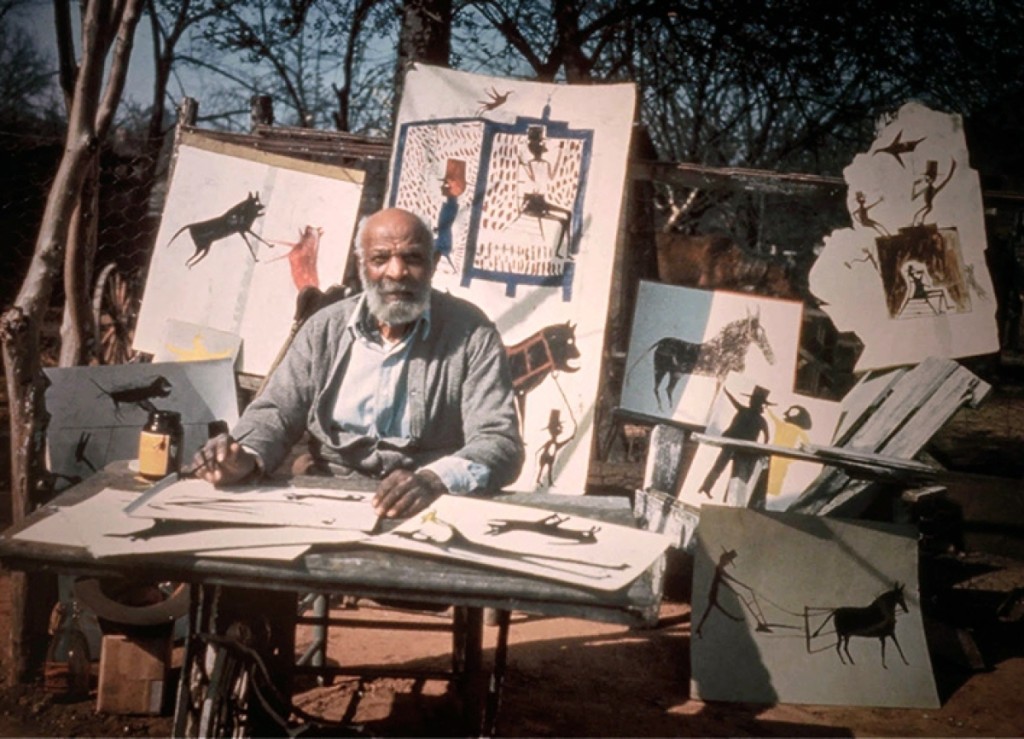

Bill Traylor sits before a display of his artwork. Photograph by Horace Perry. Courtesy Alabama State Council on the Arts.

By Karla Klein Albertson

“Between Worlds: The Art of Bill Traylor,” the current exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through March 17, explores the work of self-taught artist Bill Traylor (circa 1853-1949) in the context of Twentieth Century social and aesthetic history. The project brings together 155 drawings and paintings from the artist’s prolific output, featuring examples drawn from the museum’s own collections and a substantial list of public and private lenders. Lively images of people and animals in motion spring out from the sheets of paperboard decorated with crayon, pencil and opaque watercolor.

The major undertaking was organized by Leslie Umberger, curator of folk and self-taught art at the museum, and is accompanied by her new volume on Traylor’s long life and brief career as an artist. The monograph includes chapters on the world in which he lived, carefully documented by biographical details from surviving records, and discusses the emergence of his talent during an active period in late life while recounting how his preserved work captured the attention of the art world decades after his death.

In the book’s preface, the curator outlined her goals: “From the outset of this research project – which took roughly seven years from inception to execution, to manifest in an exhibition and publication – the intention was to bring together long-separated artworks that are related in content; give in-depth attention to Traylor’s imagery, narratives and symbolism; and carefully revisit the artist’s biographical details to establish a comprehensive and illuminating framework for his body of work… The project entails the most in-depth look at Traylor’s life and art to date, yet it acknowledges that many facts of his life will never be established and the artist’s personal agenda will ultimately remain hidden and enigmatic.”

Artists work with images gathered from their environment, as interpreted by personal thoughts, circumstances and talent. The question arises: how to label Bill Traylor? He was black, a self-taught artist, worked in a “folk” rather than academic tradition and existed as an outsider in relationship to the mainstream art world. Critics and academics continue to wrestle with definitions for these designations. Umberger has a valuable discussion of terms in “Notes to the Reader.”

Artists work with images gathered from their environment, as interpreted by personal thoughts, circumstances and talent. The question arises: how to label Bill Traylor? He was black, a self-taught artist, worked in a “folk” rather than academic tradition and existed as an outsider in relationship to the mainstream art world. Critics and academics continue to wrestle with definitions for these designations. Umberger has a valuable discussion of terms in “Notes to the Reader.”

When his unique style was “discovered” in the second half of the Twentieth Century, Traylor’s life story chained his output within the categories of black folk art or outsider art. Perhaps, had he been born in different circumstances, his art might have been evaluated and labeled in different terms. Just as Jean Michel Basquiat is often defined by his graffiti origins and the volatile New York art world of the early 1980s, Traylor is never discussed without mentioning influences from the segregated Southern world in which he lived. Yet, both have emerged from the “black artist” box to become members in the broader category of important Twentieth Century American artists.

Art historians studying Traylor are in much the same quandary as archaeologists who try to determine the meaning and purpose of ancient artworks without textual support. Although the historical background of his life and painting career has been the subject of meticulous research, determining what he meant by his drawings and paintings at the moment of creation will always entail speculation, as Umberger clearly stated above. The curator chose to open the catalog with a vital introductory chapter, “The Beatitudes of Bill Traylor,” written by African American artist Kerry James Marshall (b 1955), who was born in Alabama, trained in Los Angeles and now lives and works in Chicago.

Marshall explores the difficult subject of black artists lionized by white collectors. And he once again encourages viewers to respond directly to what they see, “In most cases the drawings and paintings, sure and direct, speak for themselves. The more idiosyncratic images, some surreal, others more abstract, well, these are an opportunity for viewers to match wits with the imagination of the maker and construct their own plausible scenarios. Leslie Umberger has provided many tantalizing leads, but the real adventure of finding meaning in Bill Traylor’s art is ours alone.”

“Untitled (Radio)” by Bill Traylor, circa 1940–42. Opaque watercolor and pencil on printed advertising paperboard. Smithsonian American Art Museum, museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment. Photo by Gene Young.

Born into an enslaved family in Lowndes County, Alabama, before the Civil War, Traylor spent most of his life in the rural world of Southern plantation farming, staying on as a paid worker after emancipation. The very name “Traylor” is taken from the family who owned the land. His family life and connections are chronicled in great detail by the exhibition’s companion volume. In the 1920s, he left the agricultural life and moved toward the state capitol of Montgomery. Only in the last decades of his life, when Traylor was in his eighties and living in extremely difficult circumstances on the streets of the black business district, did the artist begin steadily producing the drawings and paintings for which he is now celebrated.

The survival of these fragile works is the most remarkable element of Traylor’s complex backstory. How many were made is unknown, but that any were preserved was thanks to a chance meeting with Charles Shannon (1914-1996), a young art student from Montgomery who saw the elder man at work on his drawings in 1939. In a prescient flash, Shannon recognized Traylor’s remarkable abilities and definitive style in capturing his environment. The younger man encouraged the artist, supplied him with materials, and – most importantly – saved the art works from destruction. After mounting exhibitions in Traylor’s lifetime, Shannon and his wife continued to store the drawings until the time was ripe for their appreciation.

The breakthrough show for Traylor came decades later. In 1982 at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, an exhibition titled “Black Folk Art in America, 1930-1980,” curated by Jane Livingstone and John Beardsley, featured three dozen of Traylor’s works. The catalog for that event is still available, and Traylor’s art has been included in every exhibition of self-taught art since then. By the time of the 2013 single-artist exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum, Traylor was called “one of the finest American artists of the Twentieth Century.” Collectors, dealers and auction houses became involved and individual paintings and drawings today bring five and six-figure prices.

Gallery owner Charles Hammer in Chicago worked directly with the Shannons to represent Traylor’s work. He remembers the excitement when he first exhibited the images at a fair and how collectors were drawn to view what he had available at the gallery. He feels that Traylor’s short working history was a period of release when he felt an immense urgency to say something about his life. When Christie’s published “Outsider Art: The hot list” at the beginning of 2018, a bold Traylor image of man and dog led off the story, after bringing $137,500 in a January sale.

“Between Worlds” has made a fresh start on understanding the artist’s work, rejecting unsubstantiated ideas and invalid connections made by previous analysts of Traylor’s art. Read the detailed background, but – above all – view the art. For artists academic to abstract, creation and depression often exist side-by-side. That Traylor, living in what seemed to be soul-depressing circumstances, should have prolifically expressed himself through such exuberant art, is a tribute to his deep well of creative inspiration. Beyond folk or self-taught labels, Traylor remains a classic artist, in the sense that finished works poured from his hands, regardless of physical circumstances or immediate monetary rewards.

The exhibition runs through March 17th. The Smithsonian American Art Museum is located at 750 9th Street, N.W. in Washington, D.C. For more information, www.americanart.si.edu or 202-633-7970.

Journalist Karla Klein Albertson writes about decorative arts and design.