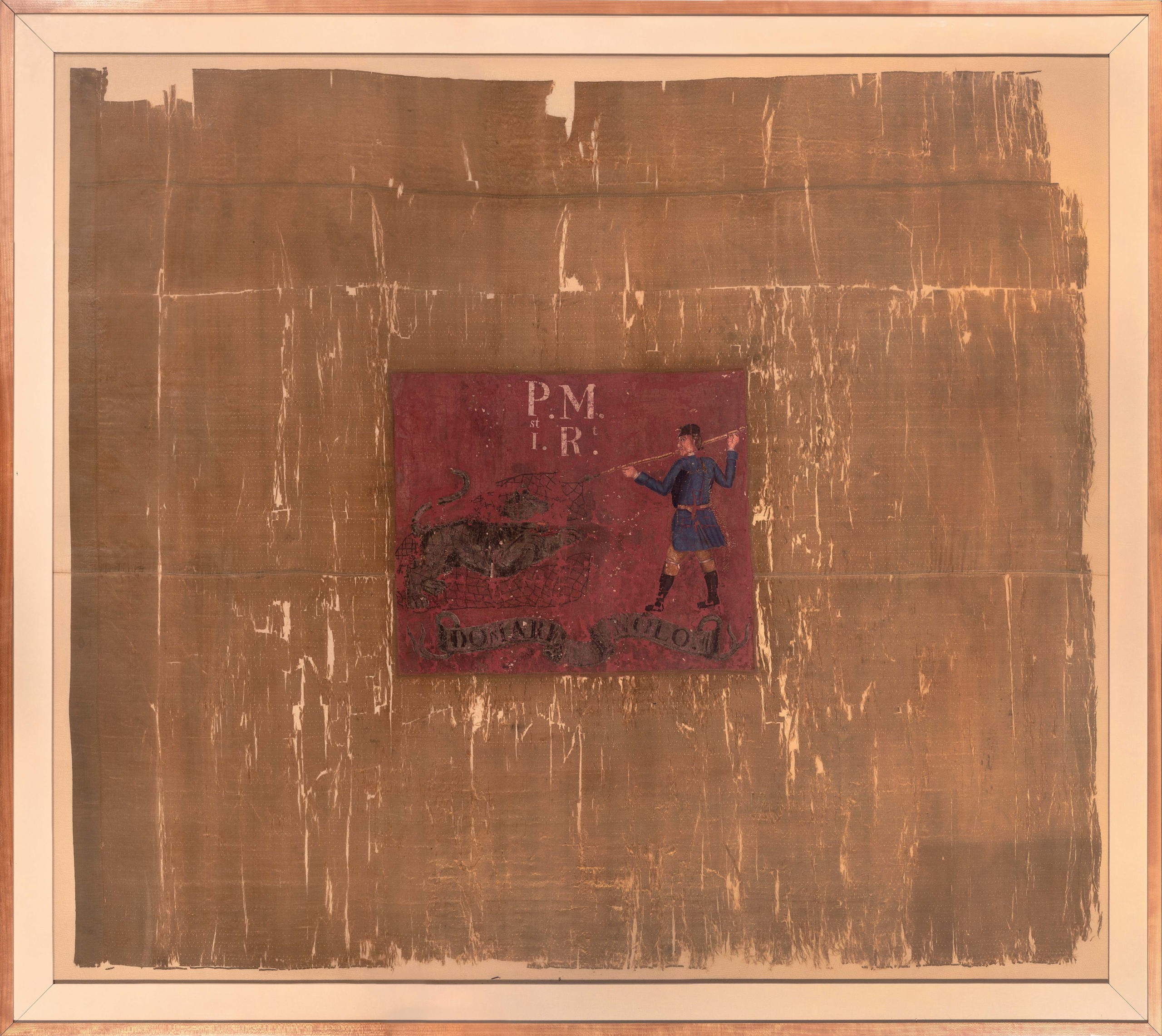

Light Horse of the City of Philadelphia flag, on loan from the Museum of the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry.

By Andrea Valluzzo

PHILADELPHIA — Flags tell all kinds of stories, from the colors and materials flag makers chose to the symbols, painted decoration and mottos used. The 30-some American flags from the Revolutionary War era that survive today — out of the hundreds made and carried by soldiers fighting for the American cause — tell stories of how a fledgling nation was trying to create its national identity and espouse its political ideology.

The Flag Act of June 14, 1777, passed by the Second Continental Congress, proclaimed that “the flag of the 13 United States be 13 stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be 13 stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.” Before that act standardized American flags, the ones carried onto the battlefields by troops and militia units were quite varied in design.

In a kickoff to the nation’s Semiquincentennial, which will be celebrated in the summer of 2026, the Museum of the American Revolution has pulled off a Herculean feat in gathering together more than half of the surviving Revolutionary War American flags into an exhibition two years in the making. “Banners of Liberty: An Exhibition of Original Revolutionary War Flags” opened April 19 and is on view through August 10. The opening date was chosen deliberately, precisely 250 years after the “shot heard round the world” at the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

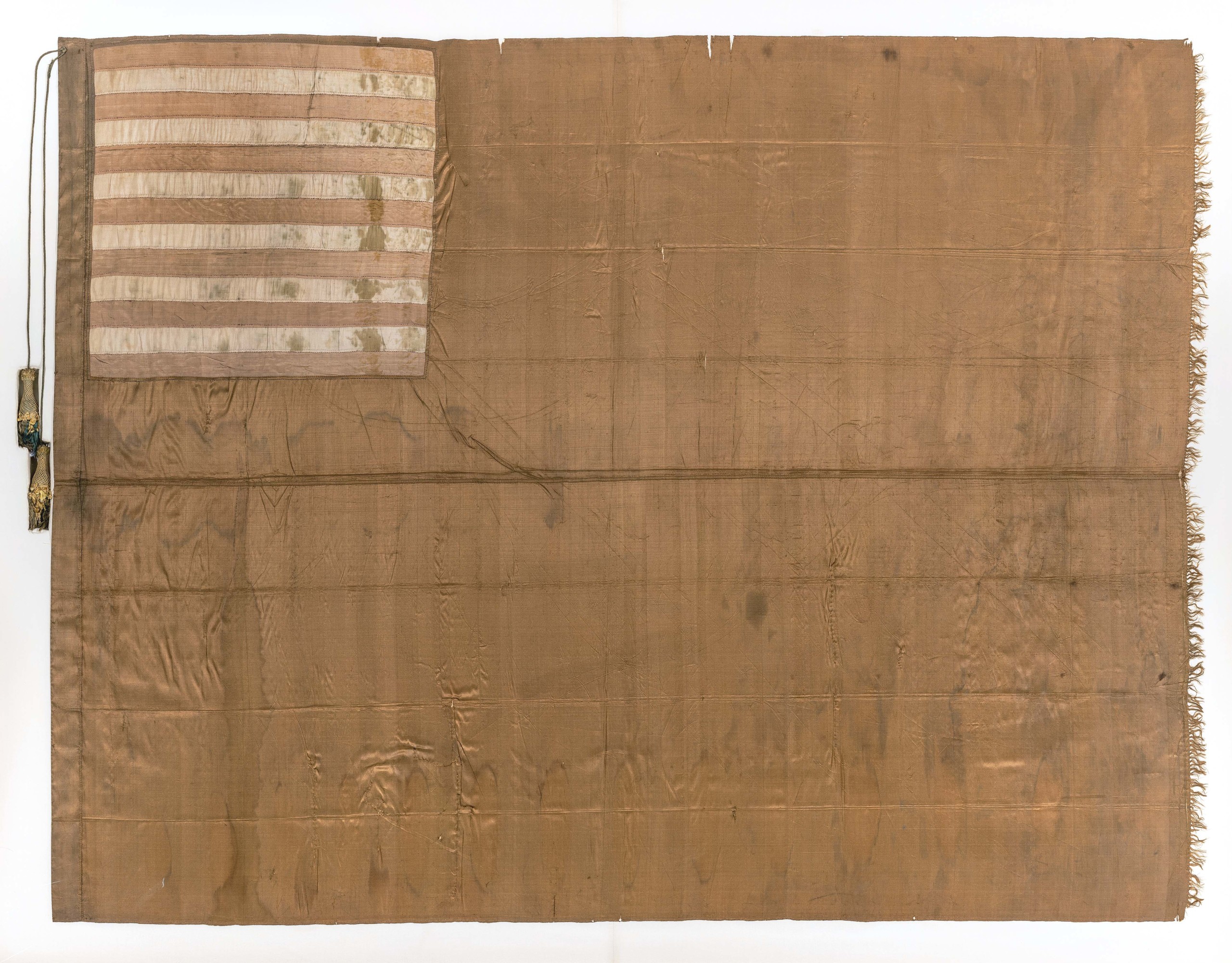

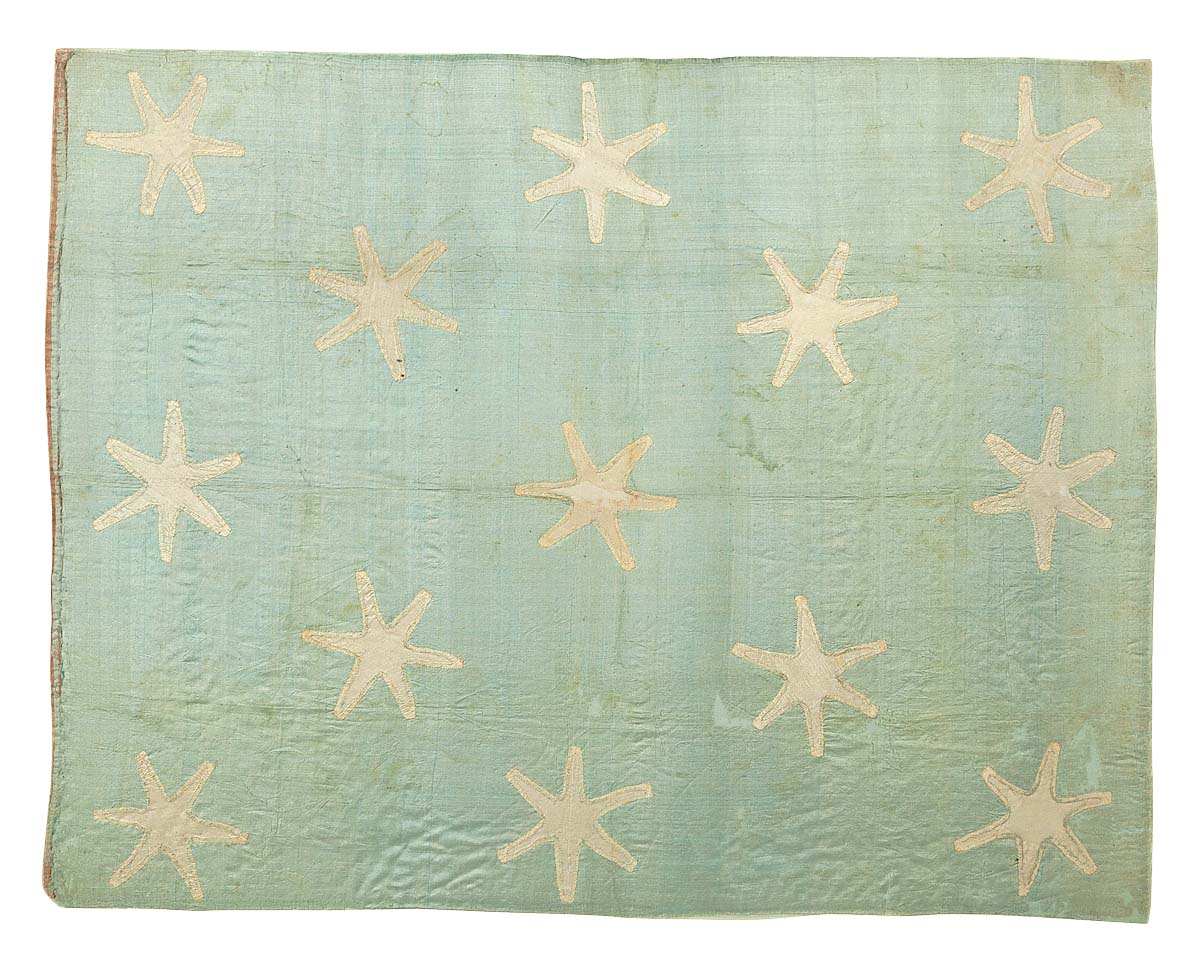

A 13-star flag of the United States of America, Eighteenth Century, on loan from Jeff R. Bridgman American Antiques, Inc.

This display, featuring 17 rare and historic banners, promises to be a “showstopper,” according to associate curator James Taub, and the largest gathering of such flags since the end of the revolution. Some flags are returning to the very city they were made for the first time. Six also secured grant funding to undergo conservation projects before the exhibition to preserve them for this presentation and so future generations can study and appreciate them.

Among the flags that underwent conservation was a pair made for the Second New Hampshire Regiment, which are two of the largest flags in the exhibition, measuring 68 by 61 inches and 65 by 60 inches. On loan from the New Hampshire Historical Society, which acquired them in the early Twentieth Century, the flags were made by Fanny Johonnot Williams and painted by Daniel Rea, Jr. They were captured by the British during the Saratoga campaign of 1777.

“These flags are really incredible survivors because of the symbolism on both of them,” senior curator Matthew Skic said. One flag is known as the Chain of States flag as it has in the center a radiating golden sun with the motto, “We Are One,” surrounded by a circle of interlinked gold rings with each of the names of the country’s first 13 states. “This was a device created by Benjamin Franklin and first appeared on currency for the United States and made its way onto this flag,” Skic said. Its companion flag has a blue silk field with the motto, “The Glory, Not the Prey,” above a pictorial shield containing the regiment’s name.

Second New Hampshire Regiment flag (Chain of States), New Hampshire Historical Society, gift of Edward Tuck; conserved with support from the Artist Preservation Group.

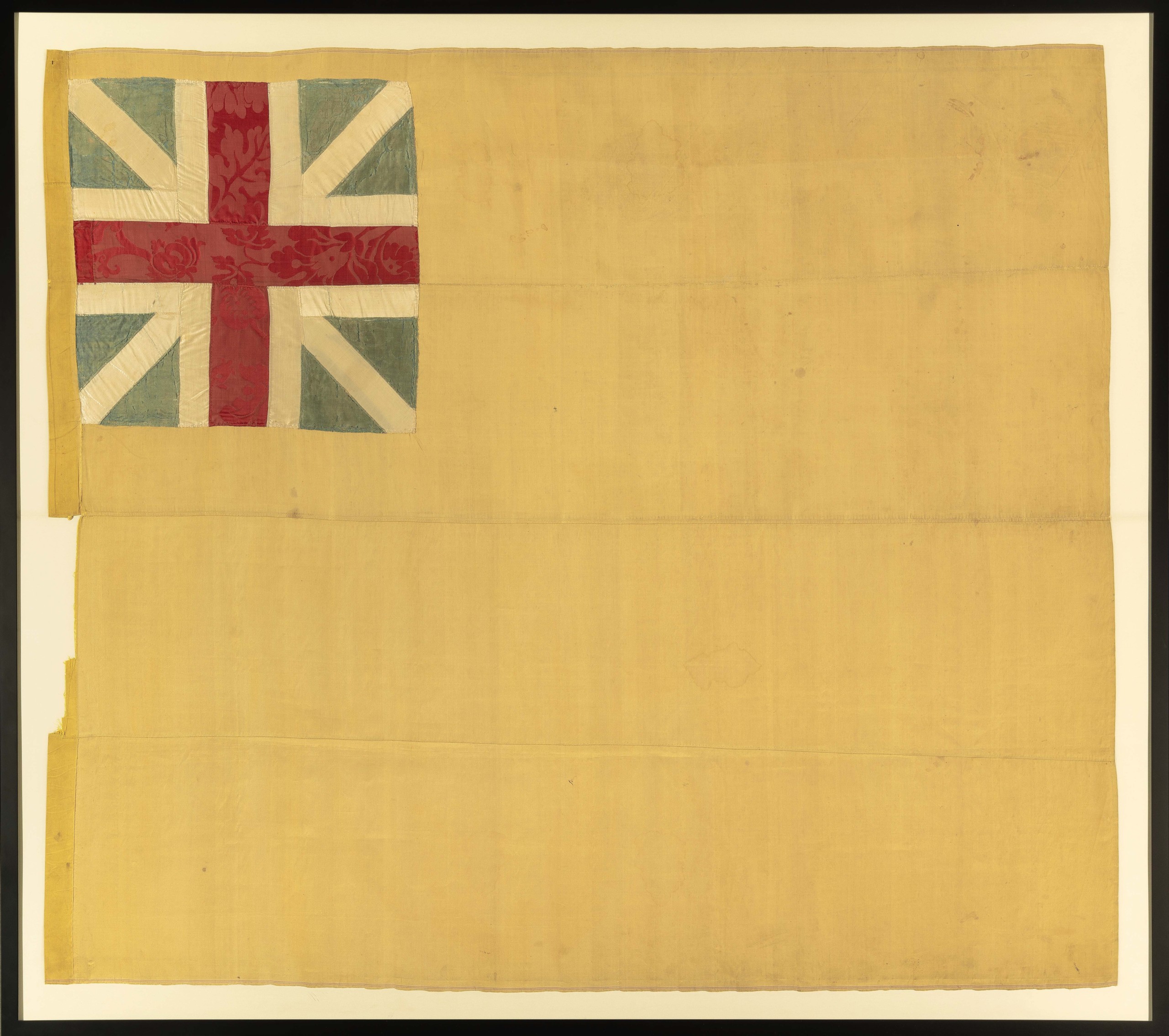

Worth noting is that in many flags, the rectangular emblem known as a canton is typically placed in the upper left corner. With the aforementioned two, the canton is at the upper right, indicating how they were to be displayed. The cantons are also notable for being made while the new nation still had ties to Great Britain so both cantons denote the British Union with the crosses of St Andrew and St George.

Such British symbolism soon fell out of vogue. A fine example is a First Pennsylvania Battalion flag, featuring 13 arrows tied in a bundle in the center field, with the motto “United We Stand.” However, the canton there now is not the original. When the flag was first made, it had British crosses that were likely removed just after the Declaration of Independence was signed and replaced with stripes.

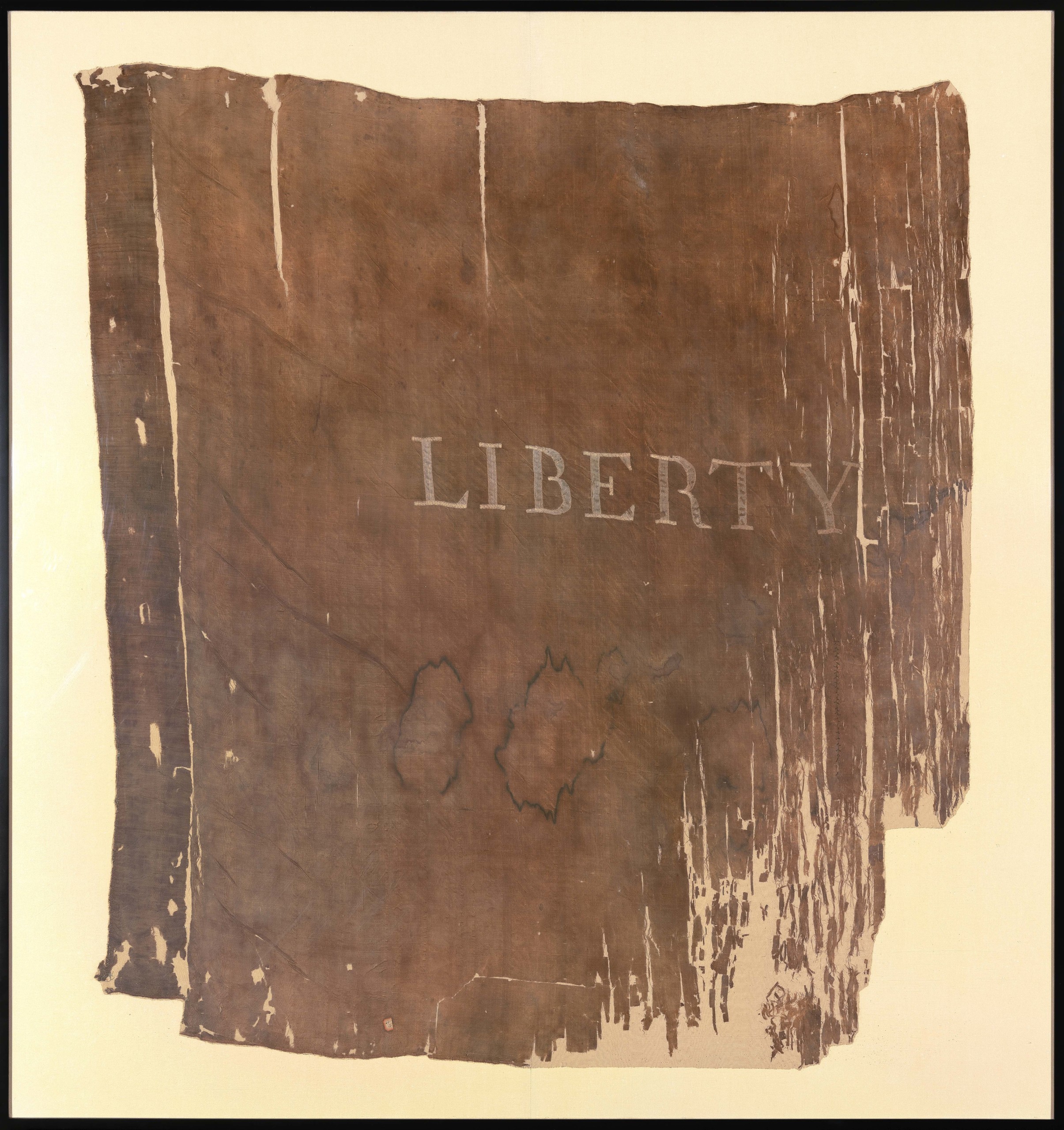

Not surprisingly, given the extensive destruction in the South during the Civil War, most surviving flags originated north of the Potomac River. A notable exception hails from the backcountry of South Carolina — the Second Spartan Regiment of Militia. Colonel Thomas Brandon served in that unit and brought the flag home after the war, storing it in a small box. It was passed down through his lineage and the box has all of its succeeding owners’ names inscribed on the lid interior. The flag and box are both on display in the museum.

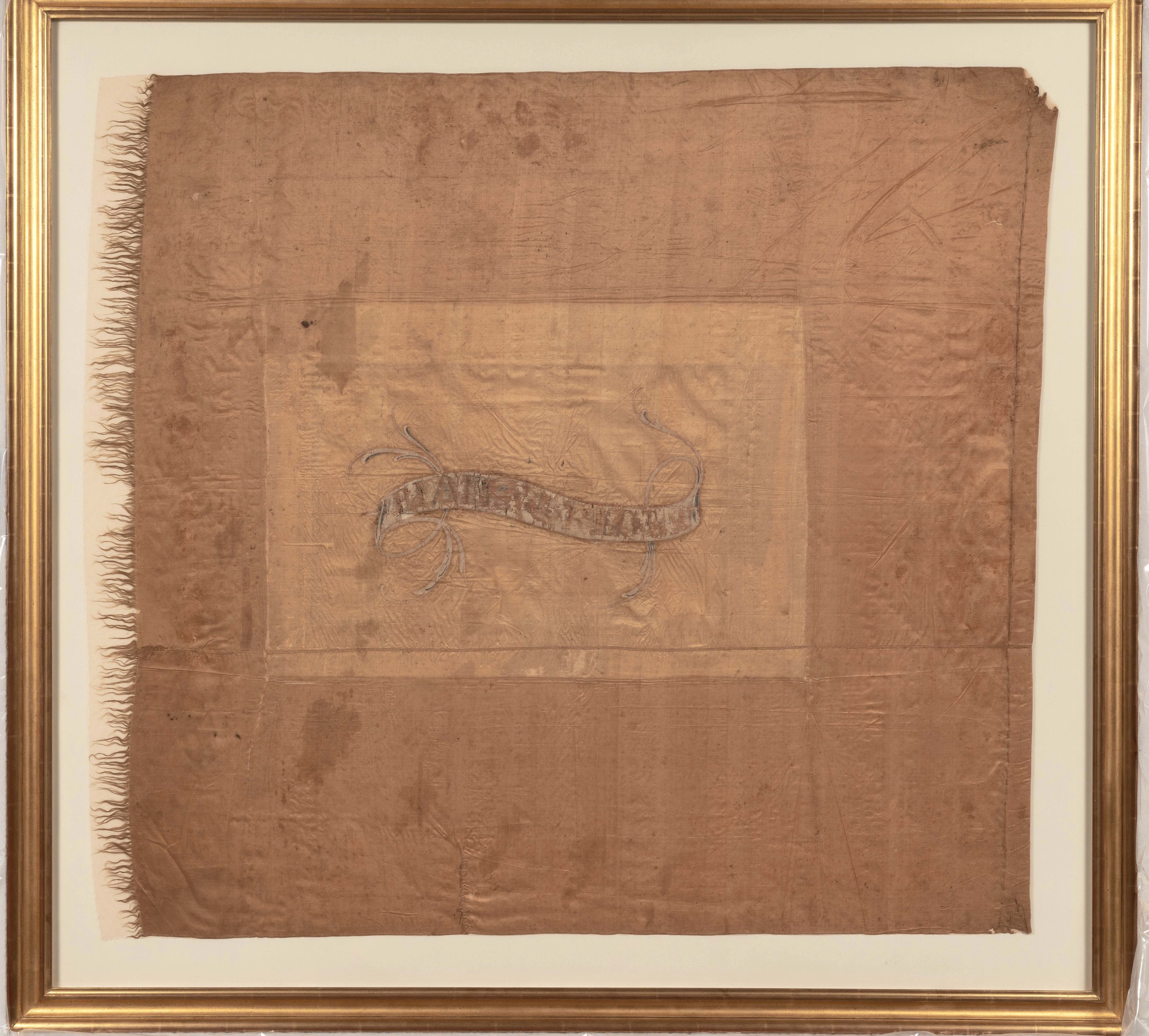

Second Spartan Regiment of Militia flag, on loan from the Friends of the Spartanburg County (S.C.) Library, Inc.

On the back, the flag has seven horizontal stripes painted in gold paint. The six blue “stripes” in between the gold ones make a total of 13, a prominent number used on these early flags well before the “Stars and Stripes,” with 13 stars and 13 stripes, became standard. In the center of the flag’s indigo blue field is a depiction of a “Spartan” dog and a snake, whose exact meaning historians continue to guess at. “Does that dog represent South Carolina or Britain, or does the snake?” Skic pondered. “We know from other artwork and one other flag that survives from the war that the rattlesnake became associated with symbolizing the United States in the fight against Britain as an animal that sounds a warning before it attacks.” The dog could also be a Shakespearean reference, he said, noting that Othello has a line comparing the villain Iago to a bloodthirsty Spartan dog from ancient Greece.

One of the exhibition’s sponsors is longtime antique American flags dealer Jeff Bridgman, who has studied or appraised many of these flags. On loan from his collection is a flag that technically post-dates the Revolutionary War but is quite possibly the earliest surviving example of a 13-star American flag known. It is the final flag in the exhibition and clearly shows the evolution of the American flag’s design. “Thirteen star flags have been made throughout our history in America [since the Flag Act], but almost none exist from the Eighteenth Century,” Bridgman said. Coming out of the Mastai collection, this flag is unusual in that it features vertical stripes, instead of horizontal. Another important design technique is that placement of the 13 stars in the canton forms a larger star, known as a “Great Star” pattern.

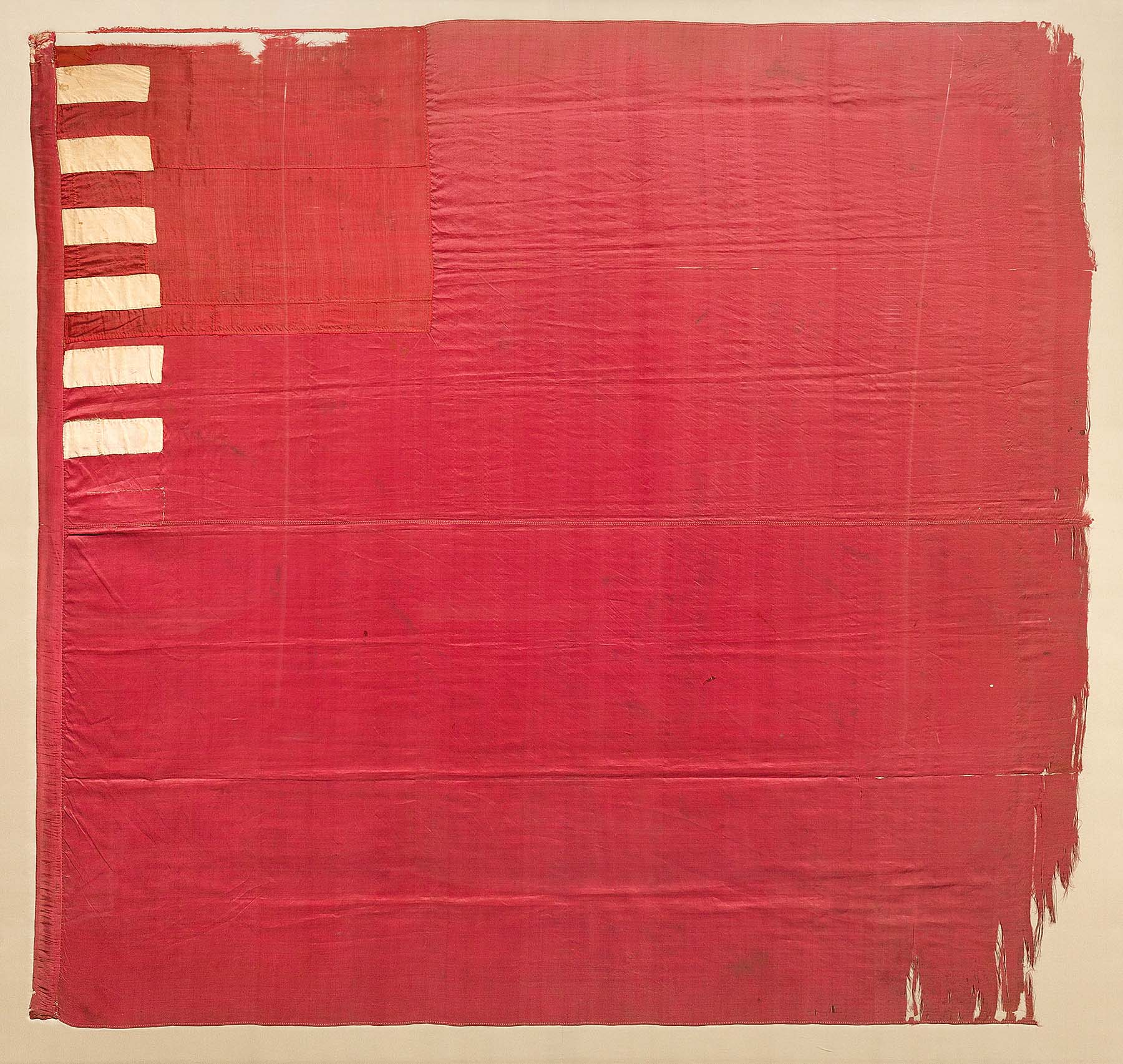

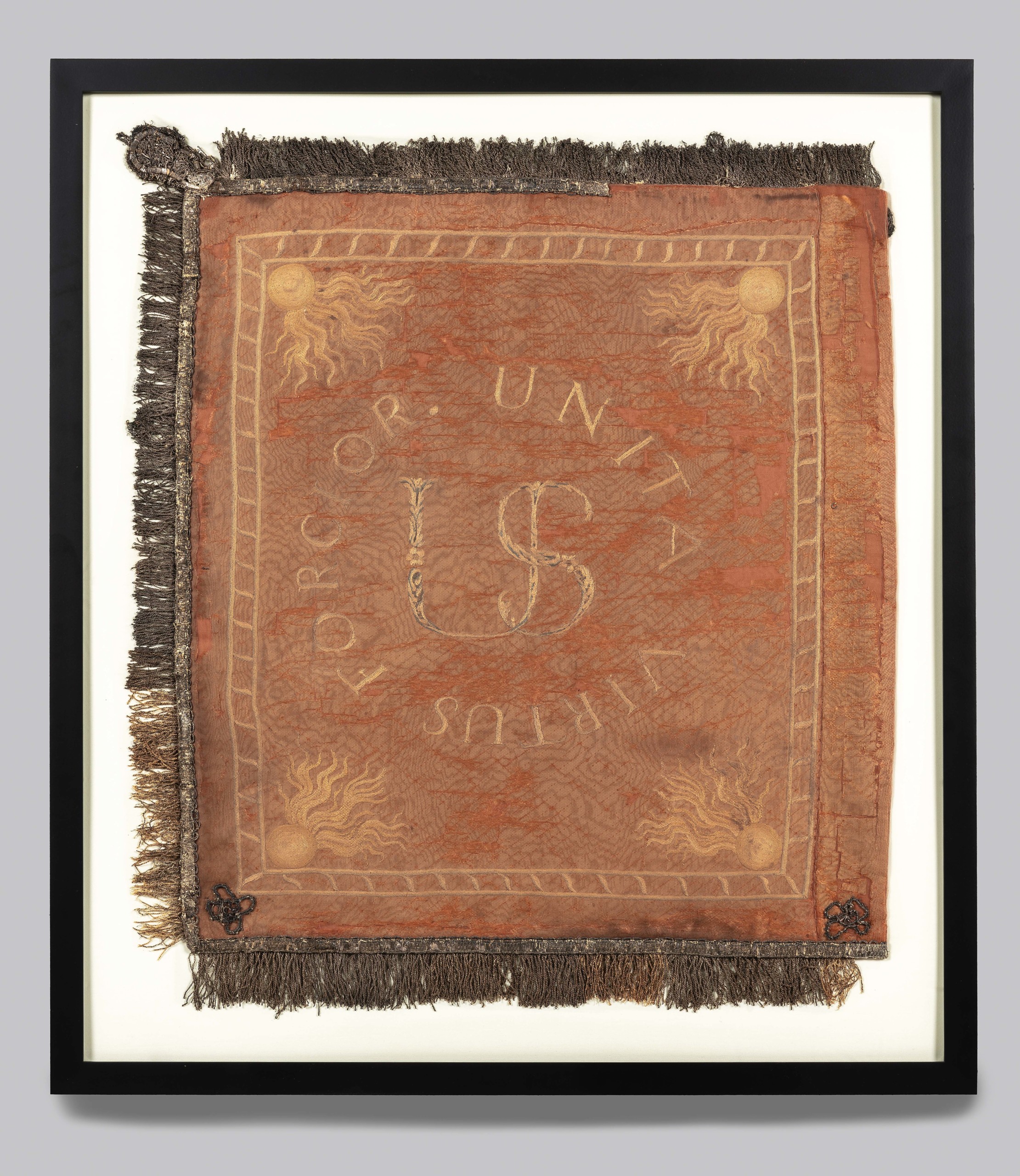

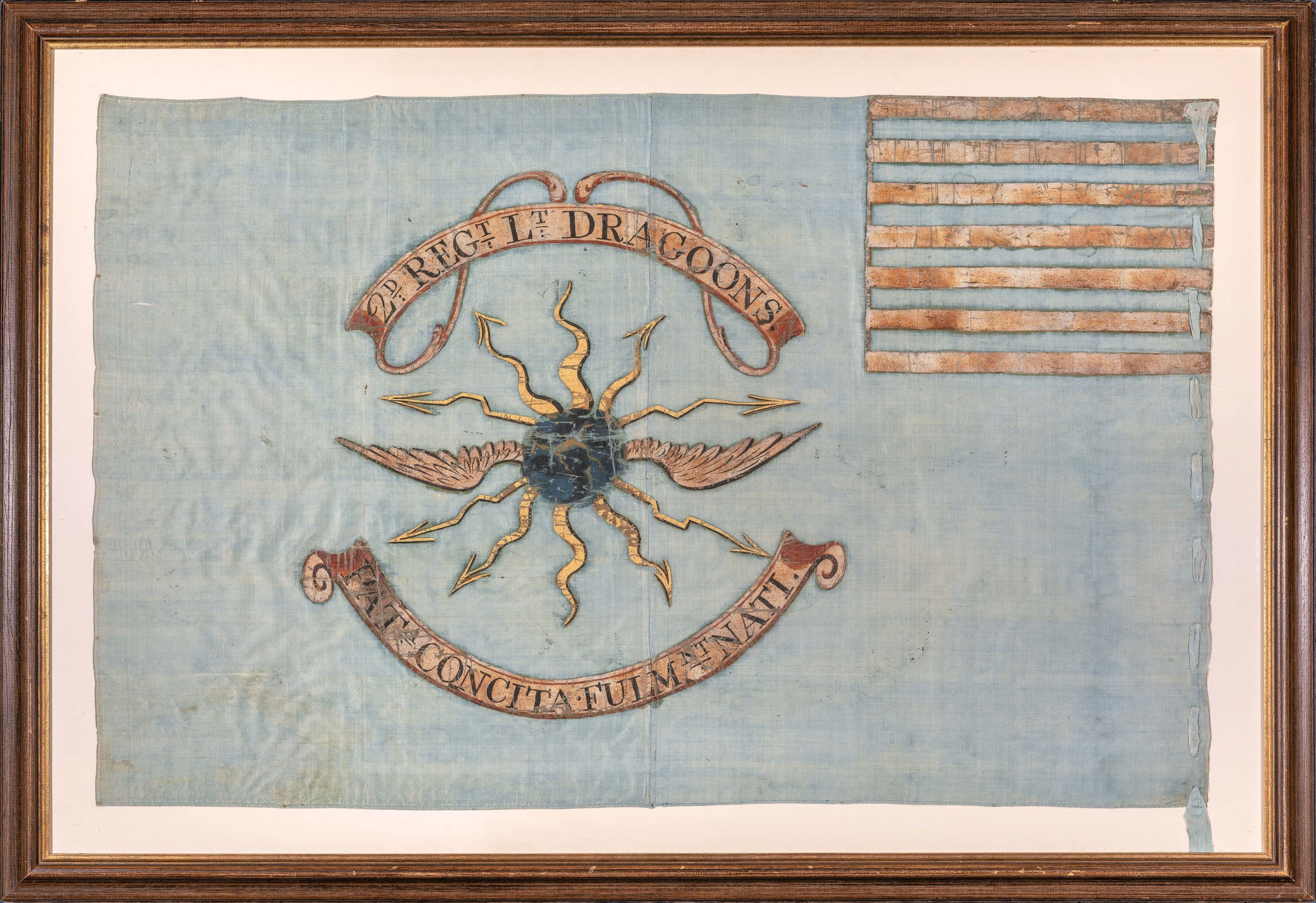

Second Regiment of Light Dragoons standard, Museum of Connecticut History, Connecticut State Library, Hartford, Conn.

Bridgman has seen most of the exhibition’s flags before, individually, but is excited to see them all together in one room. “There are a couple important ones I have never seen,” he said. “I wish they could have gotten more, but to get this many was a Herculean feat. There may never be anything like it again.”

The flags here are both small and large. Making a big impression is a small cavalry standard from the Second Regiment of Light Dragoons, on loan from the Connecticut Historical Society. Standards would have been stationary and used to mark the position of an important person or unit. Taub explained the flag’s field depicts a globe with lightning bolts emanating from it and Latin text that roughly translates to “Her Sons Will Answer With Thunder.” “People were very interested in Greek and Roman mythology at this time, so it’s very Classical in its reference,” he said.

A flag for the Light Horse of the City of Philadelphia incorporates Americanist symbols from the city and the state of Pennsylvania, depicting agriculture and commerce. A female figure likely represents Liberty or Victory. Confirming these are the very ideals the country was working to attain, the flag’s crest reads: “For These We Strive.”

George Washington’s commander in chief’s standard, Museum of the American Revolution, conserved with funds provided by the Pennsylvania Society of Sons of the Revolution and its Color Guard.

An exhibition highlight is the pride and joy of the museum — General George Washington’s standard as commander in chief. Only displayed at the museum once before since its opening on April 19, 2017, it was used in the war to mark Washington’s headquarters and location on the battlefield. Given its fragility, the flag has been resting in the dark for several years so that it can safely be displayed during the full run of the exhibition.

“Banners of Liberty” surveys an important chapter of American history, bringing together key artifacts designed as military tools that became inspirational works of art. “You could say we’re creating our own history because there are some new pairings of flags that never saw each other in the Revolution but are now in the same space for the first time,” Taub said.

The Museum of the American Revolution is at 101 South Third Street. For information, 215-253-6731 or www.amrevmuseum.org.