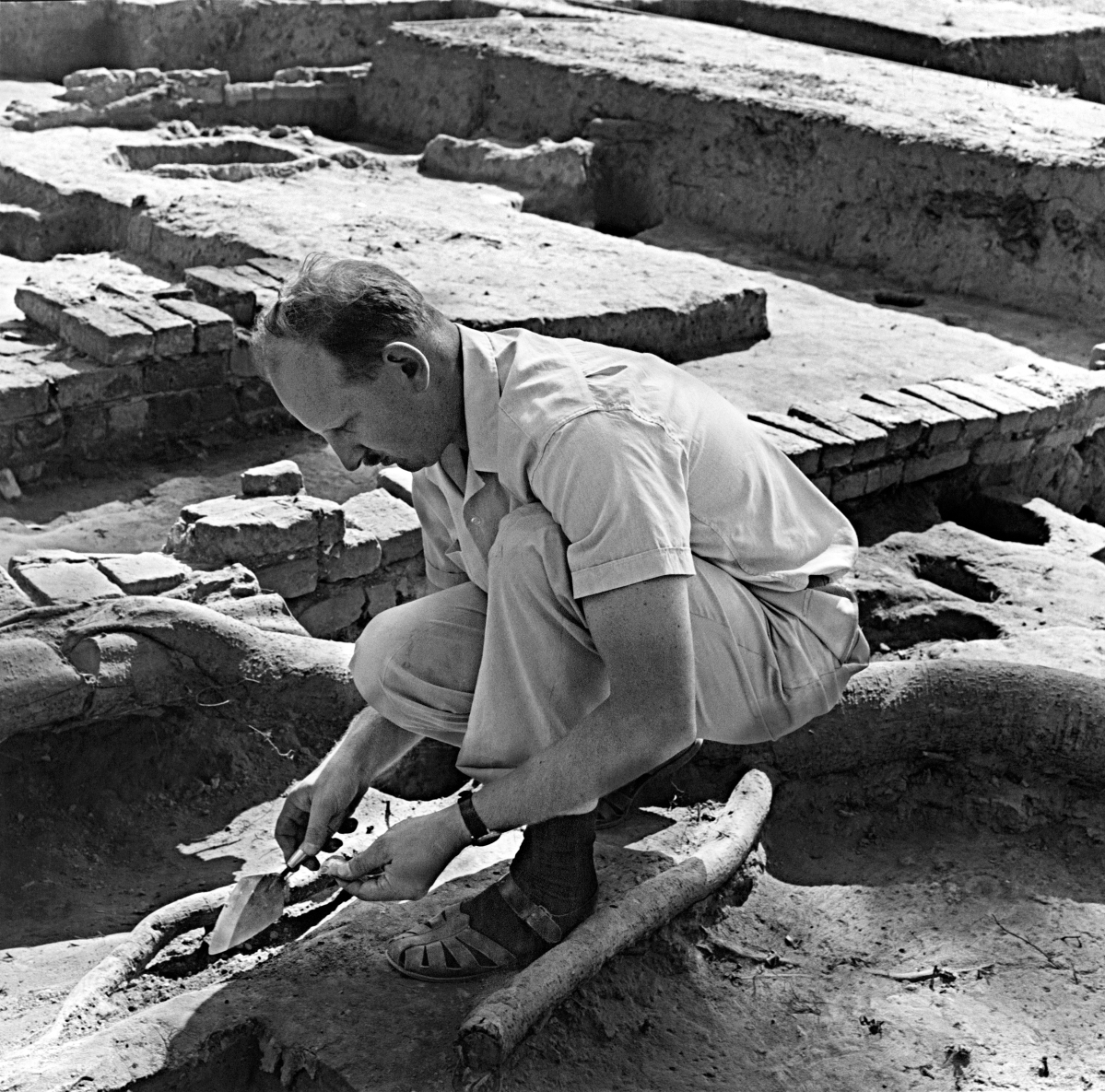

Ivor Noël Hume during excavations of Henry Wetherburn’s Tavern, 1965. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation photo.

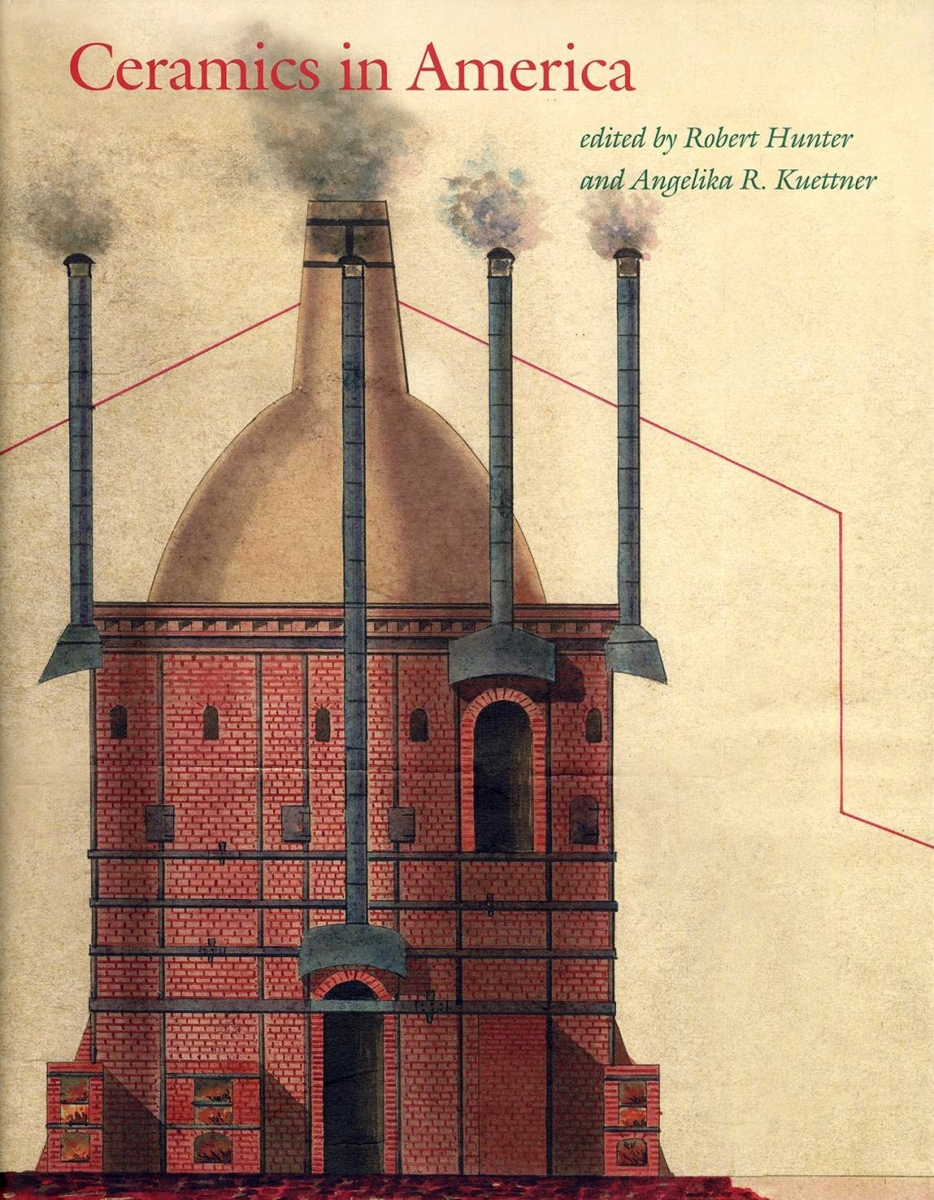

Ceramics in America 2017 , edited by Robert Hunter and Angelika R. Kuettner; Hanover and London: Published by the Chipstone Foundation, distributed by University Press of New England; 232 pages; 280 color illustrations; hardcover; $65.

Old bones, old pots – there is something exciting about the discovery of both. So when a recent news article about the discovery by archaeologists of the remains of one of Jamestown’s early settlers – possibly those of Sir George Yeardley, who oversaw the first representative government assembly in English America and was also one of America’s first slaveholders – it resonated with an essay by Merry Outlaw, curator of collections for Preservation Virginia, that concludes the 17th volume of Ceramics in America, the Chipstone Foundation’s annual journal.

Yeardley figures in her discussion of “Jamestown and Governor’s Land, James County, Virginia,” as he is instructed by the Virginia Company in 1618 to “set aside 3,000 acres on the ‘Main,’ or mainland,’ conquered or purchased from the Paspegegh Indians.”

It may take researchers a while to determine if the skeletal remains found in the grave are actually Yeardley’s – it seems the skull is missing, although teeth unearthed there could provide some clues – but in terms of the items like clay pipes and pottery shards testifying to early Seventeenth Century lifestyle and commerce, a clear picture emerges from Outlaw’s chapter as well as one by Bly Straube, curator, Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, contained in this volume.

Indeed, the theme of celebrating discovery runs through this book. Co-editor Robert Hunter, dedicating his introduction to the life and legacy of Ivor Noel Hume, who passed away on February 4, 2017, provides a valuable overview to the volume’s 15 essays. Represented here is a span of more than three-and-one-half centuries where archaeological research, art history, social and economic history, material culture, scientific analysis and conservation all converge to illustrate the perpetual human fascination with what can be fashioned from earthly elements.

Perhaps the most poignant contribution is from Hume, described as “a long-time friend and contributor to the journal.” In a playful piece titled “A Devil in the Details,” the late British-born archaeologist, author and former director of Colonial Williamsburg’s archaeological research program recounts how he was punked by Hunter and American contemporary artist Michelle Erickson in a dimly lit bistro when they presented him with a new “discovery” in the form of a unique sprig-decorated tavern mug, purportedly from London. The light-hearted essay, summarized by Hume to show the perils of expert pontification during a candlelit dinner, sets a playful tone leading into the 14 subsequent articles that more seriously highlight important ceramic discoveries from archaeological contexts in St Augustine, Fla.; Charleston, S.C.; New Orleans, La.; Alexandria, Hampton, Williamsburg and Jamestown, Va.; St Mary’s City, London Town and Annapolis, Md.; Philadelphia, Pa.; New York City; and Boston and Plymouth, Mass.

Those simple, place-name titles indicate the wide-ranging nature of the discoveries presented here. For example, co-editor Hunter himself weighs in with “Hampton, Va.,” a profile of the Hampton Roads gateway, one of the world’s largest natural harbors as well as the oldest continuous English-speaking settlement in North America. The focus of intense archeological investigations, the area has disgorged evidence of Native American settlements, Seventeenth Century plantations and Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century dwelling, and Hunter proceed to highlight some of the key finds, ranging from a Sixteenth Century German slipware two-handled pot to a Civil War-era utilitarian dipt ware pitcher, probably from Staffordshire, England, exemplifying scorching from the August 1861 Confederate burning of Hampton under Brigadier General John B. Magruder.

-1024x832.jpg)

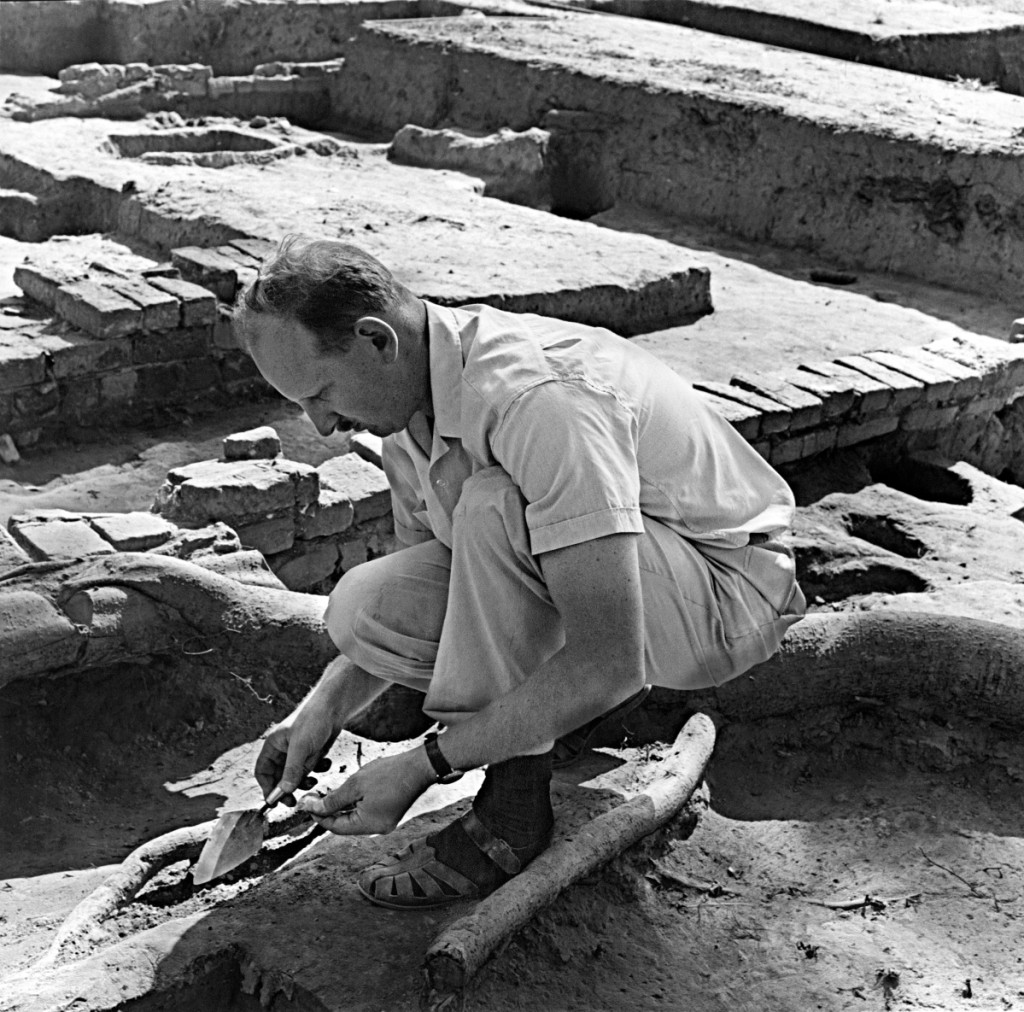

Chamber pot, attributed to Ferrybridge & Co, Yorkshire, England, circa 1796–1801. Creamware, diameter 8¼ inches. Marks: stamped “Wedgwood” and “3.” Courtesy Alexandria Archaeology Museum. Robert Hunter photo. Banded and sponged. Two of these pots were found together in the same privy at an apothecary shop, where they were deposited around 1800–20 along with eight plain creamware chamber pots.

Along the way in the journal’s vicarious journey, readers are regaled with such interesting asides as in Barbara Magid’s treatise on Alexandria, Va., in which the author describes what may be “the ugliest pots in Alexandria.” They were either designed for the American taste or exported after not finding a domestic market, she posits, and are exemplified by a chamber part, one of a matched pair discarded in the early 1800s in a privy behind an apothecary. With bands of slip unevenly applied, the pieces are further made unattractive by unusual, splotchy sponge decoration.

Hume’s role in shaping the archaeology program in Williamsburg, Va., is related by Suzanne Findlen Hood in the Tidewater town chapter. The curator of ceramics and glass at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation notes that not only was he a prolific author of books and articles but also exhibited a contagious passion for “the systematic retrieval of all artifacts, not just those that were pretty or unusual . . .”

This volume, along with the 16 that precede it, is an important resource for years to come for anyone with an interest in America’s ceramic history. The sheer diversity of ceramic forms and types that have been uncovered through archaeological research is in itself compelling, but even more so are the stories of early American exploration and life teased out by those like Hume and his colleagues. As Hood declares in her essay, “‘We know it was here because of archaeology’ is still one of the strongest reasons to add a particular ceramic object to the collection.”

Those with highly specific interests within the realm of ceramics made and used in America may want to check out the table of contents online at UPNE Book Partners Chipstone Foundation: www.upne.com.

– W.D.

.jpg)

.jpg)

_07zw.jpg)

.jpg)