Brooch by Gertrude S. Twichell (1889–1943), early Twentieth Century. Silver, enamel and citrine. Terry and Paul Somerson. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

By Kate Eagen Johnson

BOSTON — Bostonians possess an affinity for jewelry. Think of the Sargent portrait of Isabella Stewart Gardner with her ropes of pearls, Boston’s system of linked parks called the “Emerald Necklace,” and the plastic ball and bat amulet worn by Red Sox right fielder Mookie Betts. So little wonder that the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is mounting “Boston Made: Arts and Crafts Jewelry and Metalwork” from November 17 through March 29, 2020. What might surprise visitors, however, is the caliber of works on display in this scholarly, sumptuous exhibition. These objects represent a superb level of craftmanship, a preference for precious materials and an aesthetic far from the style’s usual austerity as interpreted in the United States. The nearly 100 examples of jewelry, ecclesiastical objects, plaques, boxes, vases and other vessels, clothing and works on paper are bound to dazzle beholders.

This tribute to the interconnected spheres of Arts and Crafts jewelry making and fine metalsmithing is co-curated by Nonie Gadsden, the Katharine Lane Weems Senior Curator of American Decorative Arts and Sculpture of the Americas; Meghan Melvin, the Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf Curator of Design, a curator in the department of prints and drawings; and Emily Stoehrer, the Rita J. Kaplan and Susan B. Kaplan Curator of Jewelry.

The co-curators have mounted the first exhibition solely devoted to Boston-area Arts and Crafts jewelry and art objects of fine metals. As a result of their extensive research, they have restored the artistic reputations of underappreciated artists, many of whom were female, and have reunited “lost” objects with their makers. They made sure to include objects rarely, if ever, exhibited as well as better known exemplars of “the Boston Look.” The co-curators want visitors to understand that jewelry making and fine metalworking were amalgamated pursuits within the Arts and Crafts genre, a view unquestioned at the turn of the Twentieth Century, but one that changed as curators and collectors came to assign jewelry and metals to separate categories.

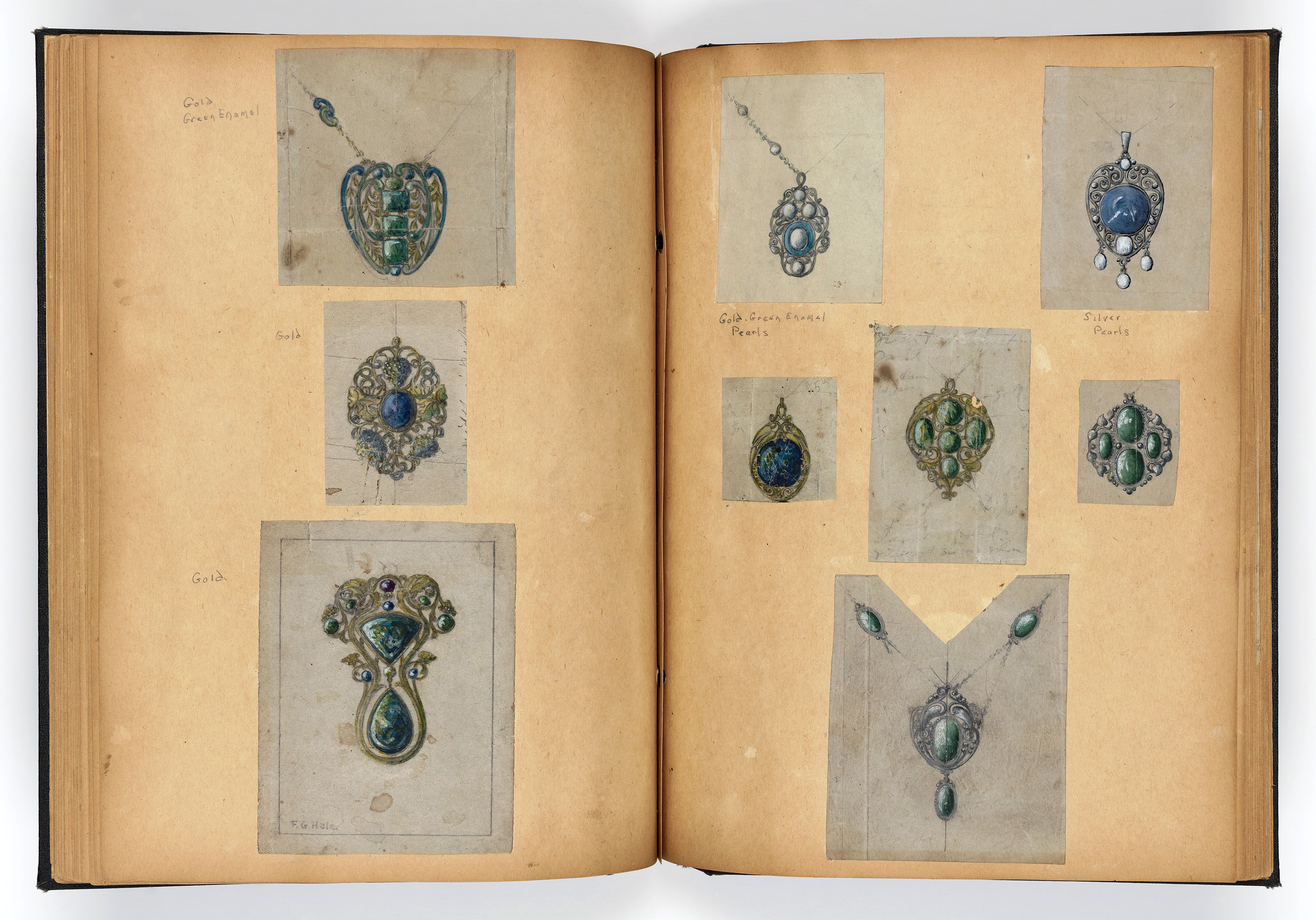

In conversation, Meghan Melvin and Nonie Gadsden pointed to the MFA’s 2014 acquisition of the archive of jewelry maker, fine metalsmith and enamelist Frank Gardner Hale (1876–1945) as the impetus for the exhibition. The MFA procured the trove, which Hale descendants offered for sale through Skinner, with funds donated by Jean S. and Frederic A. Sharf, an anonymous donor, and John Lowell Gardner Fund. Melvin, who proudly identified herself as “the keeper of this wonderful archive,” described the photographs, lecture notes, correspondence and drawings in ink, watercolor and pencil in it. She underscored that the cache supports “the positioning of the MFA as a center of study of jewelry and adornment,” noting that it is the first American art museum to have a curator devoted to jewelry. According to Gadsden, she and the other co-curators realized that “we had a strong collection at the MFA but we knew there was much more to learn and we wanted to dive into it further.”

Make no mistake about it, what the co-curators offer is the crème de la crème of American Arts and Crafts jewelry and fine metal work, objects far more rarified and refined than the stereotypic heavily hammered item of copper or silver perhaps sporting a single stone or a bit of enameling. Consider Margaret Rogers’s knock-out gold, sapphire, diamond and pearl ring regarded as suitable for day wear (cue a “Whoa!”) or Lucretia McMurtrie Bush’s understatedly daring gold, turquoise and pearl brooch. And what objet de vertu of similar era and origin can top Edward Everett Oakes’s masterwork, a box or “casket” of silver and green gold embellished with amethysts, Japanese pearls, Oriental pearls and onyx? Amidst these treasures we are in a realm beyond simple good taste.

The strong artistic and cultural chord tying Boston to England can be seen in objects produced by art metalsmiths who had trained in the national birthplace of the Arts and Crafts movement or who had studied with those who had. Intimately familiar with Anglo-style Arts and Crafts jewelry and metalworking of the highest order, these makers devised kindred custom items for artistic elites.

The strong artistic and cultural chord tying Boston to England can be seen in objects produced by art metalsmiths who had trained in the national birthplace of the Arts and Crafts movement or who had studied with those who had. Intimately familiar with Anglo-style Arts and Crafts jewelry and metalworking of the highest order, these makers devised kindred custom items for artistic elites.

Stressing the significance of Boston as the leader in American Arts and Crafts jewelry design at the time, Gadsden followed that the premier position of this city, long considered a bastion of conservatism in design, surprised commentators even back then. To illustrate her point, Gadsden read aloud Emily E. Graves’s observation from a 1916 issue of the American Magazine of Art that, “curiously enough, it is in once Puritan Boston that there is now the largest number of artist jewelers.”

The life story and artistic impact of Frank Gardner Hale is a major thrust of the exhibition. He studied art in Connecticut and Massachusetts and worked as a graphic artist before moving to England in 1906. There he received additional training in fine metalworking at the Guild of Handicraft at Chipping Campden, and while in England and Scotland fell under the sway of Charles R. Ashbee and Frederick Partridge among other Arts and Crafts master metalsmiths. In 1907 he returned to Boston where he established himself as a jewelry designer and maker. His extraordinary design and execution skills, bolstered by his educational pedigree, propelled him to the forefront of his field. In conjunction with building his business, he assumed leadership roles in Boston’s Society of Arts and Crafts and in the Jewelers’ Guild, took on apprentices, including Edward Everett Oakes, and went on excursions where he combined lecturing on the subject of craft with retailing his jewelry through sales exhibitions akin to trunk shows.

Melvin and Gadsden homed in on some of the exhibition’s most telling objects. Melvin picked a gold, green garnet, sapphire and opal pendant and a related drawing by Hale to convey the idea that jewelers used drawings not only to conceptualize objects but also as a mode of communication with their customers. She explained how Hale sent letters containing multiple sketches of jewelry pieces to his clients, asking them to return those he should execute. The approved design drawings were later assembled in Hale’s scrapbooks.

Melvin also chose a floral brooch by Jessie Ames Dunbar. She told of reading the aforementioned 1916 article “Hand Wrought Jewelry in America” wherein Emily Graves recognized the Boston jewelry maker Jessie Ames Dunbar as producing “work…of special importance.” Melvin was baffled. Who was this notable artist? Research revealed that Dunbar had enjoyed an active career with the Society of Arts and Crafts and that her descendants still held a number of her pieces. Dunbar did not sign her work, so attributions had to be made through other means. The co-curator remarked that Dunbar “was having fun with light and color” when fashioning this brooch of amethyst and tourmalines of different hues. It illustrates her “playful yet deliberate” approach.

Gadsden held up a necklace by Josephine Hartwell Shaw whom she considers “among the leading jewelry makers, male or female.” She characterized this necklace of gold with carved Chinese jade and green glass highlights as expressive of Shaw’s attention to craftsmanship, her experimentation with precious and semiprecious materials, and her skill with design which she learned through art education programs. Indeed, women’s greater access to instruction in metalworking and other arts was a critical factor in Boston’s rise as an Arts and Crafts artisan hub.

![Whiteman (1842–1904) was a painter, designer of book covers, stained glass artist and founding member of the Society of Arts and Crafts in Boston. Fine metalsmiths created chalices, croziers, and other ritual objects for church use. Sarah Wyman Whitman Memorial Chalice by Arthur Stone (1847–1938) and William Blair (active about 1908–1909), designed by R. Clipston Sturgis (1860–1951), 1905. Gold-plated silver, set with jewels (alexandrite chrysoberyl, sapphire, tourmaline, cat’s eye chrysoberyl, citrine quartz, spinel, pyrope garnet, grossular garnet [hessonite], pink sapphire and yellow sapphire). Lent by Trinity Church, Boston. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.](https://www.antiquesandthearts.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/07_Sarah-Wyman-Whitman-Memorial-Chalice-811x1024.jpg)

Whiteman (1842–1904) was a painter, designer of book covers, stained glass artist and founding member of the Society of Arts and Crafts in Boston. Fine metalsmiths created chalices, croziers, and other ritual objects for church use. Sarah Wyman Whitman Memorial Chalice by Arthur Stone (1847–1938) and William Blair (active about 1908–1909), designed by R. Clipston Sturgis (1860–1951), 1905. Gold-plated silver, set with jewels (alexandrite chrysoberyl, sapphire, tourmaline, cat’s eye chrysoberyl, citrine quartz, spinel, pyrope garnet, grossular garnet [hessonite], pink sapphire and yellow sapphire). Lent by Trinity Church, Boston. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Lest metalworking be overlooked, Gadsden then turned to two enameled boxes with bird decoration, one by Laurin Hovey Martin and the other by Frank J. Marshall. She stated that Martin had studied enameling in England with Alexander Fisher, the person credited with reviving the neglected art. Martin brought enameling to the United States, and through his students at the Boston Normal Art School (now the Massachusetts College of Art and Design), the art form spread across the United States. Focusing on Martin’s “phoenix” box, Gadsden drew attention to the quality of its enameling and how the gold foil Martin had applied makes the enamel seem to shimmer. She sees the influence of Martin upon Marshall in the latter’s “peacock” box with “its textured surface and subtlety of colors running into each other.” Gadsden considers Boston the center of enameling in the United States until the 1920s and 1930s when it switched to Cleveland.

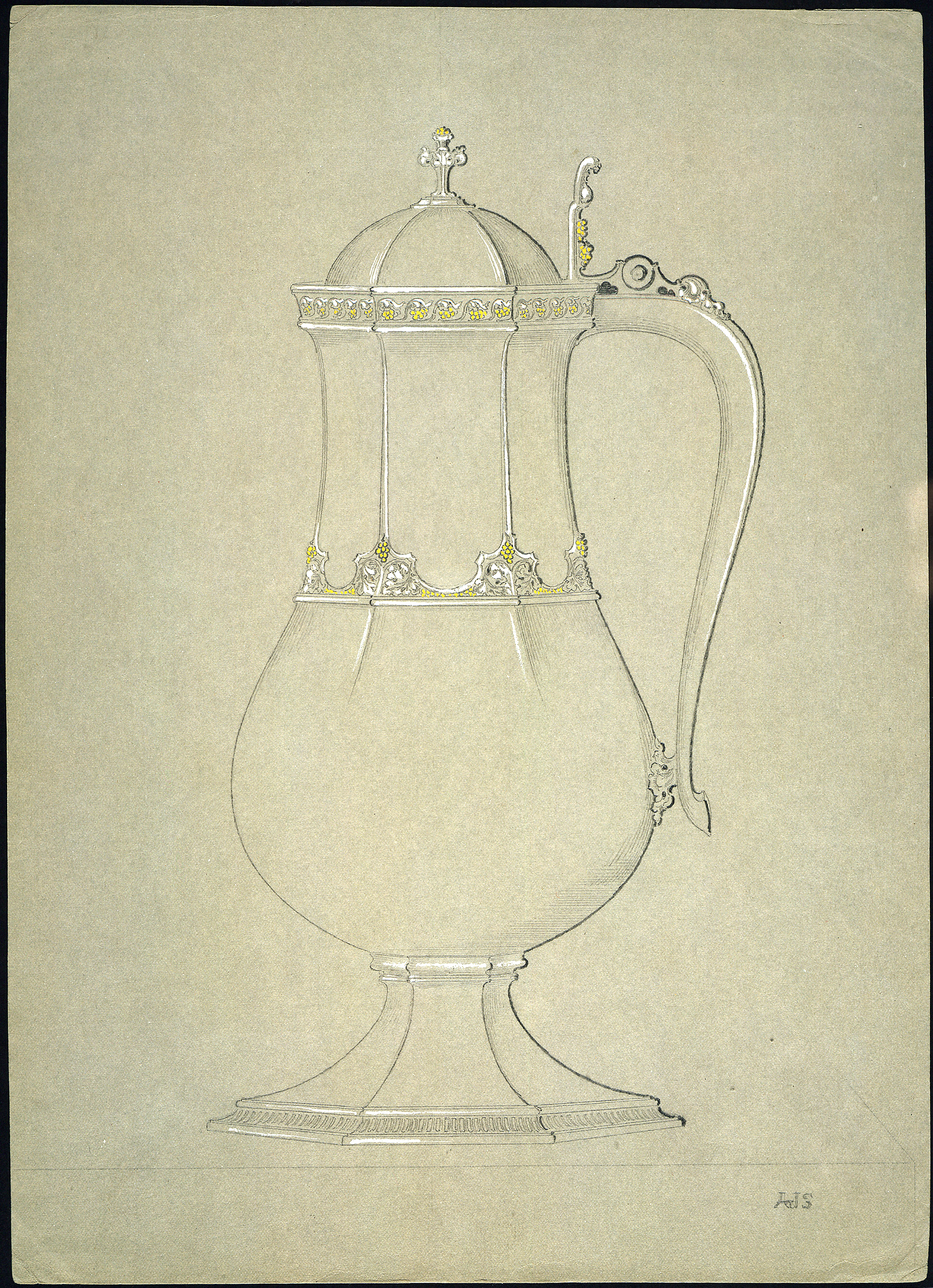

Like gems flanking a central stone, an accompanying publication and a themed installation in the MFA’s permanent galleries enhance “Boston Made.” Arts and Crafts Jewelry in Boston, Frank Gardner Hale and His Circle contains essays by the co-curators as well as biographical profiles and marks of the artists featured. A companion installation of enamels and silver and copper metalwork can be found in the Lorraine and Alan Bressler Gallery for the Arts and Crafts Movement in the Art of the Americas Wing. Gadsden drew special attention to products by English born and trained silversmith Arthur Stone and the early members of the Handicraft Shop.

The MFA’s stellar “Boston Made” is part of a thematic collaborative titled “Mass Fashion: Past, Present and Future” involving cultural institutions in the Commonwealth. Currently on view are “Head to Toe: Hat and Shoe Fashions from Historic New England” shown at the Eustis Estate in Milton until February 24; “Leisure Pursuits, The Fashion and Culture of Recreation” running at Fruitlands Museum in Harvard through March 24; “Fashioning the New England Family” featured at Boston’s Massachusetts Historical Society until March 29; and “Uneasy Beauty: Discomfort in Contemporary Adornment” mounted by the Fuller Craft Museum in Brockton through April 21.

In summary: “Boston Made: Arts and Crafts Jewelry and Metalwork” will run from November 17 through March 29, 2020. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is at the Avenue of the Arts, 465 Huntington Avenue. For more information, www.mfa.org or 617-267-9300.

Nonie Gadsden, Meghan Melvin and Emily Stoehrer authored the accompanying publication, Arts and Crafts Jewelry in Boston, Frank Gardner Hale and His Circle. It will be issued by Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in November.

For information about the “Mass Fashion: Past, Present and Future” collaborative, see www.massfashion.org/about.

Kate Eagen Johnson is an expert in American decorative arts and an independent museum consultant, historian, lecturer and author.