“Thunderbird Transformation Mask” by a ‘Namgis Kwakwaka’wakw artist, Nineteenth Century, cedar, pigment, leather, nails, metal plate. Brooklyn Museum; Museum Expedition 1908, Museum Collection Fund, 08.491.8902.

By Madelia Hickman Ring

BROOKLYN, N.Y. — The Brooklyn Museum of Art opened in 1824 and has planned a rolling slate of celebratory events to celebrate its 200th anniversary. Festivities kicked off in early October, when the museum — the second largest in New York City after the Metropolitan Museum of Art — opened “Toward Joy: New Frameworks for American Art.” The exhibition — billed by the museum as a transformative reinstallation of its American Art galleries — highlights more than 400 works spanning two millennia, including more than 120 works not previously exhibited.

The bicentennial milestone was not the sole reason for the rehang, as explained by Catherine Futter, the museum’s director of curatorial affairs and senior curator of decorative arts, and Liz St George, assistant curator of decorative arts at the museum.

“We felt the need to address the idea of what encompasses American art, how we want to define it, and what stories we want to tell, especially in these complex times. With a new curatorial team in place, we welcomed new perspectives that pushed us to reassess methodologies and representation within our collection.

“Many of the most iconic works from the Brooklyn Museum’s collection are on view in ‘Toward Joy,’ but in very new contexts. Many typical American art installations focus on time, culture, style or geography. Our new installation takes a different approach in putting forward Black feminist and Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) perspectives, emphasized through distinct curatorial frameworks that bring together works from different cultural origins, geographical locations, time periods and materials.”

“Diana of the Tower” by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1895, gilded bronze. Brooklyn Museum, Robert B. Woodward Memorial Fund, 23.255.

As the curatorial team developed “Toward Joy,” they were acutely conscious of the many cultures and communities the museum serves and were careful to recognize the necessity of deviating from a white-centric art historical narrative to tell more inclusive stories. To fully realize that, they had conversations with thought partners and advisory committees, including the Black Feminist Roundtable, a committee made up of 15 artists, scholars, curators and writers that met regularly to guide the exhibition’s development.

One facet of the exhibition has a floral theme and is titled “To Give Flowers.” Within it, visitors might see still life paintings, Laura Wheeler Waring’s “Woman with a Bouquet” and a Herter Brothers chest of drawers with floral decoration. The chest, once featured in the museum’s previous decorative arts gallery, now has new neighbors, including an 1853 Cornelius & Baker candelabrum and Eero Saarinen’s Tulip chair.

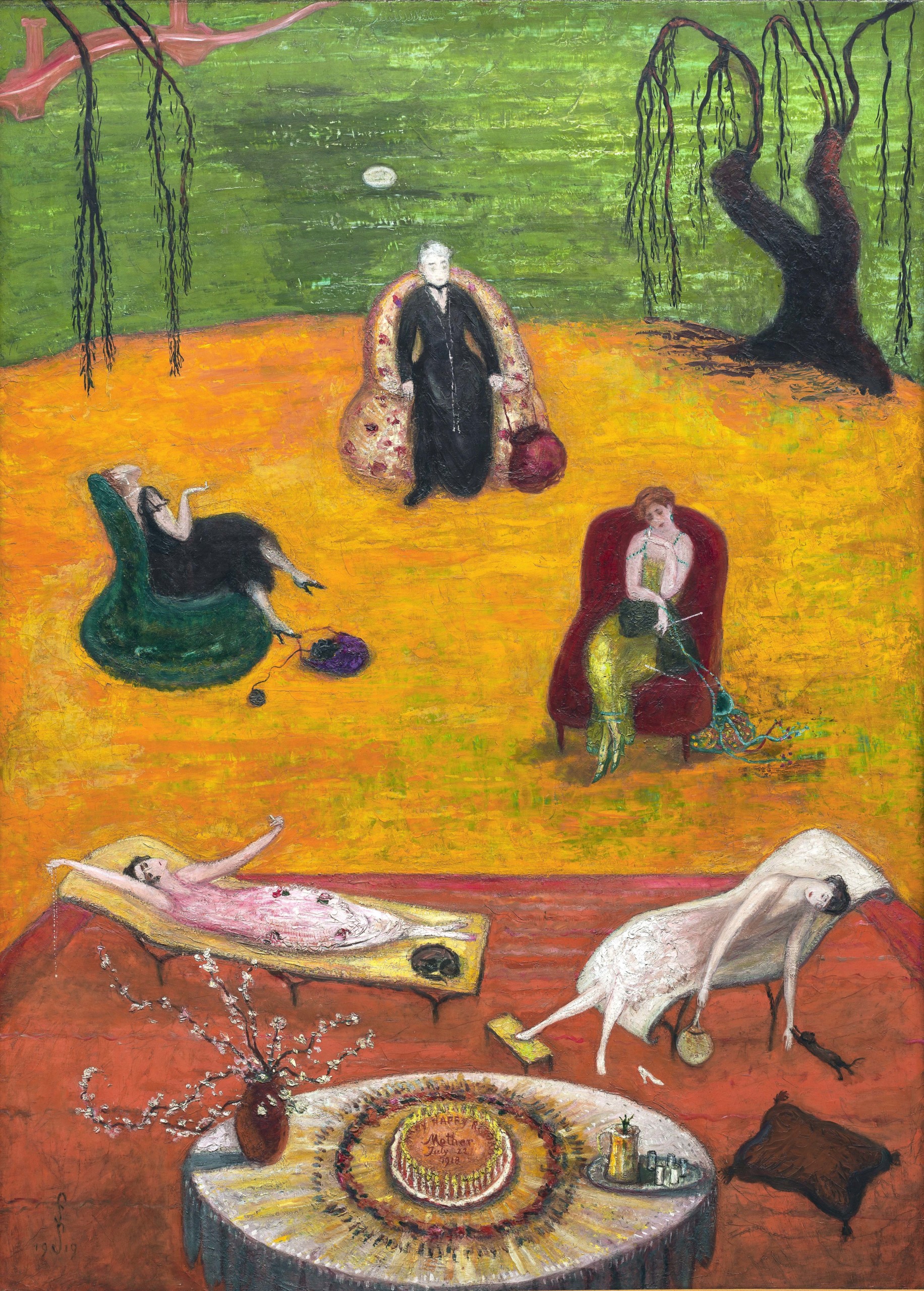

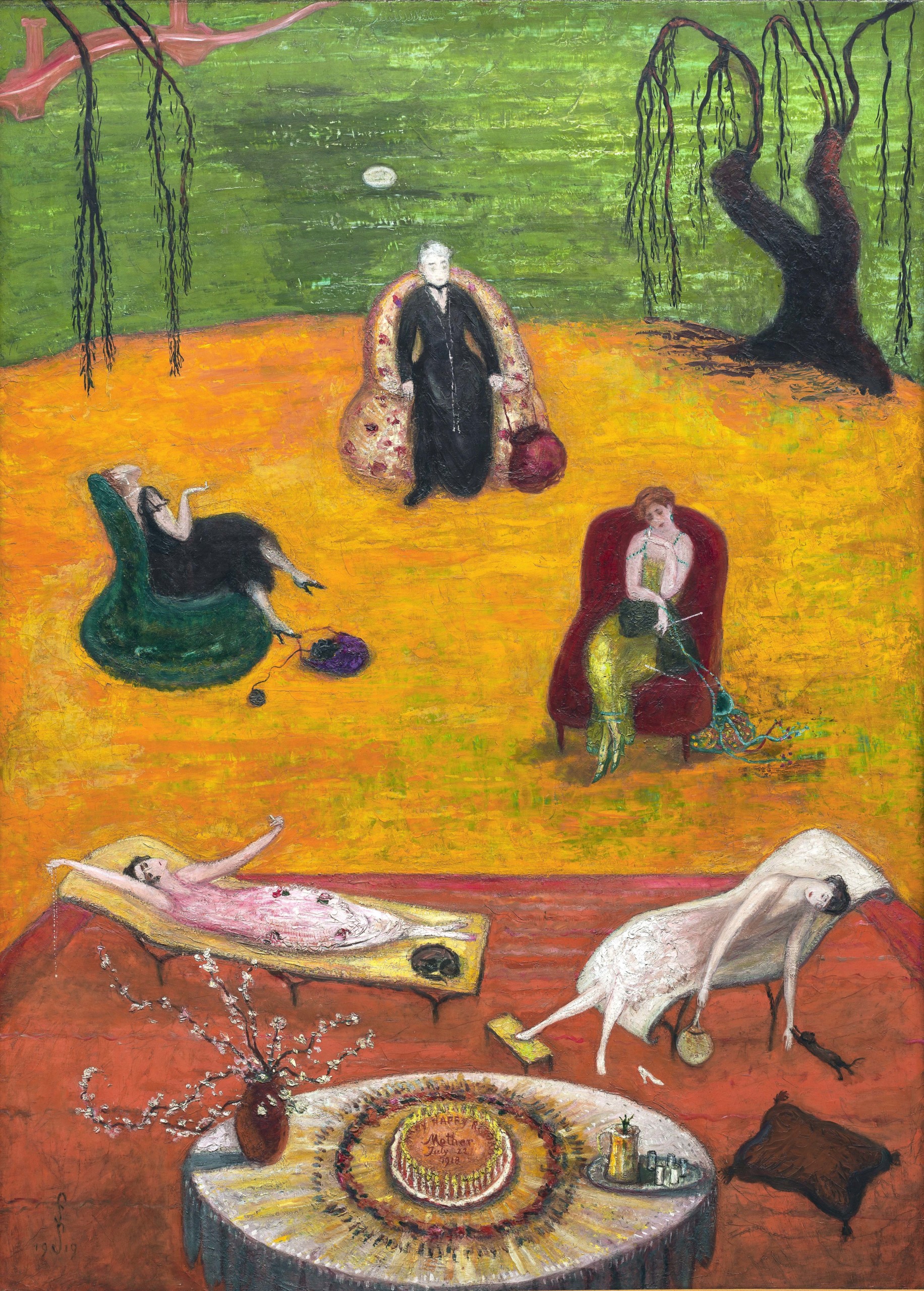

In “A Quiet Place,” visitors are encouraged to explore stillness as a means of repose and resistance. Here, objects from the museum’s American art, Indigenous and arts of Americas collections are installed alongside decorative arts. The warmth and comfort of a domestic space are recalled with candlesticks by Marion Noyes (circa 1955) and Marie Zimmermann (1921-1925) sharing space with the circa 1881 Herter Brothers-designed mantel from the Sloane-Griswold House. Serene landscapes, including “Sunrise” by George Inness (1887) and Arthur B. Davies’ “Every Saturday” are in dialogue with the vividly-colored “Heat,” Florine Stettheimer’s 1919 composition and Native figures from North and Central America.

“Heat” by Florine Stettheimer, 1919, oil on canvas. Brooklyn Museum; Gift of the Estate of Ettie Stettheimer, 57.125.

“Trouble the Water” not only celebrates African American spirituals and explores the link between water and notions of freedom, life and spirituality but promotes the exhibition’s primary narrative to center Black feminist and BIPOC intellectual and creative contributions to the history of art and culture. Matthew Daly’s goldfish-decorated Rookwood vase (1893) carries the theme well, as does Frederick Waugh’s “The Great Deep.” The museum creates an interesting dialogue between two vessels made to carry water: a double-spouted pottery example made by an unknown Nasca artist in Palpa, Peru, 150-300 CE, and a water filter made by Union Pottery Works in the late Nineteenth Century.

Thought-provoking juxtapositions are present throughout the exhibition. In “Surface Tension,” the nude figure is celebrated in the tactile and glistening surface of a Beatrice Wood chalice (circa 1975), next to Laura Aguilar’s nude self-portrait (1996) conjures the ideas of women’s creative agency and power. Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ “Diana of the Tower,” a long-standing museum favorite, makes a cameo appearance in this section and invites comparisons to Gaston Lachaise’s “Standing Woman.”

The “Several Seats” floor-to-ceiling installation of chairs from the Eighteenth Century to the present day raises questions about their makers and explores concepts of value through the themes of materials, labor, emotional resonance and marketing. Facing the chairs are colonial portraits of white sitters, hung at eye-level to give viewers the ability to look the subjects gaze and challenge the prominence the art historical canon gives to portraiture. Here, visitors will see works ranging from Joshua Johnson’s triple portrait “John Jacob Anderson and Sons, John and Edward” to “One Family House Chair,” Kate Loye’s mixed media chair from 1986.

“One Family House Chair” by Kate Loye, designed 1984, manufactured 1986, steel tubing, electrostatic paint, Astroturf, plywood. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Riane Eisler, 86.240.

“This particular installation dispels the idea that traditional modes of scholarship, particularly connoisseurship, sit in tension with social and cultural history frameworks that emphasize a social justice mission,” noted the curators. “Visitors may not read all the labels, but they will look and consider an object’s formal characteristics in connection to big-picture themes, spurring unexpected observations and exciting discoveries.”

“The galleries are breaking new ground in many ways,” the curators share, “from the celebration of Black joy to its presentation deeply informed by the suppression of BIPOC people’s voices and labor throughout time.”

Consideration of violence against and the romanticism of Indigenous cultures is particularly encouraged in the “Radical Care” gallery. It features a structure, the American Art Study, purposely built for the installation that was designed so objects could be examined. There, visitors can study a ceramic tripod bowl, made in Peten, Guatemala, 400-500, by an unknown Mayan artist, Robert Seldon Duncanson’s copy of Thomas Cole’s “Dream of Arcadia” and a color woodcut of El Capitan by Chiura Obata.

The 1965 exhibition, “First Group Showing: Works in Black & White” inspired the section titled “Counterparts,” in which, among other things, Malvina Hoffman’s “Martinique Woman” invites a dialogue with a black and white photograph of a sponge vendor by Graciela Iturbide (1974).

Installation view of “Counterparts,” in “Toward Joy: New Frameworks for American Art,” Brooklyn Museum. Thomas Barrett photo.

The final section, titled “Witness,” exploits the museum’s broad and deep holdings of portraits but goes further, inviting comparison to pieces representing civic engagement and community service. Where else would Rembrandt Peale’s 1826 portrait titled “The Sisters (Eleanor and Rosalba Peale)” communicate with a sculptural “Thunderbird Transformation Mask,” made by a ‘Namgis Kwakwaka’wakw artist.

“We were excited to ask new research questions guided by these specific frameworks,” concluded the curators, who noted that creating the exhibition “was a reaffirmation of the ability of decorative arts to tell remarkable stories of the past that project our current societal values. It is a remarkably flexible field where research and connoisseurship can illuminate themes and narratives that are relevant to modern times. While many of the objects in the galleries were made for elite consumers, by shifting perspectives and asking new questions — in this case, informed by Black feminist frameworks — a broader view of society can emerge that introduces exciting new perspectives on race, class, gender and the interconnectedness of cultures around the globe.”

The Brooklyn Museum of Art is at 200 Eastern Parkway. For information, 718-638-5000 or www.brooklynmuseum.org.