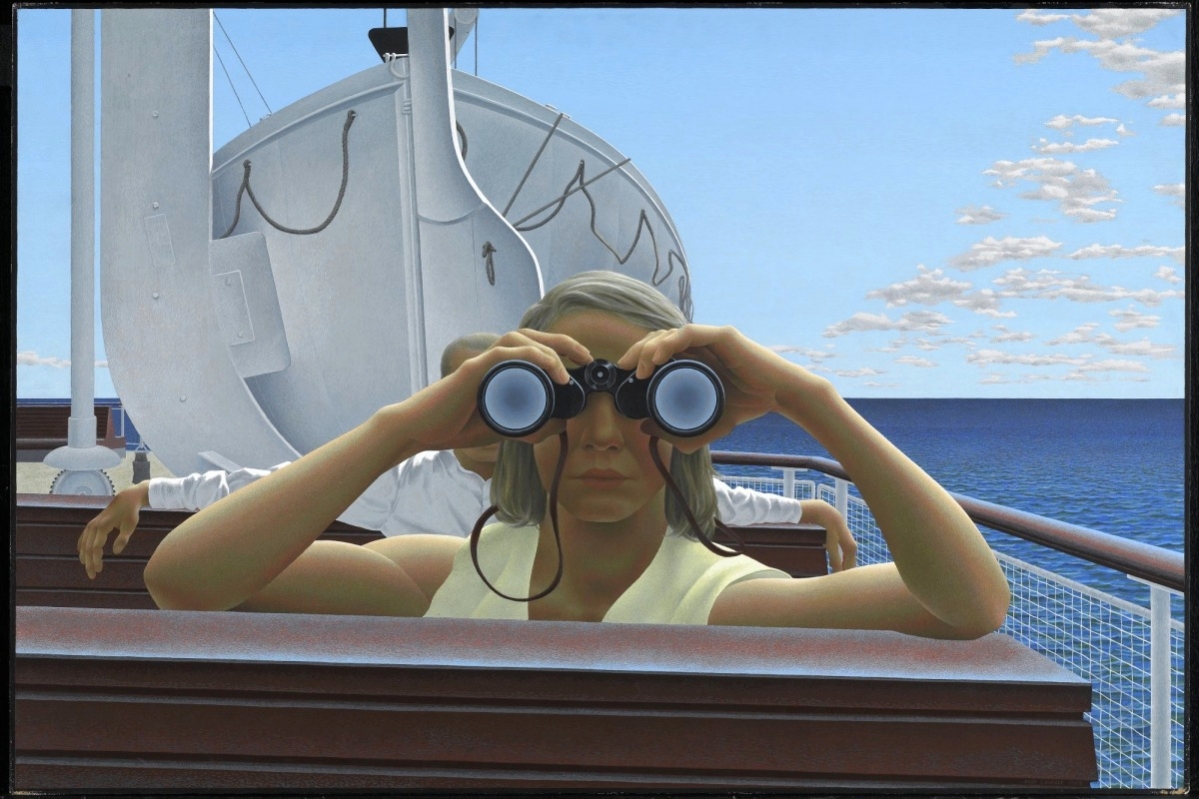

“To Prince Edward Island” by Alex Colville (1920–2013), 1965. Acrylic emulsion on Masonite. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Photo: NGC.

By Kristin Nord

OTTAWA – At the National Gallery of Canada’s entrance, a mini-landscape of pine, dogwood, wild grasses and iris evokes the smells and vegetation one would encounter in the boreal forest. The NGA, Ottawa’s own Crystal Palace, gleams in the sunlight, its interior spaces opened and enhanced by a multimillion-dollar renovation of one of Canada’s premier venues for looking and learning about art.

The new Canadian and Indigenous Galleries, which opened June 15, show off the space with aplomb, determined, according to Katerina Atanassova, the NGA’s senior curator of Canadian art, “to make the national collection more relevant and accessible to Twenty-First Century audiences, and to allow for more open dialogue, not just about the works in our collection, but also about the history of art in Canada.”

While the Canadian scholar and writer Hugh MacLennan explored the often-fraught relationship between his country’s French and English-speaking settlers in his classic 1945 novel Two Solitudes, a more contemporary history of Canada would probe many other solitudes, as well. The mingling of First Nations, Métis and Inuit people with immigrants from every region of the world makes for a rich, if complicated, story.

Known for his expertise in museum lighting and display, the Paris-based designer Adrien Gardére was brought on board to streamline rooms on the NGA’s second floor and make passageways more fluid, so as to facilitate, in Gardére’s words, “a real encounter between Indigenous and Western collections.”

In “Canadian and Indigenous Art: From Time Immemorial to 1967,” on view through September 4, Atanassova and colleagues have reframed the institution’s holdings chronologically and thematically, exploring across cultures such matters as the dignity of labor, inhabited landscapes and the Nineteenth Century portrait tradition. Christine Lalonde, associate curator of Indigenous art, borrowed 95 significant works from major institutions and private collections to enhance the presentation. Andrea Kunard, curator of the Canadian Photography Institute of the National Gallery of Canada, integrated the museum’s significant collection of photographs into this lively mix.

In “Canadian and Indigenous Art: From Time Immemorial to 1967,” on view through September 4, Atanassova and colleagues have reframed the institution’s holdings chronologically and thematically, exploring across cultures such matters as the dignity of labor, inhabited landscapes and the Nineteenth Century portrait tradition. Christine Lalonde, associate curator of Indigenous art, borrowed 95 significant works from major institutions and private collections to enhance the presentation. Andrea Kunard, curator of the Canadian Photography Institute of the National Gallery of Canada, integrated the museum’s significant collection of photographs into this lively mix.

Indigenous art advisory committees helped with the selection and interpretation of an astonishing range of work, from stone and ivory carvings, woven materials, regalia, beadwork and quillwork to paintings, sculptures and prints. These objects offer glimpses of life before the arrival of Europeans, when regalia were created for particular ceremonies, and continue up to the late 1960s, when artists of the Woodland School and the West Baffin Island Eskimo Co-operative became part of the mainstream.

There are remarkable objects, such as a ceremonial coat made of embellished caribou hide that is believed to have been worn by a shaman and once imbued with magical powers. An iconic Algonquin birchbark canoe evokes both the early years of Indigenous life and settlers’ expeditions.

“Blunden Harbour” by Emily Carr (1871–1945), circa 1930. Oil on canvas. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Photo: NGC.

Before the galleries reopened, the sweet smell of burning sage filled the rooms as members of Kitigan Zibi First Nation, on whose traditional territory the museum was built, conducted smudging ceremonies to cleanse and purify spaces and objects. For many pieces, labels appear not only in English and French, but also in the native language of the Indigenous artist. Multicultural and multilingual, Canada’s history is as complex as its horizons are broad and distances vast.

Canadians of European descent are represented by a Nineteenth Century portrait by William Berczy, a majestic landscape by Lucius O’Brien and sculpture by the founder of the Canadian Academy of Arts, Louis-Philippe Hebert, who created more than 40 Canadian monuments. There is a battle scene by French Canadian artist Joseph Légaré, a Montreal street scene by William Raphael and a luminous nautical portrait by John O’Brien, Canada’s first professional marine painter. In all, almost 800 works are featured in the new installation.

Careful efforts have been made to give important women artists their due. On view are Yvonne McKague Housser’s abstract and psychological renderings of hearth, as well as Paraskeva Clark’s paintings, replete with political commentary. In a room highlighting women artists of Montreal’s Beaver Hall Group, Prudence Heward’s fierce portrait of a country woman in an acid-pink apron is a notable stunner. As ever, the absorbing work of Emily Carr, with its depictions of the landscape of British Columbia and First Nations settlements, exerts a vibrant pull. It seems fitting that her art is displayed next to exquisite beaded footwear on loan from the Bata Shoe Museum.

Tureen with the crest of the Hertel de Rouville family by Laurent Amiot (1764–1839), 1793–94. Silver. This vessel by a Paris-trained smith was hailed as the most significant piece of Canadian silver when Waddington’s offered it in 2015. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Photo: NGC.

In the Michael and Sonja Koerner Family Atrium, a new floating wall features late-Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century bronze sculptures by Louis-Philippe Hébert and Alfred Laliberté on one side and a contemporary work by Anishinaabe artist Michael Belmore on the other.

The Royal Canadian Academy of Arts was founded in 1880 to foster the development of the country’s visual arts. In 1885, the Canadian government banned the art-centric Potlatch ceremonies as part of its efforts to assimilate Northwest Coast aboriginal groups. For more than 100 years many First Nations artists either went underground or found ways to produce material for growing tourist markets. In the new galleries, Potlatch objects are brought back into the story of late Nineteenth Century art. Such tangible efforts to acknowledge the “hard truths” of history – to this American, at least – suggest Canadians are serious about telling the story this time around. “We can’t change history,” Greg A. Hill, the Audain senior curator of Indigenous art, said in a recent interview. “But we can draw upon recent scholarship to tell the story more fully.”

Not only does 2017 mark the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation, but it also coincides with the centennial of Group of Seven member Tom Thomson’s death. The National Gallery owns the majority of his works, including “The Jack Pine,” a masterpiece. His sky studies, small oil paintings on Masonite that he completed en plein air, fill an entire wall. Thomson and other members of Canada’s foremost circle of early Modernists remain a riveting force, their paintings commanding multimillion-dollar prices at auctions when they come on the market and ranking overall among top Canadian sellers.

“Man in Kayak,” artist unknown, circa 1900–60. Ivory, red and black plastic, and black thread. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Photo: NGC.

But Canadian art in general has been eliciting attention and garnering big prices in auctions in the United States and abroad. In 2013, a Jack Bush painting sold for ten times its high estimate at Christie’s in New York City, while “The Crazy Starr” by Emily Carr brought in $3.39 million in Canadian dollars, the most ever paid at auction for a Carr painting, at Heffel Fine Arts in Toronto that same year.

The 2015 traveling show “The Idea of North: The Paintings of Lawren Harris” reintroduced the work of Harris, a prodigiously talented member of the Group of Seven, to the American public in exhibitions at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Among the 30 paintings on loan was Harris’s “North Shore, Lake Superior,” currently on view at the National Gallery. Entertainer and collector Steve Martin, the exhibition’s curator, ranks Harris among the major painters of the Twentieth Century. Of this arresting work, he told Michael Enright of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, “There’s a lone dead tree, almost dead center, which is usually something an artist would not do. But somehow it works. Here’s a real example of nothing living – you have a dead tree, and yet in the background you have these incredible burst of sun rays, and the light reflecting on water. And it’s an optimistic painting. It’s almost like a phoenix rising.”

The National Gallery of Canada is at 380 Sussex Drive. For more information, www.gallery.ca or 613-990-1985.

Journalist Kristin Nord divides her time between Connecticut and Nova Scotia.