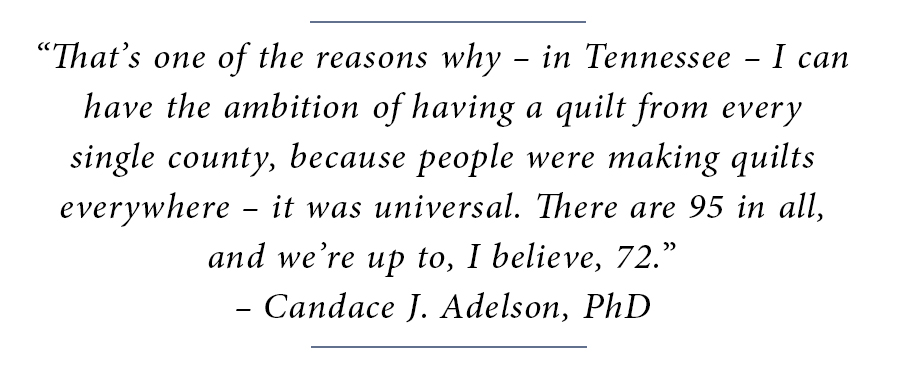

This Crazy Quilt of embroidered silks and velvets with three-dimensional dolls was made in 1883 by Amy Terrass Johnson Cowden (1861–1939) of Nashville in Davidson County.

By Karla Klein Albertson

NASHVILLE, TENN. – Quilts are a warm embrace on a cold night, a building block of the new family home. At times, they could be so much more – the primary outlet for a soul’s artistic creativity, even a fabric map to the structure of the universe. Nashville in recent years has become “hot,” that is, an attractive tourist destination for musical nights and food on the table fresh from the farm. This spring, “Between the Layers: Art and Story in Tennessee Quilts” – on view through July 7 – presents a focused offering of history, craftsmanship and design at the newly constructed Tennessee State Museum which opened on the city’s Bicentennial Capitol Mall last October.

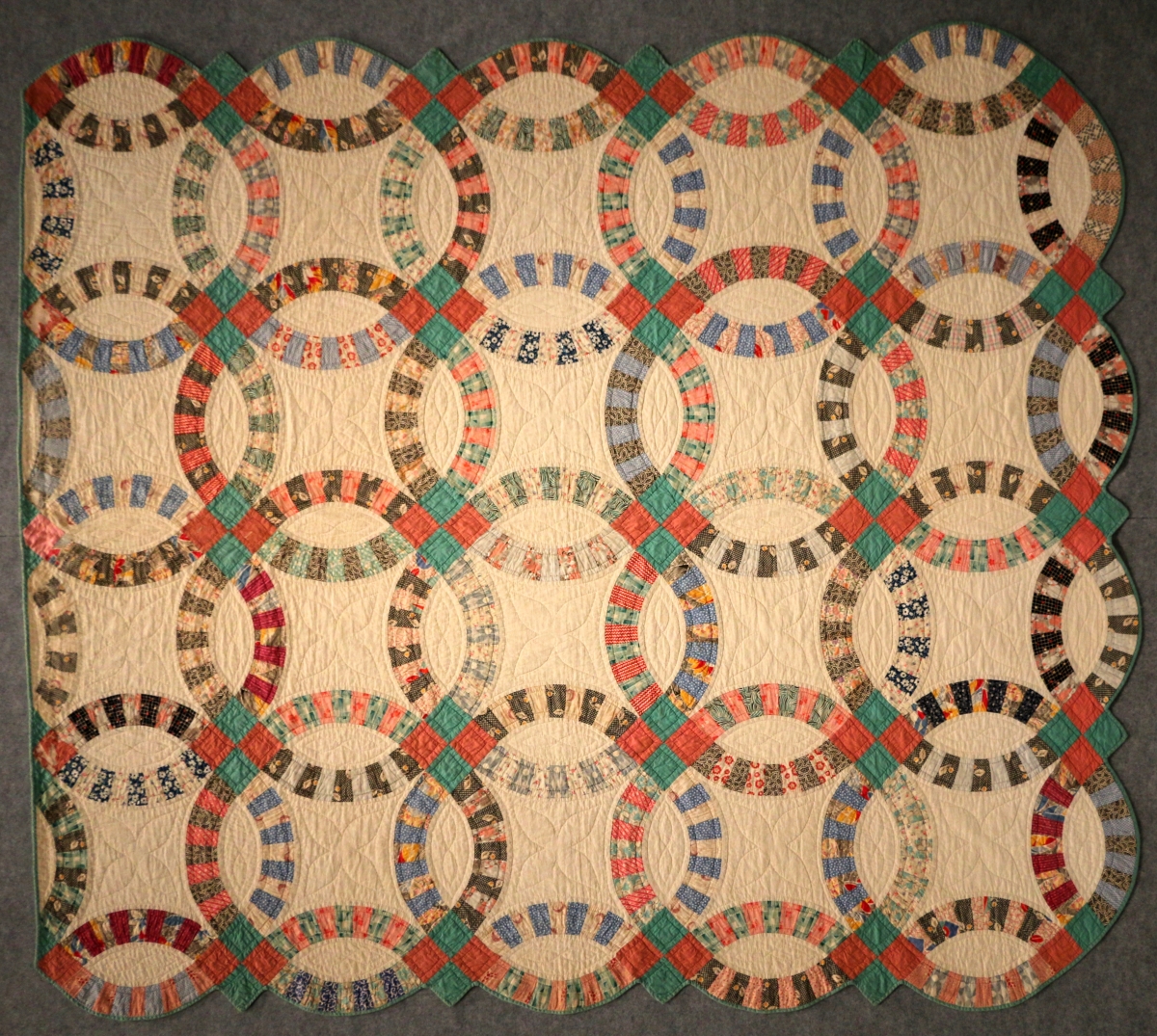

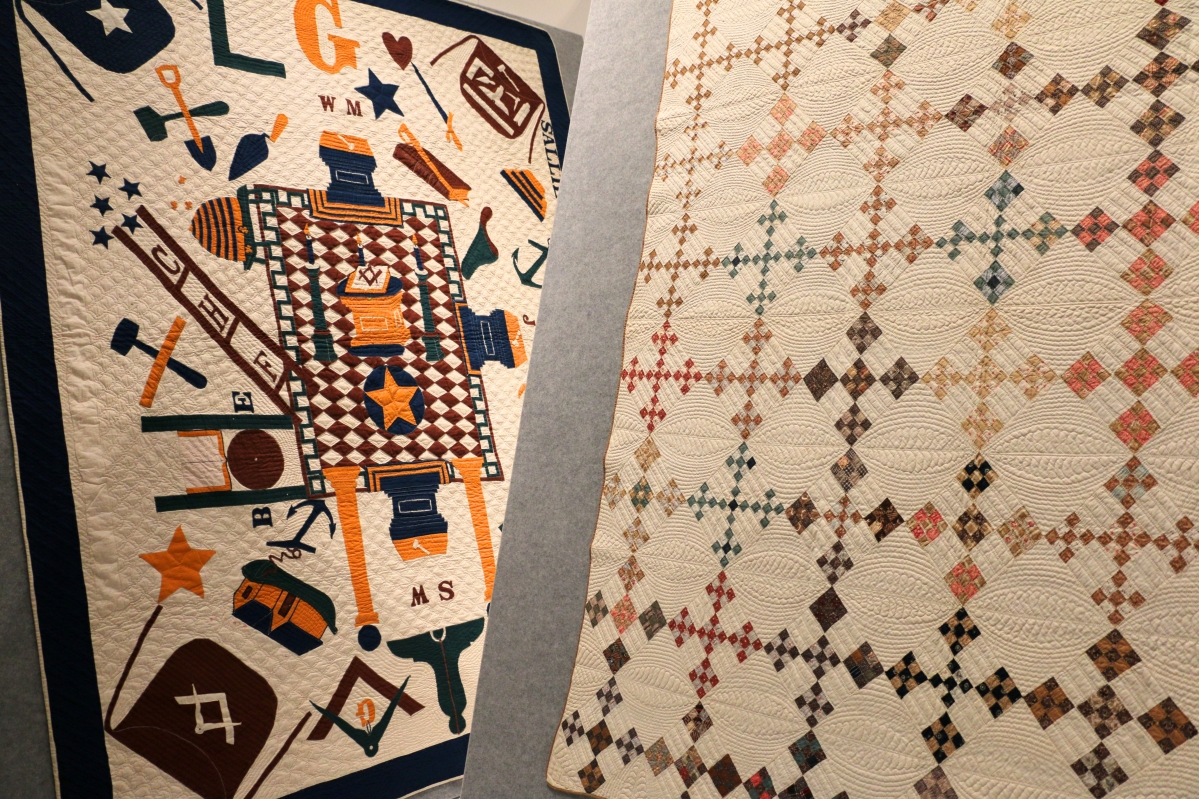

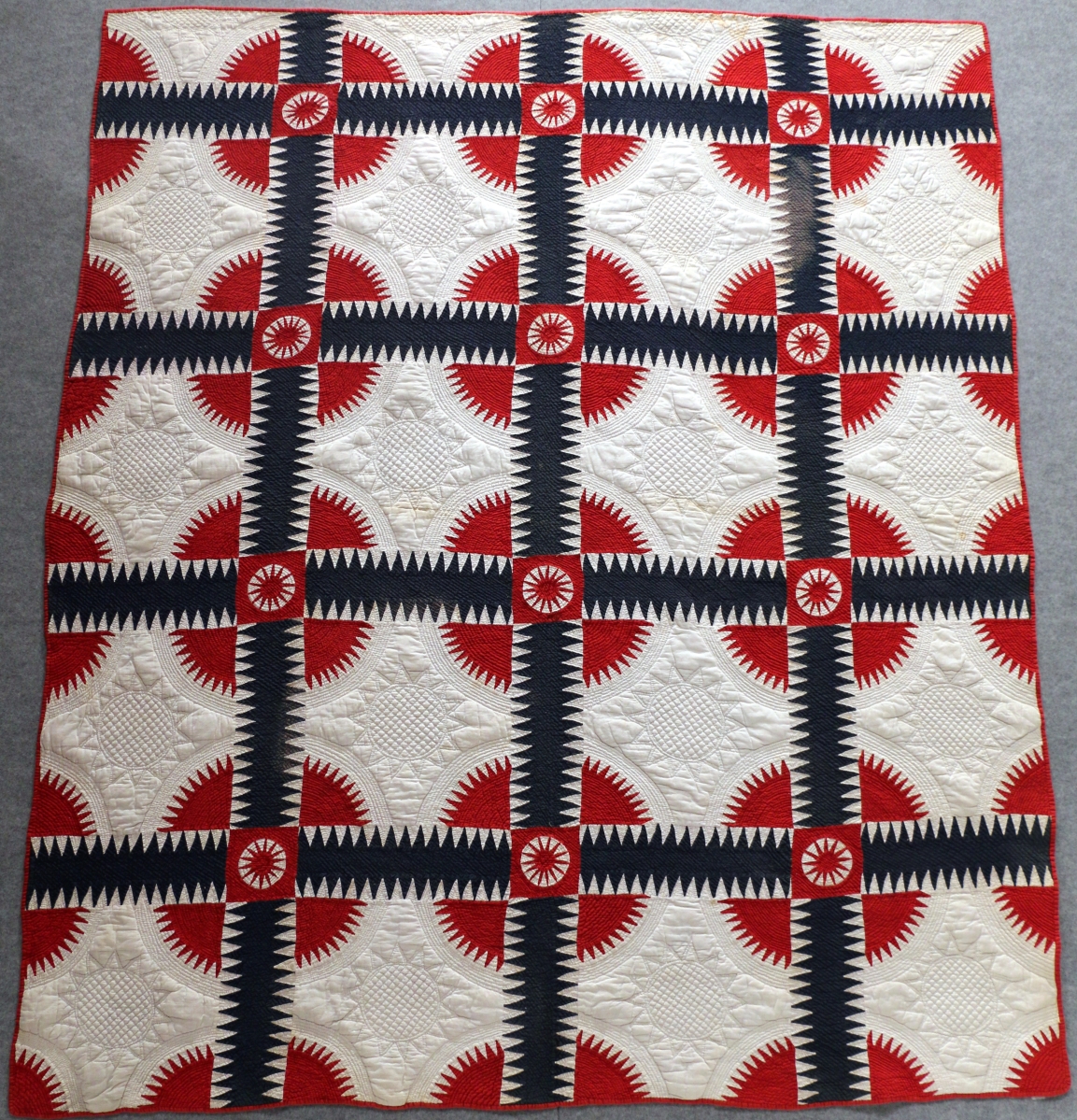

The quilts, which range in date from the early Nineteenth Century to modern works, have all been selected from the institution’s deep permanent collection of documented examples. The remarkable variety of styles and variations reflects the long, narrow state’s natural divisions across its 440-mile span. Older, more sophisticated examples often come from mountainous East Tennessee on the Virginia border; large urban centers with networking opportunities sprang up in Middle Tennessee; and West Tennessee was more influenced by goods and fashions moving up the Mississippi River from larger cities in the South.

Candace J. Adelson, PhD, senior curator of fashion and textiles, organized the exhibition and talked with Antiques and The Arts Weekly about its goals during a recent tour of the galleries: “I wanted to do a historical study of quilts in an academic way. There have been many studies of other decorative arts in the past. Quilts were kind of a latecomer to that type of examination. About 1979-80, the first state quilt surveys happened, and people like Bets Ramsey and Merikay Waldvogel were beginning to be interested in the details of the history – who made each quilt, when, why and how does it differ in style from quilts made earlier or later. Was it made by poor people or wealthy people?”

“Unless it uses expensive fabrics, such as silks, you often can’t tell whether the person was wealthy or not. Quilts are really levelers across society, gender and race in this country and certainly in Tennessee. They were necessary and the easiest way to keep warm, even if you didn’t have a lot of money. You could put a collection of scraps together, sometimes the makers reused the batting from an older quilt because they didn’t have money for new batting. Quilts were in use all over the state, and they have been for over 200 years. That’s one of the reasons why – in Tennessee – I can have the ambition of having a quilt from every single county, because people were making quilts everywhere – it was universal. The goal is to have a quilt from every single county; there are 95 in all and we’re up to, I believe, 72.”

The curator continued, “I had a very ambitious teaching goal here. We present visual material, historical material and technical material. I wanted to draw people who had never really been interested in quilts, never had looked at them, even though they may have used them. I wanted to have an exhibition where that person would be caught up by the beauty of these quilts and become interested in their history and design. I wanted to do it through the design, and that’s why I grouped the quilts in different design types, such as flowers. The flowers are a theme, and the patterns are what we call a ‘block’ in quilting, a unit of design that you put together in different ways to create different effects. The plan was not only educating visitors about quilts in particular but getting their eyes looking at the difference between one object and another, which is really blatant in the quilt. You can have a star in green and a star next to it in red, and they look totally different, even though it’s exactly the same design.”

As Adelson mentioned above, the regional quilting tradition had been explored previously in an exhibition which toured state institutions from late 1986 to early 1988. Inspired by the earlier Kentucky Quilt Project, organizers Bets Ramsey and Merikay Waldvogel produced an accompanying volume, The Quilts of Tennessee: Images of Domestic Life Prior to 1930. That excellent reference is still available through online vendors and includes several quilts which appear again in the current show, such as an 1883 crazy quilt with three-dimensional dolls. These same authors were in Nashville recently to take part in a conversation on the new exhibition, and a Wondrous Star pattern wall hanging stitched by Ramsey in the 1970s is on view in the design section of the show.

As the subtitle suggested, that earlier catalog emphasized personal stories connected to the makers of the individual textiles. For example, a colorful wool Dresden Plate pattern quilt, circa 1890, was accompanied by a photo of its maker, Martha Elizabeth Brooks Randolph. She is shown in her later years “working out” in a Middle Tennessee field by hefting two large milk cans. The rather harrowing entry reads, “She was a brave woman who at twenty-one years of age married a widower with 11 children, and they had four more of their own. She made all their clothes, socks, quilts and blankets and attended to chores of a farm.” Such histories stand as a reminder that, although quilts may be bright and that overused word “graphic,” they were absolute household necessities when December winds blew through a drafty house and embodied weeks of work by a talented seamstress who juggled many duties.

“Between the Layers” is an opportunity to tell further tales of quilts and their creators’ lives. The oldest dated quilt in the current exhibition, featuring a central Eagle in blue on a white background, recalls the earliest years of statehood in Tennessee. Rebecah Foster made the signed quilt on which she embroidered “October 5, 1808.” Not one of the original 13 colonies, Tennessee became the 16th state in the Union on June 1, 1796, only 12 years before Foster stitched her quilt at Nashville in Davidson County.

As a description of this quilt explains, “While little may be known about its creator’s life, the quilt she crafted reveals plenty about her, and the time and environment in which she lived. Foster signed and dated her striking work – the earliest known written date on a Tennessee quilt. The decoration expresses enthusiastic loyalty during a time when US relations with England were strained working up to the War of 1812. The central eagle is a common element in early 1800s decoration. Part of the United States Coat of Arms, it has been updated here to feature 17 stars for the number of states in 1808, instead of the usual 13. Around the eagle are oval frames finely embroidered with the names of the states. Each encloses a patriotic verse.”

A section of one verse reads:

“May God o’er fair Columbia reign and crown her counsels with success with peace and joy her Eagle bless And all her sacred rights maintain.”

The explanation continues, “Producing the quilt was an opportunity for Foster not only to show fervor for her country, but also to express her creativity and show off many talents expected of an educated Tennessee frontier woman – among them needle skills, spinning and weaving. She follows design fashions of her time, and enhances her quilt with virtuoso appliqué, embroidery and complex quilting. Although the blue printed fabric would have been an imported purchase, the white linen appears to be handspun and handwoven, possibly by Foster herself. Considering that it was made more than two centuries ago, the Eagle Quilt has survived in amazingly good condition, indicating that it was used very little and treasured by generations for both its message and its remarkable artistry.”

Two versions of a Log Cabin pattern quilt are displayed side by side. On the bed, a Barn Raising variation made in the 1920s in Rutherford County. Cotton with cotton batting; hand pieced. On the wall, a late-Twentieth Century Star variation by Charles Goddard (1927–2012) made in Memphis, Shelby County. Cotton with polyester batting; hand pieced.

Anyone who has ever touched a needle will be impressed by the challenging Sunburst variation quilt that was an all-hands-on-deck project of the Nunnelee family, who lived in Maury and Hickman counties in the mid-Nineteenth Century. The textile is labeled “A Surveyor’s Design” because that was the profession of father James “Marcus” de La Fayette Nunnelee (1826-1876) who may have used his instruments to lay out the complex design of undulating rather than straight arms, which was then executed by his wife Lucy Jane Nunnelee and their three eldest children. Exhibition labels carefully note the stitching scale of each example. This cotton Sunburst has an admirable seven stitches per inch, others as much as ten or 12 per inch. As anyone who had tried to repair a family quilt learns, it is extremely difficult to replicate this level of workmanship.

Displayed on a spool bed is a superb example of a later Nineteenth Century Crazy Quilt of pieced silks and velvets, which has been further ornamented with embroidery. The elaborate design was stitched by Amy Terrass Johnson Cowden (1861-1939) of Davidson County, who found the time for needlework in 1883, the year her daughter Eleonora was born in Nashville. Candace Adelson pointed out, “The crazy quilts were not made for use; they usually have no batting in them, so they were not meant to keep you warm. Most of them are not big enough for a bed, but they were a way for a woman to show off their needle skills, especially embroidery – they were show pieces. They weren’t meant to be hung, but they could be put on a piano or the back of a sofa.” This particular example is studded with 16 three-dimensional doll figures, and the label suggests that the maker may have been influenced by designs on Japanese pottery.

As Adelson outlined, quilts in the exhibition are grouped by design types, with varying versions displayed on beds, walls and slant boards. While the focus is on antique examples, Twentieth Century takes on a pattern underline that the needlework tradition has continued. For example, the “Stars” section includes an eight-pointed variation pieced from hundreds of diamonds with an astonishing ten to 11 stitches an inch and made in the 1970s or 1980s. The craftsman in this case was Larry Gannon (1914-2002) of Jefferson County, an accounts manager who took up quilting on his retirement in 1974. As the accompanying text states, “After World War II, a patriotic interest in traditional American interior decoration inspired revivals of traditional quilt patterns and quilting in general. The first 1950s upsurge, fueled by a renewed interest in arts and crafts during the 1960s, blossomed into a full-blown movement by the United States Bicentennial in 1976. Quilt making reached new heights as a popular social outlet and source of creative expression.”

Over 200 years of quilts – many passed down from generation to generation – are now in the archives of the Tennessee State Museum. “Between the Layers: Art and Story in Tennessee Quilts” dazzles the eye with color and workmanship and, at the same time, reveals the personal journeys of the individual makers responsible for their creation.

The museum is located at 1000 Rosa Parks Boulevard on the Bicentennial Capitol Mall State Park; learn more at www.tnmuseum.org.