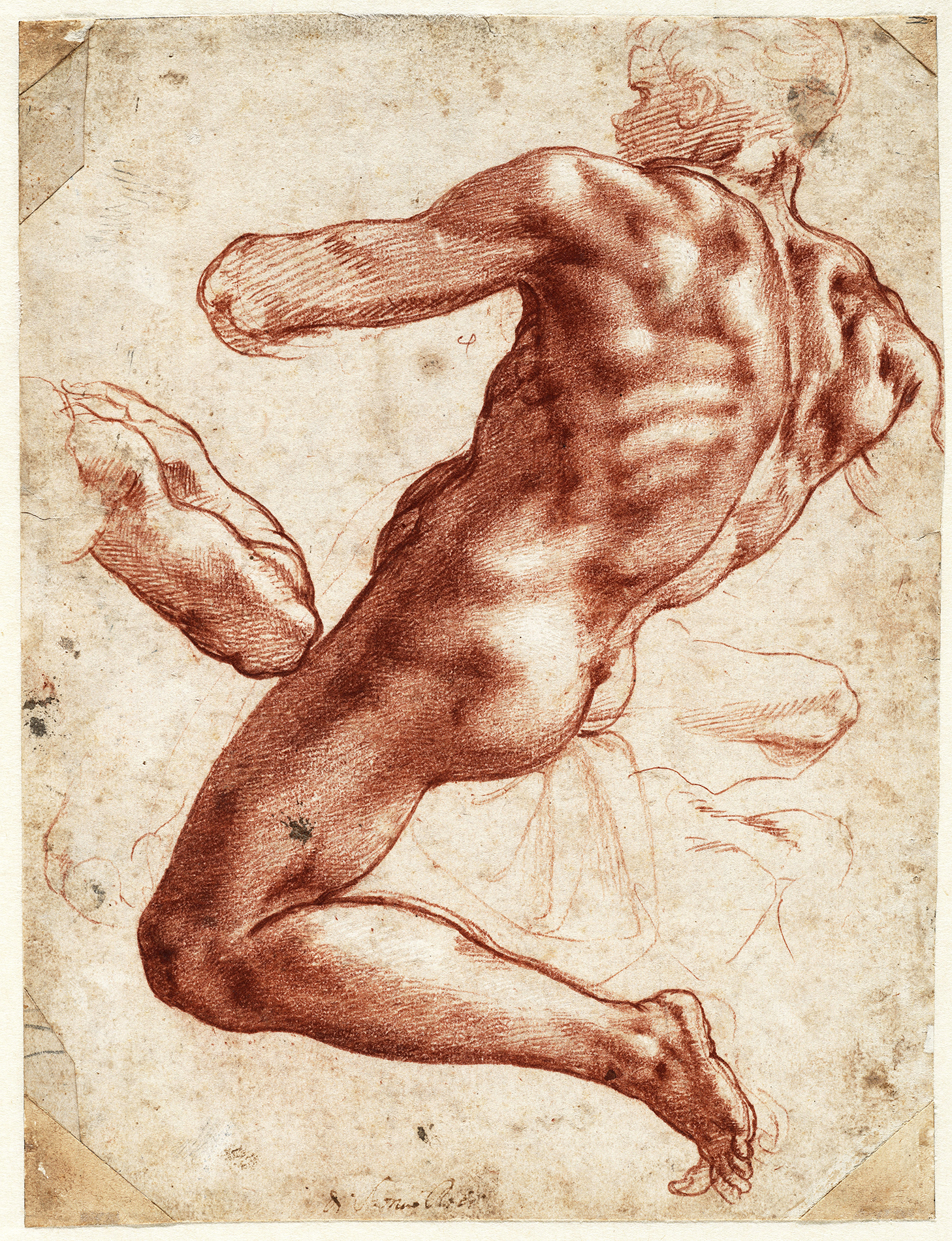

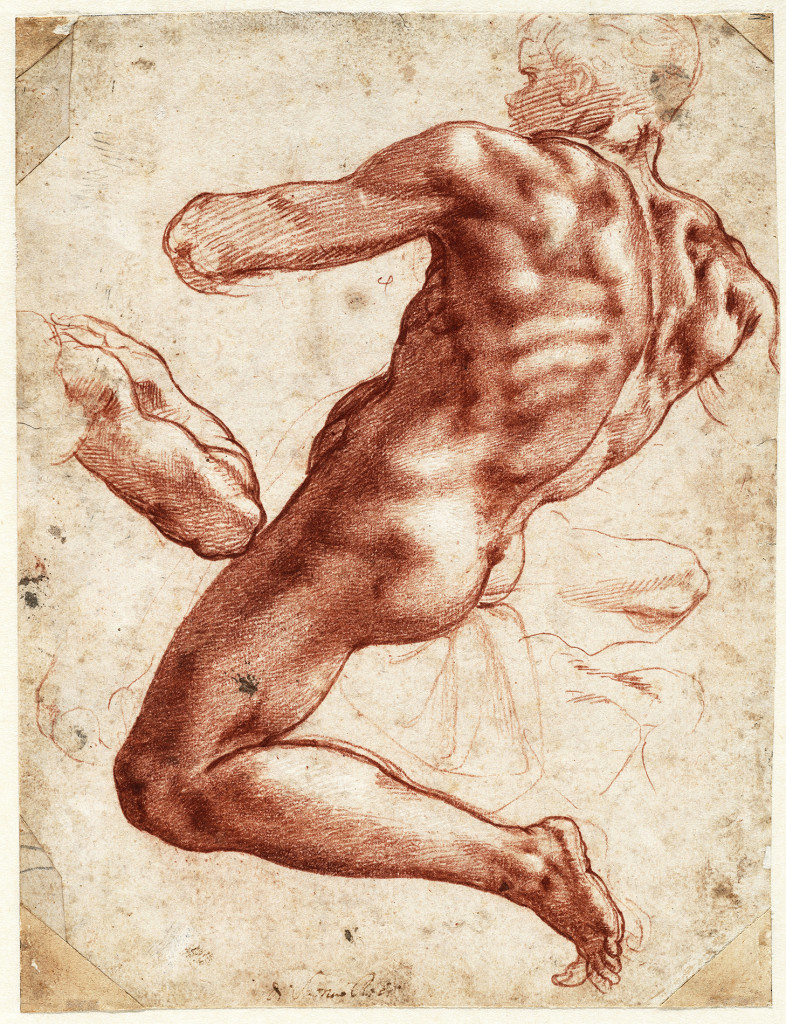

“Seated Male Nude (study for the Sistine Chapel ceiling)” by Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564), circa 1511. Red chalk with highlights in white lead, 27.9 by 21.4 centimeters. Teylers Museum, purchased in 1790. ©Teylers Museum, Haarlem.

By James D. Balestrieri

CLEVELAND, OHIO – As the exhibitions, essays and reconsiderations mount in the quatercentenary of his birth, it seems to me that Leonardo Da Vinci approached and solved artistic problems scientifically and scientific problems artistically. This is what is troubling about the orb in the legendary (and now apparently invisible) “Salvator Mundi” – the optics are unscientific and the handling of the reflection seems inartistic. By contrast, Leonardo’s contemporary and rival, Michelangelo – who is not to be denied even in Da Vinci’s big year, as we shall see – seems to approach and solve artistic and scientific problems anatomically. That is, he sees and measures the world’s phenomena in terms of and against the architectonics of the human form.

Building on the recent blockbuster Michelangelo drawing exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Michelangelo: Mind of the Master,” now on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art, presents 28 works from its own collection and a breathtaking selection on a rare loan from the Teylers Museum in Haarlem, the Netherlands.

The catalog contains a brief essay on the history of the Teylers museum and another describing the provenance and wanderings of the Michelangelo drawings that are housed there. A true product of the Enlightenment first opened to the public in 1784, the Teylers is a veritable “museaum,” a seat of the muses, a collection of objects of art, science and natural history that is meant not only to teach and amaze, but to inspire. The muses live there, inhabiting the objects, and those who enter are meant to be charged with their energies as they go back out into the world. The Michelangelo drawings themselves were once owned by Queen Christina of Sweden, a highly educated patron of the arts and sciences who eventually abdicated the throne, converted to Catholicism, moved to Rome and became a vital part of the city’s artistic and political life. Carel van Tuyll van Serooskerken’s essay on the history of the drawings suggests that they were passed down from artist to artist after Michelangelo’s death until they reached a Dutch merchant who offered them to the queen. Bequeathed to one of the Cardinals in Rome, they passed from hand to hand until they entered the Teylers collection in 1790. From a book that had contained perhaps 100 drawings, only 32 remained.

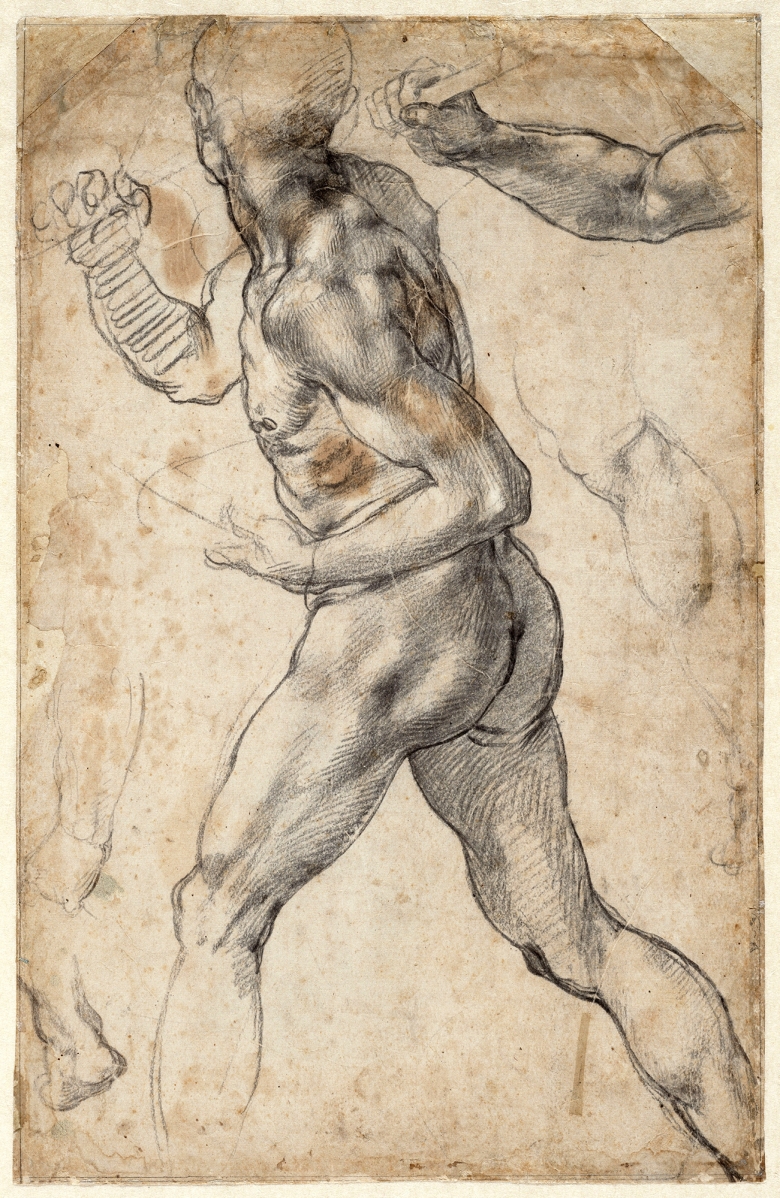

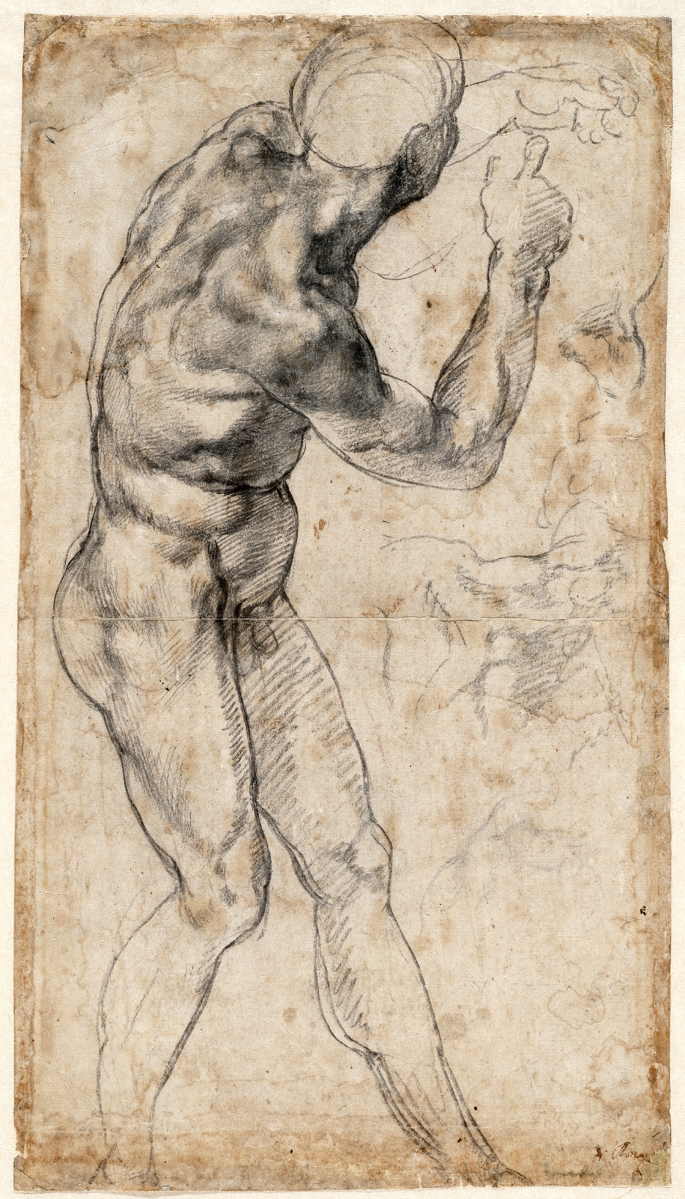

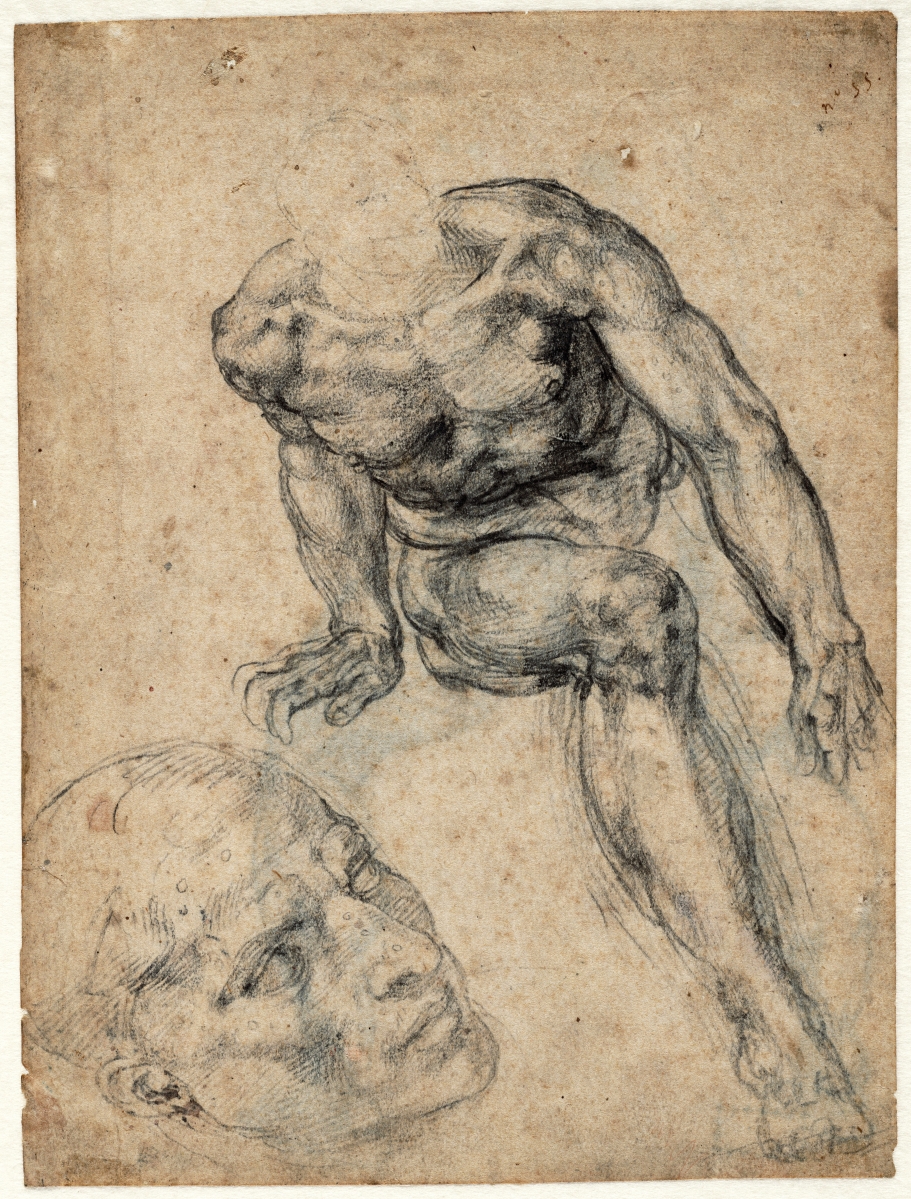

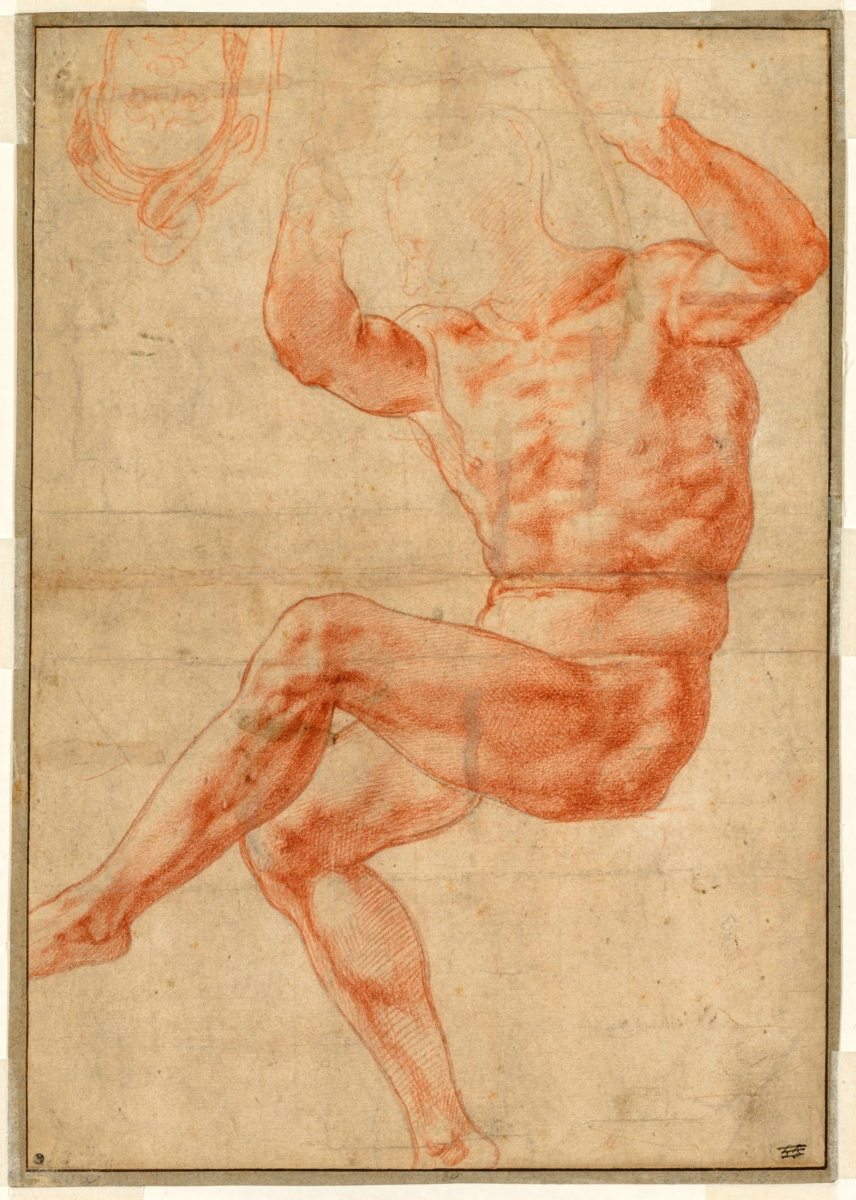

Michelangelo believed that humankind was God’s most perfect creation. To imitate the human body was, therefore, the artist’s highest calling, and was the nearest art could get to God. But this notion of imitatio, as the Italian Renaissance masters understood and practiced it, came to have a specific meaning that transcends the concept of imitation as copying. In her catalog essay “Michelangelo: The Human Form in Motion” exhibition curator Emily J. Peters explains imitatio as she discusses two of Michelangelo’s studies for the never completed “Battle of Cascina” fresco. “Study of a Striding Male Nude” and “Male Nude, Turning to the Right,” demonstrate, as Peters writes, that whether the artist worked from live models or not, he surely exceeded and idealized what was in front of him: “The bodies of these figures pulse with life, but it is life poured into a sculpture: stone enlivened. These monumental figures embody the artist’s unique talent for assimilating classical sculpture and nature’s primo modello (the human body made in God’s image) in a process combining memory and invention. Like a glorious declaration of his own ambition, the figures not only imitate nature, but attempt to improve upon it, a process called imitatio (imitation), for which Michelangelo would become the paradigm among his contemporaries.”

Looking at these two drawings, seeing how the figures would have fit in the overall mural composition, which only survives in copies and prints, you have to picture the scene: Michelangelo, the upstart, working on one wall of the Sala del Gran Consiglio in Florence’s Palazzo della Signoria while Leonardo, the elder statesman, on the opposite wall, labors on his commission depicting the Battle of Anghiari. That this battle of titans striving to capture and depict famous military triumphs ended without issue when Michelangelo was summoned to Rome and Da Vinci was called to Milan seems thoroughly unjust.

For both Da Vinci and Michelangelo, representing the torsion of the human body in motion, twisting in space, was a paramount concern. The body under stress, to them, expressed the inner life of the subject, the emotion of the moment, time stopped in an instant of revelation. For Da Vinci, gesture and pose, and the sfumato technique that blurs the edges between things locates the body in nature. This, in turn, expresses the psychology of the subject. For Michelangelo, strain and sinew just as they are about to burst from the skin, and the lines that then define the subject’s limits – we might call this anatomy against nature – are what ultimately externalize and express that subject’s inner humanity.

For both Da Vinci and Michelangelo, representing the torsion of the human body in motion, twisting in space, was a paramount concern. The body under stress, to them, expressed the inner life of the subject, the emotion of the moment, time stopped in an instant of revelation. For Da Vinci, gesture and pose, and the sfumato technique that blurs the edges between things locates the body in nature. This, in turn, expresses the psychology of the subject. For Michelangelo, strain and sinew just as they are about to burst from the skin, and the lines that then define the subject’s limits – we might call this anatomy against nature – are what ultimately externalize and express that subject’s inner humanity.

The preparatory drawings that Michelangelo and Da Vinci did for the Palazzo della Signoria proved to be a primer for artists throughout Europe. How inspiring would the finished frescos have been? We can only imagine.

As opposed to Da Vinci, who valued – and sold – his drawings and sought to preserve his notebooks, Michelangelo was determined not to let the world see his process. He believed that his reputation would be enhanced if it seemed that his work was almost divinely inspired, that it sprang whole, a final product in its ultimate form, like Athena from the head of Zeus. Some 600 extant drawings – out of what must have been tens of thousands – are now attributed to Michelangelo. He appears to have shared most of these, generously, with other artists who used them for study and as design ideas for their own works. Others appear to have been purloined, snatched from the flames to which he often consigned his studies.

The exhibition stresses the newness of drawing as paper became available as a cheaper alternative to vellum and parchment. Red and black chalks became part of the artist’s toolkit and the idea of disegno, meaning both drawing and design, enters the aesthetic vocabulary. To cherish drawings, as Da Vinci seemed to do, might have made him the outlier in his time. For Michelangelo, the disegno is a tool, a means to a greater end, something to be used and discarded. His drawings are almost always double-sided, scrawled on and over. He would take scissors to parts of his drawings that didn’t please him, glue new paper over the gaps, and press on with his work. When we see his drawings, we truly are looking into the mind of a master who didn’t want us to see his mind at all.

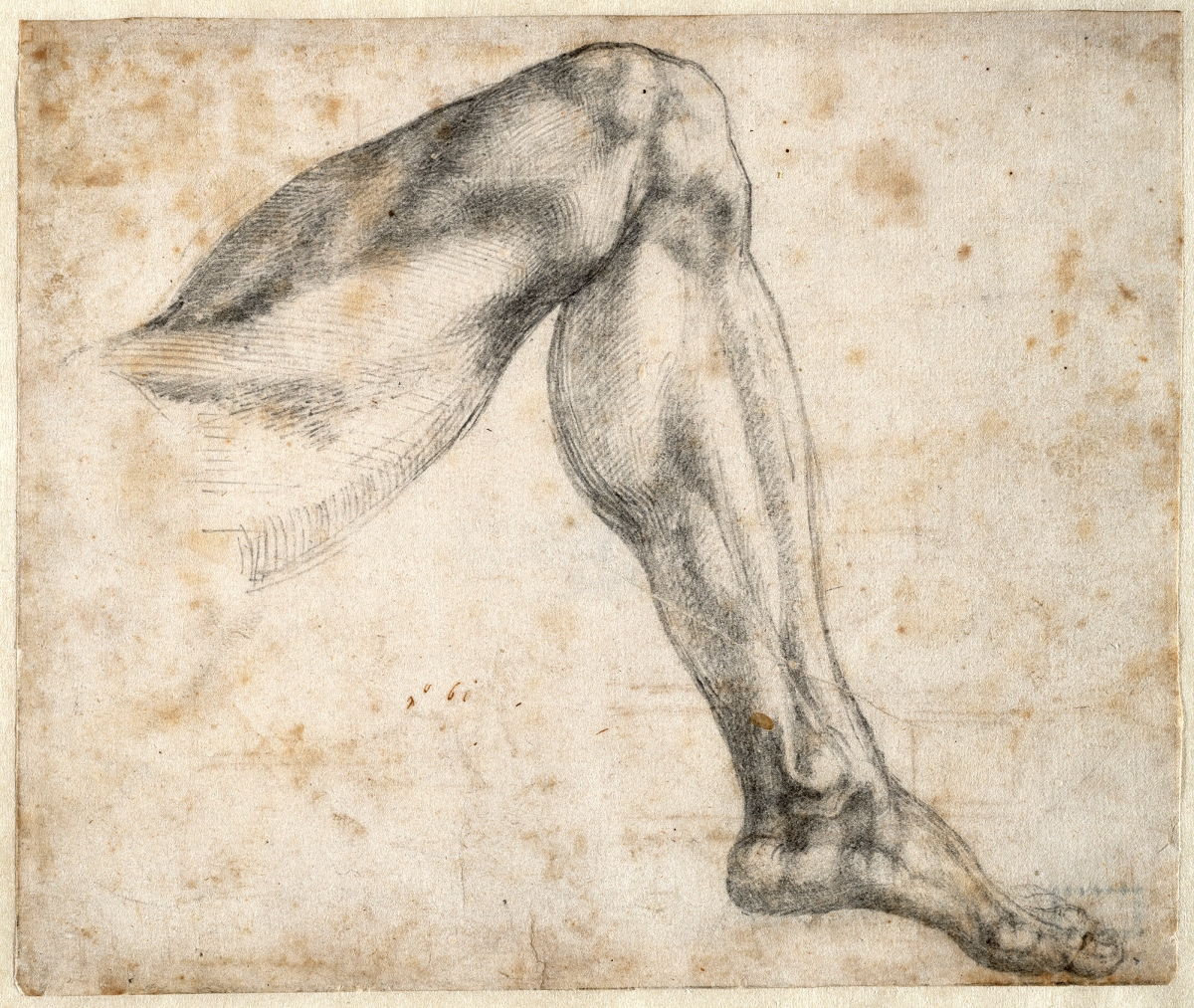

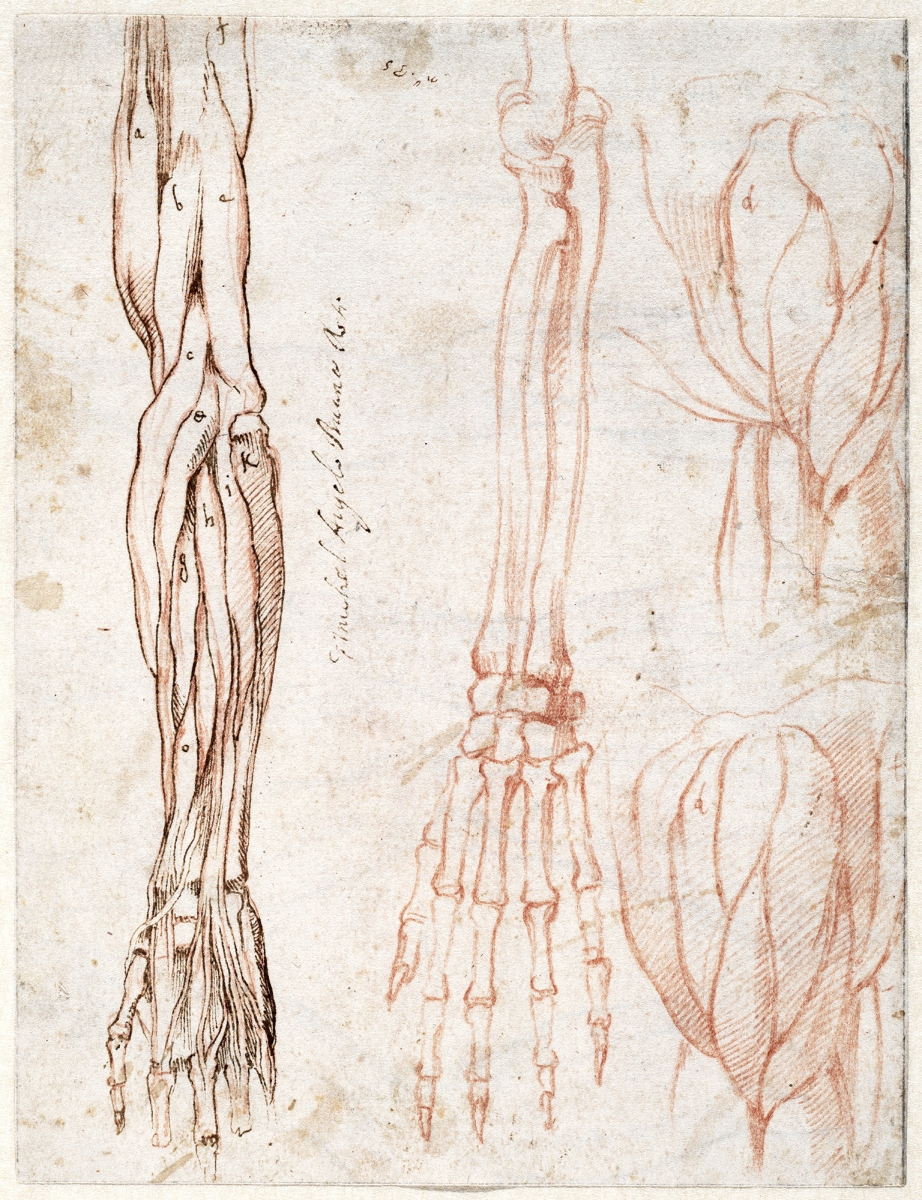

Like all artists of the Renaissance, anatomy was a key component of instruction. But Michelangelo pushed further into the study of the human body than most of his peers – Da Vinci excepted – anticipating Rembrandt and others in his belief that scientific understanding of what we call biomechanics was essential to the practice of art. Vasari, the contemporary and great biographer of the Italian Renaissance masters, asserts that “Michelangelo took part in a human dissection at the Santo Spirito hospital in the 1490s, writing, ‘in flaying dead bodies, to study anatomical matters, [Michelangelo] began to perfect the great sense of disegno that he later acquired.'” “Studies of a Left Arm and a Shoulder,” a drawing executed circa 1515-20, shows that the artist maintained a keen interest in the structure of human body throughout his career.

“Three Draped Figures with Hands Joined” by Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, 1475-1564), 1496-1503. Pen and brown ink, 26.9 by 19.4 centimeters. Teylers Museum, purchased in 1790. ©Teylers Museum, Haarlem.

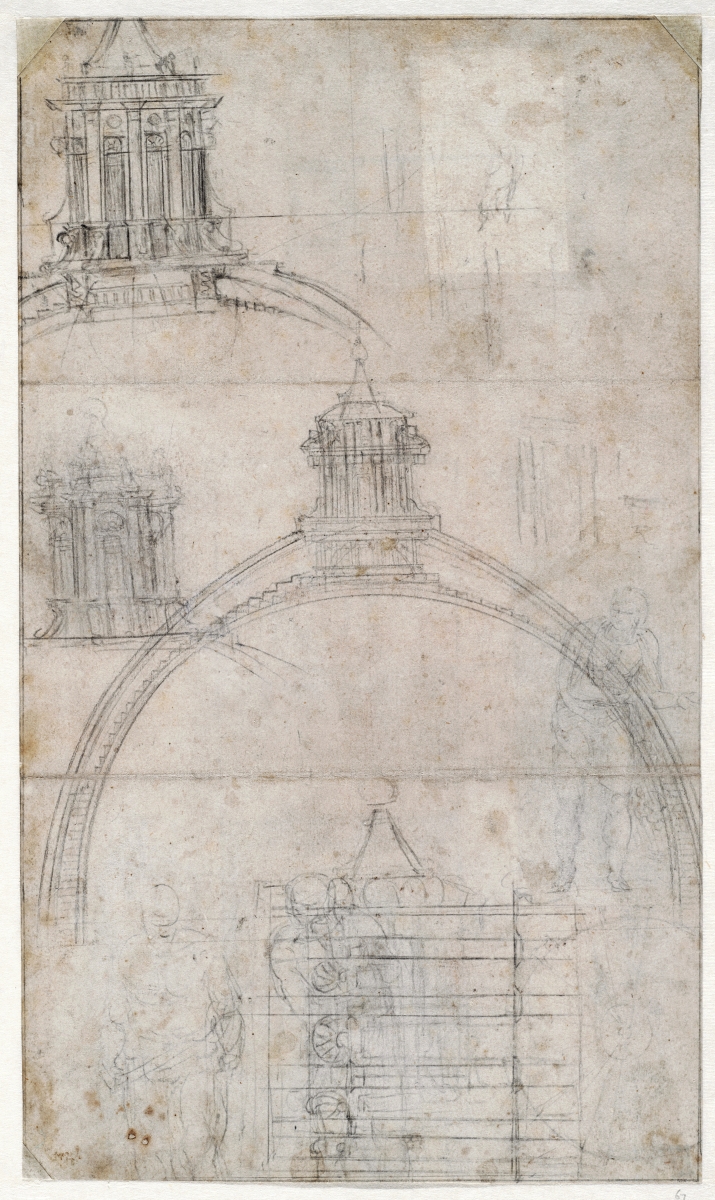

The ceiling of the Sistine Chapel needs no introduction. In its magnificent panels, the central episodes of the Judeo-Christian narrative of creation and salvation is expressed in terms of the human body in space. Michelangelo’s masterpiece accommodates the architecture of the chapel, fusing the story, his “telling” of it, and the space into a single, unified vision. Figures strain against and burst from the curvature of the rectangles, spandrels and pendentives, springing directly from Michelangelo’s belief that the pinnacle of beauty and harmony is to be found in the human body. Peters writes, “Michelangelo himself made the epistemological connection between the human form and architecture, writing in a letter around 1550 that ‘it is a certain thing, that the members of architecture derive from the members of man. Who has not been or is not a good master of the human body, and most of all of anatomy, cannot understand anything of it.’ For Michelangelo, shape, proportion, and space were always rooted in the human body.” A number of extant drawings, including “Section through the Dome of Saint Peter’s with Alternative Designs for the Lantern and Figure Sketches,” demonstrate Michelangelo’s precept. The scaffolding over the drawing of the male nude at the bottom of the page seems to inspire the view of the edge of the dome. Michelangelo transmutes the outline of the head, shoulder and knee of the figure into the corner, cornices and ornaments on the dome.

One last look, “Seated Male Nude (study for the Sistine Chapel ceiling),” an ignudo painted near the “Persian Sibyl” but perhaps is more closely connected to the panel depicting the “Separation of the Earth from the Waters.” In red chalk heightened with white, Michelangelo exposes every muscle and bone; the strain on the body does not simply represent the rending of elements, it is the rending of elements: solid bone and supple muscle and skin is solid rock and supple earth, compelled by God to tear themselves from flowing blood and the fluids of the body that are the flowing fresh and salt waters of the world. Here, for Michelangelo, the human body is the universe, and the universe is the human body.

The Cleveland Museum of Art is at 11150 East Blvd. For more information, www.clevelandart.org or 1-877-262-4748.