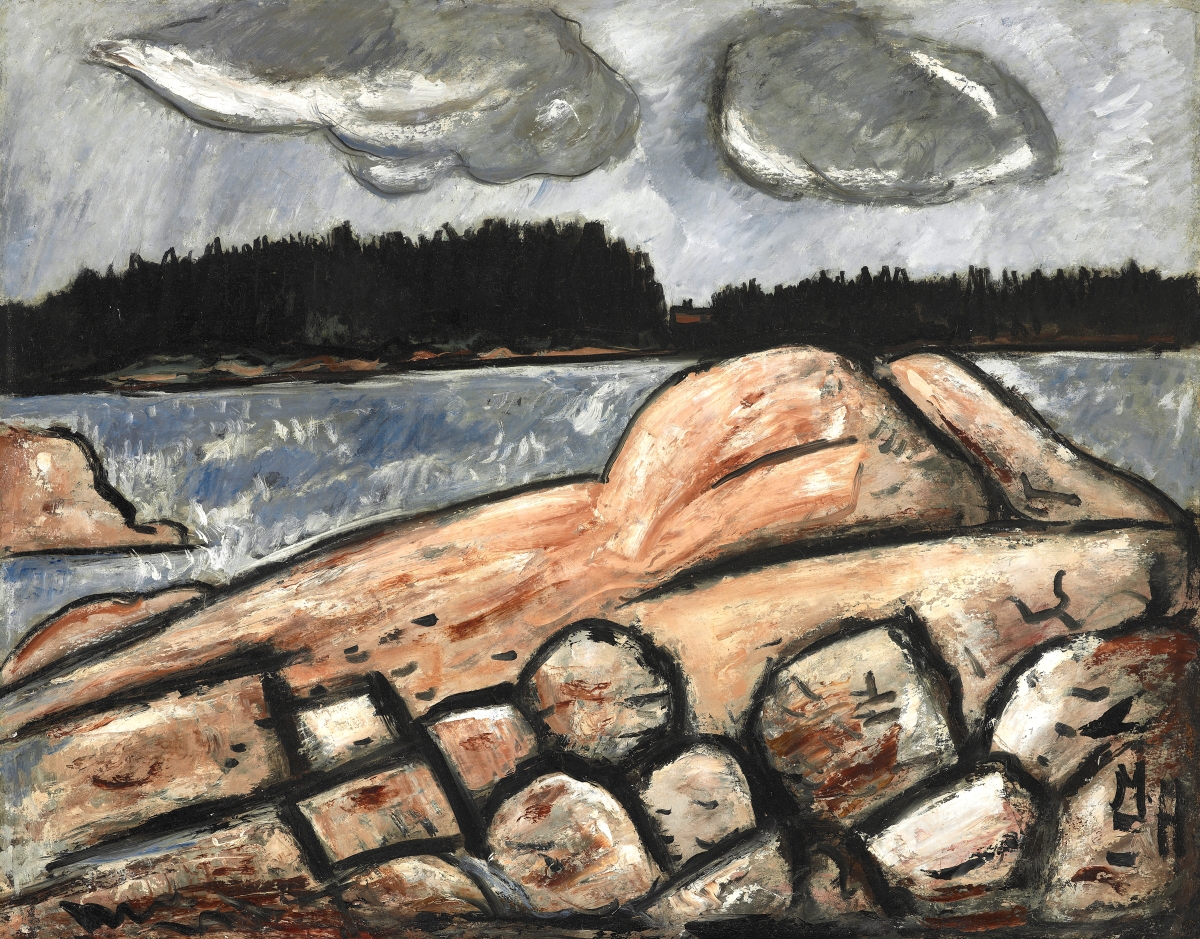

“After the Storm, Vinalhaven” by Marsden Hartley (American, 1877-1943) 1938-39, oil on Academy board. Gift of Mrs Charles Phillip Kuntz, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine.

By Kristin Nord

BRUNSWICK, MAINE – Most of us in our lifetimes, if we are lucky, find a place that becomes our spiritual True North. For many artists over two centuries that place has been Maine.

Whether landing as a student or as an adult seeking relief from hot summers and urban centers, artists have made their way here, to study or to find refuge, and many, to set down part-time roots and establish studios. The fierce beauty of this place, with its ocean light, turbulent seas and rocky outcroppings, feature prominently as subject matter. There are its lumberjacks, fishers, shipbuilders and potato farmers. And one senses in the art that has been made in Maine the fundamental question: How does this special place inform character?

“At First Light: Two Centuries of Artists in Maine,” on view at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art (BCMA) through November 6, offers visitors considerable food for thought in 100 works across media drawn largely from BCMA’s extensive collection.

The show had been scheduled originally to run during Maine’s bicentennial observances in 2020, but a two-year delay, in response to Covid-19 closures, enabled the co-curators, Anne Collins Goodyear and Frank H. Goodyear III, to expand upon their original vision. And the Goodyears, who are also the museum’s co-directors, took obvious delight adding two tangential exhibitions as well as securing significant loans from the Addison Gallery of American Art, the Farnsworth Art Museum, the Harvard Art Museum, the Rhode Island School of Design Museum and the Toledo Museum of Art. Since its founding as one of the earliest college art museums, BCMA has grown and significantly diversified its collection in recent years.

“Abraham Hanson” by Jeremiah Pearson Hardy (American, 1800-1887), circa 1828, oil on canvas. Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Mass. / Art Resource, New York City.

When Maine became the 23rd state admitted to the Union in 1820, it entered as a free state during a time when there were roiling debates over the institution of slavery. In its early years Maine grew dramatically: doubling its population in the first 30 years after statehood and establishing a wide variety of maritime and inland enterprises.

“At First Light” unfolds chronologically, with early landscape paintings by Charles Codman (1800-1842), Jonathan Fisher (1768-1847), and Thomas Cole (1801-1848). A drawing of a Machiasport petroglyph, completed in 1868-69 by Henry Robert Taylor, a civil engineer, and reproduced in the Smithsonian Institution’s 1888 Bureau of American Ethnology report, offers evidence that the Indigenous pictorial images in this part of the state date back some 3,000 years.

Among Maine’s early proselytizers was Winslow Homer (1836-1910), who settled permanently in Prouts Neck in 1884 and created his most celebrated paintings and watercolors here. Rockwell Kent (1882-1971) arrived in 1905 on Monhegan Island, and over the next five years painted landscapes in all seasons. George W. Bellows (1882-1925) first encountered Monhegan Island in 1911 and found it “endless in its wonderful variety (and) possessed of enough beauty to supply a continent.” Frank Weston Benson (1862-1951), who had first visited Maine in 1901, served up this field report: “From the moment we saw it, North Haven felt like home.” Benson would return to North Haven every summer for the rest of his life. Then there was John Marin (1870-1953), who began a lifelong association with Maine, describing the wild and unforgiving shoreline as “fierce, relentless, cruel, beautiful, hellish,” and so captivating that he would return to it each summer until his death.

As early as 1900, tourism had emerged as an industry; by 1913, the State of Maine was providing overnight rail service with Pullman sleeper cars between Grand Central Terminal in New York City and Portland, with some sleepers continuing to Bangor.

“North” by William Wegman (American, b 1943), 2001, pigment print on paper. Gift of William Wegman and Christine Burgin, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine. Courtesy of the artist.

Art colonies sprouted in Ogunquit and Georgetown, Monhegan, Skowhegan, Mount Desert Island, Vinalhaven and the Rangely Lakes. With the establishment of arts schools, such as the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture in 1946 and the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in 1950, new museums and galleries in Ogunquit, Rockland, Waterville, Bangor, Lewiston and Monhegan came into being. Today, according to recent figures provided by the Americans for the Arts Action Fund, an estimated 1,500 artists live and work in Maine, and the arts and culture sector contributes $1.6 billion annually to Maine’s economy.

For three generations, for the Wyeths of Chadds Ford, Penn., the Pine Tree State has loomed as a seasonal lure. Artists Eliot (1901-1990) and Fairfield Porter (1907-1975) of the Porter family of Winnetka, Ill., summered on Great Spruce Head in the home their father had built in 1913; Fairfield once reported matter-of-factly, “We go to Maine in the summer because I have since I was six. It is my home more than any other place. I belong there.”

Much as the Wyeths drew inspiration from Port Clyde and its islands nearby, Lois Dodd (b 1927) has zeroed in on her property in Cushing. “I work best going back to the same places. I change, they change, or the weather changes. I used to think the subject would dry up and I would need to move. But that never happened.”

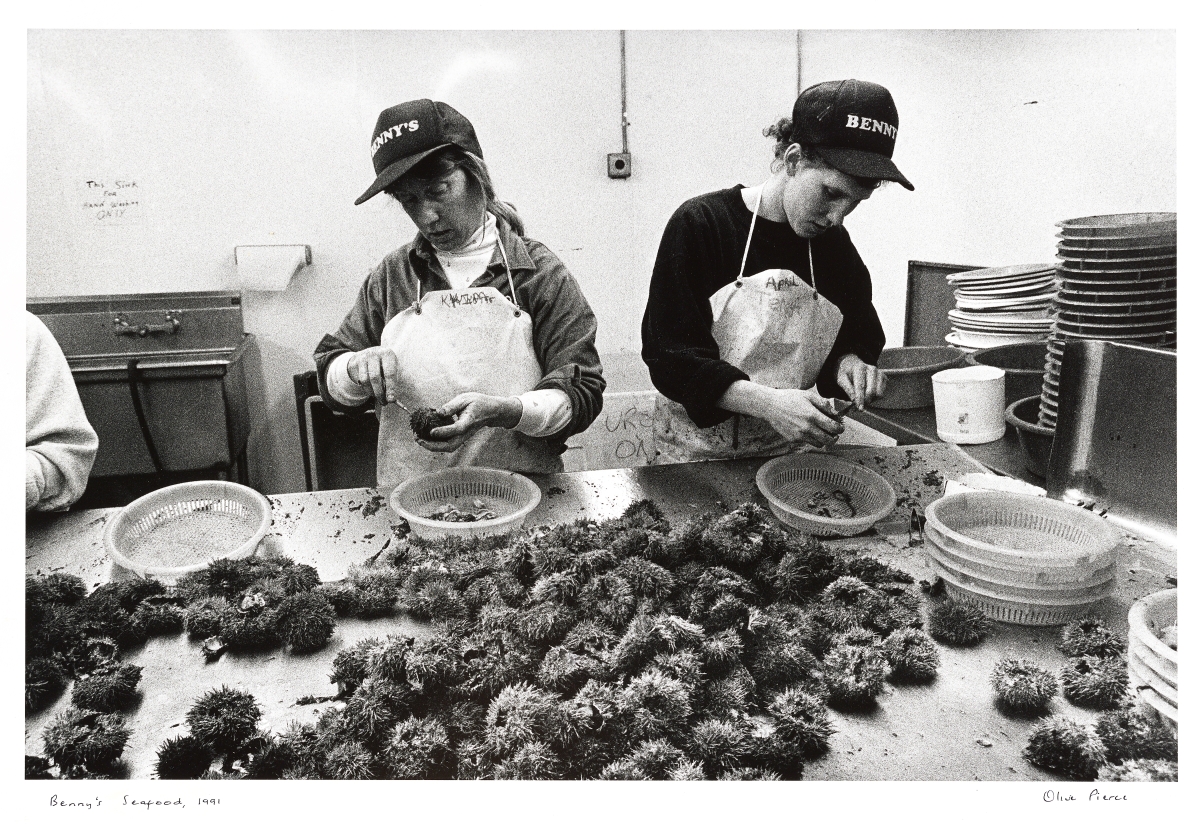

The documentary photographer Berenice Abbott (1898-1991) first visited Maine in the 1950s and settled six years later in an abandoned inn in the middle of the state. Her book of photographs, A Portrait of Maine appeared as an homage to the state’s labor history when it was published in 1968. And her student, Olive Pierce (1925-2016) took a leaf from her book by documenting the lives of two fishing families in Up River: The Story of a Maine Fishing Village (1996).

“Benny’s Seafood” from the portfolio Up River: The Story of a Maine Fishing Community by Olive Pierce, (American, 1925-2016) 1991, gelatin silver print. Gift of the photographer, Olive Pierce, Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine. ©Olive Pierce, all rights reserved.

Carl Sprinchorn (1887-1971) took to heart his teacher’s challenge to chronicle the forces that were shaping modern life. Lumberjacks, and river drivers became his focus for some 40 years, and his paintings earned him kudos from Marsden Hartley (1877-1943) for their verisimilitude.

After the Second World War, Maine became known for its support of emerging artists of color. From 1947 to 1974, through a collaboration between Skowhegan College of Painting and Sculpture and Howard University, some 30 students were accepted for its summer sessions, most on full scholarships.

Romare Beardon (1911-1988), Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012), Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000), David Driskell (1931-2022) and Ashley Bryan (1923-2022) all studied there; Driskell became widely revered as a teacher and for his success in establishing African American art as an academic discipline. Driskell built his home and studio in Falmouth and worked in watercolor, gouache, collage and more. Bryan, who chaired the Dartmouth College art program until 1988, became renowned for his award-winning children’s books rooted in African folk tales and African American spirituals. In his studio on Cranberry Island, Bryan worked in a broad range of media – glass, paper collage, oil, tempera and made woodblock prints and puppets crafted from driftwood and sea glass.

The school served as a catalyst for other artists as well. “At Skowhegan I tried plein air painting and found my subject matter and a reason to devote my life to painting,” Alex Katz later said. He ultimately set down roots in Lincolnville, where a nearby beach, ferry terminal and lobster pound, and the arrival of friends and family – became continual sources of inspiration.

Flower-top Basket by Molly Neptune Parker (Passamaquoddy and American, 1939-2020), 2019-20, ash and sweetgrass. Courtesy of the Hudson Museum, University of Maine, Orono.

Two tangential exhibitions cap the survey; the first, “Innovation and Resilience Across Three Generations of Wabanaki Basket-Making,” looks at the evolution of this Indigenous art form as it became an economic tool following European colonization. Artists, including the late Molly Neptune Parker (1959-2022), and her grandchild, Geo (b 1988), elevated the craft to fine art with exquisite baskets that displayed their virtuosity. This has been curated by members of Bowdoin’s Native American Students Association, with wall text translated by a member of the Passamaquoddy nation. Sadly, with the arrival of the emerald ash borer in Maine, this sacred art form is threatened. A special task force is working to preserve seed and explore alternatives to brown ash, the craft’s primary material.

Another exhibition showcases images by the architectural photographer Walter Smalling Jr of the homes and studios of 26 prominent Maine artists. Smalling’s photographs are drawn from At First Light: Two Centuries of Maine Artists, Their Homes and Studios, published in 2020 by Rizzoli Electa, with accompanying text from the Goodyears and Michael K. Komanecky, the Farnsworth’s chief curator.

In recent years, Maine artists have addressed many of the serious issues of the day. The photographer John McKee’s (b 1936) series, “As Maine Goes,” became a political battle cry in 1966 with its juxtaposed images of Maine’s natural beauty and its degradation of its resources. Daniel Mintner’s (b 1961) mixed media collage, “A Distant Holla from the Mouth of New River,” 2020, speaks to the 1911 forced removal of the residents of a racially diverse fishing village near Phippsburg. Katherine Bradford’s (b 1942) “Fear of Dark,” which she completed in the summer of 2020, is a poignant address to our collective need for healing.

“What does it mean to be a Maine artist today?” Bowdoin’s co-curators ask. From their Northerly perch, they note, Maine artists continue to have the advantage of feeling “simultaneously connected and distant from urban art centers.” To their mind, Maine remains a place for artists “who dare to depart from tradition.”

“At First Light: Two Centuries of Artists in Maine” is on view through November 6.

Bowdoin College Museum of Art is at 245 Maine Street. For further information, 207-725-3575 or www.bowdoin.edu/art-museum.