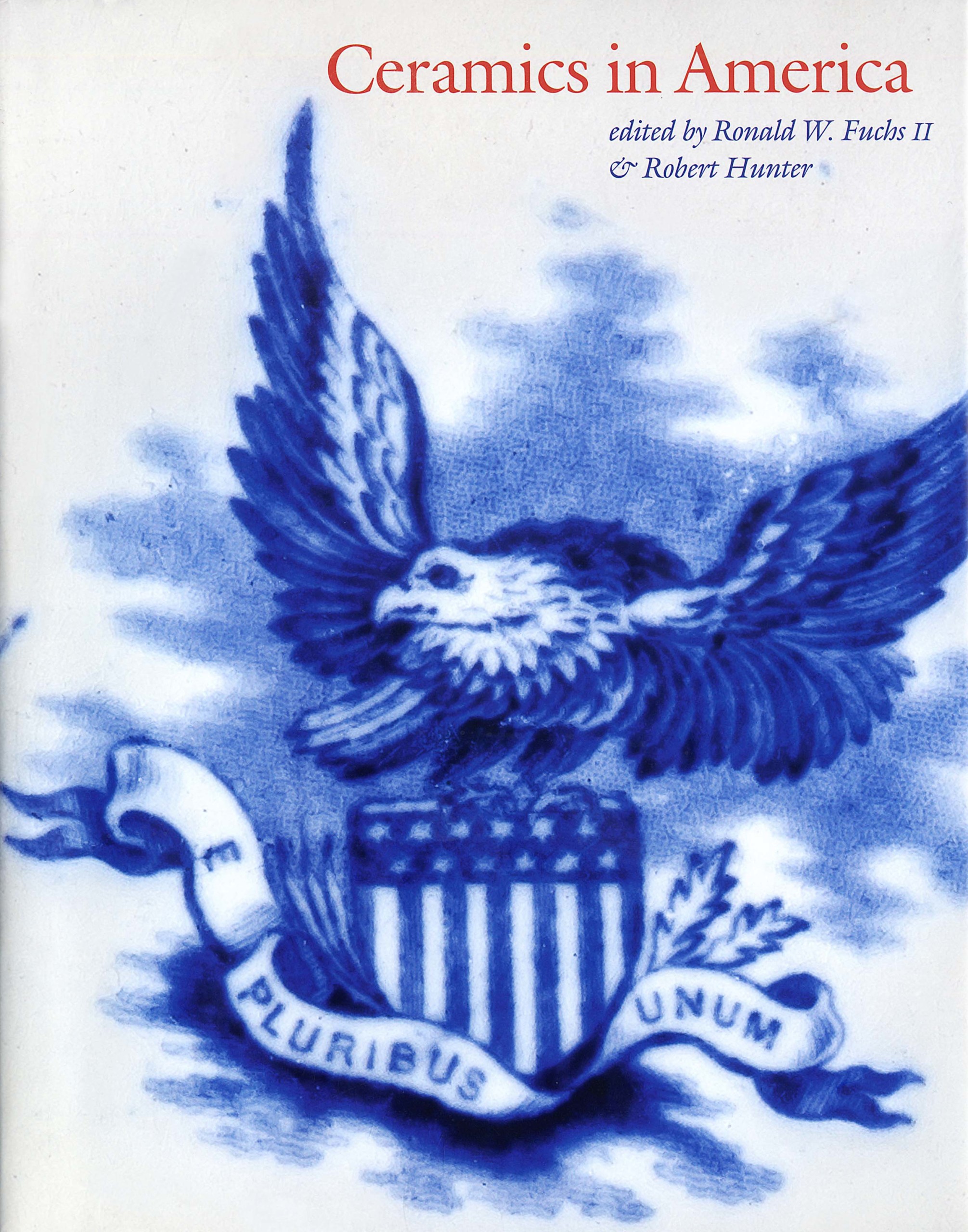

Ceramics in America edited by Ronald W. Fuchs II and Robert Hunter, with contributions by Leslie M. Harris, A. Brandt Zipp, Mark Shapiro, Christopher Pickerell, Margi Hofer & Allison Robinson, Patricia F. Ferguson, Cassandra A. Good & Adam T. Erby, Robert Hunter, Jill Weitzman Fenichell, Ronald W. Fuchs II, C. Wesley Cowan & Stephen C. Compton, Al Luckenbach and Deborah L. Miller & Ronald W. Fuchs II. Published by The Chipstone Foundation, Milwaukee, Wis., 2024, 258 pp, $65, hardcover.

By Madelia Hickman Ring,

NEWTOWN, CONN. — With spring comes warmer weather, Easter and Passover… and the latest volume of the Chipstone Foundation’s ceramics journal: Ceramics in America. Like the 2023 volume (reviewed in the May 17 issue of Antiques and The Arts Weekly), this issue is co-edited by incoming editor Ronald W. Fuchs II, and outgoing longtime (and founding) editor, Robert Hunter.

In his introduction, Fuchs maps out the essays featured, acknowledges Hunter and his unflagging commitment to the field of ceramics and pledges to revive in future issues the “New Discoveries” feature of the publication.

The issue dedicates about 80 pages to articles on Thomas Commeraw, by five authors, beginning with an essay by American historian, Leslie M. Harris. In “New York City in the Era of Thomas Commeraw,” she details the historical context of the New York City Commeraw lived in, as well as his circumstances as an enslaved and later manumitted potter — with his parents and two siblings — in the household of white potter, William Crolius, Jr. She identifies Commeraw as being singular in that he eventually owned his own home and business.

Mark Shapiro working up the second side of a Thomas Commeraw-style jar with free-standing handles. Eli Liebman photo.

Scholarship on Commeraw began in the early 2000s, when A. Brandt Zipp, ceramics scholar and partner with his parents and brothers at the Crocker Farm auction house in Sparks, Md., made the critical discovery that Thomas Commeraw was Black, rather than a white potter of European descent as the antiques world had previously presumed. Zipp’s essay, titled “Putting Thomas Commeraw Together Again: A Brief Meditation on Two Decades of Research,” walks readers through the paths his research has taken.

Contemporary potter Mark Shapiro first became familiar with Commeraw when he was a Smithsonian artist resident fellow at the National Museum of American History; he supplies an extensively-illustrated photo essay documenting the steps Commeraw likely took while making a jar with free-standing handles.

Christopher Pickerell does a deep dive into a rare surviving form Commeraw is known to have made: cylindrical stoneware jars fashioned to hold pickled oysters, a favored delicacy among wealthy landowners and sea-going captains, who also used the oysters to barter with. The cylindrical form is identified by Pickerell as being an easy one to turn quickly and fire in large quantities; Commeraw was the first to incorporate the names of the Black oystermen on his pots.

Wrapping up current research on Commeraw, scholars Margi Hofer and Allison Robinson’s essay “Collecting Commeraw” explore the early collectors, ceramic historians and museum curators that were first attracted to Commeraw’s vessels and a timeline of when his works were acquired by various museums.

Oyster jar by Thomas Commeraw, New York City, 1799-1804, salt-glazed stoneware, 5¼ inches high. Courtesy Christopher Pickerell, Rory MacNish photo.

“‘Slave Candlesticks’: Illuminating British Patronage and Racism in the Mid-Eighteenth Century” by ceramics scholar Patricia F. Ferguson is an apt segue that steps away from discussing Commeraw to address the image of enslaved Blacks as a popular decorative motif. Following a discussion of the few potteries and forms made, she poses the important, if probably unanswerable, question: “How did these pieces resonate with real Black servants or the Black workers in the manufactories that made them?”

The recent discovery at auction of an allegorical Parian figure titled “La Peinture (Painting)” that was part of a larger group commissioned in Paris from the Manufacture du duc d’Angoulême in 1790 to grace George Washington’s dining table in Philadelphia prompted Cassandra A. Good and Adam T. Erby’s article, “La Peinture: The Rediscovery of George and Martha Washington’s Presidential Biscuit Porcelain Figures and Their Hidden History.” Here, the authors recreate the weekly allegorical tablescape that heralded the aspirations of the newly-founded republic that would have been seen by visiting congressmen, diplomats and other dignitaries who dined at the Washingtons’ Philadelphia home towards the end of his presidency.

Robert Hunter may have titled his essay simply “About Face Vessels,” but there is nothing simple about his lengthy discourse that begins with the earliest appearances of the form in Ancient Greece and ends with face jugs made by contemporary Southern potters.

Candlesticks depicting “Tom et Evangeline” (left) and “La fuite d’Elise” (right), attributed to Hace et Pépin-Lehalleur, Vierzon, France; retailed by Haughwout and Dailey, New York City, 1853-70, biscuit and glazed hard-paste porcelain, 8½ inches tall. Courtesy, collection of Brooke Eastlick, Gavin Ashworth photo.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s influential novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) is largely credited with being the first book about slavery by a white writer to depict slavery with dignity, and its popularity spawned a broad range of mementoes, from household goods to printed tapestries and more. Jill Weitzman Fenichell discusses new findings of figural porcelains that feature characters from the book, while Fuchs briefly discusses a rare Worcester Parian porcelain figure showing Uncle Tom and Eva reading.

An examination of an abolitionist Staffordshire mug is Hunter’s second article submission. The primary documentation found by dealers Bob Zordani and Heidi Kellner are a case study for the historical context in which the mug — and other abolitionist ceramic wares — were made.

Plate, Bristol, England, circa 1700-1730, tin-glazed earthenware, diameter: 7-1/8 inches. Al Luckenbach collection, Al Luckenbach photo.

C. Wesley Cowan and Stephen C. Compton argue that an alkaline glazed stoneware beverage cooler — that bears the unusual inscription “Colored Republicing [sic] Club July 7, 1892” — was probably made in Edgefield, S.C., based on its double-rimmed collar and alkaline glaze. The authors’ discussion of Black political clubs in the last years of the Nineteenth Century provides a vivid context for its creation.

In the penultimate article, Al Luckenbach walks readers through a collection of early Delftware he and his wife, Donna Ware, acquired over a 25-year-period, all with squirrel motifs.

Finally, the issue concludes with Deborah L. Miller & Fuchs’ exploration of ceramics made in at the end of the first quarter of the Nineteenth Century, to commemorate the national 24-state US tour made between 1824-25, by Marie-Joseph-Paul-Yves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis of Lafayette (1757-1834), the last surviving general of the American Revolution. Owned predominantly by members of the middle class, they were viewed as an expression of the values of liberty and the democratic government.

Jug marked “Welcome LaFayette The Nation’s Guest and Our Country’s Glory” by Ralph and James Clews, Staffordshire, England, 1825-30, pearlware, 6½-inches tall. Courtesy Independence National Historic Park, Mike Myers photo.

[Editor’s note: Issues may be purchased at www.casemateacademic.com/9781737717546/ceramics-in-america-2024/. The 2024 issue of the Chipstone Foundation’s other publication, American Furniture, is in the final stages of production but a release date has not yet been announced.]