By Laura Beach

BOSTON – What is folk art? We know it when we see it, or think we do, but defining it has long confounded scholars even as the material delights viewers.

Organized by Nonie Gadsden, Katharine Lane Weems senior curator of American decorative arts and sculpture, with assistance from curatorial research associates Sloane Awtrey and Tess Lukey, among others, the exhibition “Collecting Stories: The Invention of Folk Art,” on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) through January 9, 2022, flags the fraught term – the word “invention” is a tip off – before offering thoughts on how collecting perspectives have changed over the past century and where they might evolve from here.

In May 1950, in what it dubbed the “Folk Art Issue,” The Magazine Antiques challenged a panel of well-known experts to define American folk art. “Naïve expression of a deeply felt reality by the unsophisticated American artist,” said Brooklyn Museum curator John I. Baur. “American folk art – the art of the common man – represents the most purely native and the most independent and democratic tradition in American art,” asserted Jean Lipman. Frank O. Spinney, director of the New Hampshire Historical Society, resignedly said he would rely on the inadequate term “non-academic” in lieu of something better. The father of American folk art scholarship, Holger Cahill, dodged the question altogether, opining, “So far as a definition of folk art is concerned it is my belief that the material will define itself if one will allow it to do so.”

The conundrum has only deepened. Writing in the Winterthur Portfolio in 1980, John Michael Vlach blasted scholars, saying, “Fifty years after the first major recognition of the subject at the Newark Museum, the field still lacks a consensus definition, a workable set of evaluative criteria, and a tenable theoretical framework….While the study of academic art in Western society or the art of so-called primitive peoples has progressed remarkably, considerations of folk art continue to be tied to a joyous manifesto of 1930s discovery.”

Shifting horizons made the topic a timely one for the MFA’s “Collecting Stories” project. The introspective series of one-year displays funded by the Henry Luce Foundation plumbs the mutable nature of taste as revealed by understudied or underserved aspects of the MFA’s permanent collection. The third and final presentation of the series, “The Invention of Folk Art” follows “A Mid-Century Experiment,” assessing the MFA’s first tentative embrace of Modern painting, and “Native American Art,” which delved into Brahmin Boston’s attitudes toward indigenous art at the turn of the last century.

“The intent of ‘Collecting Stories’ was to explore new narratives in American art and the formation of American identities, an ambition that fit perfectly with what we were already trying to do in the MFA’s Art of the Americas department. The funding included money for research, conservation and mounting the exhibitions, as well as the opportunity to hire an emerging scholar in the field and four summer interns of diverse backgrounds. In many ways it was a curator’s dream. These shows have been about the conscious and unconscious choices collectors make and the prejudices of different eras,” Gadsden said recently by phone.

For the present display, Gadsden chose 59 works on paper, to be shown in two rotations, and 20 sculptural objects. Most were collected by Maxim Karolik (1893-1963), a Russian immigrant who married the Boston-born society figure Martha Codman (1858-1948). In what Karolik called their “Trilogy,” the couple built and donated to the MFA two major collections: the first, in the 1930s, consisted of American decorative arts; the second, in the 1940s, of American paintings. Karolik completed the third collection – focusing on American watercolors and drawings, both academic and folk, but including some folk sculpture – after his spouse’s death.

“Sarah Ann Drew” by Ruth Whittier Shute (1803-1882), about 1827. Watercolor, pen and black ink, graphite pencil on paper. Gift of Maxim Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Watercolors and Drawings, 1800-1875.

“Karolik was one of the first to try to integrate folk art into an encyclopedic art museum. In some ways an outsider himself, he saw no difference between ‘folk’ and ‘fine,'” says the curator. Karolik’s embrace of folk art on behalf of the museum intensified in August 1948 after attending the Berkshire Hills Antique[s] Show, organized by Flora Campbell Koones. In what he called his “Lenox episode,” Karolik bought more than 80 folk art works on paper at the fair, then telephoned MFA curator of prints Henry P. Rossiter (1885-1976), with whom he was collaborating, to tell him of his triumph. Receipts in the Karolik archives at the Massachusetts Historical Society document purchases from Clifton Blake, Louis Lyons, Robert Schuyler Tompkins, Addie Perry and Helene Mitchell.

“The Invention of Folk Art” is the third major presentation of the Karolik folk art collection, the foundation of the museum’s holdings in the category, at the MFA in 60 years. Because of their light-sensitivity, works on paper are the least shown. More than 2,000 people attended the opening of “The M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Watercolors and Drawings, 1800-1875” on October 17, 1962. The trove was featured again in the 2001 MFA exhibition, “American Folk,” organized by Carol Troyen and Gerald W.R. Ward.

“The Invention of Folk Art” kicks off the MFA’s multi-year Folk Art Initiative. As Gadsden explains, “Folk art is a category of American art invented, and continually reinvented, by modern artists, collectors, dealers, curators and art historians over the past century. In reality, the changing definitions of ‘folk art’ reveal more about the values, needs and desires of the community doing the defining than about the individual artworks themselves.”

“Army Signalman” whirligig by John Green Satterley (1820-1882), about 1865-70. Painted wood. Gift of Maxim Karolik.

Installed in the Edward and Nancy Roberts Family Gallery in the MFA’s Art of the Americas Wing, the show opens with an overview of the field’s beginnings, noting the popularizing influence of early Modernists such as Marsden Hartley and Charles Sheeler, who “admired the graphic silhouettes, flattened perspective, bold color contrasts and exaggerated proportions they found in the work of nonacademically trained painters, hobbyists and skilled artisans, including woodcarvers, metalworkers and sign painters.” A circa 1890-1900 wrought iron boot scraper in the form of a rooster, discovered in Pennsylvania and purchased from Adele Earnest’s Stony Point Folk Art Gallery, and Ruth Whittier Shute’s (1803-1882) top-heavy portrait of Sarah Ann Drew speak to such Modernist sensibilities. Karolik’s efforts to bring folk art to the MFA, his collecting philosophy, and sources and collaborators, among them the estate of Elie Nadelman and Edith Halpert, are also considered.

From there the presentation moves to Karolik’s “Art of the People” and the collector’s wish, in his own words, to “reveal, through art, the heartbeat of a nation.” Material prosperity associated with expanding transportation networks and burgeoning consumer markets in Nineteenth Century America opened avenues of expression to ordinary citizens, from itinerants and hobbyists to women and the rural poor, resulting in the democratization of art.

“Although Karolik sought to expand the definitions of art, he was more interested in the aesthetic and less interested in the diversity of voices behind it. By contrast, scholars today are more attentive to the social context of creation. We’ve engaged in some myth-busting of the concept of the self-taught genius and look at the correlation between the rise in visual culture and the rise in folk art. We’ve found the sources that inspired many of the works in the Karolik collection,” says the curator, pointing to sandpaper – or, more accurately, marble-dust – drawings, silhouettes and theorem paintings as examples of popular artforms influenced by print prototypes. In one revealing pairing, a hand colored lithograph of “Lake Ontario, New York” after Jasper Francis Cropsey (1823-1900) is shown with a pastel and graphite rendering by an anonymous artist clearly familiar with the Cropsey prototype.

Scaup hen decoy by A. Elmer Crowell (1862-1952), early Twentieth Century. Wood, paint. Gift of Maxim Karolik.

The stand-alone section “So Many Stories” examines three objects from multiple perspectives. “It’s a 360-degree approach, from looking at who the artist was, the historical context, the subject matter, the materials and technique, the donor and collector, the contemporary context, and artist and scholar responses,” says Gadsden. As an example, the silhouette papercut “Our President, Old Hickory (President Andrew Jackson)” by James Hosley Whitcomb (1806-1849) depicts a figure now reviled for his racist views and policies. “The image meant something different when it was made in 1830 and then when Karolik collected it more than a century later. And our contemporary eyes see it very differently today,” the curator says.

In the show’s final section, Gadsden reckons with the deficiencies and prejudices of folk art collecting in the mid-Twentieth Century. Acknowledging the scarcity of works by Black, Latinx and other under-represented communities in the Karolik collection, the curator includes more recent MFA acquisitions. Among them are a stoneware face jug made at the Thomas Davies Pottery in South Carolina’s Edgefield District around 1860 and “Untitled (Black and White Frontal Caballero),” a graphite, ink and colored pencil on paper drawing by the visionary artist Martin Ramírez (1895-1963), the latter to be included in the second rotation.

Gadsden notes, “We acquired two major pieces of vernacular art in the past year. One is a circa 1820s tall case clock, with works by Silas Hoadley (1786-1870) of Connecticut and a smoke-decorated case, probably from Maine, that looks extraordinarily modern. The other, the ‘Battleship Kate,’ a trade figure from about 1935, features tattoos by one of the most renowned American tattoo artists, August ‘Cap’ Coleman of Norfolk, Va.” The figure surfaced at the Heart of Country antiques show in the mid-1980s and passed through several owners before authority Derin Bray sold it to the MFA in 2020.

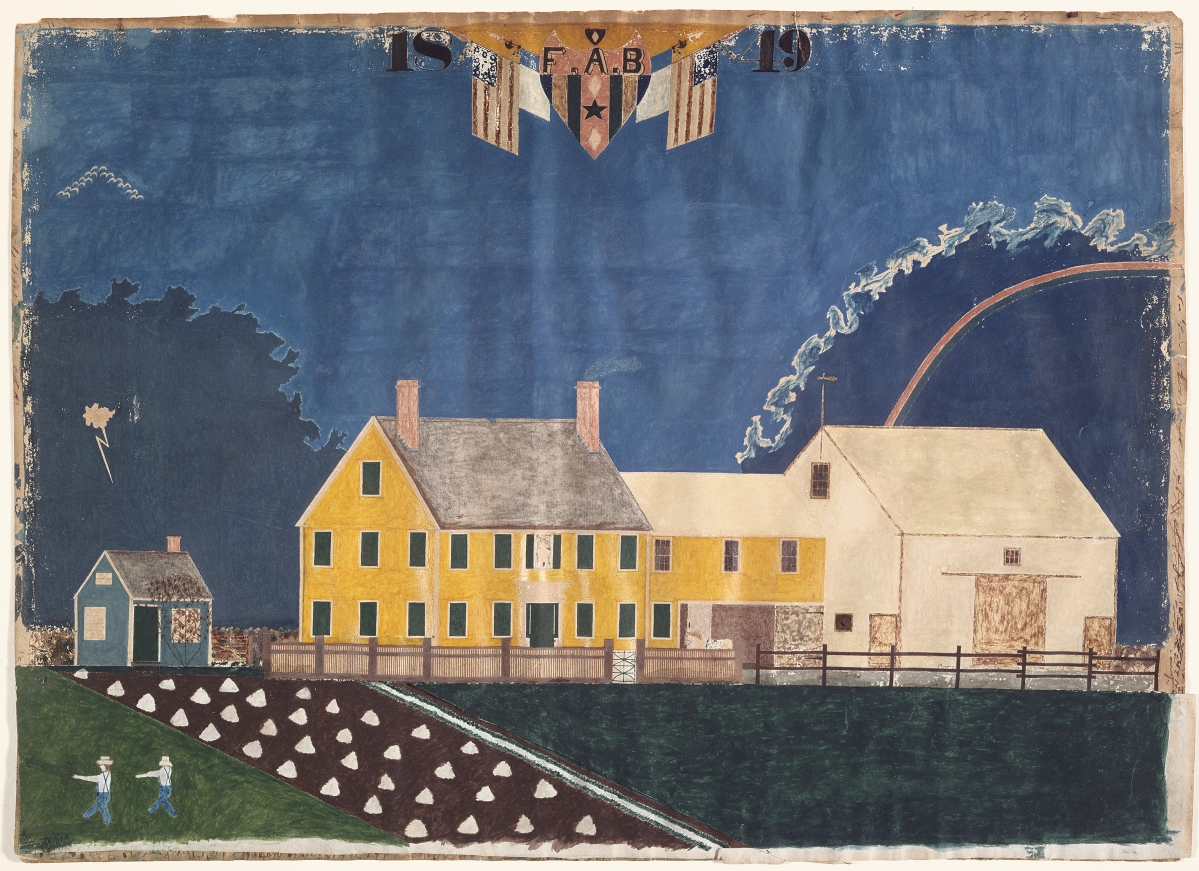

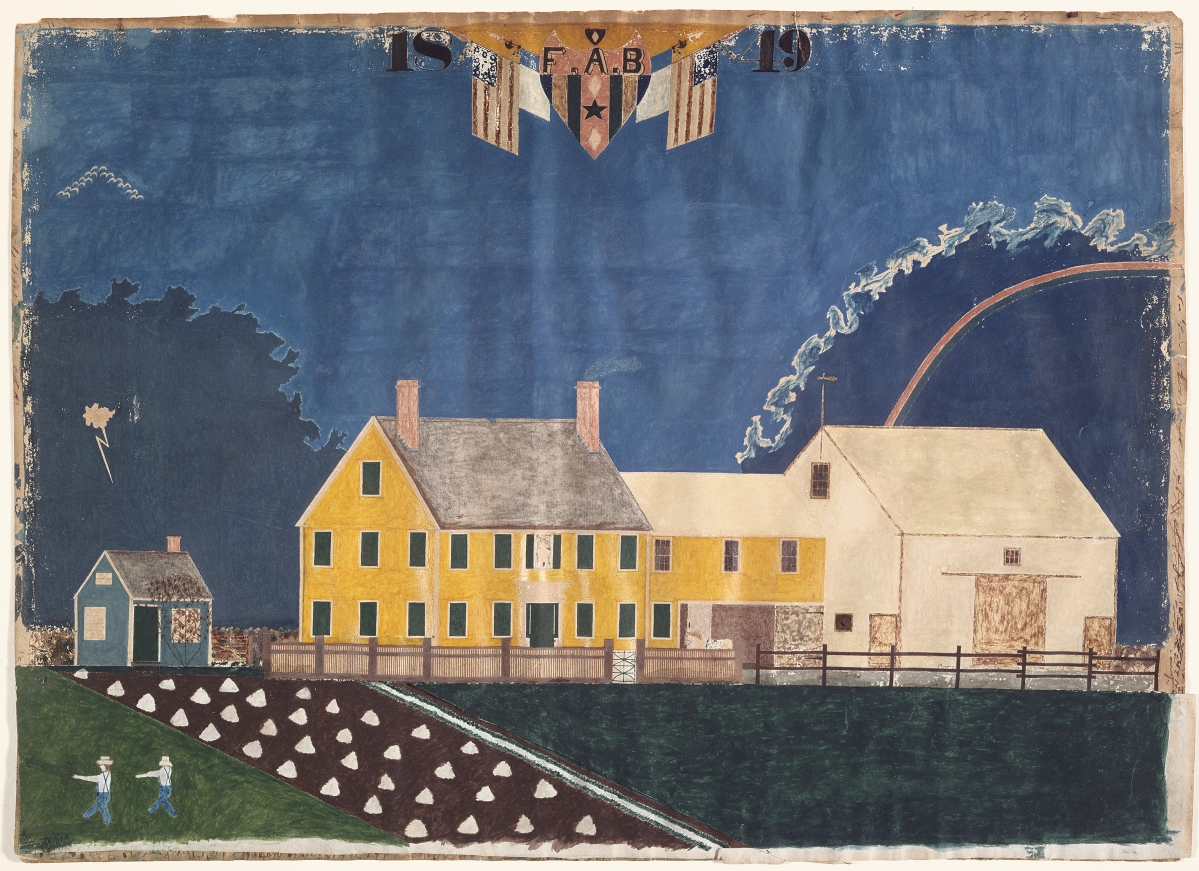

“Farmstead in Passing Storm,” unidentified artist, 1849. Opaque watercolor, tempera, graphite pencil and pen and brown ink with collage on paper. Gift of Maxim Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Watercolors and Drawings, 1800-1875.

“It’s a fantastic piece to signal our new thinking. Coleman reused an earlier trade figure based on ‘The Greek Slave,’ the most famous American sculpture of the Nineteenth Century. When Coleman tattooed the figure from neckline to toe, he gave it a whole different life, questioning the definitions of art in the process,” Gadsden explains.

“Collecting Stories: The Invention of Folk Art” initiates a long overdue cultural reckoning at the MFA. Gadsden asks, “We want visitors to think about what makes something ‘art.’ My hope is not to replace the term ‘folk art’ with something else, but eventually eliminate the term. We are not there yet, but bringing attention to the history, the questions and the concerns is a first step.”

Dealers, collectors and scholars will continue searching for better ways to describe and evaluate non-academic American art. Whatever we call this unscripted expression, viewers respond viscerally to its authenticity and immediacy. “Its power to engage is something my colleagues and I would love to get to the crux of and to harness in productive ways,” Gadsden says.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is at the Avenue of the Arts, 465 Huntington Avenue. For more information, 617-267-9300 or www.mfa.org.

All objects are from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All photographs are © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)