“Factories at Clichy” by Vincent van Gogh, 1887. Saint Louis Art Museum, Funds given by Mrs Mark C. Steinberg by exchange.

By James D. Balestrieri

CHICAGO — Those moments when events — and people — come together in fruitful, fortuitous combinations — moments we file under the heading “serendipity” or “providence” — often elude our attention until later, looking back, in that hindsight we call 20/20, when we say the “stars aligned” and came together in conjunction. Clichés aside, history is made in such moments. In the history of art, however, they are, or at least seem, less common and are all the more remarkable when they arise.

Spring, 1887.

Five Neo-Impressionist masters cross paths in the Parisian suburb of Asnières. They observed, adopt, adapt and sometimes ultimately reject one another’s facture. Of the five, two are household names: Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), and Georges Seurat (1859-1891), while the other three, Paul Signac (1863-1935), Emile Bernard (1868-1941) and Charles Angrand (1854-1926), each in his own way, make significant contributions to what we have come to regard as modern painting. Envision this town across the Seine as we do a suburb — one that can be reached by train — and Asnières turns out to be a destination for Seurat and Signac, a detour for Bernard and Angrand, and a critical way station for Van Gogh as he was passing through from Paris to Arles. “Van Gogh and the Avant-Garde Along the Seine,” a collaborative effort between the Art Institute of Chicago and the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam — now on view in Chicago through September 4 — sheds new light on this brief but critical few months. A broad and deep selection of works and meticulous scholarship allow us to watch as the artists react and innovate and as the styles of all five evolve.

But these first Parisian suburbs weren’t exactly the suburbs we know. “Le nouveau Paris” as conceived in Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte’s reign, first as president (1848-52) and then as Emperor Napoleon III (1852-70), not only saw Medieval Paris razed; it also saw the ancient city replaced with boulevards, railroads and sewers. Georges-Eugène Haussmann oversaw the transformation: new “Haussmannian” apartment buildings went up; gas lamps lit the boulevards; trees once again lined the streets. The Second Empire lent its name to the style that arose from the modernization campaign. As a result, as Jacquelyn N. Coutré’s essay in the catalog states, some 350,000 people, largely from the lower and working classes, were forced to relocate to the suburbs. The factories that employed these Parisians moved with them. But trains ran between the heart of Paris and Asnières and other nearby suburbs, and soon, on Sundays, it became fashionable to go boating and rowing, fishing, strolling and loafing along the suburban Seine. Quayside clubs and restaurants sprang up to meet the demand. For artists like Van Gogh, Seurat and the others, the environs ranged across natural landscapes, industrial sites, recently fabricated dwellings, and loci of leisure while the people were a heady mix of the poor, the working classes and the nouveau riche — at least on Sundays. From overtly political works to paintings of pure aesthetic formality, the Asnières Five produced reams of studies and finished works, taking advantage of this pageant of novelty to distinguish themselves from Monet and the first generation of Impressionists.

“Iron Bridges at Asnières” by Emile Bernard, 1887. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Grace Rainey Rogers Fund.

Though Van Gogh is clearly the center of the exhibition, it’s worthwhile spending some time with the other four painters to get a sense of the energy of the moment. If we can say, roughly, that the Impressionists freed painting from the academic reliance on line, and line drawing as the underpinning of good painting, and that, further, light and color assumed the primary roles in their practice, the Neo-Impressionists sought to organize light and color, to reformulate and reformalize it. Divisionism has more to do with the science of color theory, where the artist relies on the viewer’s eye to “mix” adjacent colors, and employs patterns of longer, almost cube-like brushstrokes, often painted in parallel. Pointillism, on the other hand, has more to do with painting in an arrangement of dots of pigment in patterns to delineate forms.

Seurat, who might be said to be the father of Pointillism, discovered the suburbs early in the 1880s, concentrating his energies on the Sunday strollers, boaters and anglers on La Grand Jatte, an island in the Seine not far from Asnières that would become the setting of his most famous painting, “A Sunday on La Grande Jatte” (1884-86), or, as Stephen Sondheim deemed it, Sunday in the Park with George.

A study for “La Grande Jatte, Woman Walking with a Parasol,” dated 1884, shows us Seurat’s rejection of the naturalism, as it were, in Impressionism. Seurat’s figures have what has been called a “doll-like,” mannequin stiffness, perhaps an allusion to the buttoned-up formality of the age. Here, little if anything distinguishes the woman as an individual. She seems to represent a social class, wearing a costume and manner that shields identity. What is most interesting, perhaps, is the effect of the conte crayon on the woven paper. Dots in vertical and horizontal rows pixilate the drawing. It is at once Divisionist and Pointillist. One wonders if Seurat’s Neo-Impressionist version of paint application arose from his drawing practice, a practice that would have compelled him to eliminate detail and focus on mass while at the same time revealing his “dot matrix” personal style.

“The Restaurant Rispal at Asnières” by Vincent van Gogh, 1887. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Mo., Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch. Photo courtesy Nelson-Atkins Media Services, Jamison Miller.

Charles Angrand’s “The Seine at Corbevoie, La Grand Jatte,” painted in 1888 — perhaps easel-by-easel with Seurat, who also painted in very nearly the same spot at the same time of the same year — is a meditative work, at once Divisionist and Pointillist, relying on the juxtapositions of contrasting colors to create the illusion of depth yet keeping the strokes relatively small. In later paintings, Angrand would play with the size of his brushstrokes, reducing them to the blizzard some of us remember on our old televisions, before abandoning painting altogether — for reasons unknown, the catalog suggests — in favor of monochromatic conté crayon portraits and drawings.

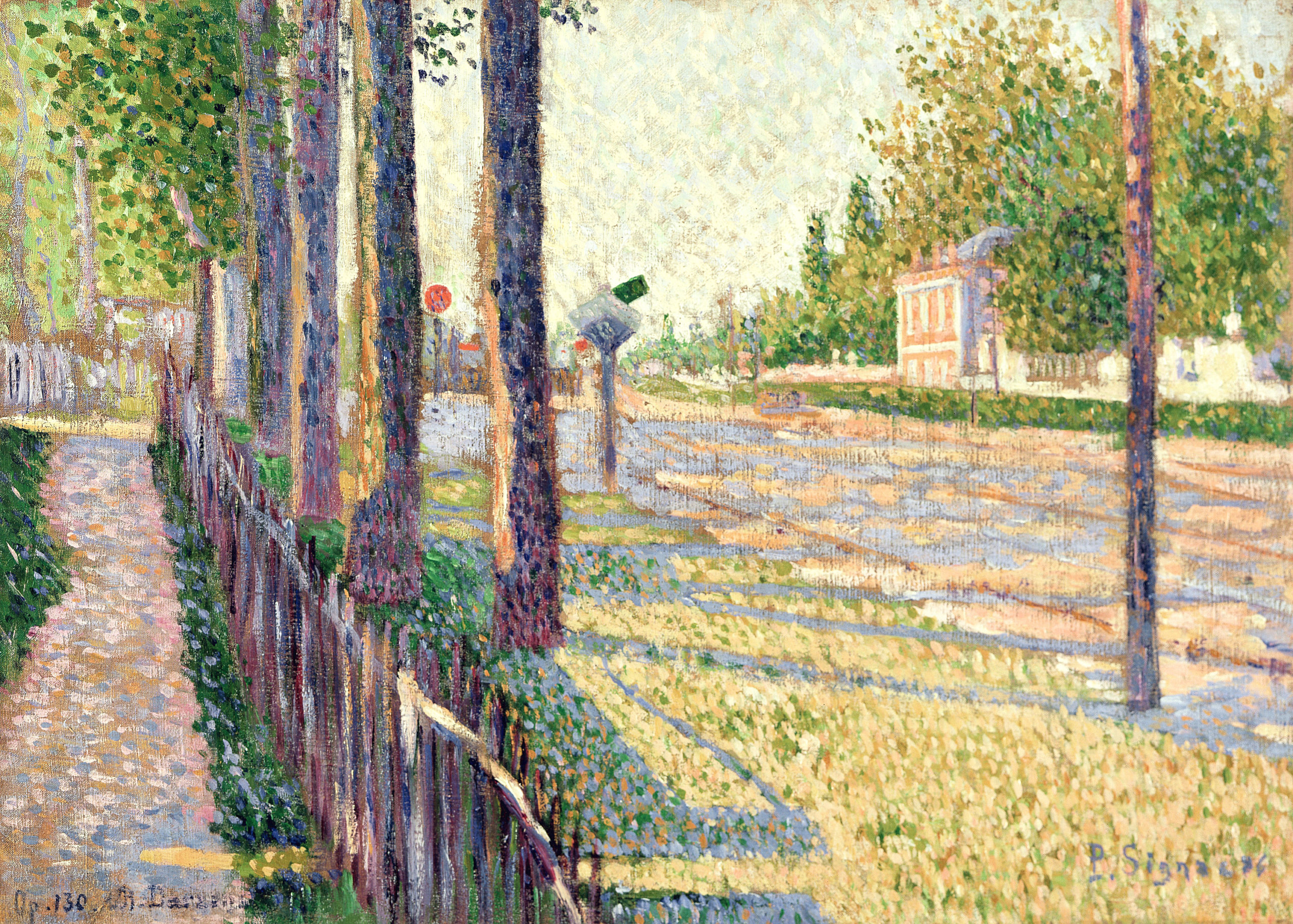

Paul Signac, who had the longest life of any of the Asnières Five, embraced Seurat’s Pointillism enthusiastically in the suburbs of Paris, taking it with him to the south of France, where he spent the majority of his career. An 1886 painting, “Gasometers at Clichy,” reveals a scene from Asnières’ heavily industrialized neighbor, the suburb of Clichy. At this early stage, Signac strives to extract rhythms from the scene and find a style to match them.

The gasometers were storage tanks for the fuel that lit Paris. They were new, scientific, and the general attitude of the era was that science and industry signaled progress, and that progress would be the salvation of mankind. We have to be careful here not to impose our knowledge of the perils of fossil fuels and the climate catastrophe onto Signac’s painting. Still, Signac shows us the makeshift buildings, hastily erected fence, and barren, half-green, half-gray ground between the impressive gasometers at left and right. If this is progress, there is nevertheless a subliminal aspect of the painting indicating haste that might come with a cost to nature and to humanity.

“The Seine at Courbevoie” by Georges Seurat, 1885. Private collection.

Emile Bernard dabbled in the dots and dashes of Pointillism and Divisionism. And before you dismiss my metaphor of the dots and dashes of Morse code as droll, remember that the telegraph was a recently invented wonder of the world then, and the influence of its graphic expression — dots and dashes — on the arts is one that might be taken into account. Bernard, however, moved to a style called Cloisonnism, after the Japanese prints and porcelain designs that took the French art world by storm. In Cloisonnism, thick, monochromatic, calligraphic outlines delineate shapes while color is applied inside the lines, with appropriate shading, textures and so on. Painted in 1887, “Two Women on the Asnières Footbridge” and “Iron Bridges at Asnières” reveal Bernard’s interest in the new, industrial France, the working class, and — in the upturned sculls for example, his acknowledgement of the leisure class, who would only visit on the weekends. Cloisonnism gets us to Toulouse-Lautrec and to the Art Nouveau poster movement.

Van Gogh took all of this in. From the few letters he wrote in the period — he was living with his brother Theo, so there was no need for correspondence — he wanted to move away from grays and browns, the Dutch palette that influenced the beginning of his career, and was taken by the Neo-Impressionists’ bold approach to color. He painted flowers, forests, restaurants, boats on the Seine, factories and people moving through this new, liminal space. He experimented with Divisionism and Pointillism, at times combining them in a single picture. Van Gogh collected and even exhibited his Japanese woodblock prints, but though there are hints of the calligraphy of Cloisonnism in his work, he did not employ the heavy outlines that characterize Bernard’s painting.

“The Railway Junction at Bois-Colombes (Opus no. 130)” by Paul Signac, 1886. Leeds City Art Galleries.

The restlessness of the suburb of Asnières matched and suited Van Gogh’s own temperament in 1887. He was passing through, but he wasn’t sure which train to take or which track it would be on. Compare the almost uncontrolled chaos of “Riverbank in Springtime,” a panel from one of two triptychs reunited in the exhibition, with the strict control of the dots and dashes in “Outskirts of Paris: Road with Peasant Shouldering a Spade.” Then consider the freedom in Van Gogh’s mind, eye and hand in “The Bridge at Courbevoie” and “The Laundry Boat on the Seine at Asnières.” Arabesques, rhythmic strokes and a fearless palette turn the Seine a goldenrod color and make the anchor and other elements in the “Laundry Boat” blood red. “Smokestacks in Factories at Clichy,” displacing the steeples that once pierced the sky, are a rhythm of wind instruments, sending clouds of musical notes or murmurations of starlings into the air. But it’s a seemingly simple painting like “Exterior of a Restaurant in Asnières,” with its golden sheen, subtle textures, fast, calligraphic drawing, and just a hint of disregard for perspective that conducts Van Gogh to the right track and train, the one heading south, to Arles.

The function of “Conjunction Junction” in the classic television show Schoolhouse Rock is to show how little words are crucial to making the proper connections. In the liminal space, the threshold that was Asnières, Van Gogh put the dots and dashes of Neo-Impressionism together until the timetable told him it was time to dash and create his own language. I’m aware that I’ve mixed metaphors and cultural landmarks here — quite shamelessly, in fact — but exactly in the way that Van Gogh and the rest of the Asnières Five mixed styles and techniques. And only so you won’t forget to see “Van Gogh and the Avant-Garde Along the Seine.”

“Van Gogh and the Avant-Garde Along the Seine” is on view at the Art Institute of Chicago through September 4.

The Art Institute of Chicago is at 111 South Michigan Avenue. For information, www.artic.edu.