“Waterlilies and Japanese Bridge” by Claude Monet, 1899. Oil on canvas, 35-5/8 by 35-5/16 inches. Princeton University Art Museum: From the Collection of William Church Osborn, class of 1883, trustee of Princeton University (1914–1951), president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1941–1947); given by his family, 1972–15. Photo Credit: Princeton University Art Museum/Art Resource, NY.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

DENVER, COLO. – America just can’t get enough of Claude Monet. This has been true since the 1880s, when American collectors started acquiring Impressionist paintings in earnest, and carried through to the 1980s, when exhibitions headlined by Monet brought the term “blockbuster” to the museum world. Four decades later, Monet’s ability to drive crowds to North American venues is undiminished. The Los Angeles Times dubbed 2019 “The Year of Monet,” with five exhibitions taking place this year in the United States (and another just over the border in Toronto). Of these, “Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature,” co-organized by the Denver Art Museum (DAM) and the Museum Barberini in Potsdam, Germany, and on view in Denver through February 2, is by far the most sustained look at this Impressionist master.

The exhibition, in part, celebrates the 2014 bequest of Frederic C. Hamilton, which brought 22 Impressionist masterworks to DAM, including four paintings by Monet and several by his teacher, Eugène Boudin. These joined DAM’s already strong holdings of works by both artists, some of which were lent to the Barberini for their exhibition “Impressionism: The Art of Landscape” in early 2017. At the opening reception, DAM director Christoph Heinrich remembers, he and the Barberini’s Ortrud Westheider (they “go way back,” Heinrich says) began a conversation about how they might collaborate on a show that would represent the “bandwidth” of Monet’s career and highlight the breadth of the DAM’s holdings, which date from 1868, when Monet was still a fledgling artist, to 1903, when he was beginning the most experimental work of his career.

The idea they developed, along with DAM chief curator Angelica Daneo, turned out to be about much more than just Monet’s longevity, range or enduring appeal. Heinrich says that, before now, “there has not been a Monet show done around his dialogue with nature, and specifically the way that he was looking for certain places, how places influenced him.” Two recurring themes intertwine throughout the present show: Monet’s well-known practice of engaging with the same place over and over again, over a long period of time, in different seasons, times of day and atmospheric effects; and a less-recognized, and somewhat revolutionary, revelation that, in doing so, Monet was not, as a rule, simply taking inspiration from what he saw, but rather specifically looking for scenes that matched an idea of nature he already had in his mind.

This is nowhere more evident than in the works he produced in the south of France and Bordighera, Italy, in the 1880s, and in the letters that he wrote about them – which Daneo dug into for her excellent essay in the catalog, titled “‘These palm trees are driving me crazy’: Monet, the South, and the Intentional Motif.” The quip is Monet’s own, from a letter to his second wife, Alice, wherein he expresses frustration that the lush landscape of the Riviera won’t accommodate itself to his interior vision. “When you’re looking for motifs,” he writes, “it’s very difficult. I would like to paint some orange and lemon trees standing out against the blue sea, but I can’t find them the way I want them.”

This simple statement turns on its head the commonly received wisdom that dictates Impressionism is about spontaneously capturing a fleeting impression of nature. “There is this narrative in the general public,” Daneo observes, about how the “Impressionist artist brings his little suitcase of colors and finds an inspiring place and paints it the way he sees it.” But Monet’s correspondence and his carefully curated set of images – similar motifs of lone windswept trees appear in both Bordighera and in Trouville, on France’s Normandy coast, for instance – challenge this. Together, Daneo says, they show “that he had clearly intentional compositions before he set out to go into nature…[that he was] driven to nature to find that composition that he had into his mind.”

But we are somewhat ahead of ourselves, for the exhibition begins at the beginning, in northern France, where Monet spent the early years of his life and where as a young man he met and painted alongside Eugène Boudin. A highlight of the show, Heinrich says, is the first canvas that Monet exhibited publicly and was comfortable calling his own: “View from Rouelles,” completed in 1858, when he was only 18. Shown alongside a contemporaneous Boudin of essentially the same scene, Monet’s painting shows the influence of his teacher and their mutual involvement in the Barbizon School, which sought to dismantle the rigid academic traditions of classical landscape painting and find beauty in the overlooked, in nature unadorned and unmediated.

But we are somewhat ahead of ourselves, for the exhibition begins at the beginning, in northern France, where Monet spent the early years of his life and where as a young man he met and painted alongside Eugène Boudin. A highlight of the show, Heinrich says, is the first canvas that Monet exhibited publicly and was comfortable calling his own: “View from Rouelles,” completed in 1858, when he was only 18. Shown alongside a contemporaneous Boudin of essentially the same scene, Monet’s painting shows the influence of his teacher and their mutual involvement in the Barbizon School, which sought to dismantle the rigid academic traditions of classical landscape painting and find beauty in the overlooked, in nature unadorned and unmediated.

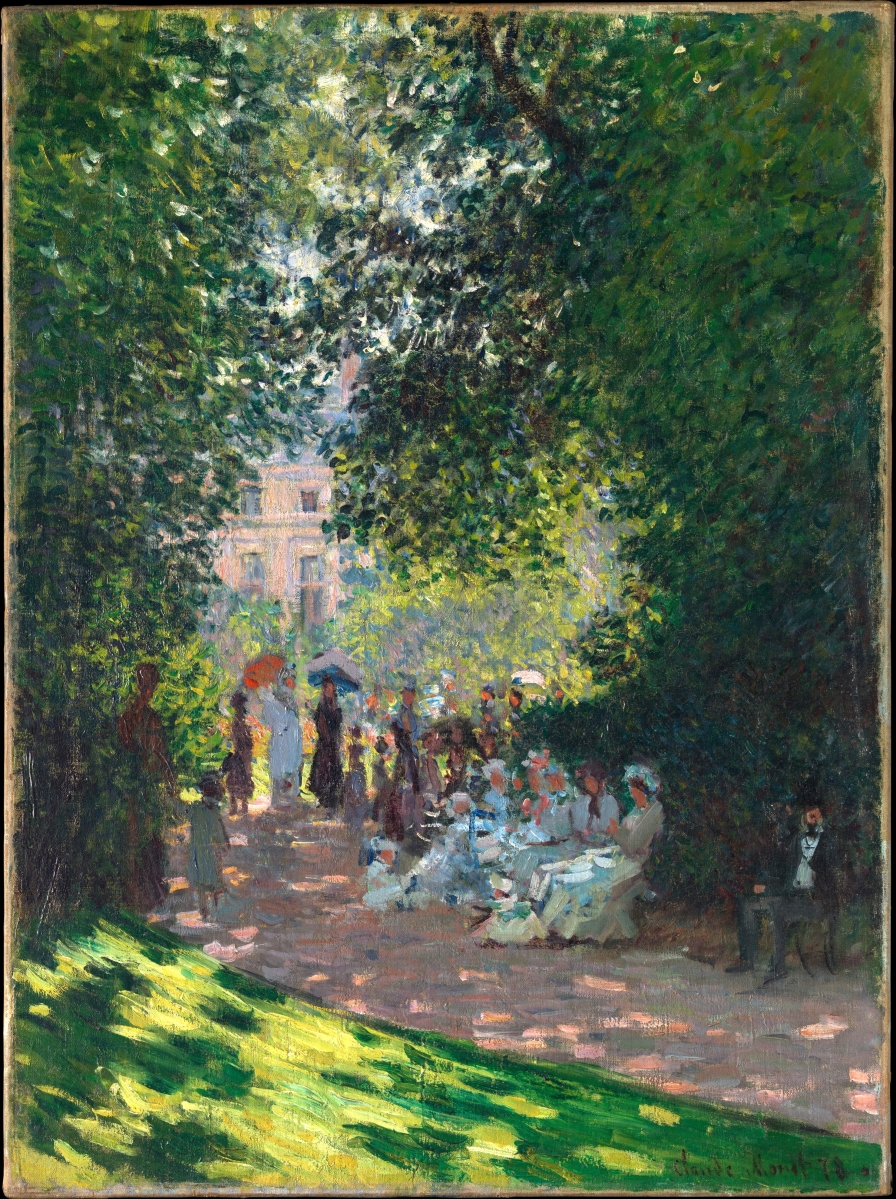

In the late 1860s, Monet began to more regularly visit Paris, ultimately settling there for a time. Monet was drawn to the gleaming, newly redesigned city. Iconic works like “Boulevard des Capucines” show how Monet was striving to be the “painter of modern life” that the writer Charles Baudelaire had described in his work. The elevated viewpoint and the details of crowds milling about a public space are also seen in a series of paintings he completed from a balcony at the Louvre museum. While other artists – including fellow Impressionists Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt – were producing studies of the canonic paintings on view within, Monet was literally “turning his back to the Old Masters,” Daneo says, in order to create his own distinctive view of the modern city.

To flee the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, Monet went first to London and then to the Netherlands, where he was fascinated by both London’s ever-changing fogs and Holland’s bright, marshy openness. He would return to both places throughout his career, but it was London that became a touchstone. “The fog in London assumes all sorts of colors; there are black, brown, yellow, green, purple fogs,” Monet told an interviewer in 1901, “and the interest in painting is to get the objects as seen through all these fogs.” Here we have the idea of using sustained visual engagement, under different conditions, as a way to more fully know a place; here too, we have an explanation for the serial paintings for which Monet became so well known.

After his return to France in 1871, Monet did not return to Paris but for the rest of his life lived in ever-more rural towns in the outskirts. He first settled in Argenteuil, once a rustic retreat from the city but by then ever more of a suburb, thanks to the installation of a train line. Modern life was still a major aspect of the works Monet produced in Argenteuil – the buildings, the bridges, the well-dressed promenaders, even the factories – but he was drawn to the comparatively pastoral aspects of his new home as well. Heinrich sees the early “announcement of a series” in the artist’s recurring theme of heavy-leafed trees reflected in the water of the Seine. These very similar compositions, painted at different times of day, seem, again, a concerted effort to know a place through its many visual moods. He continued with many of the same ideas after moving to the even smaller and more rural Vétheuil. There, the people slowly disappear from his canvases, replaced by an idea of beauty inherent in the most everyday agricultural landscapes – golden wheat fields, a row of rigid green poplars, bright-red poppies applied with just a fleck of pigment – painted over and over again.

These paintings (the later water lilies notwithstanding) are what many of us think of when we think of Monet, and thus we think of them as defining works of Impressionism. But Heinrich argues it’s more complex than that. “I would even discuss whether Monet in his whole work is an Impressionist painter,” he muses. After 1878, he notes, Monet “is pushing the envelope in very different directions,” adding that “this was noted by some of his colleagues, who scold him and say that he becomes a Romantic painter.”

“Fishing Boats” by Claude Monet, 1883. Oil on canvas, 25¾ by 36½ inches. Denver Art Museum, Frederic C. Hamilton Collection, bequeathed to the Denver Art Museum, 37.2017.

Certainly there is a hint of the Romantic in works like “Landscape in the Île-Saint-Martin,” with the rustic path winding invitingly from the viewer’s feet into the interior of the painting. But the sense is even stronger in Monet’s paintings of France’s northern coast, where he increasingly spent more time after he moved to Giverny in 1883. Here are the somewhat prosaic views of fishing boats at their moorings, also a favorite subject of Boudin’s, but here too are sublime scenes of primal nature, with prehistoric-looking rock formations battered by the crashing surf.

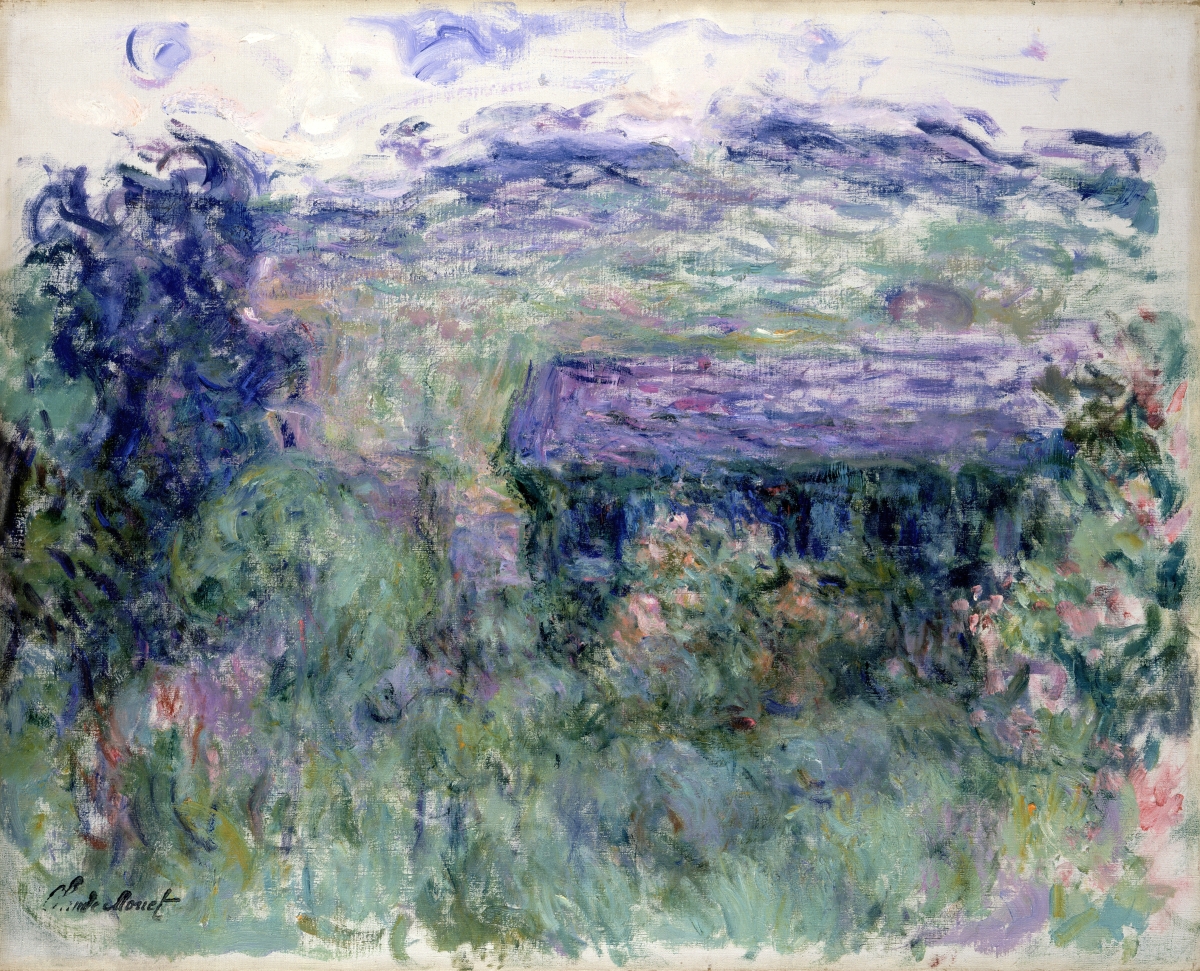

Giverny, where Monet lived out the rest of his days, was even more remote than Vétheuil, and even more of a retreat for the artist. He moved there shortly after the death of his first wife, Camille, and while he already had the companionship of his future wife, Alice. The paintings he produced in Giverny nevertheless have an elegiac tone. Paintings like “Under the Poplars” and “Canoe on the Epte” explore some of the same themes as his earlier paintings, but here there is an increasing simplicity of forms, a reduction to bare elements, a muting of the palette. “Arm of the Seine” and “Morning on the Seine” are so much like scenes from Vétheuil and Argenteuil as to be all but indistinguishable, in terms of marking the specific bend of the river, but their smoky, moody purples and blues make those earlier paintings seem almost shamelessly charming and ornate by comparison.

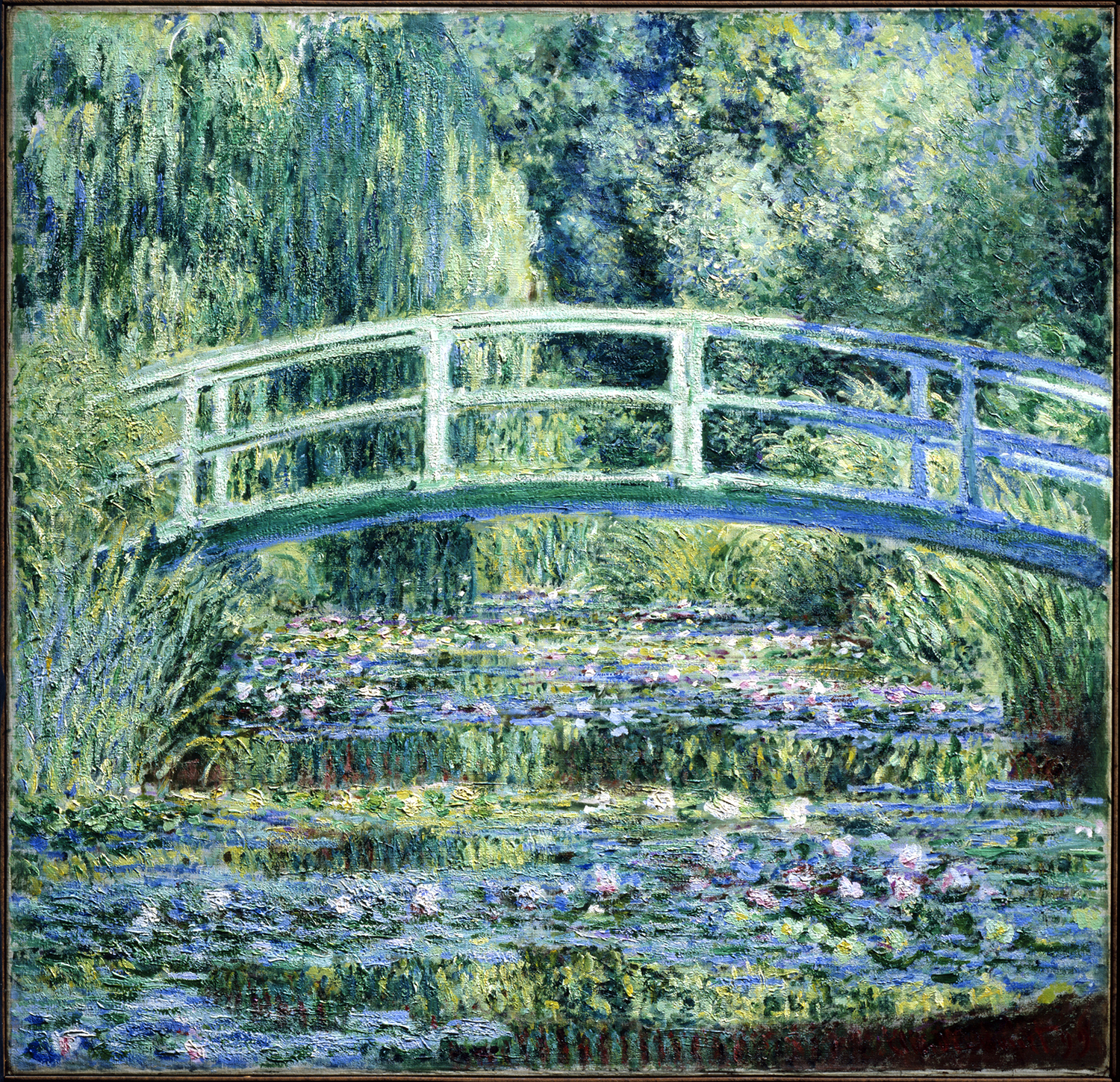

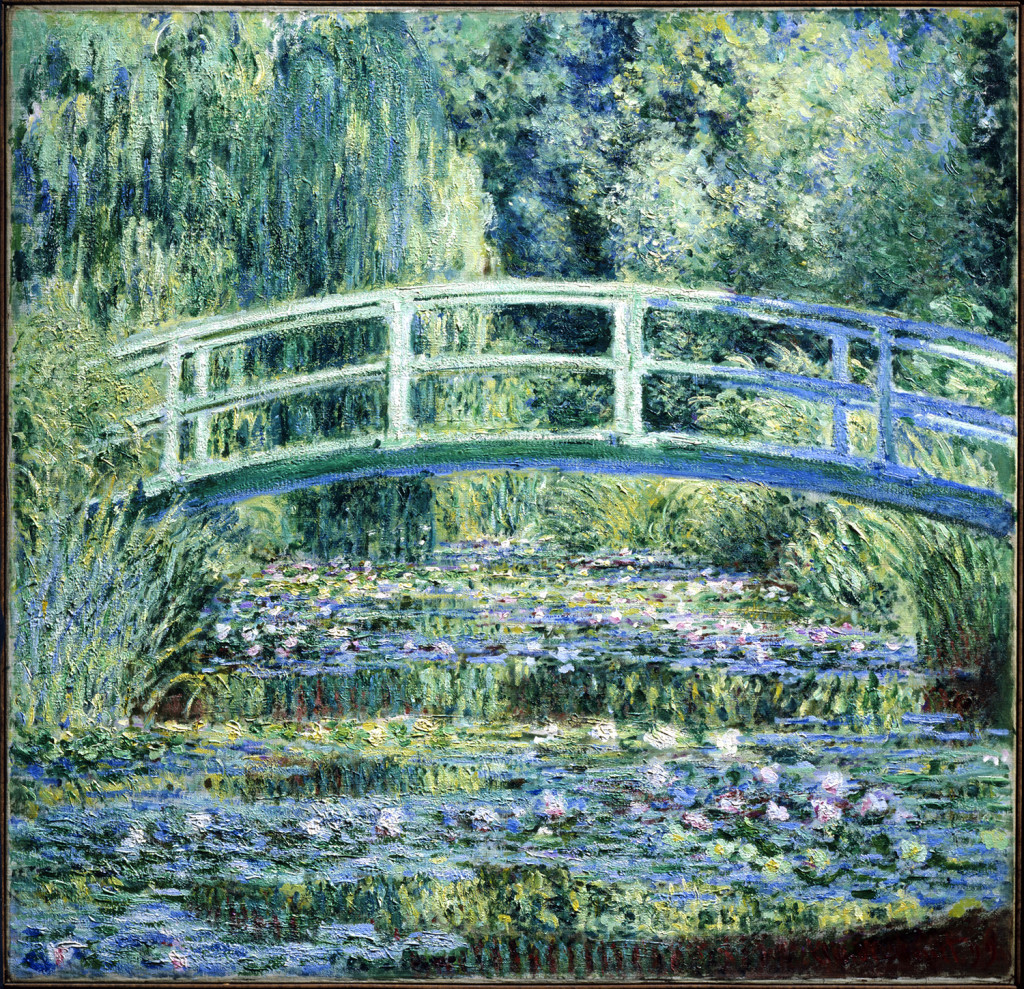

But the later period of Monet’s career was not all about moody meditations. This was also the period when he traveled to the south of France and, later, Venice. His paintings from these travels are often vibrant and joyful, reveling in the unique colors and light of each locale. Over time, through Monet’s efforts, Giverny itself became the same kind of rare and beautiful place. Long a skilled gardener, Monet planted lush flower beds at his new home and also created his now-famous water garden, complete with water lilies and a curved Japanese bridge. Many see the monumental, proto-abstract water lily paintings of the 1910s as the culmination of his career, as well as the fullest expression of his love for his home and garden – but for my money, there is no improving upon “Waterlilies and Japanese Bridge” of 1899, gorgeously reproduced in the catalog. The composition is absurdly simple – austere, even – three horizontal bands of trees, bridge, pond. But it is richly painted and complexly textured, dripping with color and pigment. It’s romantic, if you will – like Ophelia’s watery, flower-bestrewn grave, if that was the first thing you saw every morning, and the thing you painted over and over again every day of your life.

When we talk of Monet’s coming to know a place more deeply through painting it over and over again, we’re talking about knowing it in a visual sense, not necessarily a personal one. Daneo has discussed how, during his travels, Monet mostly just worked and did not do the kinds of things other tourists do to immerse themselves in a place’s culture. But for Giverny it was different. Giverny became a part of Monet, and he of it, uniting the natural world he saw outside his own back door with the image of nature he saw in his mind. For the 43 years that Monet lived at Giverny, he never ran out of things to paint. And so it only follows that scholars, curators and straight-up fans will never run out of new ways to look at and appreciate his expansive body of work.

The Denver Art Museum is at 100 West 24th Avenue Parkway. For more information, 720-865-5000 or www.denverartmuseum.org.