable, tries to avert war, and sacrifices himself. The parallels to the passion of Christ are many and, in this scenario, invasion and colonization becomes instead part of the 52-year Nahua historical cycle, one that will ultimately lead to the restoration of the Aztecs to power in an echo of Christian resurrection.

The exhibition places this in context: “In Mesoamerican worldview, the cosmos have been created, destroyed and remade in cyclical fashion. The destruction of an era meant the sky would collapse upon the earth, and reordering cosmic space-time required divine sacrifice. To lift the sky, deities would raise a world tree at the four corners of the cosmos and its center, a five-directional order held sacred across Mesoamerica. These trees would once again sustain the three levels of the cosmos: the celestial, earthly and watery realms. Finally, a new sun, chosen through divine trial, would take his place in the skies, propelling time forward with his daily journey through the sky and his nightly journey through the primordial sea.”

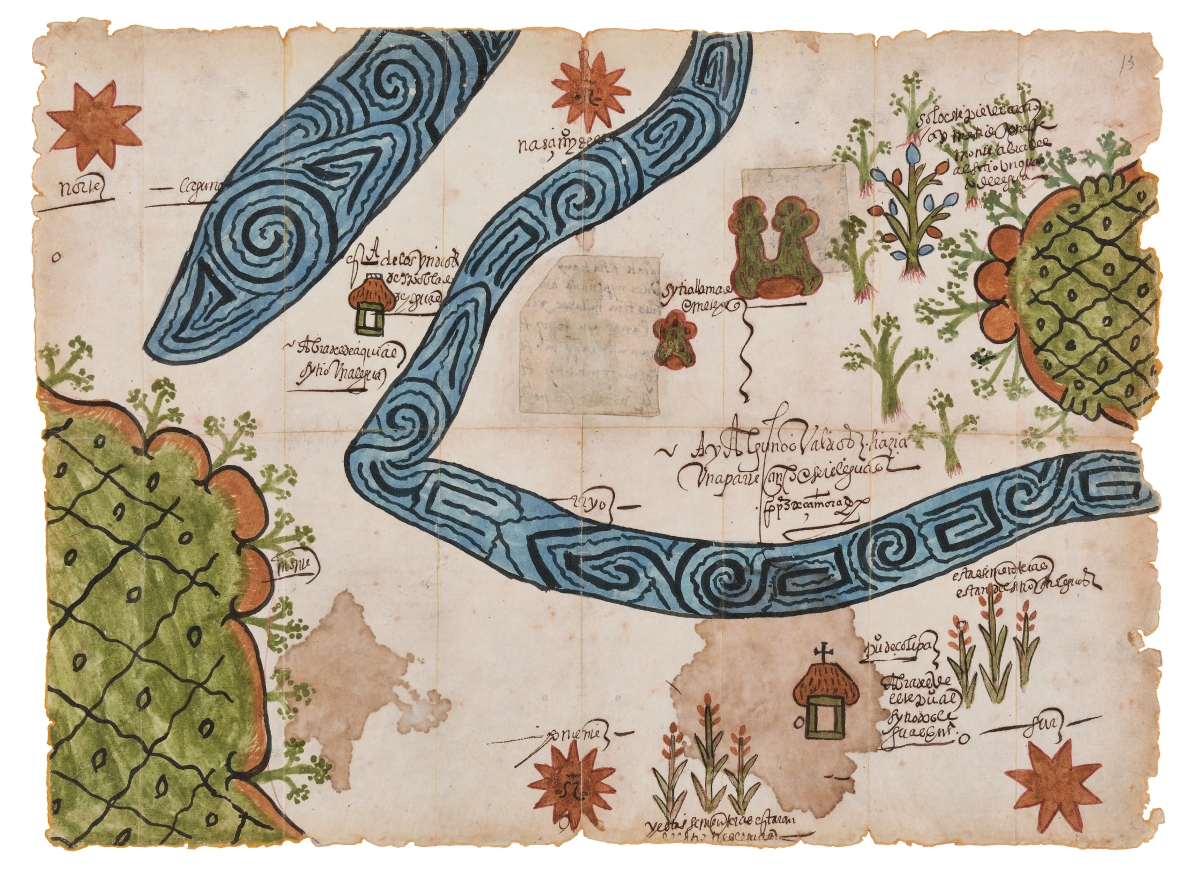

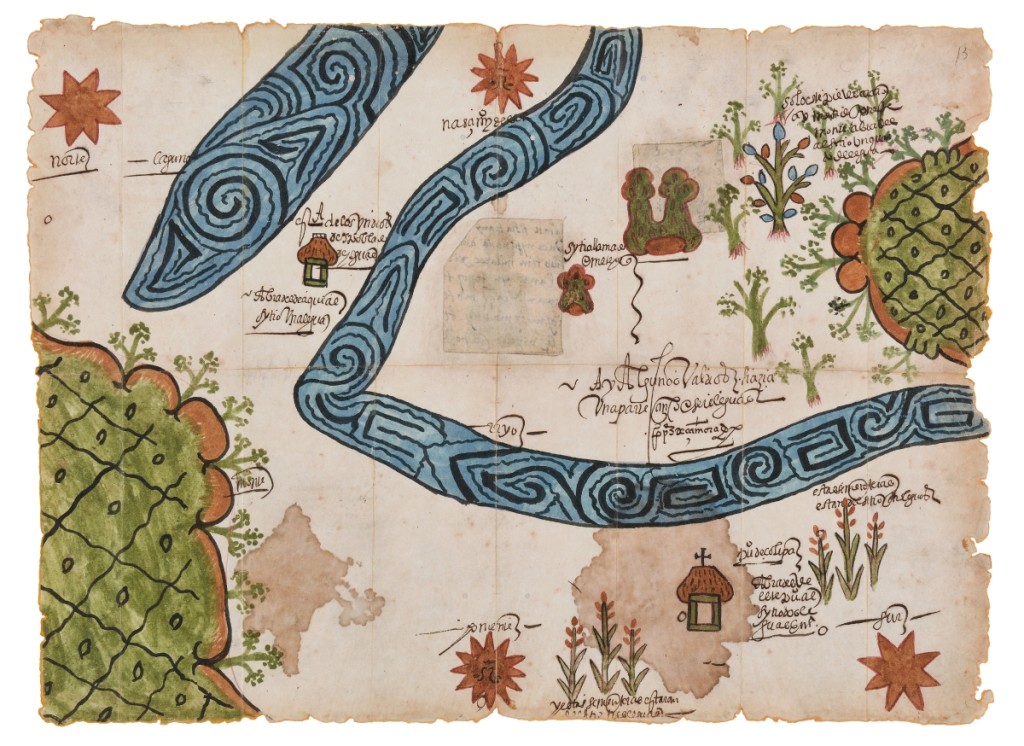

Perhaps the cornerstones of the exhibition, the facsimile maps of Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Indigenous “Mapas de Merced” – recreated by contemporary Mexico City artist Tlaoli Ramirez Téllez – show the sophistication of Indigenous resistance to “royal land grants, documenting the long-standing relationships that Indigenous communities had with their lands.” A facsimile of “Map of Zolipa Misantla, Veracruz, 1573,” for example, is a beautifully rendered assembly of landforms and landmarks, with a geometrically decorated serpentine river winding on and off the paper. And yet, for all its decorative and artistic power, one knows instinctively that this map is a useful tool, one that could easily move you around in this space.

Facsimile of “Map of Zolipa Misantla, Veracruz, 1573” originally by Corregidor Pedro Pérez de Zamora. Facsimile of the original in the collection of the Archivo General de la Nación by Tlaoli Ramírez Téllez, 2021. Mixed medium, acrylic, ink and watercolor on paper. Courtesy of the artist, commissioned by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. ©Tlaoli Ramírez Téllez.

“Mixpantli” brings to mind China Miéville’s astonishing fantasy-mystery novel, The City & The City, about two different cities, Beszel and Ul Qoma, that – inexplicably – occupy the same geographical and physical space. Moving between them is difficult and the residents of each city are taught to “unsee” the residents of the other. There are places where the membrane between the cities is thin and there are those who “Breach” the boundaries and are punished. One of those who police the invisible boundary says, “You cannot train yourself to successfully and sustainedly unsee and unhear. You do them all the time, but they also fail, repeatedly, and you cheat, repeatedly, in all sorts of small ways… It is absolutely about absolute fidelity to those particular urban protocols, exaggerations or extrapolations of the ones that I think are all around us all the time in the real world; but it’s also about cheating them, and failing them, and playing a little fast and loose, which I think is an inextricable part of such norms.”

This is the dynamic of colonizer and colonized, to fail to see, willfully. For the colonizer, the superimposition of one’s “superior” culture and way of life blurs the beauties of the existing culture. For the colonized, memories of the past and dreams of a new future help keep the violations of colonization in check and fuel the flames of resistance. But, as Miéville writes, for those on both sides, there are moments that cannot be unseen and palimpsest traces of maps upon other maps.

“Mixpantli: Contemporary Echoes,” for example, finds new ways to map familiar spaces. Sandy Rodriguez’s “Rainbows, Grizzlies, and Snakes, Oh My! – Conquest to Caging in Los Angeles” (2019), maps the history of Los Angeles, from missions to immigrant detention facilities, while “You will not be forgotten. Mapa for the children killed in custody of US Customs and Border Protection” (2019), locates the places where immigrant children died under the custody of US Customs and Border Protection. Lastly, “We Are Here,” produced by the women-led organization Comunidades Indígenas en Liderazgo, in partnership with the UCLA, is an interactive, digital map of the Indigenous communities of Los Angeles.

In his 2009 Guardian review of the exhibition “Moctezuma: Aztec Ruler,” at the British Museum, Jonathan Jones cites the obsidian mirror as perhaps the most telling object in the exhibition: “Your features swim in and out of view, like a vision in smoke… There is an occult quality to the image of yourself that materializes for a moment, making you wonder exactly who you are.” Identity and place become a “banner of clouds,” maps overlaying maps in a “Mixpantli” whose layers cannot be peeled away.

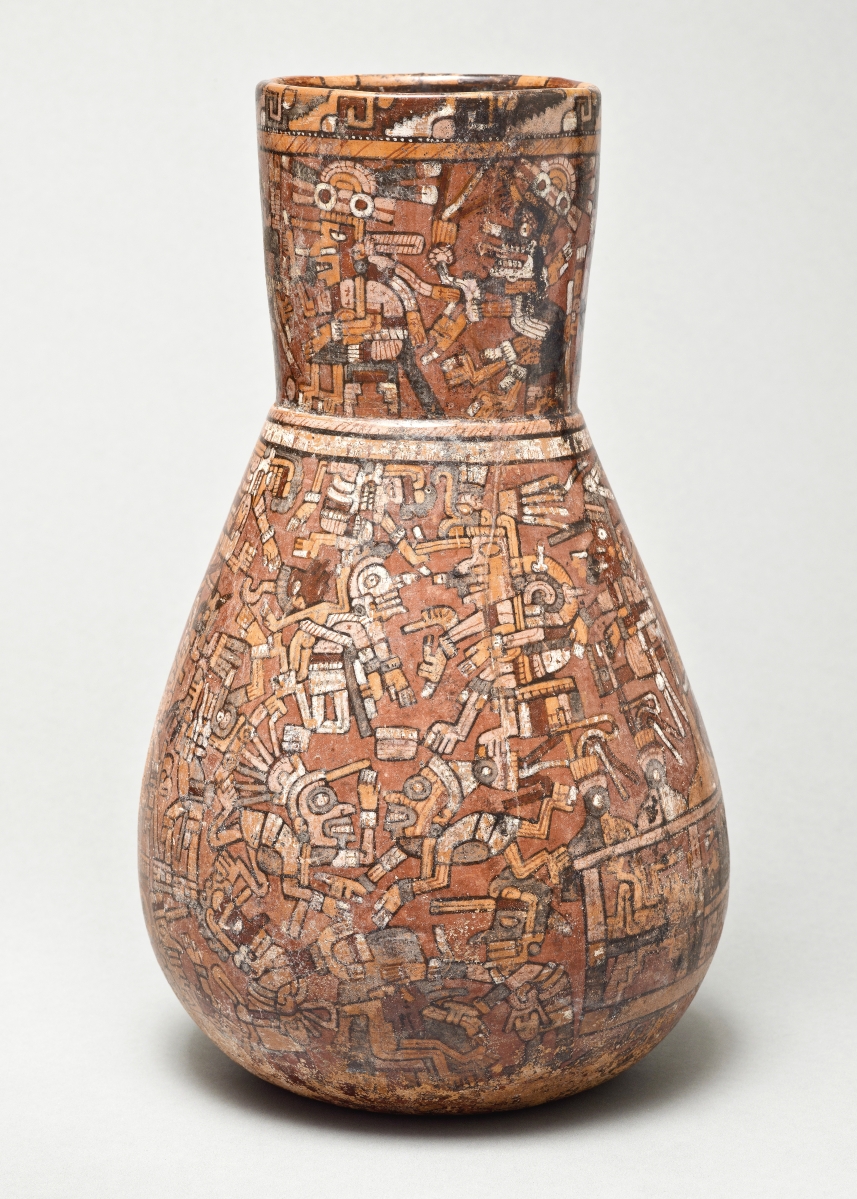

Vessel with Codex-Style Scene, Mexico, West Mexico, Nayarit, Mixtec-Puebla or International style, 1350-1500. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by Camilla Chandler Frost. Photo ©Museum Associates/LACMA.

Maps. Nowadays, Google Earth and Apple Maps plug us into satellites and off we go, whether it’s to the next neighborhood over or to the edge of the galaxy. Still, maps and the lines and names on them sometimes take on tremendous meanings in disparate claims from different peoples: Derry and Londonderry. Israel and Palestine. Istanbul and Constantinople. Taiwan and China Taipei.

Once upon a time, even family gatherings began with conversations about the routes guests took to get there, about shortcuts, hazards and mileage. Wrong turns turned into tales that led to mental notes to, say, stay off Wisconsin Highway 22 between Plainfield and Weyauwega if there’s even a hint of a snow squall in the air. There be dragons. But we don’t think much about maps anymore, not as we once did. Even where I live, the tension over maps and the names on them is palpable. What was once the Tappan Zee Bridge is now the Governor Mario Cuomo Bridge. However you feel about it – and feelings run hot here – displacing “Tappan” essentially eliminates the name of one of the Lenape people who inhabited the Hudson Highlands, while erasing “Zee” – the Dutch word for sea – distances us from the original Europeans who settled here and how they saw the Hudson River (Muhheakantuck, or “river that flows two ways” in Lenape) and its inhabitants. Similarly, the town just north of me was, for many years, simply known as North Tarrytown. In 1996, in a bid to recognize the possibilities of the place as a tourist destination, North Tarrytown reverted to its original name – Sleepy Hollow – as in “The Legend of…,” Headless Horseman and all. Yet, to this day, bumper stickers here read, “North Tarrytown Forever.” Names attach to places. People attach to both. In truth, resist though we may, perhaps we are all “banners of clouds.”

LACMA is at 5905 Wilshire Boulevard. For information, www.lacma.org or 323-857-6000.