Earning $72,000 and the highest price of the sale, this platinum and diamond ring had a 5.23-carat blue Kashmir sapphire. Gemological reports that accompanied it certified that the sapphire showed no signs of having been heat-treated.

Review & Onsite Photos by Rick Russack

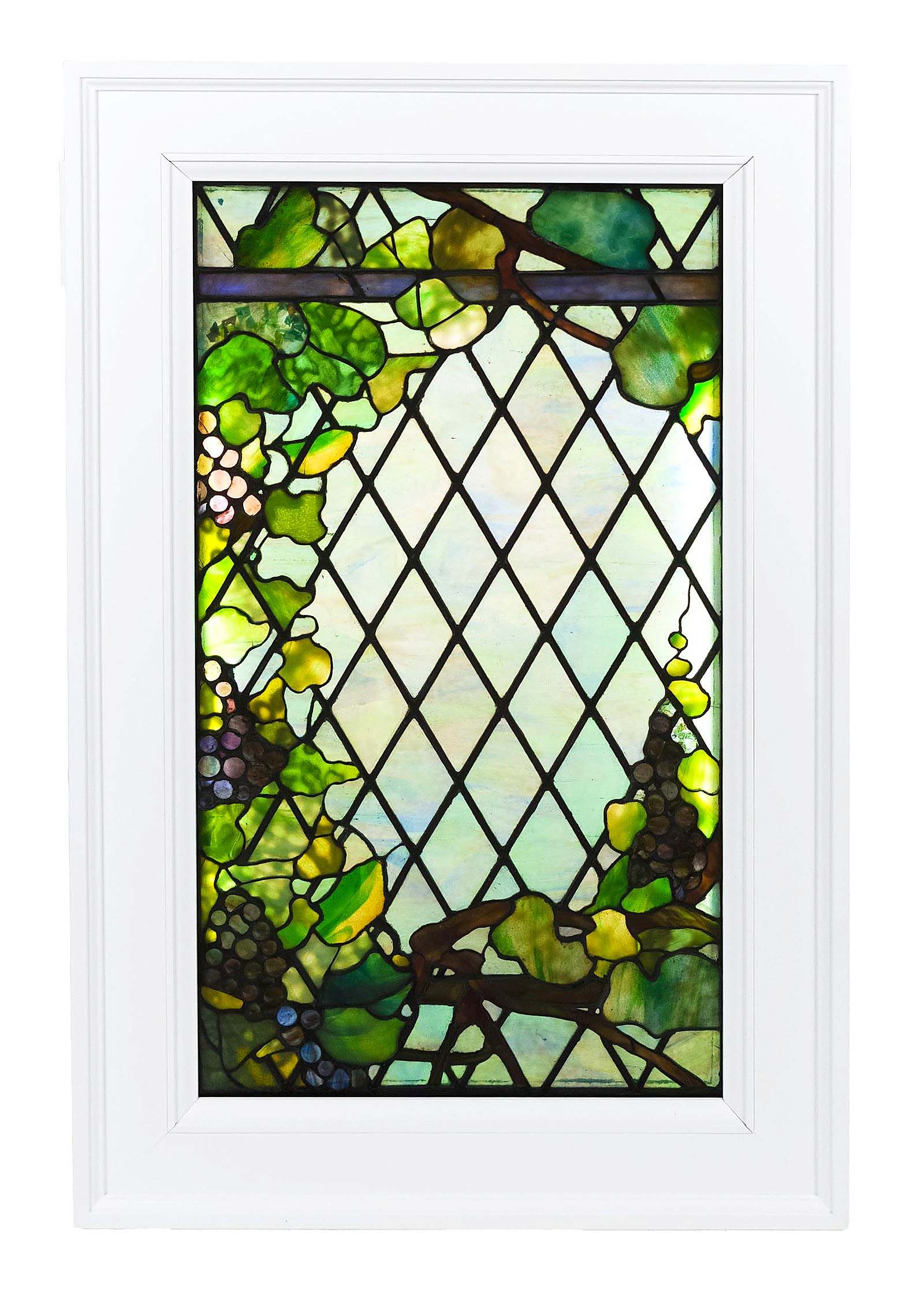

PLAINFIELD, N.H. — What do a Kashmir sapphire and diamond ring, a 2011 Corvette, a Tiffany stained glass window and a very small Eighteenth Century Queen Anne dropleaf table have in common? On the surface, perhaps not much, but each of those items was among the top four highest priced lots at William A. “Bill” Smith’s $992,200 post-Memorial Day auction that took place on May 29. Go a little deeper into the stars of the day and you’ll find a signed Dunlap highboy, a carved Seventeenth Century blue-green desk box from the Jerrilee Cain collection of Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century American, English and European furniture and accessories. You’d also find a silver casting of Frederic Remington’s (American, 1861-1909) “The Outlaw” and a pair of bronze dogs by Jonathan Wylder (British, b 1957).

Topping the day by earning $72,000 was the diamond ring with a 5.23-carat blue Kashmir sapphire. It was accompanied by four certificates stating that the stone had not been heat-treated and the platinum setting included several diamonds. It was part of a strong selection of jewelry, which also included an 18K gold Nicolis Cola lariat necklace, with ball and tassel ends, that sold for $13,200. It contained 200 grams of gold and was 40 inches long. Another necklace popular with bidders was a stamped 14K white gold, graduated diamond riviera necklace set with approximately 16 carats of round brilliant cut diamonds of H-I color and SI-I1 clarity; it realized $8,400.

The American furniture market appeared strong, with four pieces achieving prices in excess of $10,000 and several other pieces meeting or exceeding expectations. Earning $33,000 was a circa 1760 Queen Anne oval dropleaf table that was exceptionally small, measuring slightly more than 25 inches tall and less than 31 inches long. The maple table had swing-leg leaf supports and was cataloged as having a later black painted surface. When the leaves were dropped, it measured just 9½ inches; with the leaves raised, it spanned 29 inches.

During the sale, a little more information was provided about this Dunlap highboy. Furniture scholar Phil Zea, sitting in the audience, confirmed the signature of Samuel Dunlap’s apprentice Joslin. The 1770-90 highboy sold for $20,040.

Earning $20,400 was a circa 1770-90 two-part maple highboy, cataloged as “Dunlap workshop” and “possibly” signed Joslin. As he was selling it, Smith provided additional information saying that it was definitely signed on a drawer back, though it had to be held in a certain way to be legible. Phil Zea, president emeritus of Historic Deerfield and co-author with Donald Dunlap and John A. Nelson of The Dunlap Cabinetmakers: A Tradition in Craftsmanship (Stackpole Books, 2007), was seated in the audience. From the podium, Smith asked Zea which member of the Dunlap family Joslin had been apprenticed to and Zea responded, “Samuel.” The highboy had its original hardware and the characteristic Dunlap carved and scrolled apron.

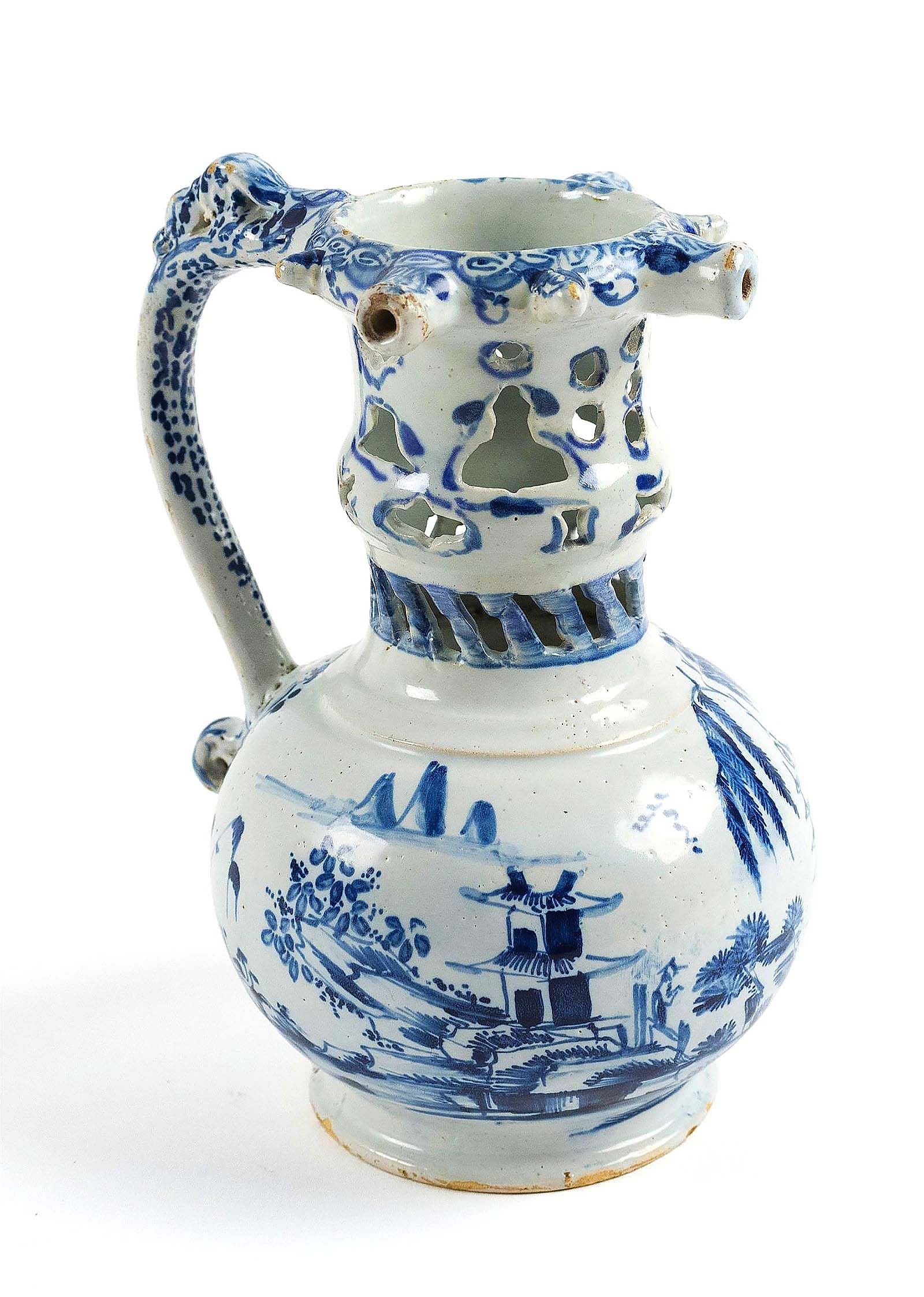

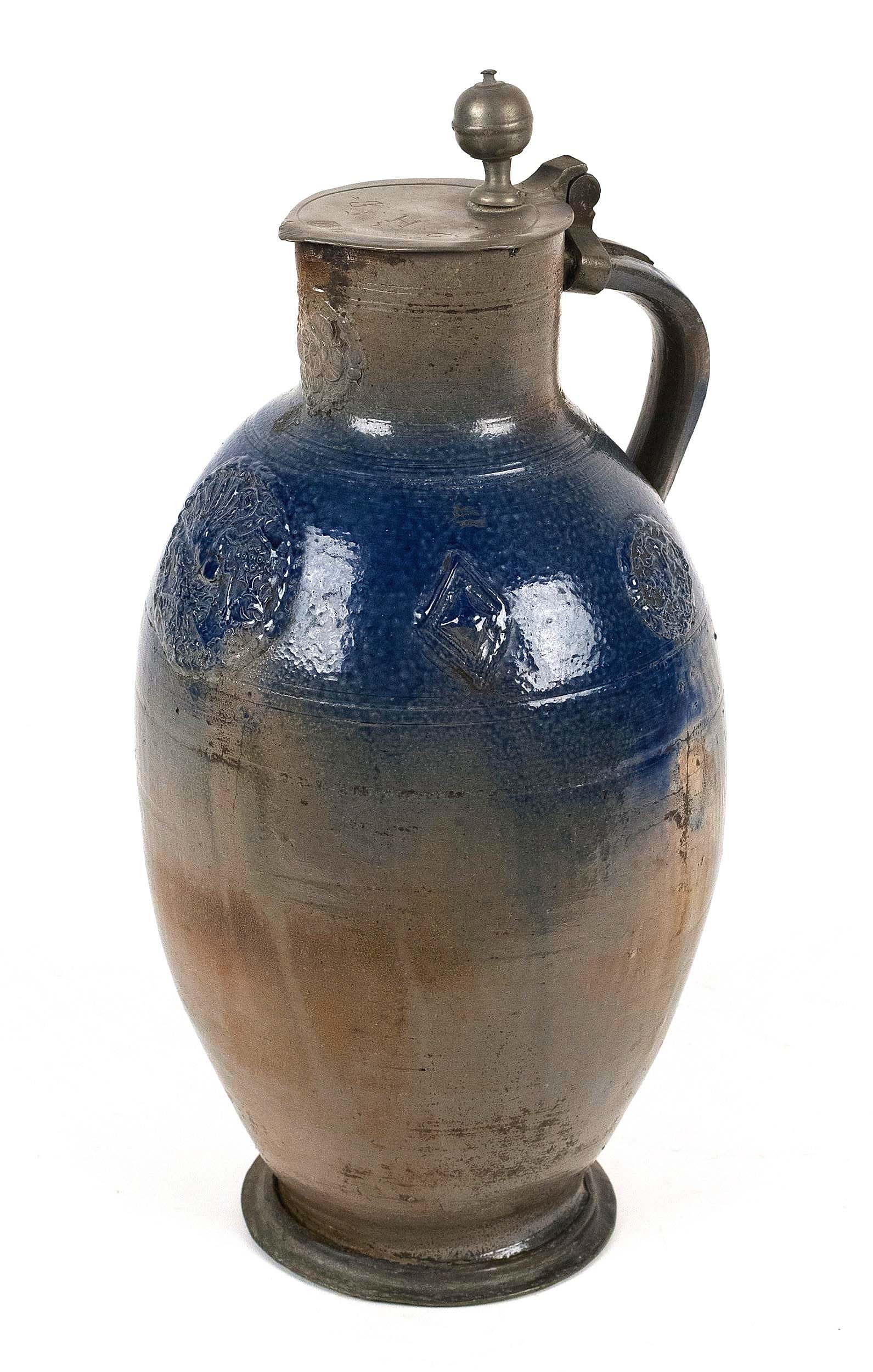

Cain lived in a Pilgrim Century house in Worthington, Mass.; her collection, which achieved a total of $159,000 and had been off the market for years, included numerous pieces of early furniture, Delft, needlework and carved bible or desk boxes. Leading the selection from the collection, and selling for $20,400, was a late Seventeenth Century carved bible or desk box. It retained much of its original blue-green painted surface, was missing its lock-plate and was thought to have originated in the Hudson River valley.

The Jerrilee Cain collection came from this first-period home in Worthington Mass. The house has been sold and Cain will be moving to the Midwest.

Much of the material in the Cain collection was purchased from leading dealers of the time, such as Lillian Cogan and Roger Bacon. For example, a circa 1720-30 Massachusetts William and Mary gate-leg table with a maple top, single pine drawer, sausage turned legs and stretcher, on original button feet, sold for $10,200. It had traces of old reddish brown paint. Cain bought it from Cogan who later offered to buy it back for the American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A circa 1730-50 small Massachusetts maple and pine gate leg table brought $4,800. It had an old painted surface, a rectangular top with two butterfly-hinged drop leaves, a carved apron, one dovetailed drawer and a stretcher base with strong vase and ring turnings. Cain also bought at major auctions, including the Garbisch sale, and from prestigious American dealers. She also bought from leading dealers of English and European furniture and decorative arts. Smith promoted the collection effectively and displayed it in the French house, a circa 1820 home on his property that he uses now and then to display early material.

From a different time and place, and from a different collection, a circa 1815 two-drawer stand with flame-birch veneered drawer fronts and a shelf, from the workshop of Judkins & Senter of Portsmouth, N.H., reached $8,400.

Made by Judkins & Senter of Portsmouth N.H., circa 1815, this two-drawer stand sold for $8,400.

With the help of a mutual friend, Antiques and The Arts Weekly had the opportunity to speak with Cain and discuss her collection and her reasons and attitudes towards collecting. Perhaps those attitudes differ from those of most Twenty-First Century collectors. She grew up in the 1930s and, for part of those years, she lived with her grandparents in a brick, circa 1830 farmhouse in rural Missouri. In her own words, “I’ve always remembered that house and that way of life; the smells of my grandmother humming and cooking, baking or making jams and jellies and the ‘make-do’ furniture which filled the house. Later, when I began to collect, each piece I’d bring home, to me, exuded the essence of that other non-technological way of life. That was sometimes more important to me than the piece itself. I like to think that in those times, the cabinetmaker actually knew the person for whom he was making a piece of furniture. Each piece reminds me of a time when every person in a community had a role to play in it: it blacksmith, potter, furniture maker, etc. I’d never been out of the Midwest. In 1949, when, as a sophomore at the University of Missouri, I took a class in art appreciation and saw slides of the first Seventeenth Century house I’d ever seen, I was hooked. It was the Whipple house in Ipswich, Mass. Then, when I visited the Jackson house — New Hampshire’s oldest house, in Portsmouth — it became my dream house. I decided I’d own a house like that someday and I’d fill it with special things. And I did.” Along the way, she restored a Nineteenth Century home, then an Eighteenth Century home and then the house in Worthington, which she bought in 1966. She finished by saying, “I’ve loved every pursuit, acquisition, and the people who have shared my love. It’s been an incredible journey. I’m more than satisfied with the prices my things sold for and I’m quite pleased with Leon Rogers and the rest of the Smith staff I dealt with.”

This full-bodied copper bull weathervane with a zinc head was still on the barn when its owner wanted to consign it. Leon Rogers climbed up to get it down for the auction and it sold for $6,600.

There was much more to Smith’s sale. Folk art included five nice weathervanes which brought unpredictable results. A Twentieth Century full-bodied copper pig weathervane, almost 30 inches long, with an old verdigris surface, sold for $7,800. An early full-bodied copper bull with a zinc head, a well-weathered surface with traces of gilt and later copper directionals earned $6,600. It came from an early Sharon Vt., farm, and as he was selling it, Smith commented that his associate, Leon Rogers, climbed to the top of the barn to get it down. A full-bodied copper, gilt decorated spread-wing eagle weathervane with an integrated ball and arrow directional, brought only $1,440. It measured 42 inches wide and its surprised buyer commented, “Where’d the weathervane buyers go?” Folk art included a 27-inch late Nineteenth Century carved and painted John Bellamy eagle in original paint, with a banner that read, “Don’t Give Up The Ship”; it sold for $7,200.

The large selection of fine art included numerous paintings and bronzes. A pair of monumental bronze dog sculptures by Jonathan Wylder led the selection, bringing $30,000. The standing dog was 46 inches tall while the reclining dog was 60 inches long. The pair was number two of an edition of four and were cast in 1998. They’re known as the “Talbot” dogs and appear on the coat of arms of the Duke of Westminster. Another pair is in Belgrave Square, Belgravia, London. Extensive documentation accompanied the bronzes. Bringing the same price of $30,000 was a silver casting of Frederic Remington’s, “The Outlaw,” with 1,000 troy ounces of .999 silver. It was authorized by the Frederic Remington Art Museum, produced by Silversmiths Group USA and cast by the Maiden Foundry in 2001.

The sale included an early White Mountain painting by an artist whose views of the mountains rarely come to auction. Painted, signed and dated (1854) by Julius O. Montalant, it realized $12,000.

A painting of the White Mountains, dated 1854 by Julius O. Montalant (American/European, 1823-1878) realized $12,000 and was the top selling painting. Although not titled, it is believed to be a scene from the peak of Mount Washington. At the time it was painted, neither the carriage road (now the auto road) nor the cog railway existed, so the artist would have had to climb the mountain, most likely with the help of a guide, to capture the view.

Smith was satisfied with the sale. A couple of days later, he said, “It was good to see interest in the American furniture: the Dunlap highboy brought about as much as it would have in the old days. Obviously, bidders liked the very small dropleaf, which went to a trade buyer. We were open on Memorial Day for previewing and that brought in a good crowd. There were probably about 150 people that day alone. Getting people to attend previews where they can see and handle stuff, and discuss it with us, is an ongoing challenge. We finished at just under a million dollars and that’s a number I like to see.”

For additional information, www.wsmithauction.com or 603-675-2549.