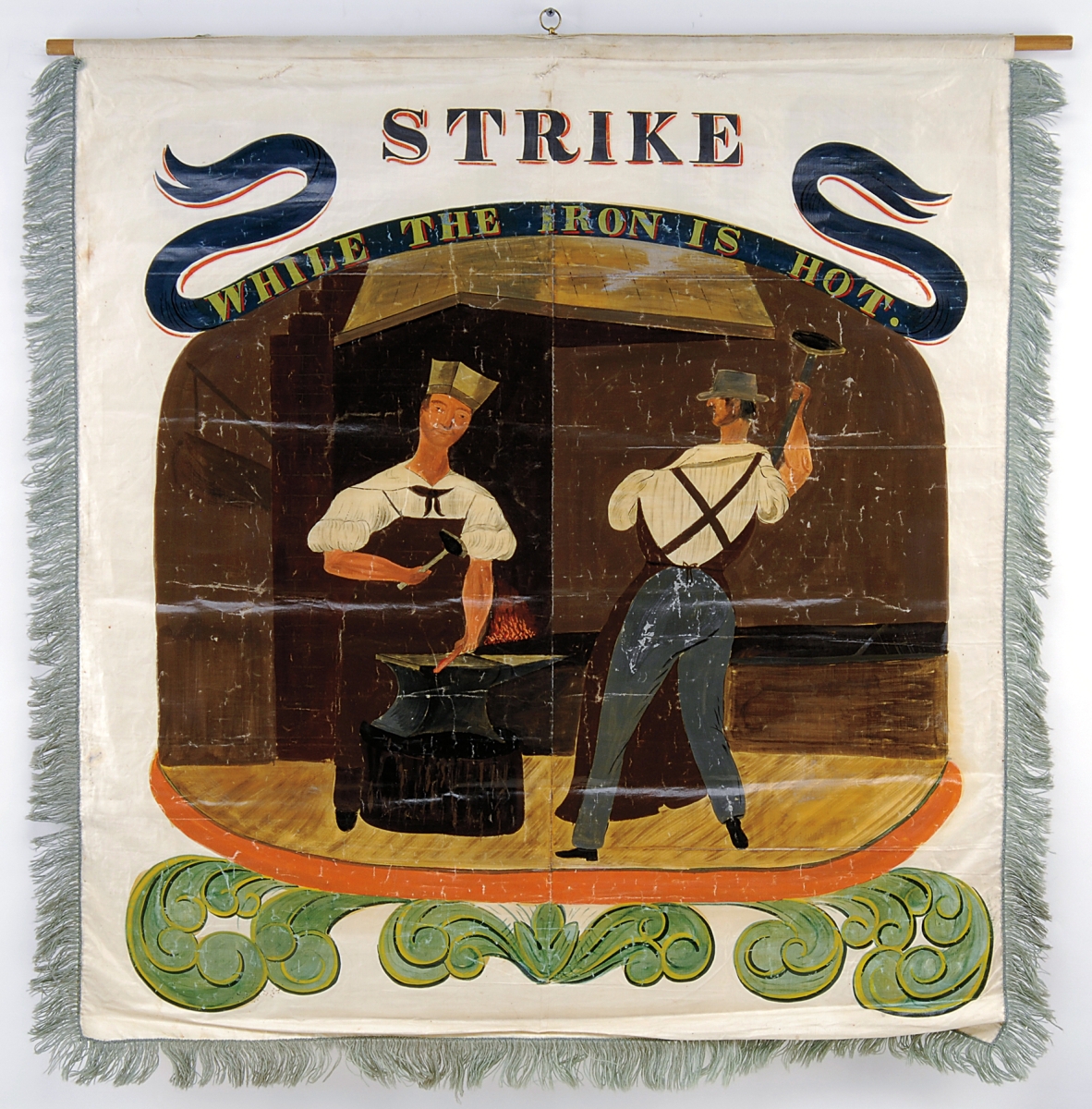

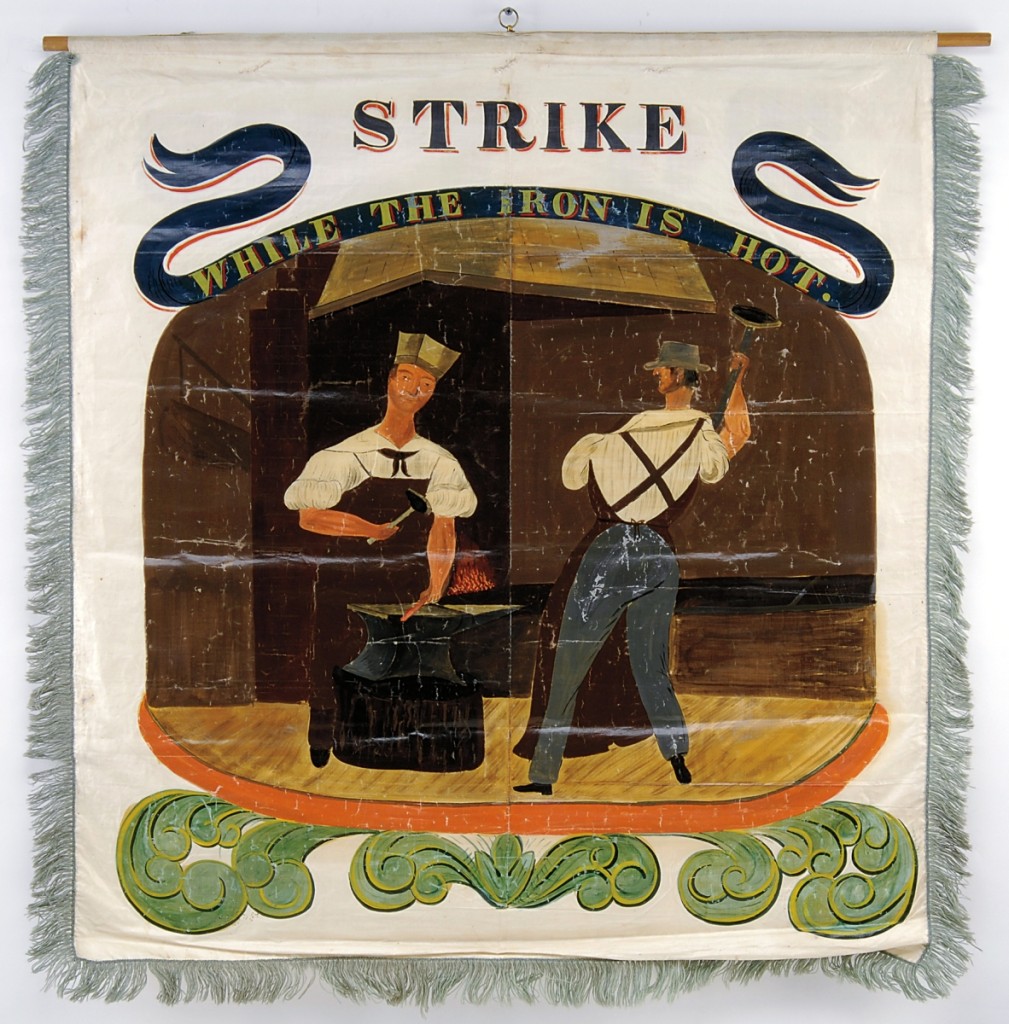

The reverse reads, “To This are All Indebted” and includes an image of a raised arm holding a hammer — not unlike the longstanding logo of the Maine Charitable Mechanic Association, worked in mosaic in the front entry of its 1859 building. Blacksmiths banner by Joseph E. Hodgkins.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

PORTLAND, MAINE – Seven years ago this summer, the Maine museum world was in turmoil. In July, the Portland Press Herald reported that 17 rare, hand painted trade banners owned by the Maine Charitable Mechanic Association (MCMA) were headed for the auction block, likely to be sold out of state and/or broken up as a collection. MCMA’s then-president was sympathetic to the community’s concerns, but maintained that the sale was necessary in order to support the care of the Mechanics’ historic building, which he described as both its greatest asset and its greatest liability. The controversy was covered widely, including in The New York Times.

When help came, it was not in the form of just one guardian angel, but many. Portland’s Maine Historical Society (MHS), which as MCMA’s neighbor on Congress Street had served as the banners’ sometime steward since the 1980s, convinced a small army of Maine museums to pool their resources and bid on the banners collectively.

Those committing funds included not only MHS, Maine State Museum, Maine Maritime Museum, Portland Museum of Art and the museums at Bowdoin, Bates and Colby Colleges, but also the Maine Historic Preservation Commission, individual donors and corporations and foundations from inside and outside of Maine. The auctioneer, James D. Julia, did his part by creating incentives for the banners to be auctioned off as a single lot.

Still, no one knew what would happen on the fateful day, with tense negotiations going on behind the scenes between Maine Historical Society and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which was also intensely interested in the banners. By summer’s end, however, the news was nothing but good. The banners had been saved. Thanks to what MHS’s then-director Richard D’Abate called the “focus, hard work and unselfish generosity of the cooperating museums,” they now belonged outright and in full to MHS.

Still, no one knew what would happen on the fateful day, with tense negotiations going on behind the scenes between Maine Historical Society and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which was also intensely interested in the banners. By summer’s end, however, the news was nothing but good. The banners had been saved. Thanks to what MHS’s then-director Richard D’Abate called the “focus, hard work and unselfish generosity of the cooperating museums,” they now belonged outright and in full to MHS.

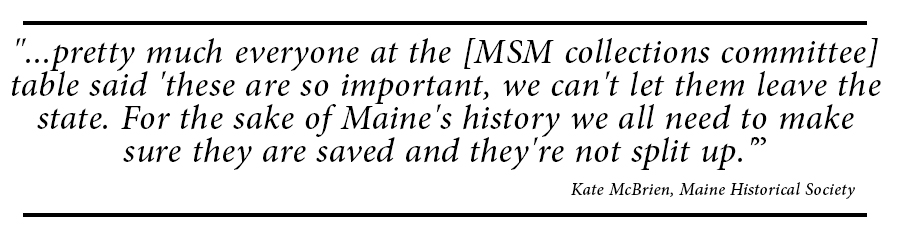

MHS curator Kate McBrien has a unique perspective on this backstory, since she was a curator at the Maine State Museum when all of this was going on. Her memory is that “pretty much everyone at the [MSM collections committee] table said ‘these are so important, we can’t let them leave the state. For the sake of Maine’s history we all need to make sure they are saved and they’re not split up.’ The incentive of preserving Maine’s cultural history, even if it meant committing limited acquisition funds to another museum’s collection, was its own reward. However, it was also understood that participating organizations would receive full recognition whenever the banners were exhibited – which indeed they have been in ‘Creative Maine.'”

Members of the consortium are free to borrow the banners for their own exhibition initiatives. To date, both Colby and Bowdoin have made requests.

To make good on those promises, MHS had to conserve the banners and make them display- and travel-ready. Enter Gwen Spicer, a textiles conservator known for her work with historic flags and banners. In her upstate New York studio, Spicer cleaned and stabilized each three-by-four-foot banner over a period of several years. In the weeks before the exhibition opened, McBrien invited me to see the conserved banners, by then back in MHS’s storage facility. Seeing them in person, after reading about them over a period of years, was revelatory.

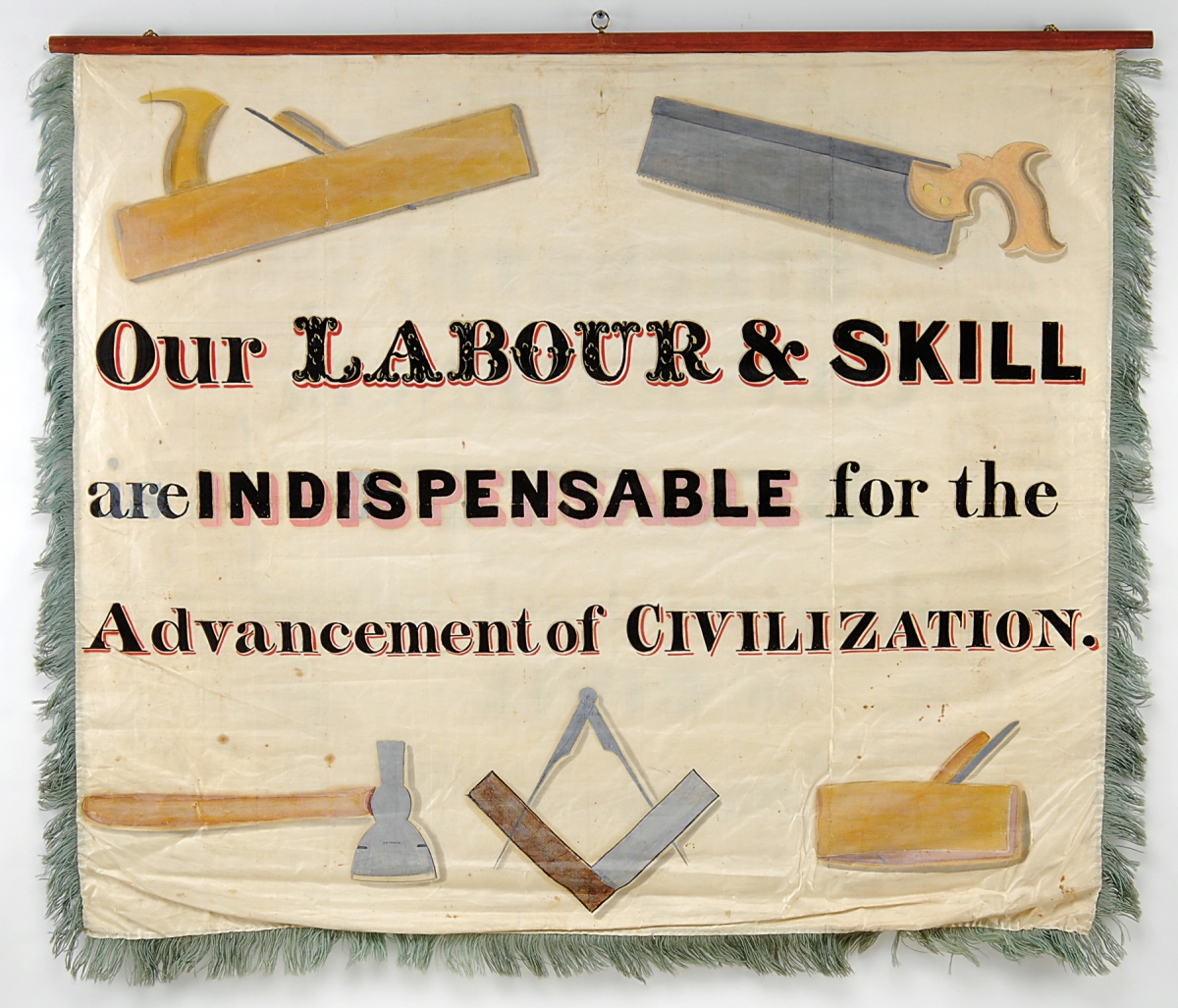

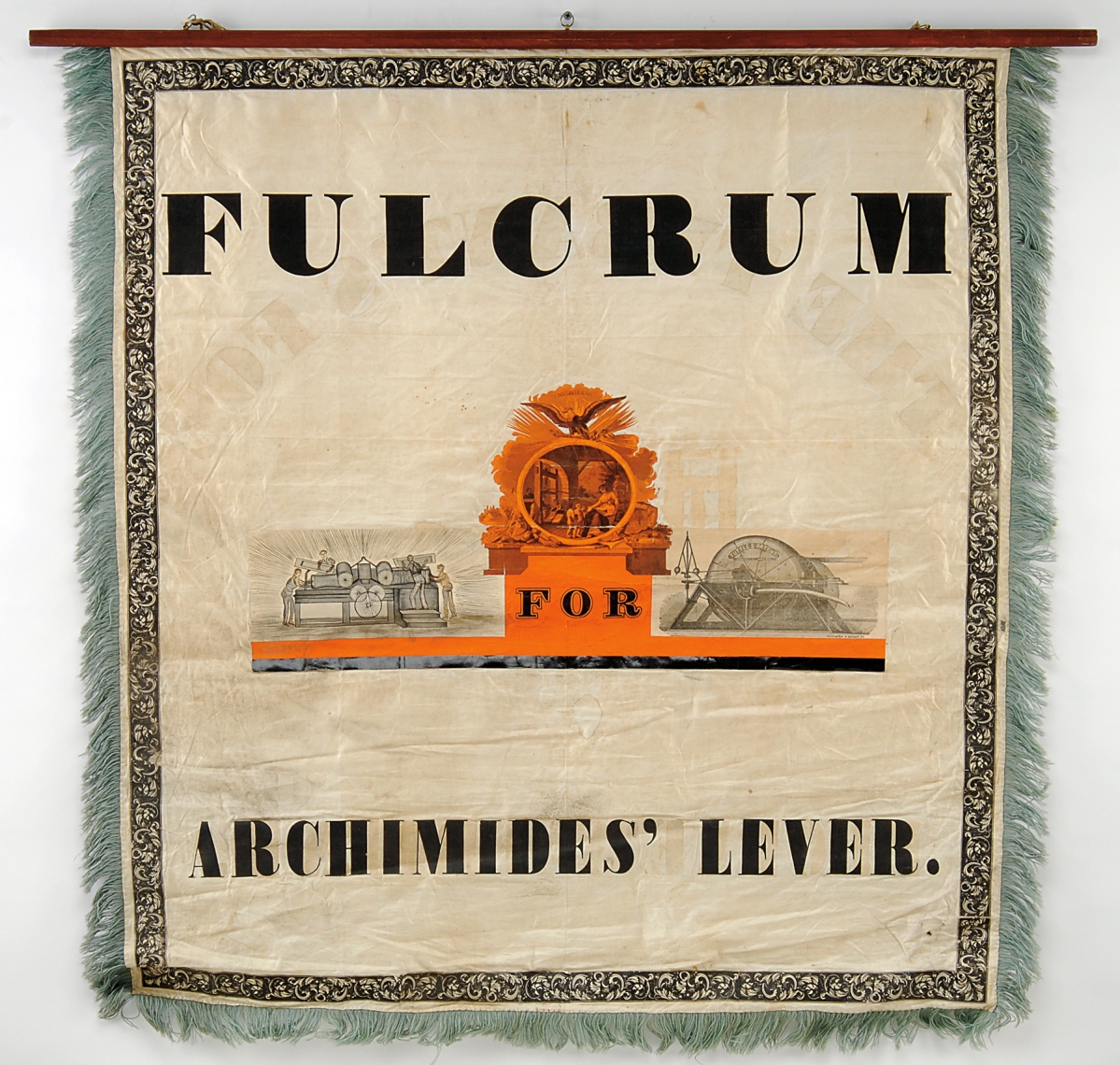

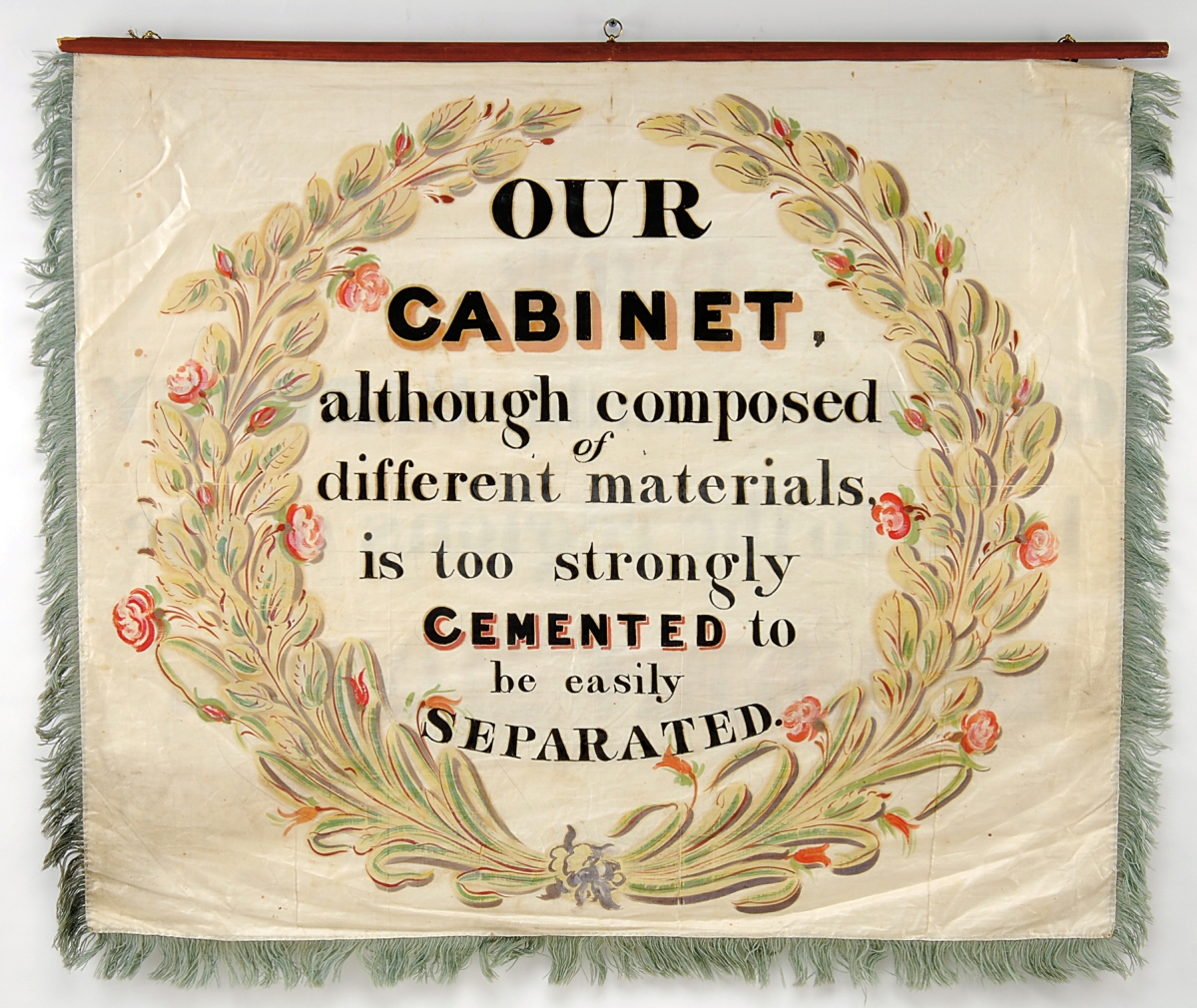

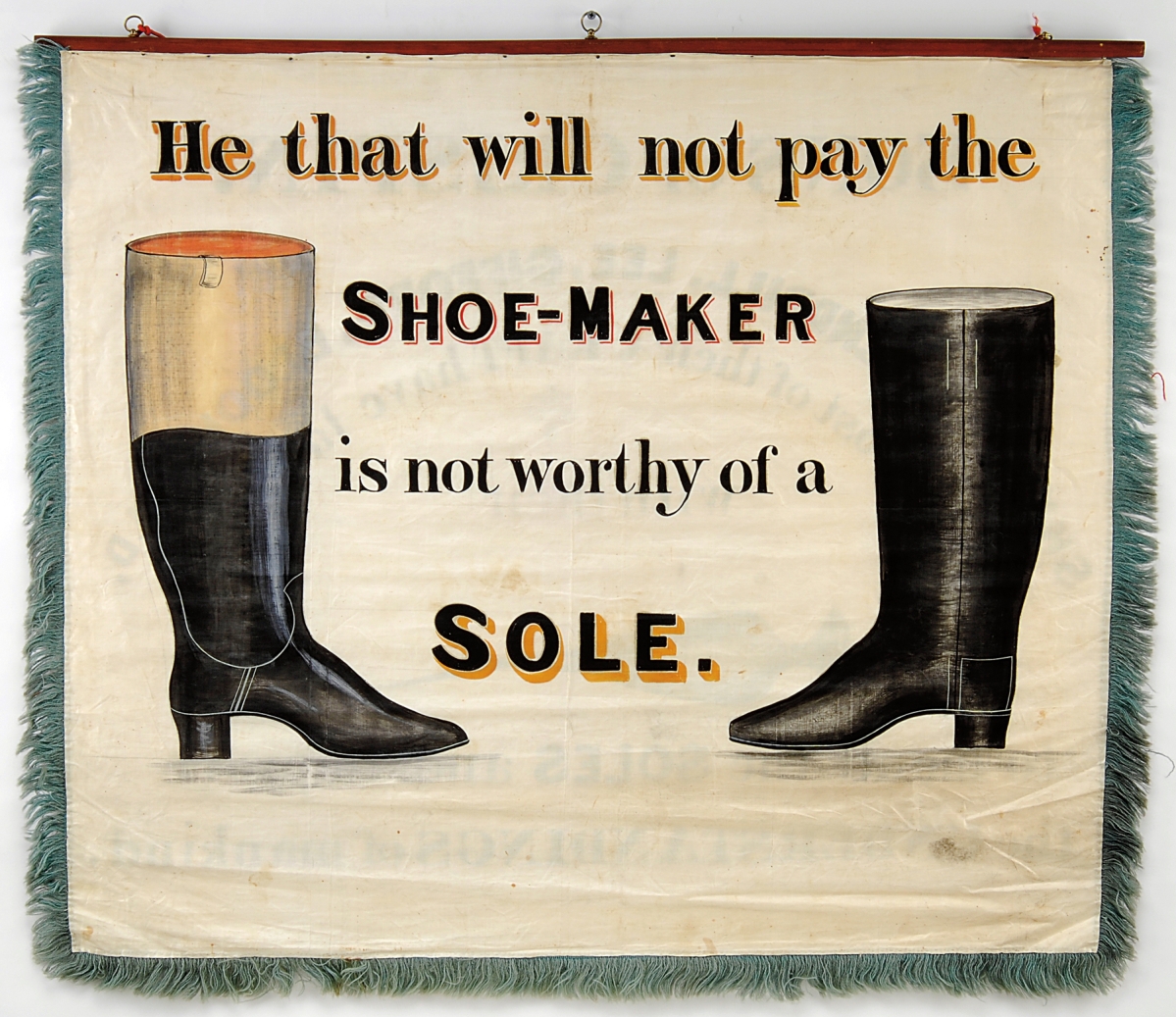

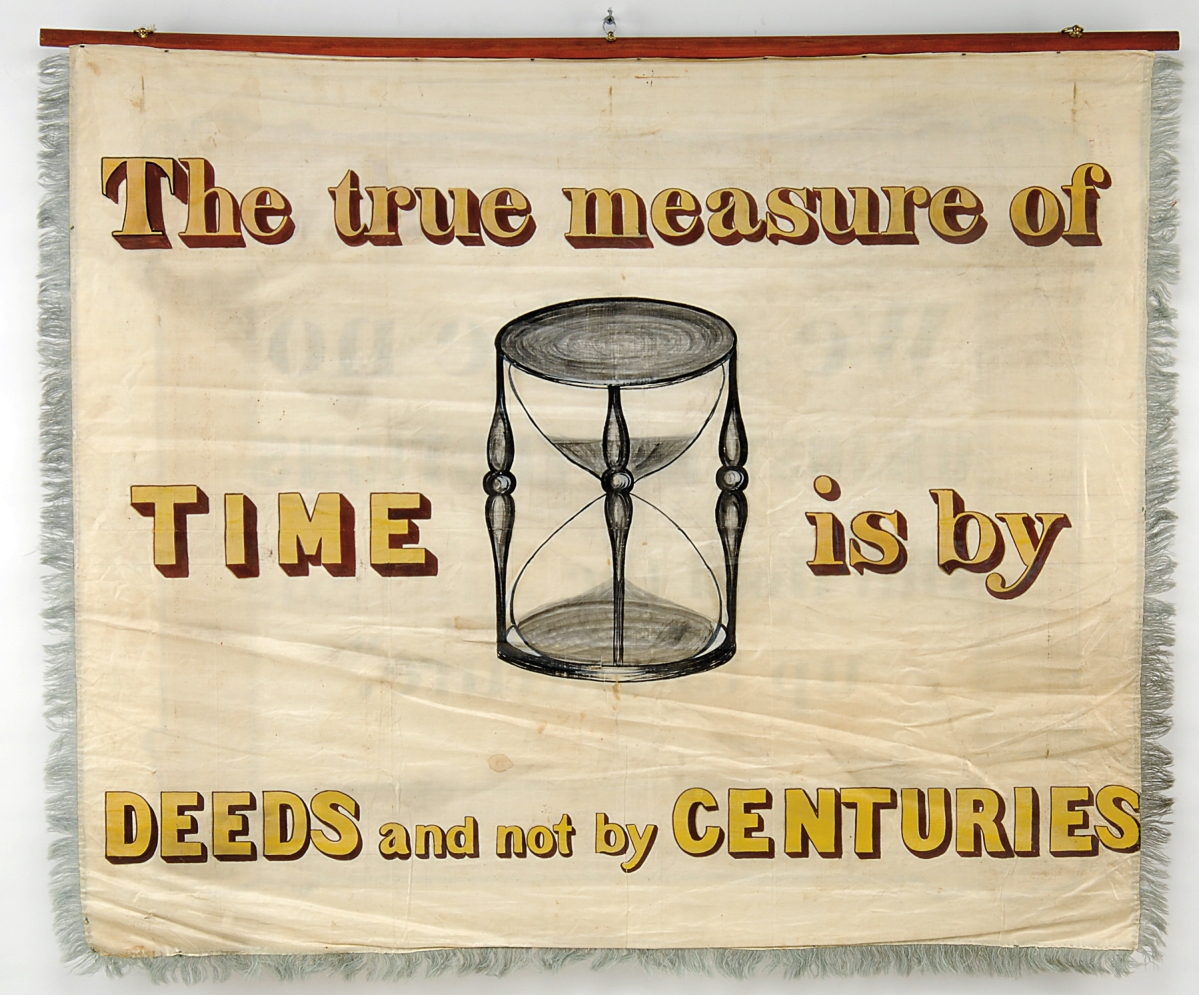

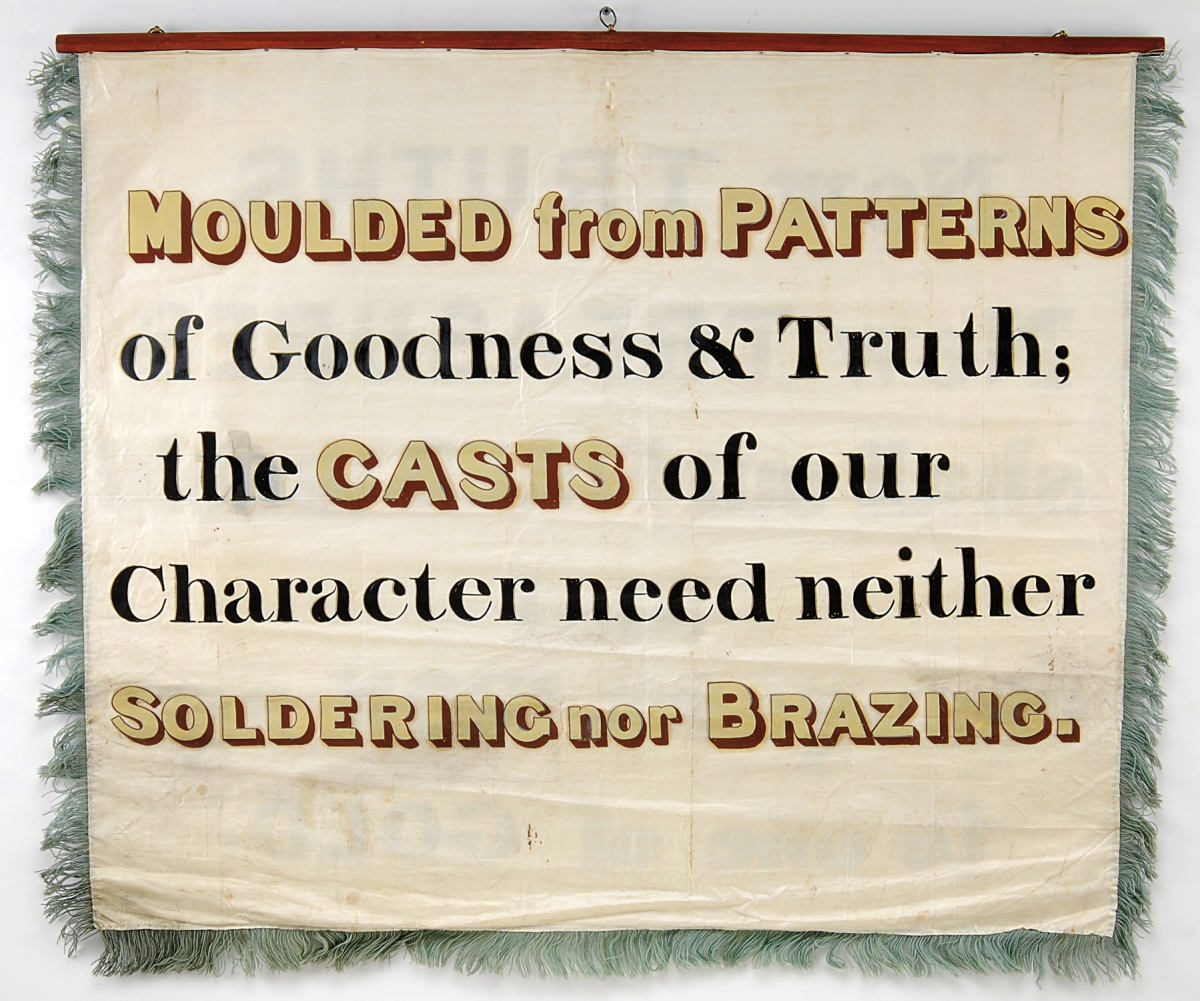

I saw, as Spicer confirmed, that they are not made of silk, as previously reported, but of a heavily varnished fine-grade German linen that has the appearance of oilcloth. The hand painted designs – gilded lettering along with whimsical illustrations of shoes, ships, anvils and the products and tools of other manufacturing trades – float on top of the varnish rather than soak into the fabric, allowing each banner to be lavishly decorated on both sides.

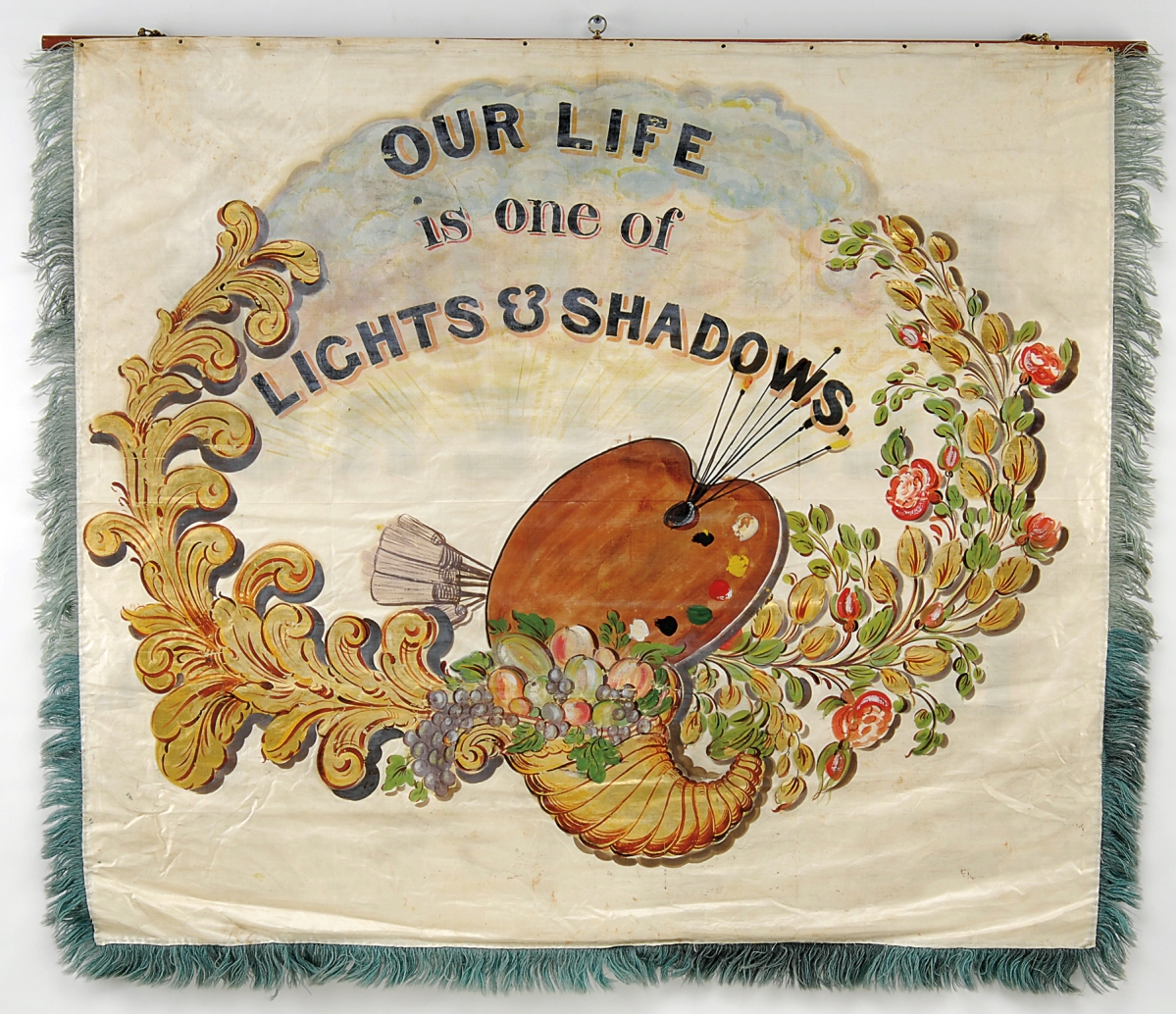

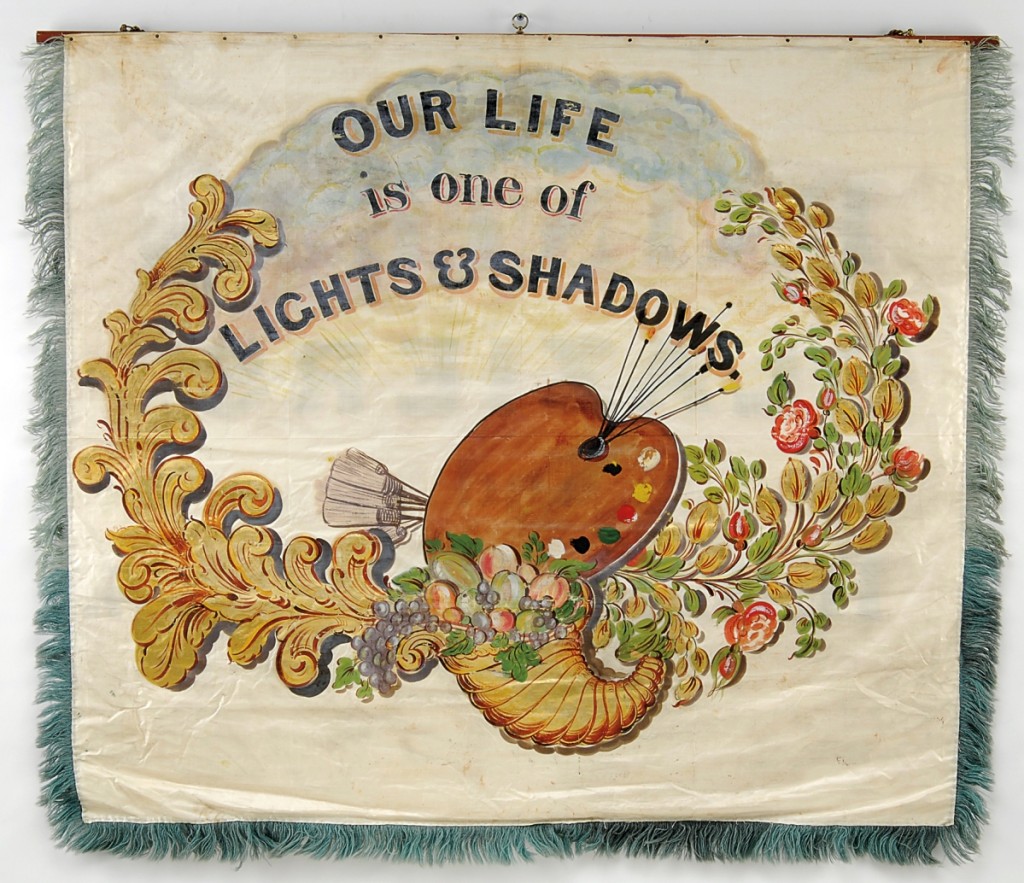

This banner has often been cited as proof positive that the fine arts, and their related industries, were thriving in Portland, Maine, by the 1840s. Painters, Glaziers and Brushmakers banner.All banners are oil on linen and date to 1841. Unless otherwise stated, they are by William Capen Jr. All works are from the collection of the Maine Historical Society, which supplied the photography.

McBrien also demonstrated how the proprietary mounts that Spicer designed allow for two-sided display and also work for storage and travel. Each banner lives inside a kind of sandwich of firm, fabric-wrapped, lightweight board, strapped together with Velcro. With the straps removed, either side of the sandwich can simply be lifted off, exposing whichever side of the banner is desired, and the banner can be exhibited on the remaining sandwich half. There is never a need to remove it completely from its housing. MHS has, of course, also designed custom acrylic-cove red cases for safe display in the exhibition, with the help of Portland-based Prospect Design. McBrien says that while only one side of each banner is visible at a time in the current display, the cleverly designed cases and pressure mounts allow for the possibility of flipping them halfway through the run of the exhibition.

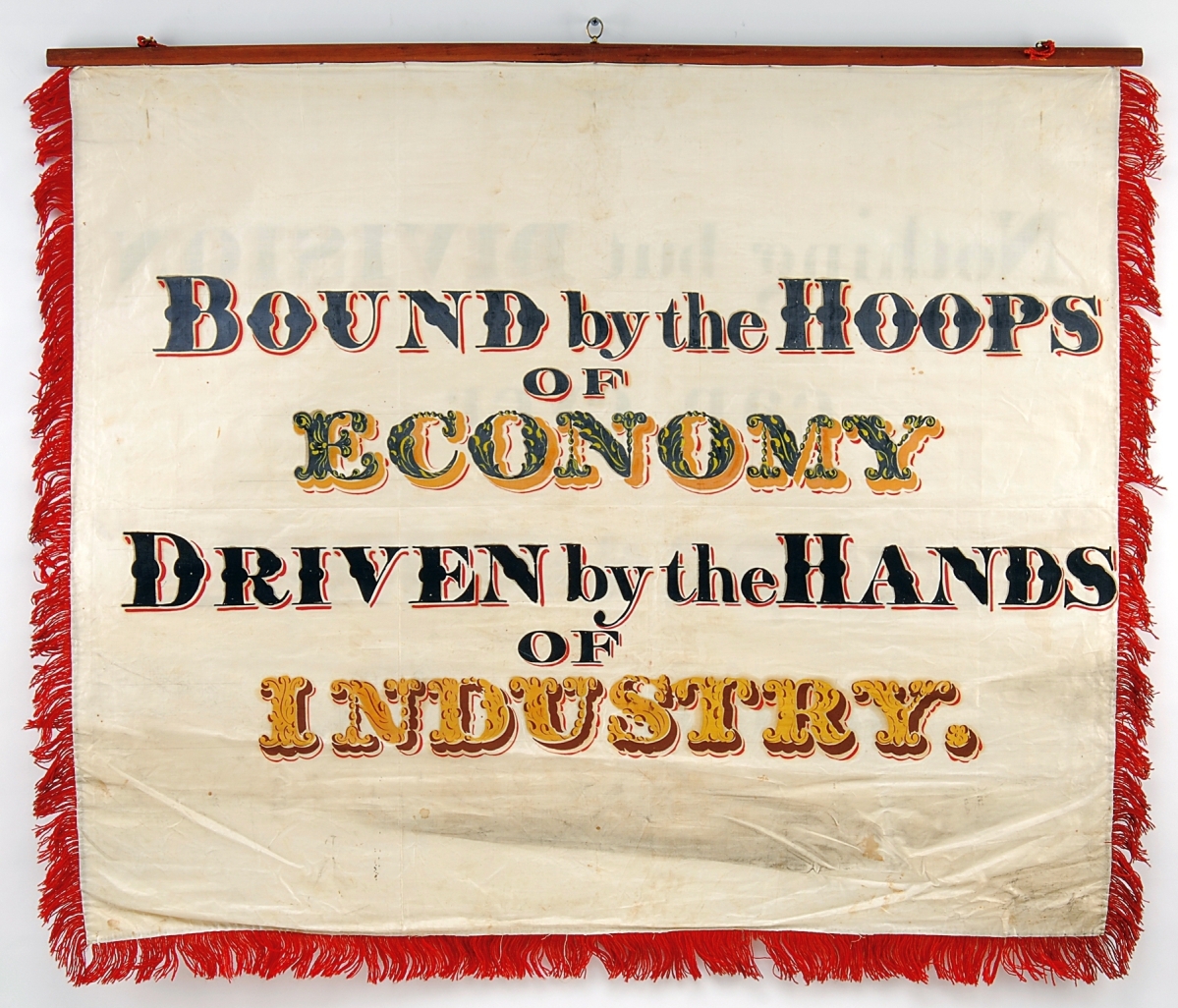

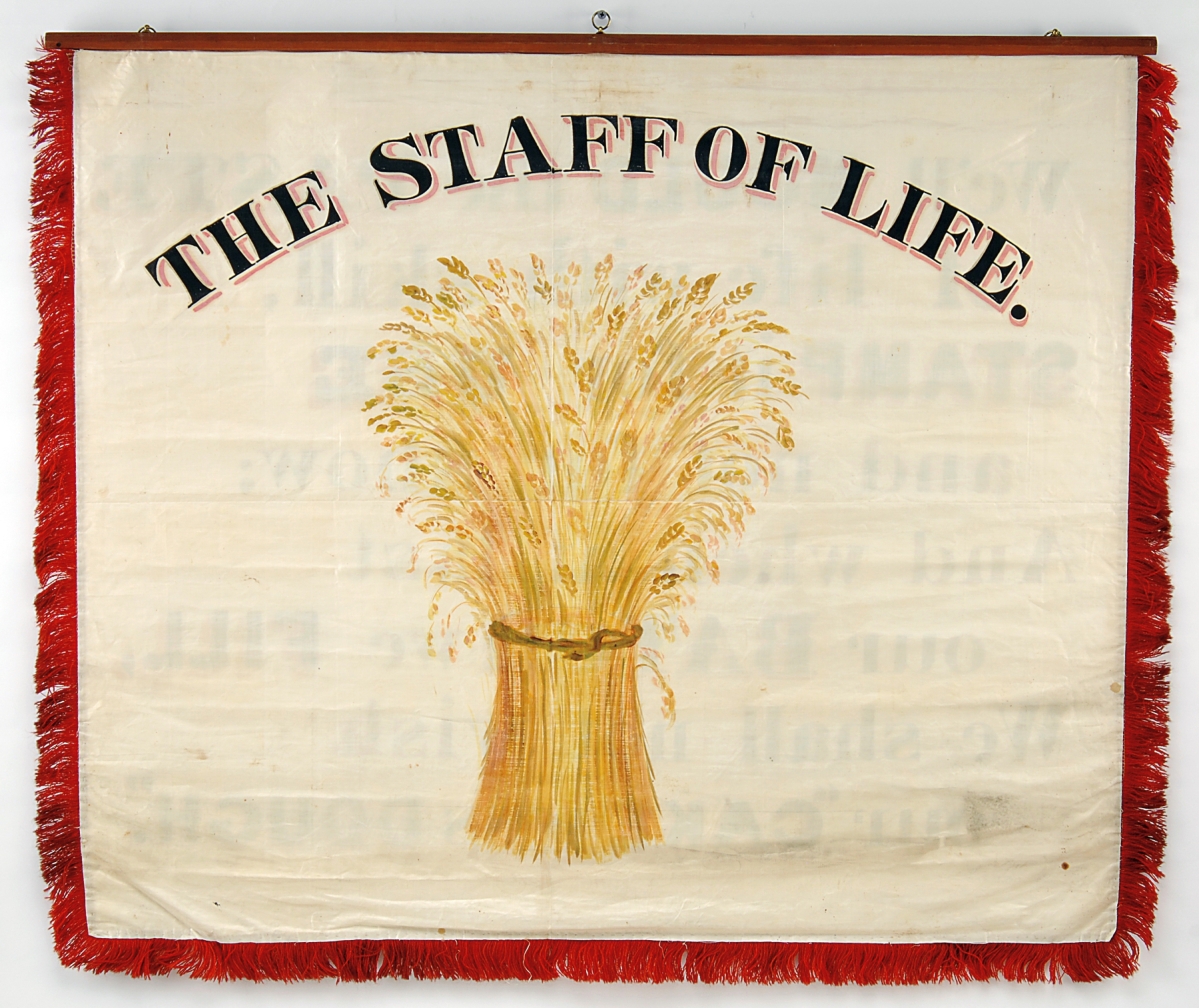

I have taken some trouble to detail the ingenuity behind the scenes of this exhibition because ingenuity and craftsmanship are central themes of the exhibition itself. While today we tend to think of a “mechanic” as someone who fixes broken-down cars or other machines, in Nineteenth Century parlance a mechanic was someone whose livelihood came from his hands, someone who made things in order to earn his living. Many were inventors and entrepreneurs. (The male pronoun is used in recognition of the fact that, while women did play some role in the MCMA, the formal membership was exclusively male until the 1990s.) By 1815, before Maine was even a state, the mechanics of Portland recognized a need to publicly proclaim the value of their vocations and to band together in mutual support. Following the lead of mechanics’ associations in other cities, they incorporated MCMA as a kind of early labor union, dedicated to promoting innovation and advancement in the manufacturing trades and to supporting “unfortunate” mechanics and their families.

“‘Charitable’ is right in the name” of the organization, says John P. Johnson, an independent museum professional and MHS volunteer who has worked closely with McBrien on the exhibition. He observed that in a time of a rapidly changing economy, MCMA allowed its members to have “a common voice – politically, economically, and socially.” He adds, “Today we would call it networking.” Another contemporary word that comes to mind is “advocacy.”

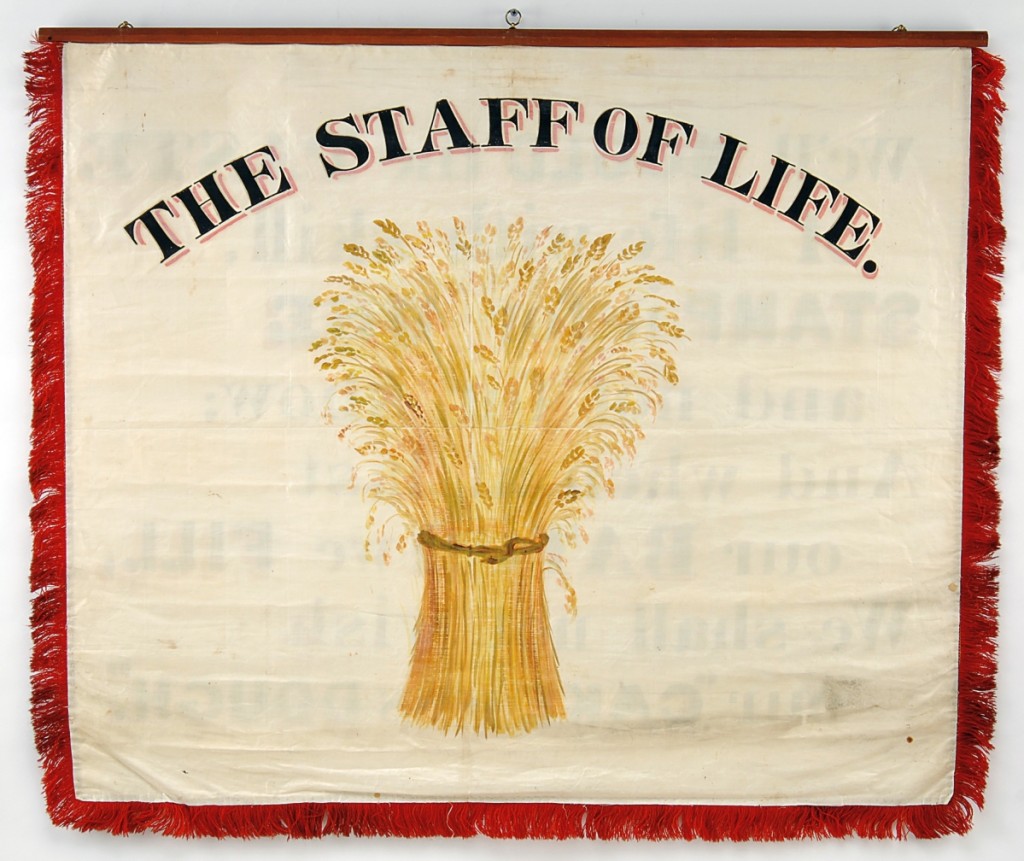

Hence the banners. They were made in 1841 for a parade the Mechanics organized that wound through the streets of Portland, beginning at City Hall and ending at the First Parish Church. A review in the local paper praised the “beautiful” and “tastefully arranged” banners that preceded each group of tradesmen, from butchers and bakers to housewrights and shipbuilders. The reviewer also noted that the printers brought along a working printing press, drawn by two horses, which churned out copies of the parade’s “Order of Exercise.”

The printers’ banner, featuring detailed illustrations of printing presses by printers Arthur Shirley and Samuel Colesworthy, is one of only two in the group not created by the painter William Capen Jr. The other is the boldly painted blacksmith’s banner by Joseph E. Hodgkins. Capen’s “Painters, Glaziers and Brushmakers” banner is one of the standout objects in the show, a luscious example of mid-Nineteenth Century decorative painting. A gilded cornucopia bursts forth into a riot of flowers and scrolls, with a painter’s palette emerging from the center below the words “Our life is one of lights & shadows.”

The reverse reads, “We’ll Mould the Paste of life with skill, Stamp it for Use and not for show; And when at last our Batch we Fill, We shall not wish our ‘Cake was Dough.’” Bakers and Confectioners banner.

Capen surely felt a special connection not only to the painters’ group, but also to the MCMA as a whole. He first joined the organization as a chair maker – probably affiliated with the cabinetmakers – but then changed his profession even as he maintained his membership as a mechanic.

What was the value of being such a faithful member? Beyond the kinds of protections and opportunities that MCMA offered, it also offered a sense of community in very tangible ways. From 1826 on, it presented regular fairs and exhibitions at which members could display their wares, compete for awards and drum up new business. The exhibition at MHS has tantalizing examples of diplomas and medals given out at these fairs. Once MCMA built a permanent home in 1859 – the building it still occupies today – it held classes and lectures and expanded its library. The current MCMA president, Pam Plumb, says that teaching members how to read was a primary purpose of the association in its early days, and that in a time before public libraries, a library of recreational reading was an invaluable benefit to members.

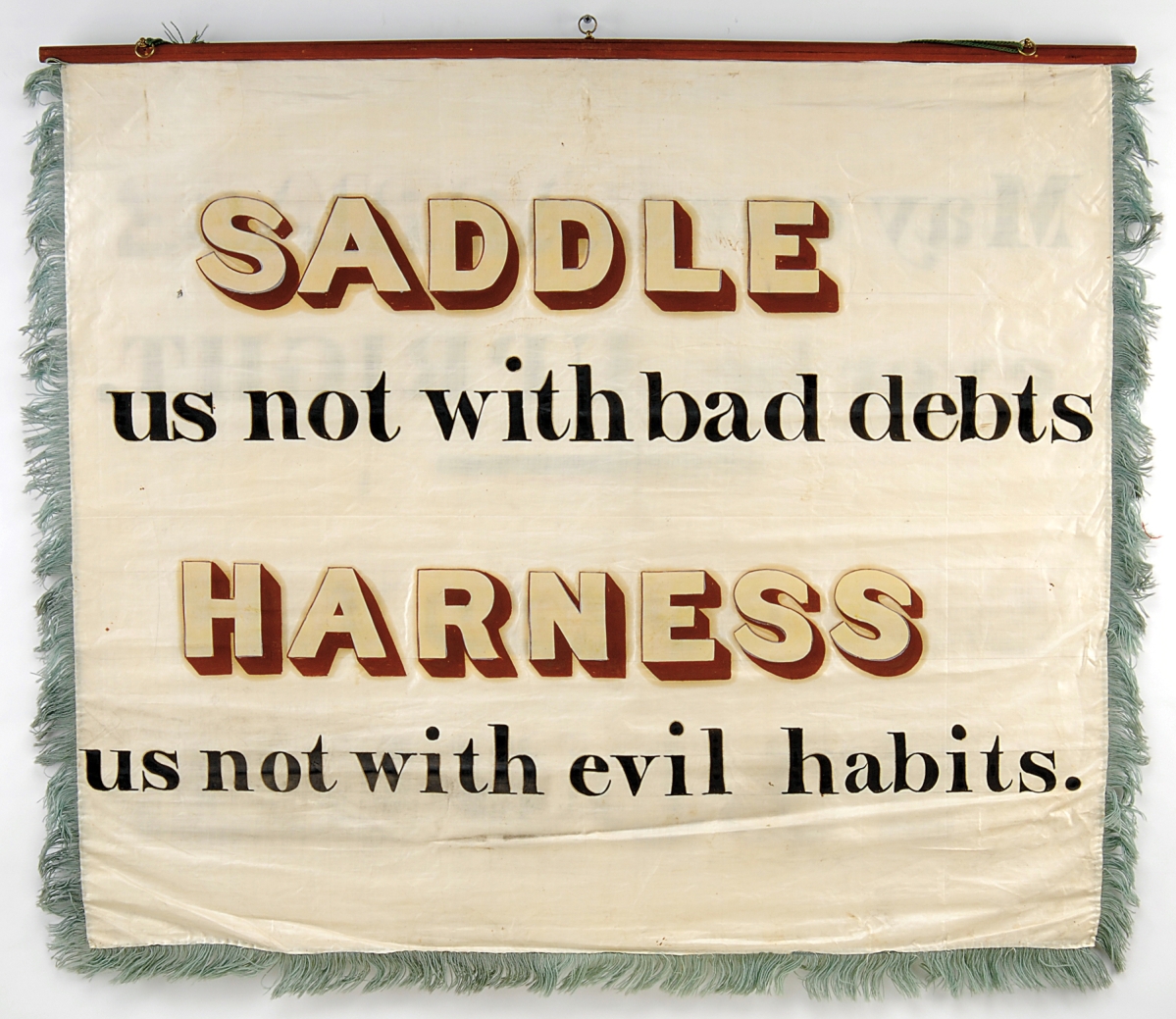

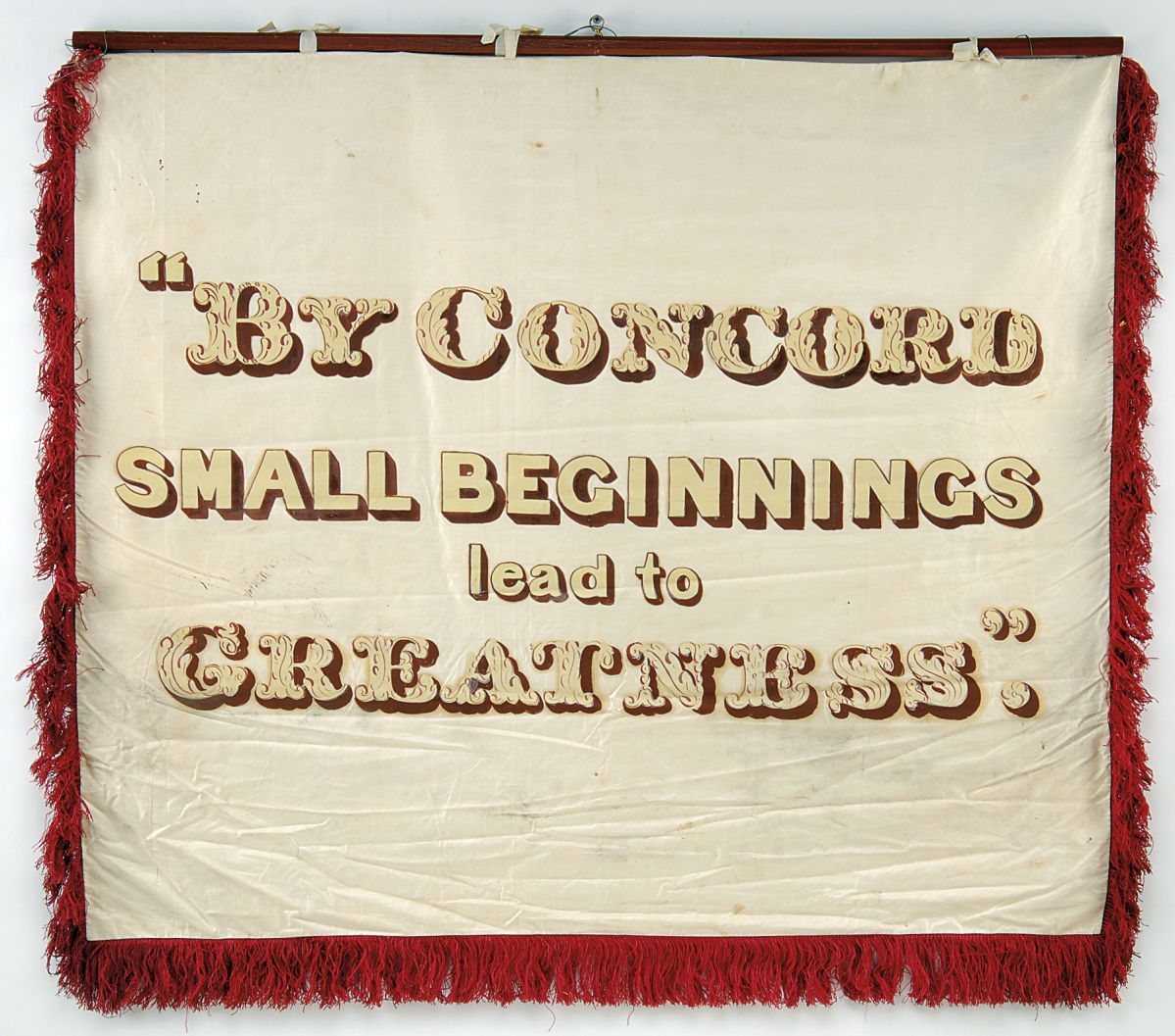

That words and language were a priority for the early MCMA is richly evident in the banners. Many include impeccably lettered witticisms and clever puns based on the specific trade they represent. “United in the bands of temperance,” say the hatters, “we are crowned with honor.” The saddle and harness makers offer equally pithy advice: “Saddle us not with bad debts. Harness us not with evil habits.”

Wordplay was also a feature of the speeches and toasts that were a part of the 1841 parade, and here the shoemakers, whose banner reads “He that will not pay the shoe-maker is not worthy of a sole,” excelled above all. One Henry H. Boody proclaimed to the crowd at the First Parish Church that the shoemaker’s “love is to awl soles, and he sticks like wax to his last.”

The focus of the present exhibition are the 17 historical banners, but MHS has not ignored what the banners represent. Accompanying each one is a collection of artifacts relating to its particular industry, with some conceptual adjustments made for the butchers’ and bakers’ banners, among others. Most of the objects are historical ones from MHS’s collection. In most cases they are connected to a known member of the Mechanics, but some are modern, providing compelling evidence that the manufacturing trades remain a vital part of Maine’s economy.

These are the people, in part, who make up MCMA’s membership today. For the happy epilogue to the banners’ epic story is a renewal and revitalization of the charitable organization that they were designed for. With funds from the banners’ sale supporting urgent building repairs, MCMA has been able to increase its capacity, refresh its programming and grow both its budget and its membership astronomically. Part of this has been about expanding their understanding of “mechanic” beyond narrow definitions of craftsmen or artisans to include workers and innovators in all kinds of fields. As Plumb says, “It’s our hope that we will become again for them what this was for other makers – a sort of convivial place to convene, a place where they could learn useful knowledge, and that might mean in today’s world that they learn how to be small businesspeople.”

Just seven years ago, MHS was dismayed by MCMA’s decision to auction off the banners. Today, the two organizations are actively working together to present and promote the current show, very much to their mutual benefit. “It’s pretty amazing for them to be able to think outside the box and think about how do they continue over the next 200 years,” says McBrien of the reenergized MCMA. “Not every organization can do that.”

“Creative Maine: Trade Banners and the Crafts That Built Maine” is on view at MHS through January 13. The Maine Historical Society is at 489 Congress Street. For more information, www.mainehistory.org or 207-774-1822.

Jessica Skwire Routhier is the managing editor of Panorama, the journal of the Association of Historians of American Art. She lives in South Portland, Maine.