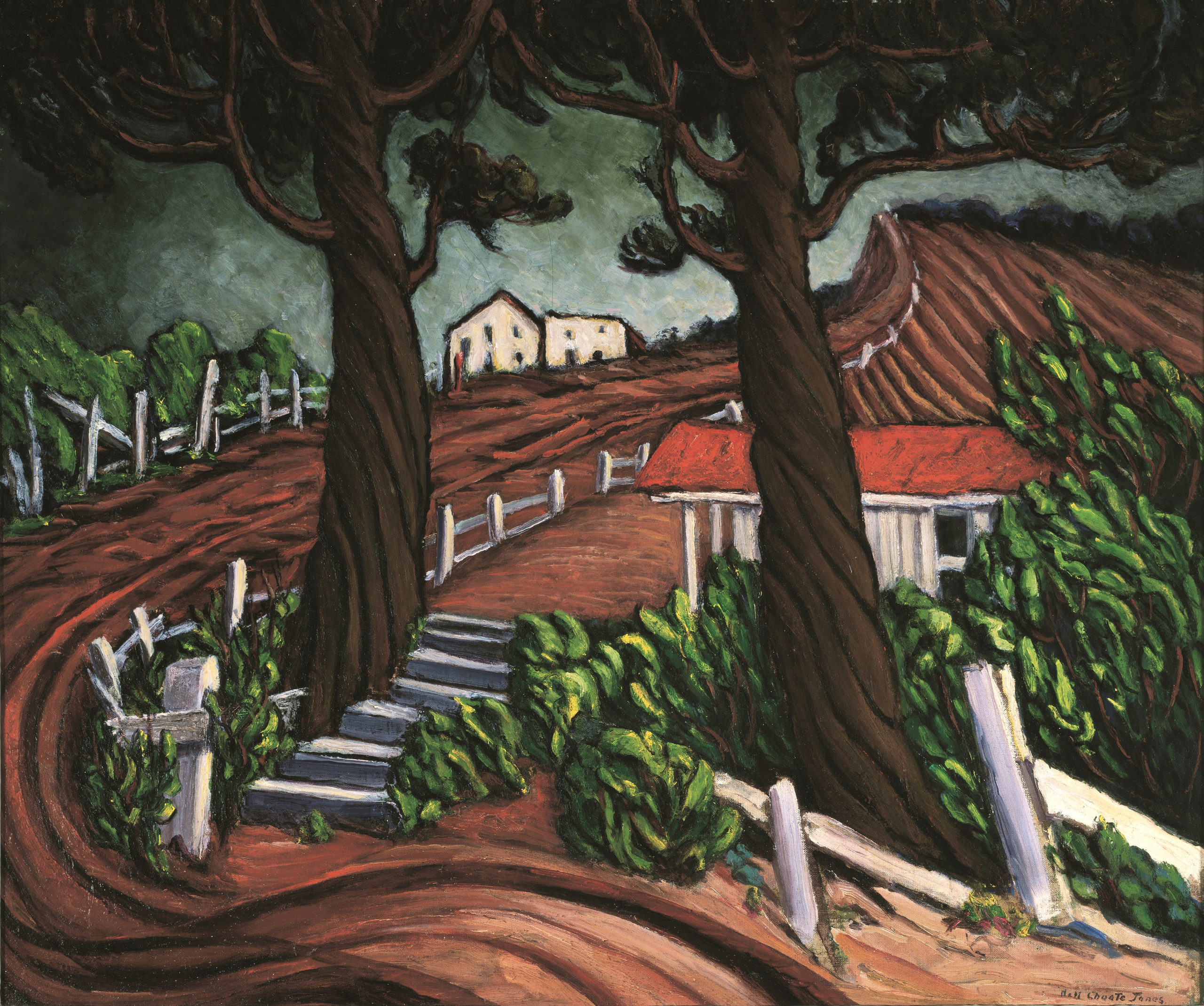

“Georgia Red Clay” by Nell Choate Jones (1879-1981), 1946, oil on canvas. Morris Museum of Art, Augusta, Ga. 1989.01094.

By James D. Balestrieri

ATHENS, GA. — “Southern/Modern,” the new exhibition at the Georgia Museum of Art, organized in collaboration with the Mint Museum of Art, is a discovery of discoveries shared by the curators: Mint senior curator of American art Jonathan Stuhlman, PhD, and independent scholar Martha Severens. With a focus on paintings and works on paper produced between 1913 and 1955 in the states south of the Mason-Dixon Line and east of the Mississippi River, the works on view provide much-needed counterpoint to the prevailing argument that the American South is principally a site of nostalgia for its antebellum past. In truth, and without shying away from the effects of Jim Crow laws and Lost Cause lamentations on art, the exhibition shows artists in the South as far more in tune with Modernist precepts than American art history indicates. Further, the South proved fertile soil for the cross-pollination of Modernism and folk or Outsider art as expressed in strong, simplified forms, quotidian subjects, and a tendency towards the depiction of dreams, spirituality, and what we might call the magically real.

The exhibition embraces expatriates like Romare Bearden and Aaron Douglas, who returned to the region and produced works with an emphasis on southern subjects and goes into some depth about the numerous art colonies that sprang up in the region, notably North Carolina’s Black Mountain College, but also important centers in Louisiana, Alabama and elsewhere. I will discuss the expatriates, the famous artists who visited and painted in the South, and the schools that incubated the Southern/Modern movement. But it is, perhaps, the painters who are less well-known outside of the South who provide the most breathtaking moments in the exhibition.

The oils and pastels of Will Henry Stevens (1881-1949), who was born in Indiana but resided in Louisville before becoming a professor of art in New Orleans in 1921, are, for example, a revelation. I cannot think of another American painter who took Kandinsky to heart — and the exhibition’s catalog attests to the influence — and transformed his ideas into a distinctly American facture. “Paintings such as ‘Untitled’ (1944, fig.9), a pastel on paper, adapt Kandinsky’s proto-abstract expressionism for a local environment, incorporating images of gently torqued leaves in the storms of color. [Josef] Albers praised Stevens’ musicality and affirmed their comradeship” (cat. p. 217).

Untitled by Will Henry Stevens (1881-1949), 1944, pastel on paper. The Mint Museum, Charlotte, N.C. Gift of the Janet Stevens McDowell Trust. 2006.12.5.

By investing abstraction with natural forms, Stevens seems to be embodying the opening lines of William Blake’s poem, “Auguries of Innocence:” “To see a World in a Grain of Sand And a Heaven in a Wild Flower…” Consider the green leaf at upper left. On one level, it is a leaf — floating, perhaps, casting its shadow onto the bed of a puddle or pool. Spots of red suggest the rust of decay. And yet, from another angle, one can imagine the leaf as a landscape unto itself, in miniature. The pale yellow spine might be a road or path, the red spots, some sort of indigenous bushes dotting a field. In this scheme, the area above the path or road becomes a thick woods and the edge of the leaf is a distant tree line. Extend this vision and the entire painting acquires a topography, viewed from on high. Droplets of water become lakes, edges of bark become mountain peaks, curves become edges of worlds. But even this paradigm is subverted by the red leaf that seems to sail from left to right through the picture plane, shifting our eye back from macro to micro. It is the sort of picture that rewards the viewer time and again.

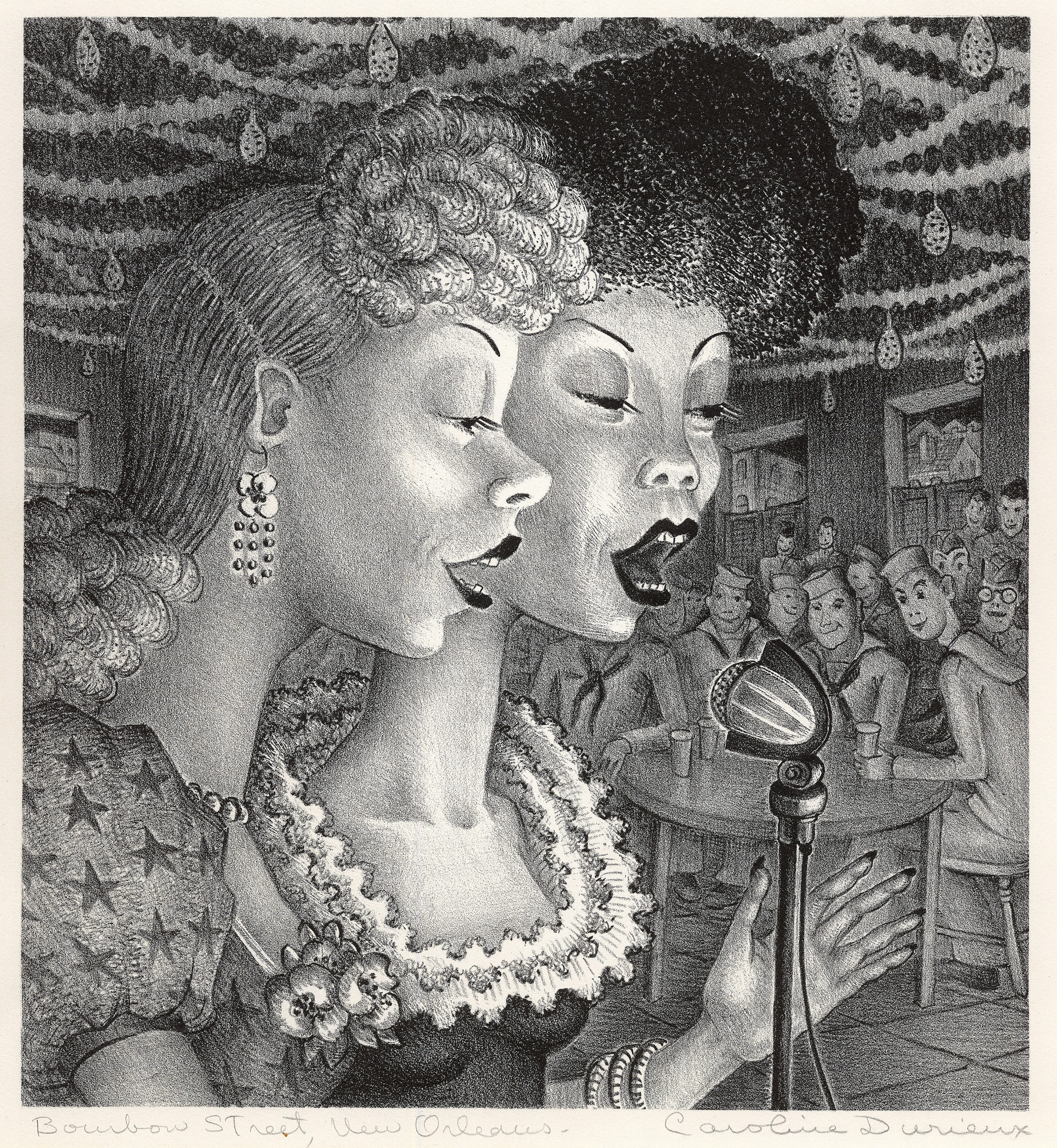

We associate music with the American South, and, indeed, one entire catalog essay is devoted to the influence and representation of music on Southern art. Printmaker Caroline Durieux (1896-1989) was an alumna of the university art program at Sophie Newcomb College in New Orleans and went on to run the Federal Art program in Louisiana before becoming a professor at Newcomb, and, later, at Louisiana State University. Durieux was a restless experimenter, even patenting a process for incorporating radioactive materials into printmaking, but the majority of her work has a satirical bent. “Bourbon Street, New Orleans,” a 1934 lithograph, appears, on its surface, to be an example of social realism characteristic of the period. A pair of Black singers dominate the picture plane, singing — open-mouthed — into a microphone, while the audience — white male sailors — listen with attentive appreciation. But the viewer can feel a social chasm between the women and men. The open mouths of the singers, especially the one on the right, seem to be about to devour the sailors — who look as if they wouldn’t mind being devoured. But whatever sexual tension obtains in the piece, the exaggerated foreground-background relationship creates a visual chasm — a pictorial illusion, really — suggestive of an unbridgeable racial distance.

“Bourbon Street, New Orleans” by Caroline Durieux (1896-1989), 1934, black lithograph on paper. LSU Museum of Art, Baton Rouge, La. Gift of the artist. 63.9.18.

Romare Bearden’s (1911-1988) “Cotton Workers,” Aaron Douglas’s (1898-1979) “The Toiler,” Elizabeth Catlett’s (1915-2012) “War Worker” and Thomas Hart Benton’s (1889-1975) “Ploughing It Under” all indicate the national influence of the WPA style that characterized American art during the Depression and through World War II. Each work, however, underscores the Black experience of the era, conveying the sense of greater hardship added to already marginal lives of poverty. Each of these works, in the individual, personal styles of the artists express a combination of world-weariness, a sense of doing what must be done, along with resilience, and, at least in Bearden’s painting, a feeling of community — that whatever comes, we will face it together. And while none of this social realism is strictly Southern, the spirituality of “The Toiler” — who may be cursing heaven, or singing — the blue sky in “Ploughing It Under,” and the strength of character in the portrait of the “War Worker,” allow us to find empathy and make common cause with the subjects of the works. There is a religious sensibility underpinning — a feeling of faith — in these and many of the paintings, drawings and prints in the exhibition that is far more Southern than the big-shouldered WPA paintings of the Midwest we are accustomed to seeing.

Elaine de Kooning’s (1918-1989) “Black Mountain #6,” painted in 1948 during her time in residency at Black Mountain with her husband Willem, is an excellent example of the kind of work that stimulated the artists in “Southern/Modern.” The latticework window and aperture forms, heavily outlined in black, recede and come forward in opposition to the more sinuous white paths and shapes, imparting a dimensionality that defies the apparent overall flatness that is expected in Abstract Expressionism. It is almost as if the concrete reality of place — the South — intrudes on artistic practice. What do these “windows” look into, or out onto? To what destinations and culs-de-sac do these white paths lead?

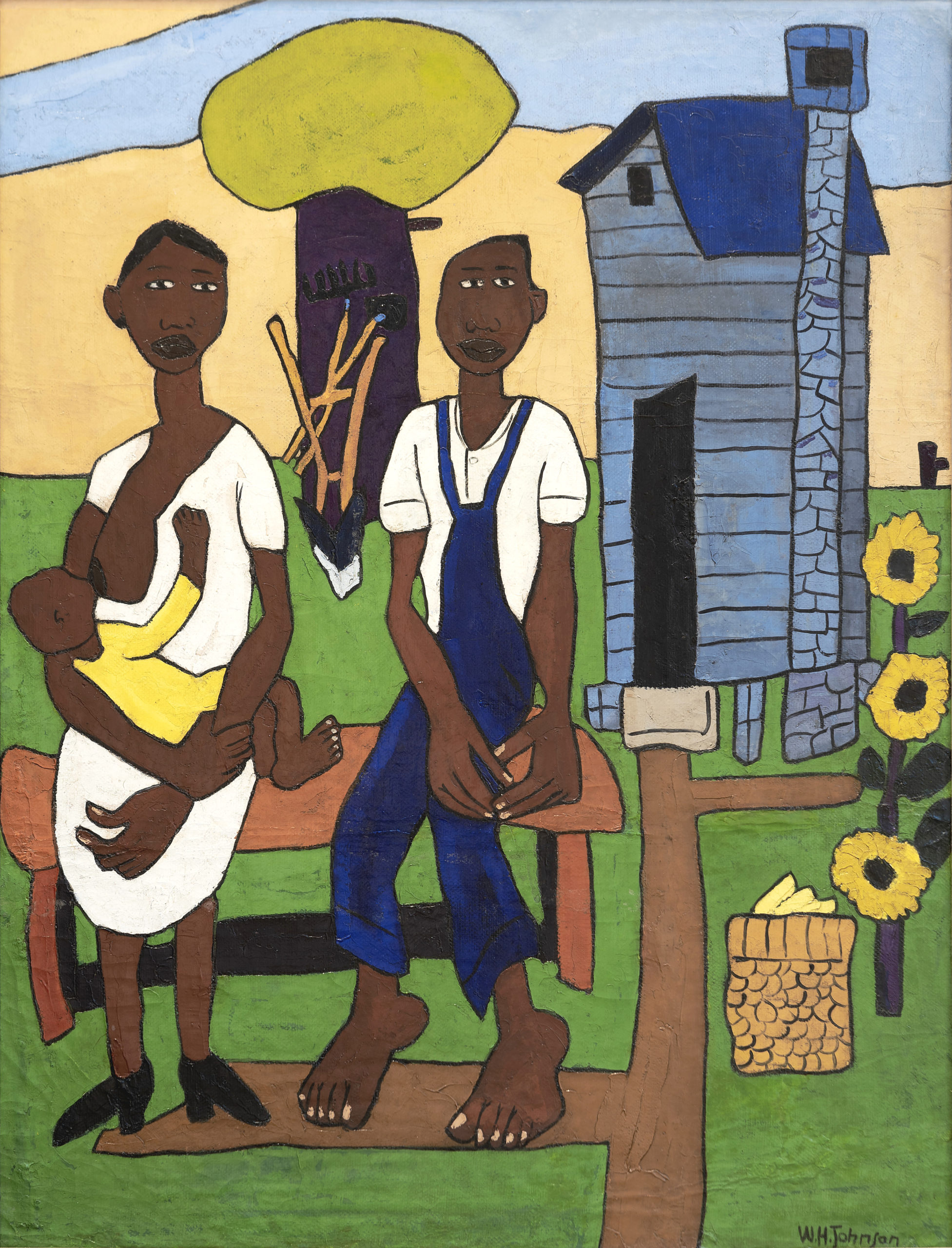

“Evening” by William H. Johnson (1901-70), 1940-41, oil on burlap. Florence County Museum, Florence, SC. Gift of the National Collection of Fine Arts, Smithsonian Institution. 1344.2.

Questions of race, spirituality and the intrusions of urban, industrial life on the historically agricultural South permeate the artworks in “Southern/Modern.” The uniqueness of the various landscapes, from estuaries and bayous to fertile fields and forested mountains, shimmer in the background of the exhibition. But the artists resist their pull, even when they paint Southern subjects and incorporate Southern forms and themes. Mississippi artist Dusti Bongé (1903-1993) evolved a style that was part Cubism, part Surrealism and part Social Realism. Her 1940 painting, “Where the Shrimp Pickers Live,” might serve as precursor to de Kooning’s “Black Mountain #6” in the alternation between the outlined doors and windows and the mostly white laundry blowing in the wind. If we didn’t have a title, we wouldn’t know that this is “where the shrimp pickers live,” but their exact occupation matters little. We surmise that they are working people, living together in some mutuality, bound — tied might be a better word, considering the clotheslines strung between the modest dwellings — by occupation and social status. Still, imagine how, through a process of reduction and abstraction, Bongé’s “realistic” scene might be transformed — essentialized and economized — into de Kooning’s abstraction.

“Reversible Image,” a late oil by Charles H. Walther (1879-1937) — who would find recognition at the Museum of Modern Art after being fired from his post as a teacher at the Maryland Institute College of Art for his devotion to an exploration of Modernist principles — shows the artist’s complete investment in abstraction, even referencing Dadaism in the suggestion that the painting can be hung in any number of ways.

If there is a single painting that captures “Southern/Modern,” it might be “Story Told By My Mother,” by Arkansas-born Carroll Cloar (1913-1993), who achieved some fame in New York City before falling “into artistic obscurity” after his relocation to Memphis. Storytelling sits at the heart of the American South, whether one is speaking of William Faulkner or the Mississippi Delta Blues. Cloar’s narrative take on the Surrealist tradition forms a strong through line in his work. In “Story Told By My Mother,” we seem to see the “story” of his mother meeting a black panther in what seems to be early spring, when the plants are just beginning to pop through the mantle of snow, as if in a dream, or through the eyes of a rapt son, a child spinning the tale of the encounter into a fable. Cloar turns this filtering of experience through language, this tale-spinning, on its head. This is a painting about listening — part folk art, part Surreal sophistication. It’s about how our imaginations take the stories we hear and give them life in our minds in imagery. The mother’s silver hair echoes the snow; her black dress links her to the panther and the trunks of the trees. Her foot and hand suggest that she is running away but she looks back at the panther, who regards her with a combination of alertness and indifference. The sky is yellow-orange, dawn or dusk perhaps, light fading to shadow.

“A Story Told by My Mother” by Carroll Cloar (1913-93), 1955, casein tempera on Masonite. Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, Memphis, Tenn. Bequest of Mrs C.M. Gooch. 80.3.16 © Estate of Carroll Cloar.

This is perhaps what unites the outstanding works in “Southern/Modern” — the feeling that they are as dedicated to the portrayal of artistic reception — seeing and listening — as opposed to production. Instead of saying, “This is how I see the world,” these works depict the question, “How do I see the world?” It’s a hard thing to make clear, this difference, but let me leave you with this. Take the subject of Cloar’s “Story Told By My Mother,” then imagine it in Salvador Dalí’s hands. It would be a masterpiece, replete with symbols and statements, fragments of dreams and nightmares, offering a bravura aesthetic politics all its own. Now turn back to Cloar’s painting and you may see what I am driving at — that it’s a work that asks a question, that beckons you to listen, not a statement that answers one. See “Southern/Modern” — and ask your own questions.

“Southern/Modern” is at Georgia Museum of Art through December 10, after which it will travel to the Mint Museum Uptown in Charlotte, N.C., where it will be on view to October 1, 2024.

Georgia Museum of Art on the campus of the University of Georgia is at 90 Carlton Street. For information, 706-542-4662 or www.georgiamuseum.org. The Mint Museum is at 500 South Tryon Street. For information, www.mintmuseum.org or 704-337-2000.