Part two of our holiday book review list continues on with Darlings of Dress: Children’s Costume 1860–1920, Ben Wilson: From Social Realism to Abstraction, The Hidden Art: 20th- and 21st-Century Self-Taught Artists from the Audrey B. Heckler Collection, Gauguin: Artist as Alchemist, Renoir and Friends: Luncheon of the Boating Party. See more book reviews here.

—

Darlings of Dress: Children’s Costume 1860–1920 by Norma Shephard; Schiffer Publishing Ltd, www.schifferbooks.com, 2017; 192 pages, hardcover, $34.99

This nostalgic look at children’s costume, from 1860 to 1920, reveals diverse cultural influences on its manufacture and design. Written by the prolific author Norma Shephard, who is the founder and director of the Mobile Millinery Museum & Costume Archive, Darlings of Dress features more than 300 historic photographs, fashion plates and selections from vintage catalogs and magazines.

With an additional 115 color images, see infants in period dress, school-aged and teens fads from throughout the late Nineteenth to the early Twentieth Century.

Learn about the history of clothing use and development, fabric types, conservation and storage of textiles and artistic inspiration, all arranged by decade. All types of clothing are represented, including christening gowns; boys’ breeches, knickerbockers and sack suits; swimwear and underwear; bloomers and blouses; fur, feather boas and frocks; sailor suits and uniforms; collars and belts; capes and hoods; lingerie and dresses; sweaters and cardigans; overalls; and many more.

Whether interested in the clothing children wore in 1920, or wore to church in the Victorian era, this reference book will answer questions and give examples in photographs or illustrations.

A fun and nostalgic look at the children’s lives through the clothing they wore. —AK

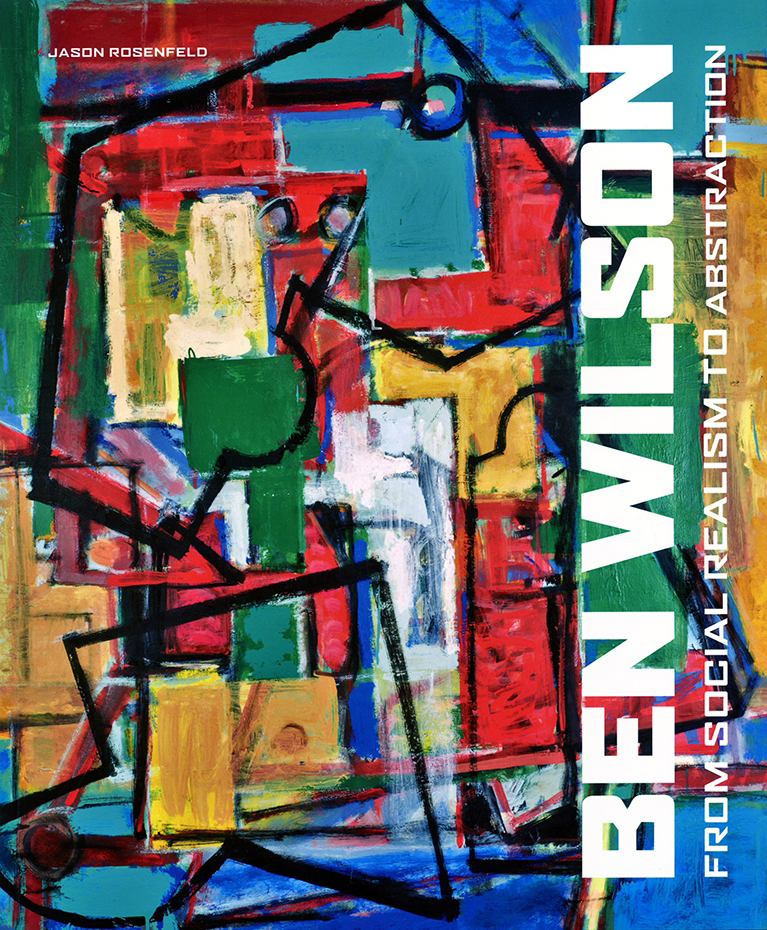

Ben Wilson: From Social Realism to Abstraction by Jason Rosenfeld; George Segal Gallery, Montclair State University, www.montclair.edu/arts/university-art-galleries-george-segal-gallery or www.benwilsonamericanartist.org, 2017; 74 pages, soft cover, $20.

Ben Wilson (1913–2001) is a painter whose work and life reflect the arc of Modern art in the Twentieth Century. Although recognition eluded him, unlike his contemporaries like Jasper John, Mark Rothko and Robert Rauschenberg, this catalog and the exhibition it reflects are just the beginning of the rediscovery of this American artist. The breadth of the work included reveals a personal aesthetic that goes beyond artistic movements and currents — Wilson was an artist who began as a Social Realist with his contemporaries in the WPA and then branched off into a “geometric abstractionist with an unpredictable use of color,” as author and curator Jason Rosenfeld said in his essay that introduces Wilson.

The works here are centered on the gift from Joanne Wilson Jaffe to the George Segal Gallery at Montclair State, with additional loans from private and public collections. The gift from the artist’s family of a substantial portion of Wilson’s complete body of work ensures that the process of rediscovery will continue through exhibition, study and critical analysis.

Although a very slim volume, it is well printed and offers a complete introduction to an artist whose work has been sidelined but fortunately, not forgotten. A checklist of the exhibition and a chronology of Ben Wilson’s artistic life round out the book. All the works in the exhibition were donated to Montclair State by the Ben and Evelyn Wilson Foundation. —AK

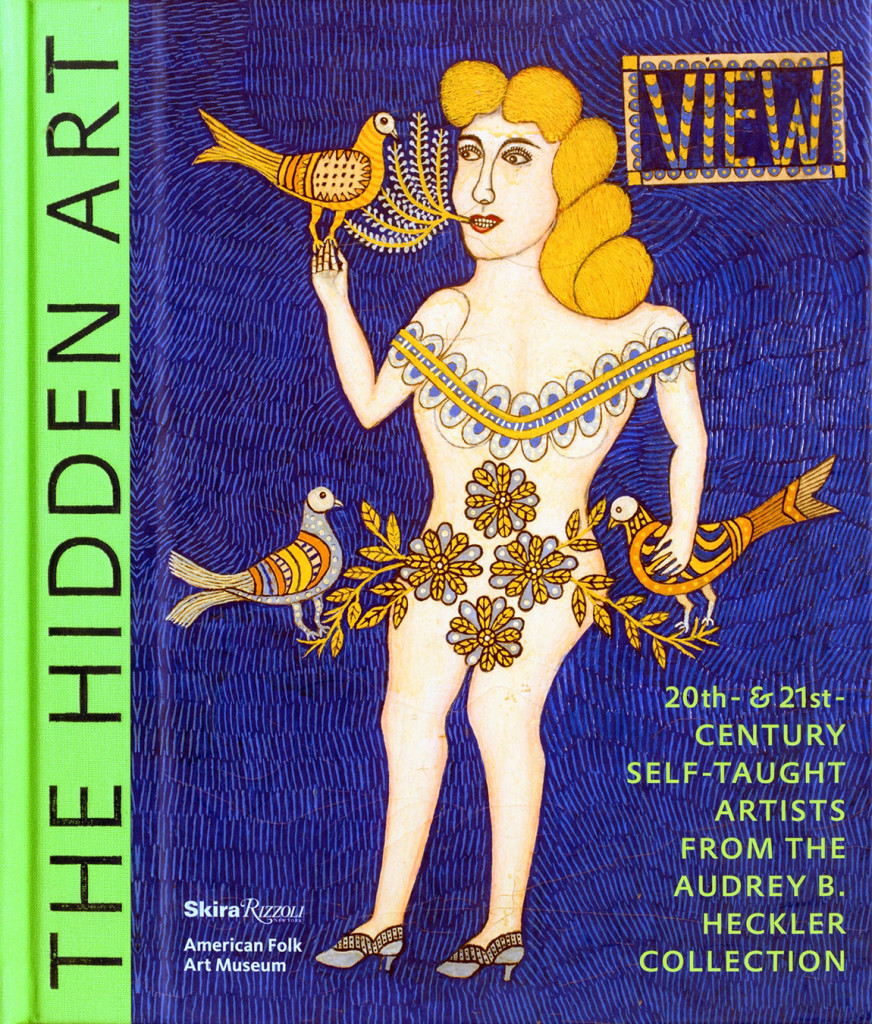

The Hidden Art: 20th- and 21st-Century Self-Taught Artists from the Audrey B. Heckler Collection, by Dr Valérie Rousseau, with Jane Kallir, Dr Anne-Imelda Radice, and other contributors, published by Skira Rizzoli in association with the American Folk Art Museum, www.rizzoliusa.com; 2017; hardcover, 272 pages, $50.

Self-taught art has taken its rightful place in the pantheon of art history. The Hidden Art: 20th- and 21st-Century Self-Taught Artists from the Audrey B. Heckler Collection explores 48 artists who have emerged at the top of their field. Audrey Heckler, the president of the Foundation to Promote Self Taught Art, is recognized as one of the leading collectors of the genre and her collection’s representative tome has put forth an encyclopedic who’s who of the names one must know if they tread into the wild world of art brut: Henry Darger, William Edmondson, Thornton Dial, Madge Gill, Morris Hirschfield, Martín Ramirez, Bill Traylor, Adolf Wölfli and many others.

In her foreword, Valérie Rousseau, curator of self-taught art and art brut at the American Folk Art Museum, writes, “These artworks shed light on the reverse side of history, digging their paths on the margins of a consensual art world. A persistent memory inside cultural images, these creations evolve into game changers and underground players in the extended field of visual art expression.”

Categorized into “Masters,” “Art brut and self-taught artists in Europe,” “American classics,” “Southern self-taught favorites,” and “Twenty-First Century self-taught art worldwide,” the book makes its way through a collection that is as expansive as it is concerned with minute detail. The book includes 205 color illustrations and 32 essays by specialists of self-taught art, who represent the international scope and diversity found in the collection. A must-have compilation for those who appreciate self-taught art and emerging fields of art study. —GS

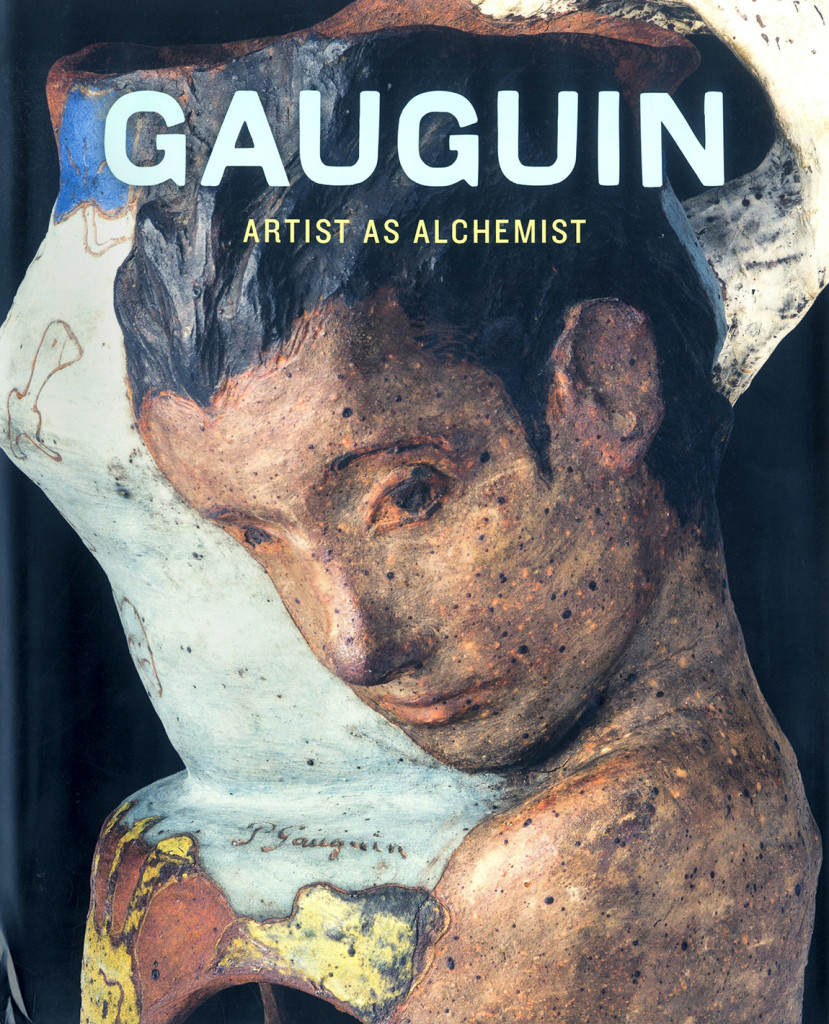

Gauguin: Artist as Alchemist, edited by Gloria Groom with contributions by Gloria Groom, Dario Gamboni, Harriet K. Stratis, Ophélie Ferlier-Bouat, Claire Bernardi, Allison Perelman, Isabelle Cahn, Estelle Bégué, Nadége Horner and Elsa Badie Modiri. Published by the Art Institute of Chicago,www.artic.edu ; distributed by Yale University Press, https://yalebooks.yale.edu; 2017; hardcover, 336 pages, $65.

Paul Gauguin was more than just a painter. That is the powerful message behind the exhibition “Gauguin: Artist as Alchemist” that went on view at the Art Institute of Chicago from June through September, 2017, and which continues at Paris’s Grand Palais through January 21. The exhibition, and its accompanying hardcover text, aim to shed new light on a man who was enthralled with craftsmanship.

Gauguin’s works on view to the public largely focus on paintings. And that is understandable for many obvious reasons. But the lesser-known works that round out his oeuvre were equally fascinating: the ceramics; works on paper, wood and paint; and furniture offer a viewpoint of that artist’s career that is seldom seen. These are the minutiae, the rare, tiny glimpses into Gauguin’s creative spirit that art collector Ambroise Vollard called “little marvels,” or what Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro sarcastically dubbed his “odds and ends.”

In the foreword, we read, “Utilizing extensive new research into Gauguin’s working processes, this project sheds light on his identity as an artist-artisan by focusing on periods of transition and moments when he stood at an artistic crossroad and found new direction by experimenting with unconventional media and methods, leading to breakthroughs that shifted the very definition of art.”

Gauguin, in his own words, claimed that he had a greater skill for craft arts like furniture making or ceramics than for painting. This exhibition and accompanying text are a testament to that. A great read, or even perusal, for those looking to explore a new side of a prolific artist. —GS

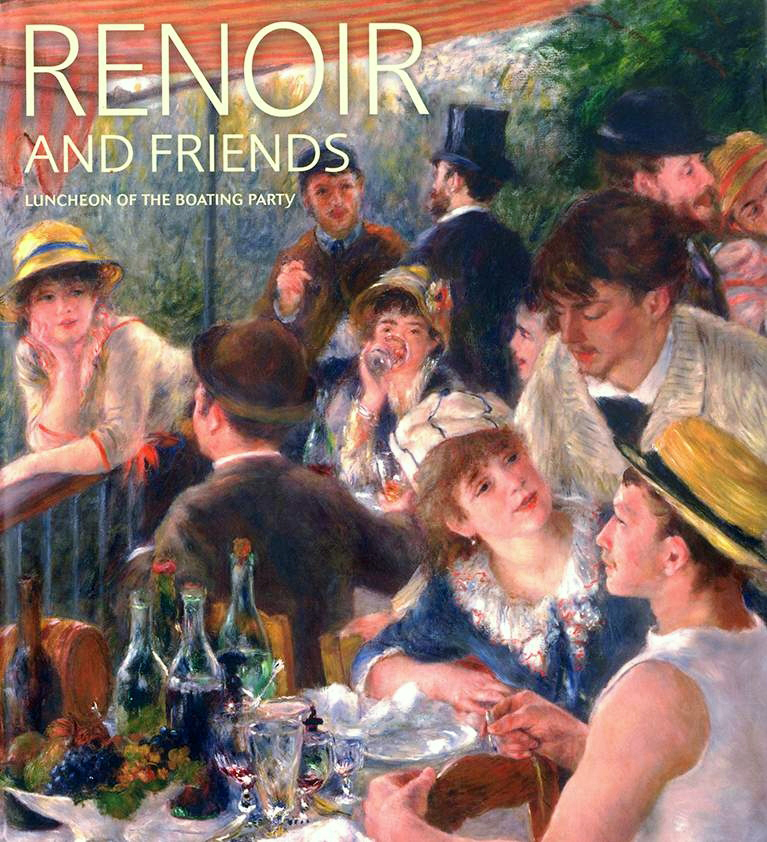

Renoir and Friends: Luncheon of the Boating Party by Eliza E. Rathbone, with contributions by Mary Morton, Sylvie Patry, Aileen Ribeiro, Elizabeth Steele and Sara Tas; 2017, published by Giles Ltd, 32223 Pelican Court, Millsboro, Del., in associations with the Phillips Collection, Washington, DC; 144 pages, 102 color illustrations, hardcover, $34.95

Enjoying much media attention since opening at the Phillips Collection in October, the exhibition “Renoir and Friends” is accompanied by this compelling volume, which is the first of its kind to look in depth at Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s iconic painting “Luncheon of the Boating Party” (1880–81).

Featuring more than 100 color images of works by Renoir and his contemporaries from international museum and private collections, the book is a valuable companion to the Phillips show, which continues until January 7.

Now one of the jewels of the Phillips Collection, Renoir’s “Luncheon of the Boating Party” portrays an informal gathering of real people he knew: fellow artists, journalists, critics, collectors, models and actors. Renoir and Friends deconstructs the painting, revealing the stories behind those he painted and explains his working methods.

Extraordinary details, photographs and contextual works — by Renoir and his contemporaries, including Gustave Caillebotte, Edgar Degas, Léon Bonnat and Édouard Manet — draw out information about who these people were. Essays by leading academics focus on Renoir’s models — including collector Charles Ephrussi and Renoir’s future wife Aline Charigot — and look at how the artist created a painting with universal appeal while remaining convincingly specific.

The setting for this interesting deconstruction by Eliza E. Rathbone, chief curator emerita at the Phillips Collection, and contributors is the balcony of the Maison Fournaise in Chatou overlooking the Seine, where Parisians flocked to rent rowing skiffs, enjoy a meal or stay the night. The restaurant welcomed customers of many classes, including businessmen, society women, artists, actresses, writers, critics, seamstresses and shop girls — all a diverse group that reflected the new, modern Parisian society.

If this particular event depicted in Renoir’s painting never happened, the characters delineated were certainly real, so decoding the invented gathering becomes an entertaining parlor game, and this book serves as a means to examine and better understand the values of French society in the mid- to late Nineteenth Century. —WD