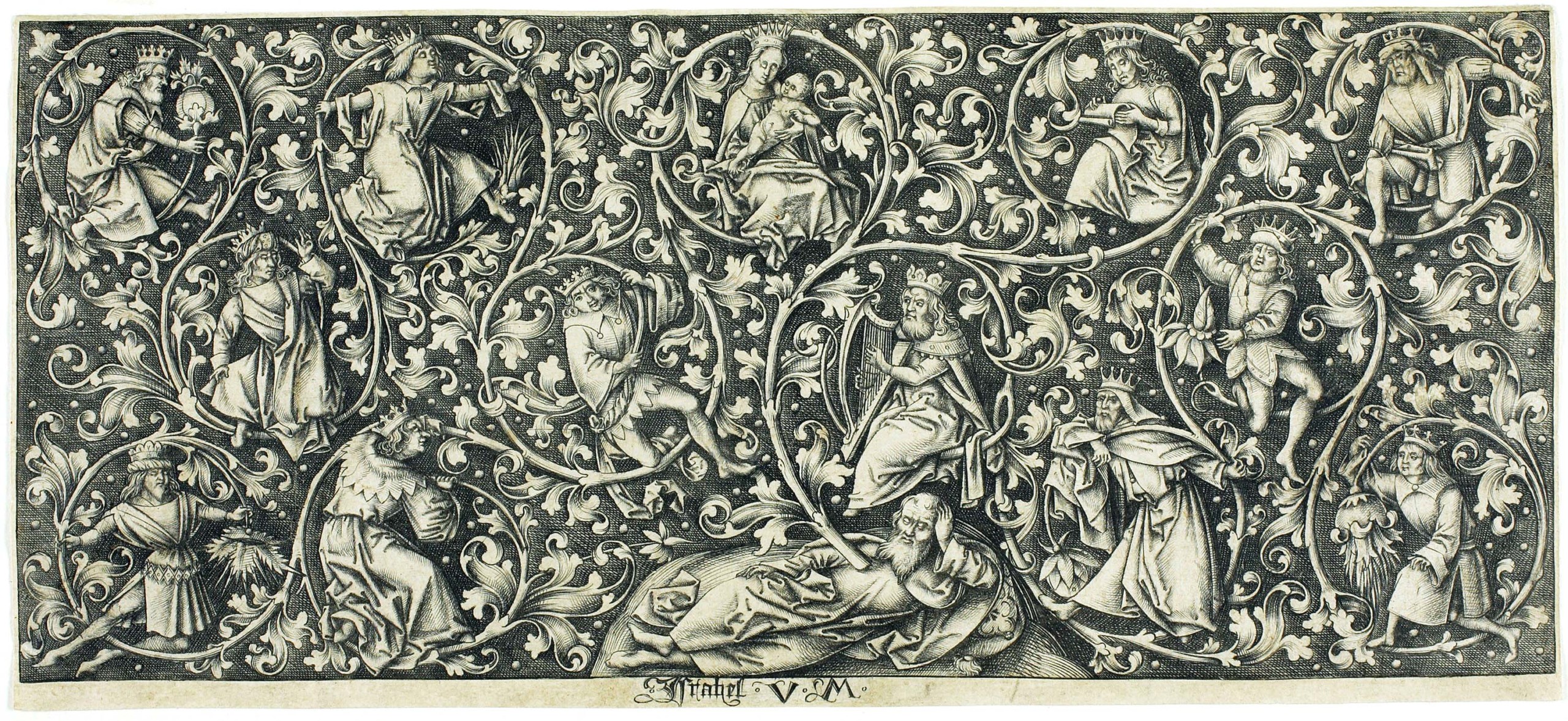

“Ornament with the Tree of Jesse” by Israhel van Meckenem (German, 1440/1444-1503), 1480-90, engraving on paper. Clarence Buckingham Collection, Art Institute of Chicago.

By James D. Balestrieri

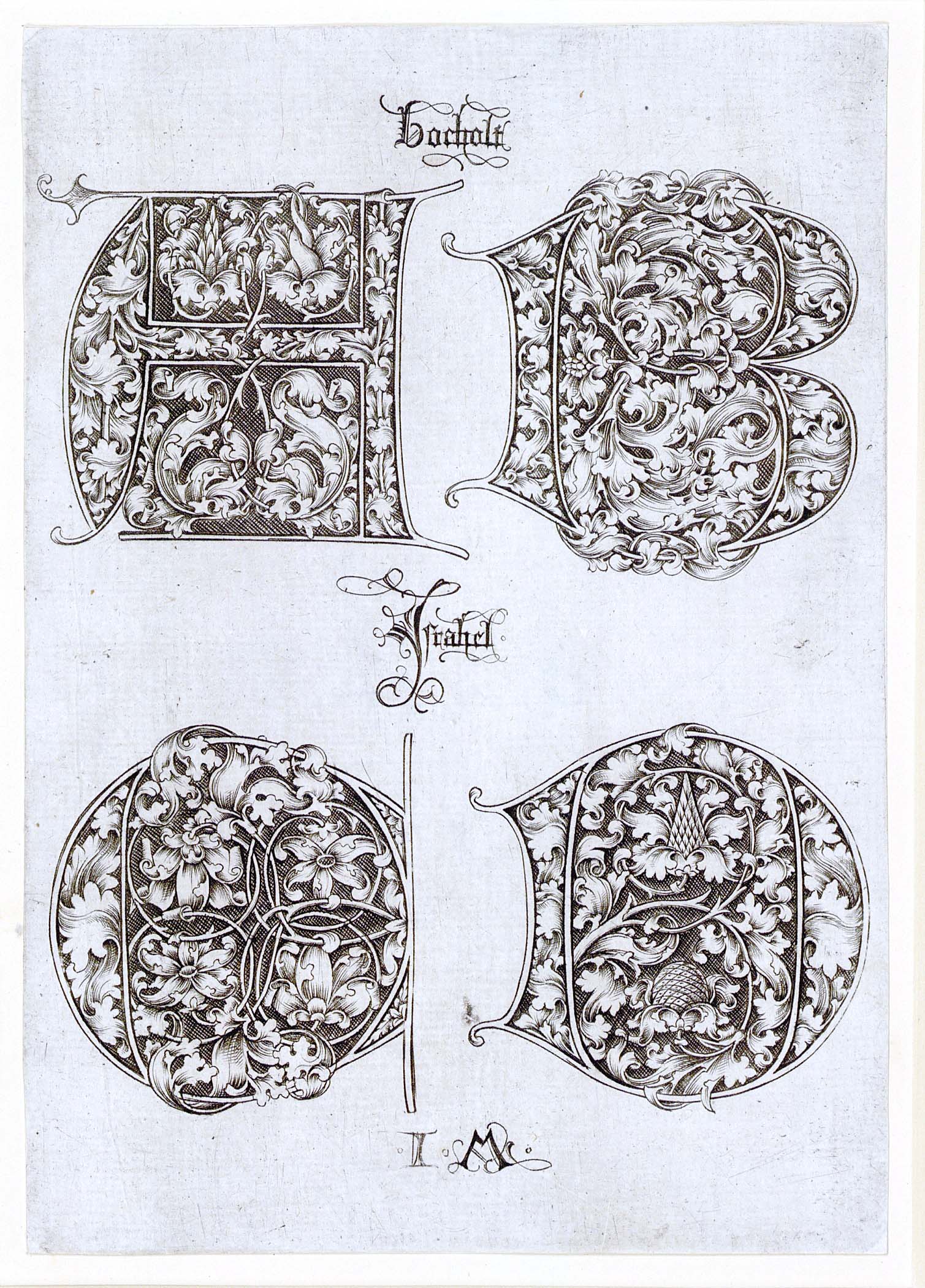

MADISON, WIS. — What constitutes “fair use” in the digital world, where images ride electrons? What does “original” mean in a world where A.I. “creates” art? What does “art” mean in a world where, to paraphrase a recent statement from jazz great Herbie Hancock, people are more interested in the artist than they are in the art? “Art of Enterprise: Israhel van Meckenem’s Fifteenth Century Print Workshop,” on view at the Chazen Museum of Art at the University of Wisconsin–Madison is an ideal exhibition for our times, examining exactly these subjects of authenticity and authorship, the culture of copying, the question of appropriation and the novelty of entrepreneurship and branding at their origins in Western visual culture. As contemporary artists grapple with these same issues in the digital world, and with the advent of A.I., Chazen curator James Wehn confirms this, saying, “In the late Fifteenth Century, when Israhel was copying existing images, the value was in the labor and the materials and not in the image. Today, we face similar questions about authorship and the value of intellectual capital with A.I. technology. ‘Art of Enterprise’ will present Israhel van Meckenem’s work and encourage visitors to consider concepts of originality that were called into question then and remain relevant in today’s digital world.”

None of this is new. Advances in lithography in the middle of the Nineteenth Century and the availability of prints to a wider audience sent shock waves through the art community. The lithograph seemed to signal the end of painting (Hint: it did not).

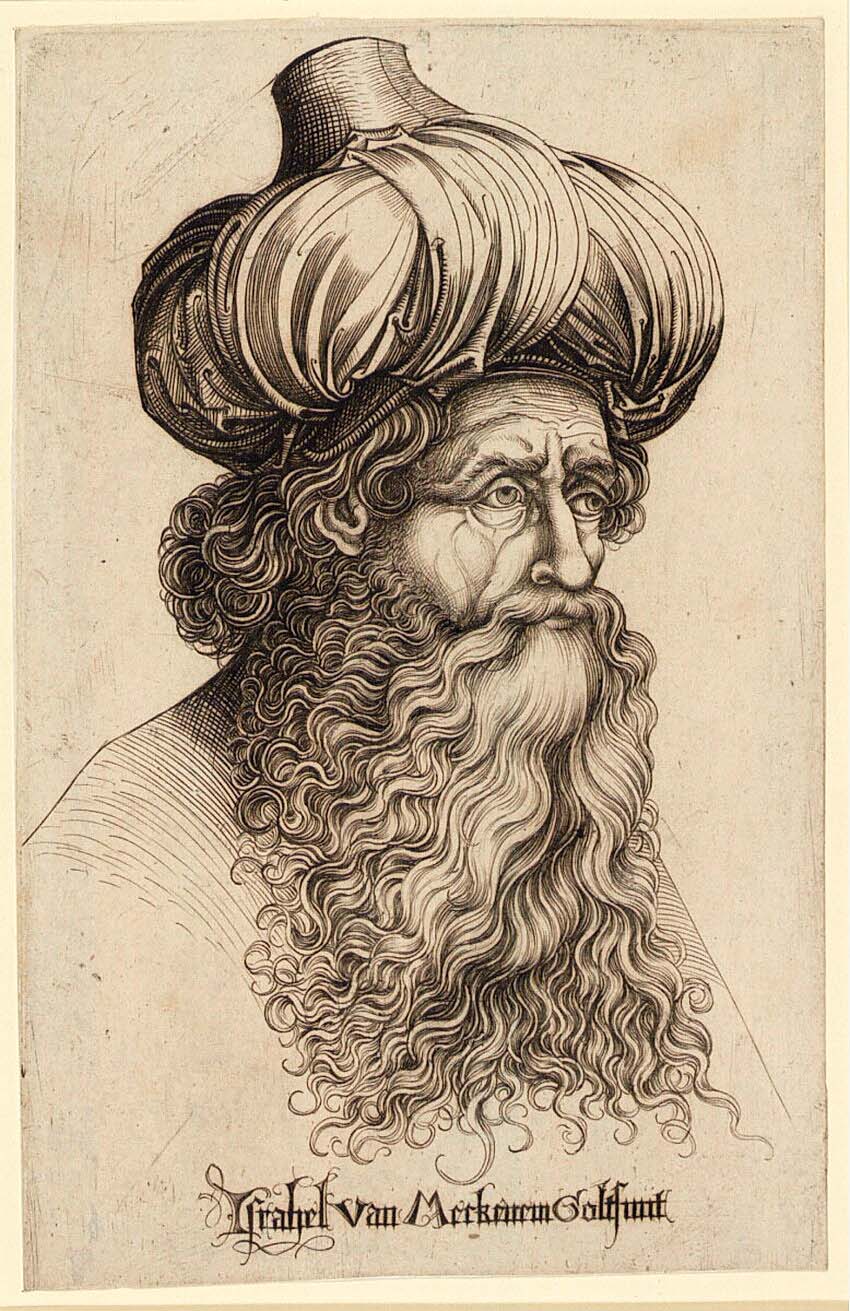

Israhel van Meckenem (1440/1444-1503) was German, though possibly of Dutch origin. He was himself a goldsmith and engraver, as was his father. The majority of his print output consists of copies of engravings by other contemporary master printers, including Master E.S. (with whom he may have studied), Martin Schongauer, Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein the Elder. Israhel’s copies, however, reflect the personal style he developed; his original engravings, including the “Double Portrait of Israhel van Meckenem and his Wife Ida,” circa 1490, which is considered the first self-portrait in the history of printmaking, display a marked sensitivity, a secular humanism, if you will, that transcends the liturgical, mythological, and heraldic subject matter that dominated the market at the time. In addition to broadcasting his own image, Israhel “branded” his work with his initials and name and his prescience and reworked engravings so they could be placed in books as illustrations, ensuring that they would be broadcast beyond the area where he lived and worked, and becoming, in their way, advertisements for his artistry and services.

“Double Portrait of Israhel van Meckenem and his Wife Ida” by Israhel van Meckenem (German, 1440/1444-1503), circa 1490, engraving. Hofbibliothek, Albertina Museum.

It would be intriguing to know who the intended audience was for “Double Portrait of Israhel van Meckenem and his Wife Ida.” Up above, I described the image as “sensitive” and suggestive of “secular humanism.” Yes, this is projection on my part (at least I steered away from the word “realism”). What I am supposed to do is assume some agenda on the part of the artist, to locate the work in the social milieu of the era. What ideologies lie beneath the image? What is it trying to advertise? Fine. I’ll play. What I see is a middle-aged, middle class couple — this at the beginning of the rise of a middle class of artisans and merchants — content with one another and their situation. No finery adorns them but their clothes are crisp and clean. The tapestry that hangs behind them unites them in natural symbols and weaves them together. The curls that escape Israhel’s cap suggest youthfulness, even in middle age and Ida’s round chin indicates a certain joviality. Their love for one another is apparent and bound in contentment. What you are also looking at is a look book of technique. The engraving demonstrates mastery of line, crosshatching and shading, as well as a keen understanding of inking darks and lights in printmaking. The title and maker are at the bottom in Latin. For good measure, Israhel’s initials are there too. If you stopped by Israhel’s workshop to inquire about a commission, you would probably get a mug of hot punch from Ida. You’d be in good hands.

In short, the print works on any number of levels, as an early representation of public selves that also reveals a great deal about the people behind and beneath those selves. “Double Portrait of Israhel van Meckenem and his Wife Ida” emerges as a mask that reveals even as it conceals, which makes it an outstanding portrait and artwork in its own right. Contrast this with Dürer’s “The Ill-Assorted Couple,” circa 1495, which shares the sensitivity of the “Double Portrait” — but from an ironic distance — and any cynicism about the meaning, purpose and intention of Israhel’s work seems to fall away.

“The Ill-Assorted Couple” by Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528), circa 1495, engraving. Bequest of John H. Van Vleck, Chazen Museum of Art.

Contrast both the “Double Portrait” and “The Ill-Assorted Couple” with the images of saints that were Israhel’s bread and butter. They are iconic, in the sense of iconographic, derivative of and derived from a tradition of manuscript illumination that already dated back centuries in Israhel’s lifetime. Saint Peter, absorbed in scripture, holds the key to the church, to Christianity. Saint John the Baptist holds the chalice that signals the first sacrament. The print of Saint Judas Thaddaeus, circa 1470, is more problematic as the two-handed saw he holds is more closely related to Saint Thomas the Apostle, also known as Judas Thomas, an architect who traveled at least as far as India spreading the Gospel, and was martyred there in what is now the city of Chennai, in 72 CE than it is to Saint Jude, the patron saint of lost causes, who is most often depicted with a club. Because of the many changes in the names of saints and other figures in scripture over centuries, one can see how, in a culture of copying potential errors in iconography would be passed down, amplified, and find their way into the history of Christianity in a game of telephone not unlike the culture of rumor an alternative facts that calcify into faux truths in the internet era.

Israhel’s “Five Foxes,” circa 1490, takes us beyond the medieval realm of the bestiary, the book of venery (heraldic manuals of hunting), and the moral fairy tale on the order of Aesop. The image, which appears to be original, points to a close observation of nature and the influence of the resurgence of classical scientific philosophy that marked the Renaissance in Europe. The five images in one depict foxes in different poses — grooming, watching while at rest, and tugging at prey. Without any background other than the suggestion of two low hills, the effect is diagrammatic, as if we are looking at a treatise on animal behavior. One imagines this image illustrating Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura, or another similar classic.

“The Five Foxes” by Israhel van Meckenem (German, 1440/1444-1503), circa 1490, engraving on ivory laid paper. Clarence Buckingham Collection, Art Institute of Chicago.

Israhel’s pictorial imitation of the fox in nature brings us back to the question of imitation and, finally, to some larger questions. Something in “Art of Enterprise: Israhel van Meckenem’s Fifteenth Century Print Workshop” reminded me of an old ad — catchy and successful, by the way — for Memorex cassette tapes asked, “Is it live or is it Memorex?” Since you were watching the ad on TV, how could you know and what did it matter anyway? What mattered was the fact that it was Ella Fitzgerald scatting and (perhaps) breaking a glass with her (recorded) voice. Strip the Memorex marketing away. The art wasn’t in the technology — or in the ad — it was in Ella. Why do you think Memorex hired her in the first place? The originality and beauty in “Double Portrait of Israhel van Meckenem and his Wife Ida” and “Five Foxes” bring me to the same conclusion — the art is in Israhel, not in his branding, entrepreneurship, or in the fact that his job was, in part, to copy the work of others.

What’s more, the exhibition, as I see and “read” it, asks what it means — not only for art, but for society — when any expression can be art, when anything anyone calls art is art? The jury is out on that answer. Because we can’t, or won’t answer that question, discussions of art now center on new media, actively avoiding meaning, quality and value. We shy away from such discussions because — rightly — we don’t want to apply some mysterious universal benchmarks to art that would invariably, as they always have, marginalize and exclude some artists from a made up canon. But when we are so caught up in whether some sort of social media gesture is or is not art, or whether an A.I. generated image is or is not art, what we’re not talking about is how those works, however they are made, move us, inspire us, shock us, endorse or subvert some ideology (or both), are useful to us — or provide an escape, remind us that there is beauty in the world, or caution us to be wary of beauty or any other aesthetic category.

“Christ the Redeemer (Salvator Mundi)” by Israhel van Meckenem (German, 1440/1444-1503) circa 1490-1500, engraving. John L. Severance Fund, Cleveland Museum of Art.

Not too long ago, on a Sunday morning, I was with my family at a yard sale. My wife was drawn to an old, framed print. For the sake of going against the current grain, I won’t name the artist or the print. Doesn’t matter. I felt it might be priced at $200 or more and just didn’t feel like dishing that out. We were going to pass. I looked at it again. It was an Eighteenth Century mezzotint and had the names of the artist (with the Latin “pinxt,” or “painted by”), the engraver (the Latin “sculpt” as sculpture embraced engraving then) and the name of the printer. My daughter encouraged me to ask. What could it hurt? Long story longer, $20, I bought the print, and the owner threw in a cold Pabst. I hadn’t had a breakfast beer in many decades, but I didn’t feel that I should be less than convivial. What can I say, it was a hot day. What struck me is that, at each step, the artists — painter, engraver, printer — were engaged not in a practice of copying, but rather, of translation from a conception formed in the painter’s mind that he himself — and it was a he — translated into paint on canvas. Each step was new, original in its own way.

Before you go down the media rabbit hole into sociology and historicity when you look at an artwork, especially the prints in “Art of Enterprise: Israhel van Meckenem’s Fifteenth Century Print Workshop,” ask yourself the big questions: Does the work work? Is it engaging? Does it aspire to something beyond itself? Is it relevant? Is it visionary? Does it make you see in a new way? Does it make you feel?

“Art of Enterprise: Israhel van Meckenem’s Fifteenth Century Print Workshop” is on view at the Chazen Museum of Art through March 24.

The Chazen Museum of Art, on the campus of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, is at 750 University Avenue. For more information, www.chazen.wis.edu or 608-263-2246.