.jpg)

“Italian Picture Dealers Humbuging My Lord Anglaise” by Thomas Rowlandson, 1812, hand-colored etching, published in London. Gift of Carl Zigrosser, 1974.

By James D. Balestrieri

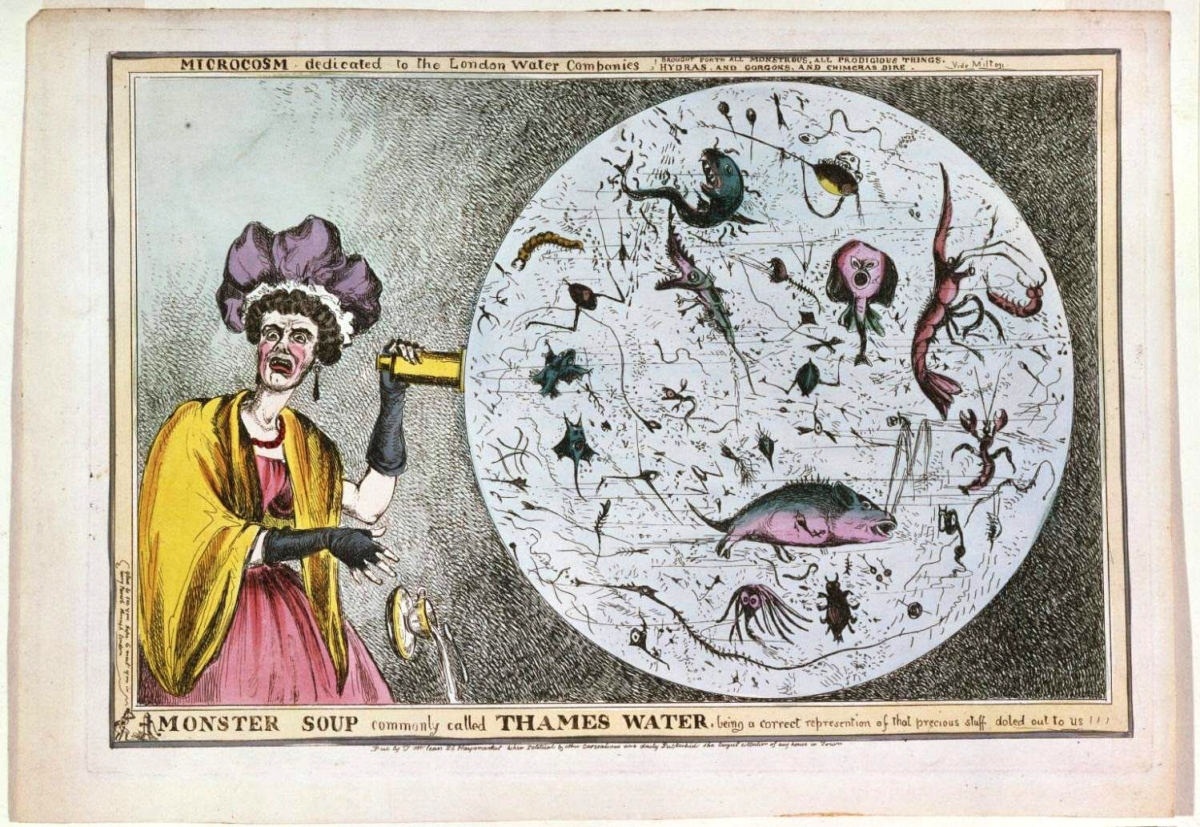

PHILADELPHIA – Foible is a great word. So is folly. Though they are somewhat out of fashion, even dated, the concepts they describe have, perhaps, never been more relevant. And together, foible and folly are the stuff of satire. Satire has been around as long as language and images have been etched in stone and set down on papyrus, foolscap and newsprint. We find satire in literature, in poetry and prose. We find it in painting and sculpture, in song and film, and on the stage. We find satire wherever human frailty inflates and becomes ego, vanity and hubris. The satirist is the court jester of the arts, the one who tells the naked emperor that he has been cheated by his tailors. The caricature is the natural vehicle for the satirical artist.

At the end of the Eighteenth Century, two events rocked the British Empire. First, the infallible core of that empire was shaken by two revolutions, one leading to the loss of Britain’s American colonies; the other, in France, threatening the very centrality of monarchy as the indispensable political system. Second, the new middle class exploded in Great Britain. Rural agrarian society rapidly gave way to urban, industrial dominance. There were new kinds of jobs and people who were identified with those jobs. Alongside this, new money chased the aristocracy in matters of taste, including art and fashion.

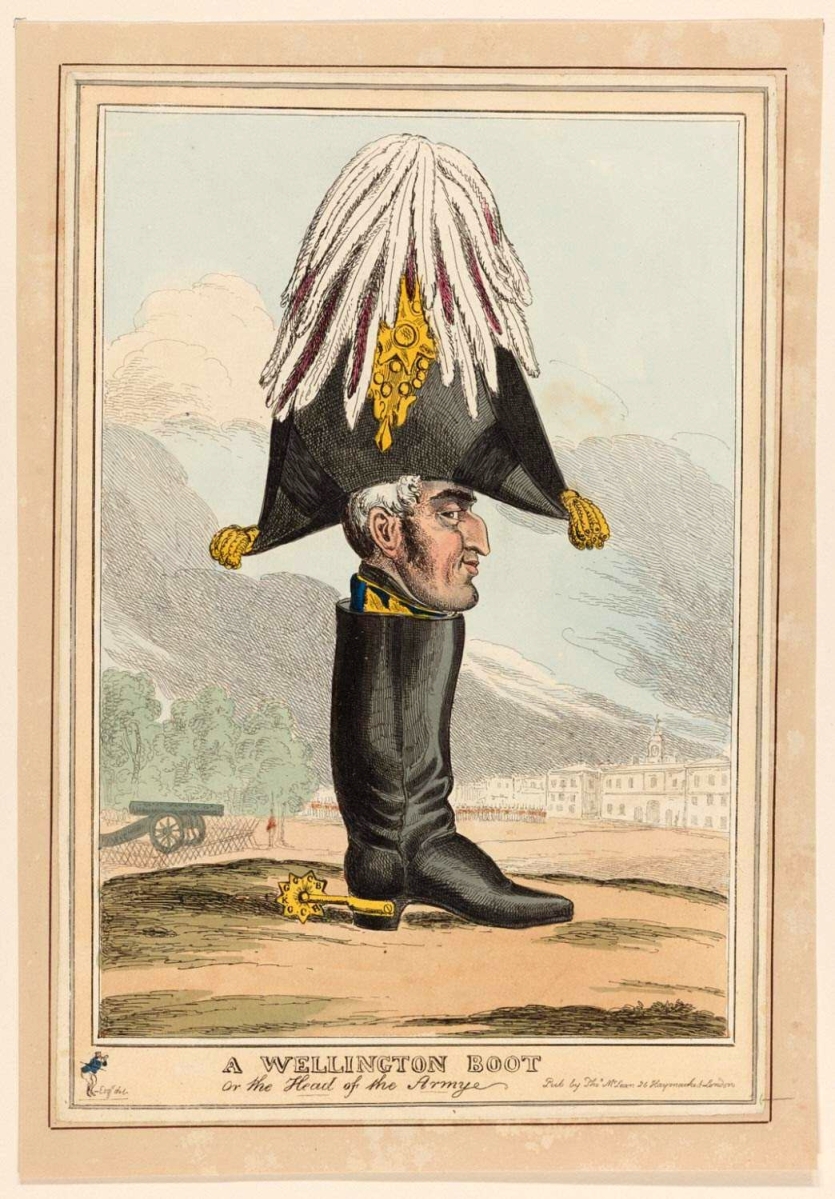

Gossip flew, tastes enjoyed booms and busts, technologies sputtered into being and were ridiculed, classes mixed and wondered about one another. All was ripe for lampooning. Print technologies had made reproduction faster and cheaper, and, like today’s political cartoons and internet memes, satirical images were enjoyed publicly and socially and read like sociological tea leaves to gauge public opinion. As the text of “Biting Wit and Brazen Folly: British Satirical Prints, 1780s-1830s,” on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art through August 22, notes, “While caricatures and satire have been sporadically produced in prints since the Renaissance, such images exploded in popularity in England in the late 1700s. Pasted in shop windows, rented out for a night’s entertainment or sold for private viewing at home, they were everywhere. Often dismissed as trivial ephemera, these social caricatures revealed much about daily life. They provided instant reactions to current events, celebrity gossip and the latest fashions, topics that were unavailable in traditional paintings or royal portraits. Young or old, rich or poor, no one escaped the caricaturist’s sharp eye – the pictures’ subjects were the very audiences who were laughing at them.”

Despite the deliberate exaggerations, the artists who worked in satire and caricature were fine artists, exquisite draftsmen with a keen eye for composition and detail. As early incarnations of sequential art and comic books, they often created suites of images that swirled around single themes.

Following this, the exhibition is organized into four categories of prints: art and connoisseurship, character types, fashion and medicine. Describing the appeal of this approach, organizers say, “Caricature’s popularity also lay in its ability to be interpreted on multiple levels, depending on the viewer’s social class and education. A single picture, for example, might reference Shakespeare while simultaneously depicting crude bodily functions. In this way the most celebrated artists – George Cruikshank, James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson among them – could easily charm both high and low society. What made caricatures powerful then is what makes them relevant now: they turn our everyday anxieties and joys into images that are universal, authentic and perpetually funny.”

James Gillray’s 1796 work “A Peep at Christies;-or-Tally-ho & His Nimeny-pimeney taking the Morning Lounge,” a funny image in itself, requires the curators’ research to unpack its original meaning: “The couple is the Earl of Derby and his mistress, Elizabeth Farren, a celebrated actress, at Christie’s auction house. The subject of the painting reinforces the inappropriate coupling: Derby views an image titled ‘The Death,’ alluding to his own terminally ill wife, while Farren focuses on a young courtesan seducing an ancient Greek philosopher. The title adds another layer. ‘Tally-ho’ evokes Derby’s well-known love of hunting and ‘Nimeny-pimeney’ refers to a play in which Farren famously performed.” Knowing none of that, the idea of wealthy people peering at art and playing at expertise – at Christie’s, no less! – resonates across the years.

James Gillray’s 1796 work “A Peep at Christies;-or-Tally-ho & His Nimeny-pimeney taking the Morning Lounge,” a funny image in itself, requires the curators’ research to unpack its original meaning: “The couple is the Earl of Derby and his mistress, Elizabeth Farren, a celebrated actress, at Christie’s auction house. The subject of the painting reinforces the inappropriate coupling: Derby views an image titled ‘The Death,’ alluding to his own terminally ill wife, while Farren focuses on a young courtesan seducing an ancient Greek philosopher. The title adds another layer. ‘Tally-ho’ evokes Derby’s well-known love of hunting and ‘Nimeny-pimeney’ refers to a play in which Farren famously performed.” Knowing none of that, the idea of wealthy people peering at art and playing at expertise – at Christie’s, no less! – resonates across the years.

Double standards are the meat and potatoes of satire. Thomas Rowlandson’s “Connoisseurs” examines the examiners, the nearest three of whom are at least pretending to appreciate the art as they lean in and leer at the voluptuous nude. But the rearmost appreciator, in purple, stands on tiptoe with a truly lascivious look on his face. His body language conveys what the others conceal.

“Chimney Sweeper,” one of George Cruikshank’s Life in London types, turns the soot-covered sweep into a harlequinade of rags, banging on his shovel with the handle of his broom. Sweeps, like members of other guilds, often had particular cries and songs to advertise their services. The reality for sweeps, who were typically young children small enough to fit into and climb into the chimneys, was not so sprightly. Lung disease, stunted growth and curved spines were the sweeps’ lot. Cruikshank’s sweep, however – like his other characters – has an independent spirit, as if he is an early model for Bert in Mary Poppins.

Satirizing a very new technology, the steam engine, here powering a coach in Robert Seymour’s 1828-30 etching “Going It By Steam,” pokes fun at the swells, flying through the air as the overheated boiler blows. Their attitudes – skirts flying, folded around a pole, doing the splits in red trousers – and their facial expressions – of utter surprise rather than horror – make humor of a tragic situation. What adds to the humor for us is knowing that the steam coach would, in a scant few decades, become the automobile. From our vantage point, we satirize the satirist, who would surely join us in a good-natured laugh at his expense.

As I laughed at Gillray’s “Following the Fashion,” I first remembered a scene in Neil Simon’s The Goodbye Girl, where Marsha Norman’s character tries to remake the contested apartment after a photograph in a magazine. Her heroic efforts fall short. And then I remembered my own folly building models, thinking, erroneously, that they would come out looking like the pictures on the boxes. But women were not alone in following the vanities of fashion and taking risks to look good, as is evidenced in William Heath’s “An Alarming Discovery Showing the Fatal Effects of Using Cosmetics” where it truly isn’t easy being green.

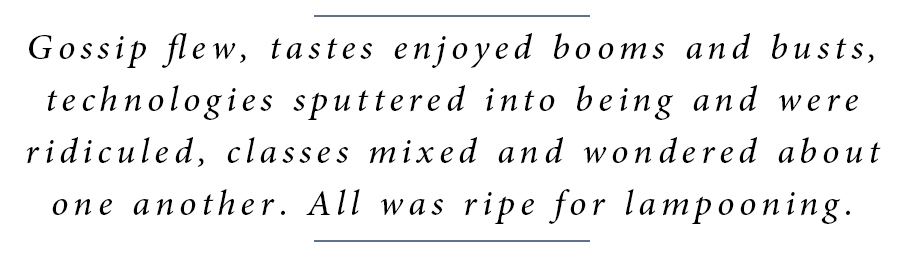

During this period, women were also becoming more educated, often to the consternation of an acutely patriarchal society. Charles Williams’s “Advantages of a Modern Education” makes sport of the novel-reading housewife whose hearth is afire and whose dinner is being borne off by the family dog and cat while she sits engrossed in a book. On the pile of books, the title of one, Sir Walter Scott’s The Heart of Midlothian, leaps out. Featuring a strong female protagonist out to clear her sister’s name, we can see how the housewife might be deaf to the parrot in his cage who cries, “Cook, cook, there’s fire.”

“Advantages of Modern Education” by Charles Williams, 1825, hand-colored etching. Published by S. Knights, London. Gift of David Gwinn, 1963.

In a meta moment worthy of social media, “Very Slippery Weather,” an 1808 etching by Gillray, onlookers gawk at a window full of satirical prints, oblivious to the chap who has just slipped on slick pavement. Wig off, gold spilling from his pocket, he would seem to be an easy mark, yet no one robs or helps him. They are too involved watching funny videos – no, looking at hand-colored prints – to notice.

We should not neglect the skill and effort of the etchers who took the original drawings and etched them onto copper plates, nor the efforts of the printers and those who painstakingly colored these works. If the artists created them, the etchers, printers and limners made them enduringly popular.

Once upon a time, these satirical prints were widely collected. Doctors, for example, collected and displayed the medical prints, such as Gillray’s “Gout,” with its fanged and clawed devil monster representing that pain came with too much port and too little exercise. These days, they are not as popular – or as expensive – and one hopes that exhibitions like “Biting Wit and Brazen Folly” help restore some of their former luster as desirable objects.

The Eighteenth Century also saw the rise of the notion of the individual self as a unique, independent entity. How we see ourselves, is, of course, not how others see us. The gap between how we want to be seen and how we are seen is often more of a yawning canyon. We imagine ourselves fashioned as facets of a diamond, when in fact those facets, viewed from without, are little more than flimsy cards in a precarious house that would fall before a puff. Satire, in the form of the caricaturist, wades right into that canyon and blows our house of cards down. It’s a cliché today that all we need do to succeed is remember these three words: believe in yourself. Satire blows right by belief and goes for the jugular of the self, where all your foibles and follies hide from you. And remember, it is always best, when the satirist points in your direction, to laugh with the joke. Fighting it only makes the laughter louder.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art is at 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway. For more information, www.philamuseum.org or 215-763-8100.

Playwright, author and critic James D. Balestrieri is director of J.N. Bartfield Galleries in New York City.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)