By Jessica Skwire Routhier

LEWISTON, MAINE – Just a year ago, Sara Torres had never heard of Dahlov Ipcar. An education researcher at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, Torres was deep in the archives, researching MoMA’s revolutionary first director of education, Victor D’Amico. Among D’Amico’s myriad achievements, he is noted as the curator for the museum’s first solo exhibition of a woman artist in 1939. The exhibition was “Creative Growth, Childhood to Maturity,” and the artist was Dahlov Ipcar, just 21.

Although Ipcar’s name is indeed well-known among those who study children’s literature – she was the author and illustrator of dozens of bestselling titles from the 1940s through the 1970s – and although she is a bona fide celebrity in Maine, which had already become her permanent home by the time of the MoMA exhibition, it is not particularly surprising that her name was unknown to Torres. While Ipcar was a visionary, iconoclastic, ambitious and widely exhibited painter throughout her long life – she died, at 99, in February 2017 – early on she consciously separated herself from the postwar New York art world, which was dominated by abstraction. As a result, she was largely ignored by the most influential critics of the time, who determined the canon of American art history for at least two generations. Even MoMA, which showed such prescience in organizing the 1939 exhibition, ultimately embraced the prevailing view of Modernism as roughly synonymous with abstraction, leaving Ipcar and others who used figural motifs and worked from their imaginations outside the circle of recognition.

Torres, intrigued by the “Creative Growth” exhibition and its unfamiliar headliner, did as many modern scholars do: she consulted Google. The results led Torres to Maine’s Ogunquit Museum of American Art (OMAA), which was planning a partial recreation of the “Creative Growth” exhibition – set to open, unbelievably, the very next day. Ipcar had, it seems, kept most of the original material from that 1939 show, and as her 100th birthday in November 2017 approached, she eagerly anticipated revisiting the exhibition as a cornerstone of her long life in the arts. Sadly, she died less than three months before the OMAA exhibition opened. The museum, however, worked closely with her family to present the exhibition much as she envisioned it, albeit now as a memorial celebration instead of a birthday one.

Ipcar’s family is, of course, a crucial part of her story. She was the younger child and only daughter of Marguerite (1887-1968) and William Zorach (1887-1966), both acclaimed artists of the early Twentieth Century. Their names are certainly known to all at MoMA. Much has been written, some of it by Ipcar herself, about how the family integrated their art and their domestic life, creating nurturing and visually engaging environments, in New York and Maine, in which to live and work. The point of the 1939 MoMA show, and its re-creation in Ogunquit, was to demonstrate how the Zorachs’ unique approach to life, art and education was the bedrock for their daughter’s own artistic sensibilities. It was less about how they shaped her artistic education and more about how they provided a space in which her creative self – and that of her brother, Tessim – could flourish independently.

“They were, at the time, unlearning what they had learned in a traditional art education,” says Torres of Marguerite and William, “so they decided that in order for their children to be creative, another pedagogy was needed…It was not so much about making her [Ipcar] an artist; it was about making her a very creative human being and being fully awake in the world.”

In communicating with Ipcar’s family, who are enthusiastic keepers of her legacy, Torres connected with Rachel Walls, who represents Ipcar’s estate in Maine. Walls then let Torres know of the Bates College Museum of Art’s (BCMA) plans for a 2018 exhibition and connected her with its organizer, Anthony Shostak, BCMA’s education curator. Shostak notes that the original plan for Bates, as for Ogunquit, was to use the occasion of the exhibition to celebrate the centennial of Ipcar’s birthday. Ipcar’s death and a shifting timeline made that an impossibility, but the exhibition still coincides with the anniversary. In that sense, Shostak says, “we’ll still be celebrating with her.”

Learning of Torres’s interest in Ipcar and research into the artist’s history with MoMA, Shostak invited Torres to contribute an essay to the catalog. The re-creation at Ogunquit had not included a catalog, so this would, in effect, complete the project that the museum had boldly begun. Appropriately, the works on view at Bates would be not the youthful creations exhibited at MoMA and Ogunquit, but mature works that showed the full flowering of Ipcar’s creative spirit, nurtured and supported by a learning environment that had allowed her every opportunity to pursue what inspired her.

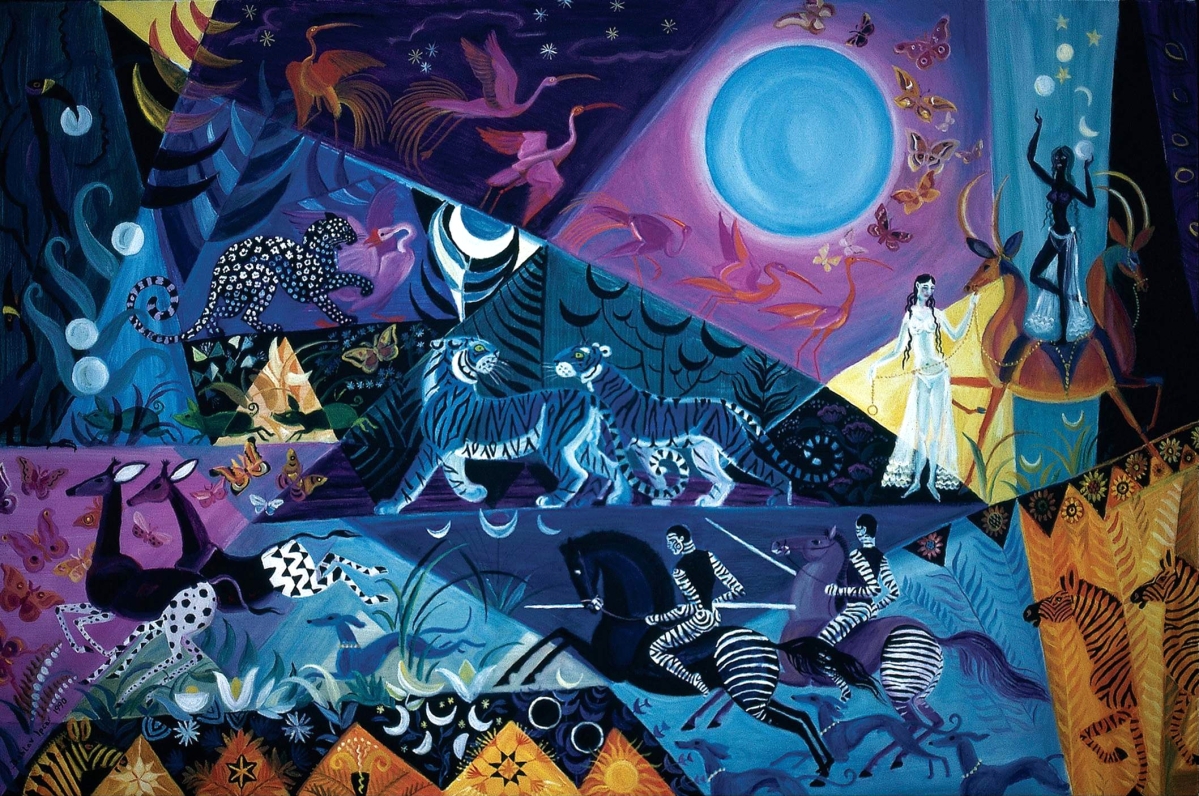

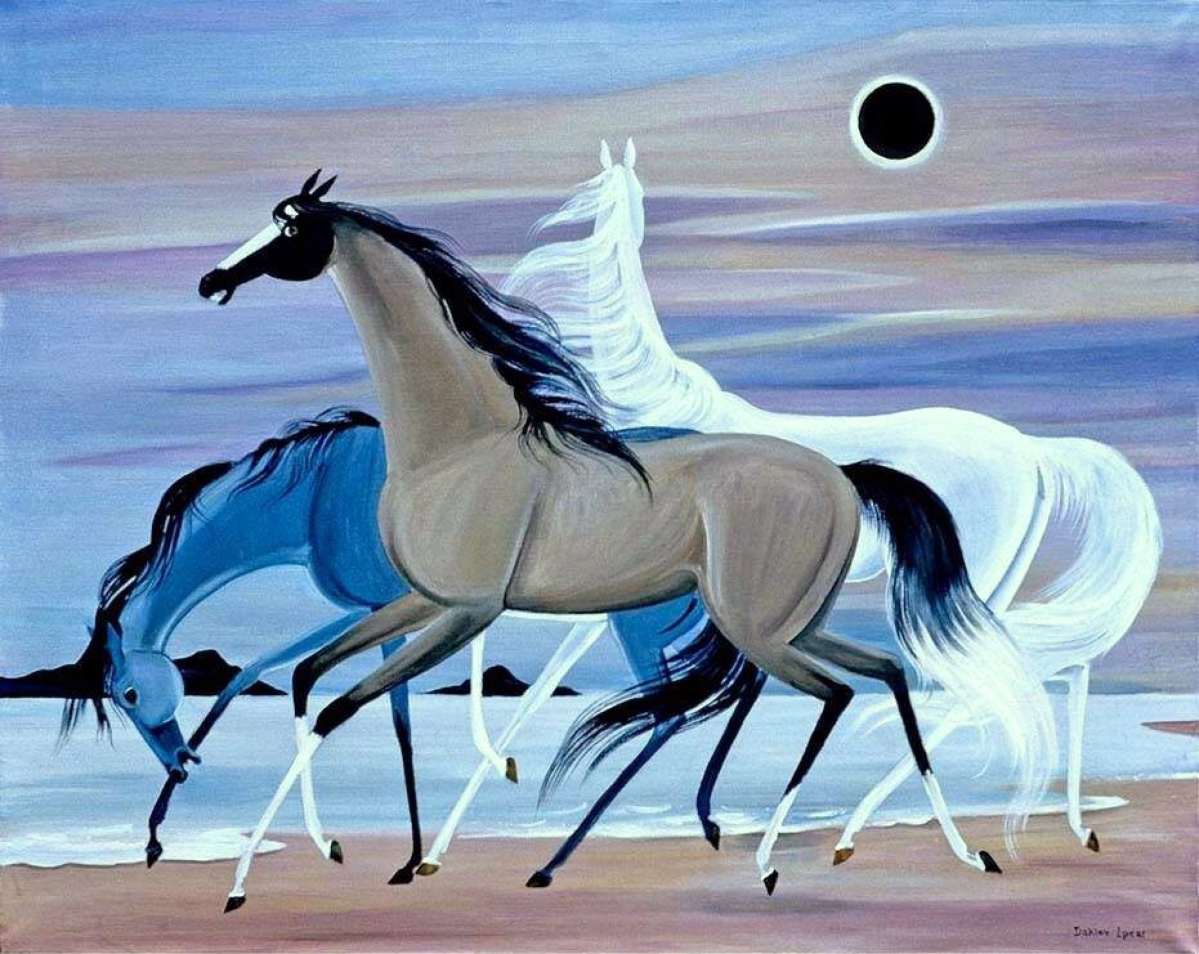

The works on view in “Blue Moons and Menageries” support this concept in a direct and specific way. Shostak said he and Walls had been looking for a way to take a fresh look at Ipcar’s work, which is exhibited frequently in Maine. “Right at the start,” Shostak says, “we were thinking that it would be fun to try to exhibit some of the works that Dahlov didn’t show that much.” (Both Shostak and Torres, like other scholars of Ipcar’s work, many of whom knew her personally, refer to the artist by her given name.) The Blue Moon paintings, he says, “are a bit of a departure” from her more popular works, which are colorful and kaleidoscopic images of animals, domestic and exotic, in semi-Cubist landscapes. These, by contrast, are “a little dreamier, a little stranger…sort of dark,” he observes, noting the presence of mythological creatures and celestial phenomena like comets and eclipses. More, perhaps, than the works that have made Ipcar one of Maine’s best-loved artists, these paintings show that she gave her imagination free rein.

The works on view in “Blue Moons and Menageries” support this concept in a direct and specific way. Shostak said he and Walls had been looking for a way to take a fresh look at Ipcar’s work, which is exhibited frequently in Maine. “Right at the start,” Shostak says, “we were thinking that it would be fun to try to exhibit some of the works that Dahlov didn’t show that much.” (Both Shostak and Torres, like other scholars of Ipcar’s work, many of whom knew her personally, refer to the artist by her given name.) The Blue Moon paintings, he says, “are a bit of a departure” from her more popular works, which are colorful and kaleidoscopic images of animals, domestic and exotic, in semi-Cubist landscapes. These, by contrast, are “a little dreamier, a little stranger…sort of dark,” he observes, noting the presence of mythological creatures and celestial phenomena like comets and eclipses. More, perhaps, than the works that have made Ipcar one of Maine’s best-loved artists, these paintings show that she gave her imagination free rein.

The BCMA, for example, owns “Revelation of the Lamb” (1972), inspired by the biblical Book of Revelation and featuring a seven-eyed, seven-horned ram. “It’s so bizarre compared with her barnyard scenes,” says Shostak. Presenting it alongside other provocative works from her self-titled “Blue Moon” series, most of which remain in the possession of Ipcar’s family members and are made available through Wall, will give this enigmatic painting some context. Together, the works on view will also shed light on a…theme? concept? vision?…on something, at any rate, that occupied Ipcar’s imagination and inspired her art over a period of nearly 50 years, from 1965 (“Dark of the Sun”) to 2014 (“Blue Moon Dance”).

Because these were, to some extent, created as private works – Shostak notes that some were given directly to family members and have remained in their hands – many of them have “either not been seen or have been seen so seldom that an entire generation has not seen these works.” Foregrounding them in this exhibition makes a compelling case that “she’s a more complex painter with broader visions than someone might have expected.”

That said, the exhibition does not ignore her exemplary career as an illustrator whose works have engaged children for generations, and that capture a child-like spirit of wonder and fascination with the world. The BCMA includes several of her “soft sculptures,” for instance – some made as toys for her children and grandchildren – recognizing them as part and parcel of her lifelong creative experiment. Shostak identifies among favorite objects in the show a graphite drawing of “Otto,” the family’s pet salamander, and a watercolor inspired by it that later appeared as an illustration in her book Animal Hide and Seek (1947). Shostak says that these works provide evidence that Ipcar approached “drawing as a way to understand something.” The practice, it might be observed, is just as applicable to understanding eternity as it is to understanding a salamander.

Because both Shostak and Torres are educators, I asked them both what we might take away from Ipcar’s formative artistic experiences. What lessons are there for today’s students and teachers of art? “She was taught by example,” Shostak observes, so “she could work over [her parents’] shoulders and see how they worked in a whole variety of media.” Painting, printmaking, textiles and sculpture were all in the Zorachs’ oeuvre. “These days there are fewer and fewer parents who do this as a hobby.” The challenge, he argues, is “how to provide students, young people, the access to very accomplished and confident practitioners that they can just sort of watch. I’m also pretty sure that Dahlov had access to really good materials,” he adds. “The kind of materials you give a student to work with may have an impact in how much they enjoy working with their medium.”

But above all else, Shostak says, “The Zorachs apparently did not really judge Dahlov’s work. They were very supportive of it, and I’m sure they offered her guidance when she asked for it, but they really let her explore her own interests.” Torres agrees, adding that Ipcar’s story argues that “we need to reconsider children as unique creative individuals; not as artists or as ‘gifted’ or talented, just as human beings with that creative potential… It’s not about painting or drawing; it’s about being fully awake in the world.” She points out that Ipcar was chosen for the 1939 MoMA show not so much because she was exceptional or a prodigy, but because D’Amico saw her as an example of how a normal, healthy child whose imagination is stimulated and encouraged can develop creatively. “[Marguerite and William] would say they did nothing, but they did a lot in doing nothing; what they considered ‘nothing’ was giving [their children] the chance to evolve their own way, and that’s a lot.” Torres expresses regret that art-making is now thought of, in most schools, as an “extracurricular thing…just for free time” when in fact “art is intrinsic to life” and “we are embedded in art.”

This is the enduring lesson of Ipcar’s art, so powerfully expressed in this exhibition, and it comes with a mandate: “I really think that Dahlov’s generosity – her sharing of her creative self – demands from us something beyond admiration,” says Torres. “It invites us all to face a challenge – a challenge to face our own creative selves.”

“Dahlov Ipcar: Blue Moons and Menageries” is on view through October 6. The Bates College Museum of Art at the Olin Arts Center is at 75 Russell Street in Lewiston. For information, 207-786-6158 or www.bates.edu/museum.

Jessica Skwire Routhier is managing editor of Panorama, the journal of the Association of Historians of American Art. She lives in South Portland, Maine.