NORTH SALEM, N.Y. – From his meager beginnings charging $5-$10 for portraits on the sidewalk of Miami Beach, Daniel E. Greene, born in 1934 in Cincinnati, Ohio, rose to become one of the most celebrated representational portrait and figurative artists in the country. “Daniel E. Greene was an enormous talent who inspired generations of admirers around the world,” says Peter Trippi, editor-in-chief of Fine Art Connoisseur magazine. When discussing Mr Greene’s unwavering commitment to Realism, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s when the art world was focused on Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, biographer Maureen Bloomfield wrote, “To commit oneself to representational art, when the zeitgeist maintained the superiority of improvisation, required confidence and possibly bravado.” Daniel E. Greene, N.A. died at the age of 86 on Sunday, April 5, 2020, with his wife and two daughters by his side at his home in North Salem, N.Y. His wife, Wende, said the cause was congestive heart failure.

A resident of North Salem, Greene was considered by The Encyclopedia Britannica to be the foremost pastelist in the United States. He has more than 1,000 of his works in more than 700 personal and public collections in the United States and abroad. Highly regarded as a formidable portrait artist, he was known for painting leaders in government, banking, education, industry and the arts. Included in his long list of portrait subjects are First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Ayn Rand, astronaut Walter Schirra, William Randolph Hearst, “Wendy’s” founder Dave Thomas, Rush Limbaugh, composer Alan Menken, Carrie Fisher, Natalie Portman, Bryant Gumbel and Bob Schieffer of CBS TV, Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, New York City Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr, and Robert Beverly Hale, curator of American paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

He painted leaders of Hobart & William Smith Colleges, Tufts, Duke, Columbia, West Point, Penn State, Princeton, Rutgers, Yale, Harvard and many other top universities. He also did commissions for high profile figures in countless Fortune 100 companies, including Honeywell, Coca-Cola, Dupont, Endo Pharmaceuticals, American Express, The New York Stock Exchange and IBM. His work has been featured in collections worldwide, most notably the Smithsonian, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cincinnati Museum of Fine Arts, Columbus Museum of Art, Butler Institute of American Art and the House of Representatives, Washington, DC. Additionally, in a 1994 White House ceremony, Greene presented a pastel portrait of Eleanor Roosevelt to First Lady Hillary Clinton.

He authored two definitive books, Pastel and The Art of Pastel, which have been translated into nine languages, and produced six instructional videos that have been collected by artists worldwide. In 2017, a biography was published about his work titled Daniel E. Greene, Studios and Subways, An American Master, His Life and Art.

Greene was honored with myriad accolades over his 60-plus year career. Among the most significant are membership in the National Academy of Design in 1969, induction into the Pastel Society of America Hall of Fame in 1983 and the Oil Painters of America Hall of Fame in 1992, the 1999 Artist Fellowship Benjamin West Clinedinst medal for exceptional artistic achievement and the 2001 Portrait Society of America Medal of Honor for a distinguished body of work. Most recently, he and his wife, artist Wende Caporale, were presented with the 2019 Figurative Artists Convention’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

His paintings have been featured on the cover of numerous art publications, and articles about his work have appeared in prestigious journals throughout the US and Europe, including ARTnews Magazine, New York Magazine, The New York Observer, The New York Times, Disegnare & Dipingere (Italy) and Artistes Magazine (France).

When he was 17 years old, Greene dropped out of high school and moved to Miami Beach, hoping to get a job and save money for art school. He found that droves of artists were making a good living doing portraits of the seasonal tourists. He excitedly applied for a job as a sketch artist at a storefront gallery on the boardwalk, however, the aspiring young artist was told the bitter truth; he just wasn’t good enough. Unphased and driven by his trademark discipline and tenacity, he took a job installing car seat covers, bought a cheap set of pastels and a how-to drawing book, watched and learned from older artists, and finally earned a job sketching. By the end of the tourist season, after averaging seven portraits a day, he had saved enough money to move to New York City to begin his formal painting education. When he arrived there, he could barely make rent on his tiny $7/week windowless studio in Carnegie Hall. He would later joke, “I was so poor I couldn’t even afford windows!”

Greene worked in an art supply store by day so that he could take evening classes at the Art Students League. There he studied with Robert Brackman, the acclaimed realist painter who was a student of Robert Henri and George Bellows. When describing Brackman’s influence, Greene would say, “He served as my mentor and model of what an artist could be, and I owe him an enormous debt.” He credited Brackman with teaching him, among other things, to see color, which would become one of the hallmarks of Greene’s body of work. While studying at the League, he briefly experimented with abstraction, however he soon discovered, “I found that Abstract Expressionism wasn’t challenging enough.”

In later years, Greene would take over Brackman’s class at the League, perpetuating the Realist tradition.

In 1958, Greene was stationed on Governor’s Island in the Army’s special services’ art department. It was then that he met his first wife, Mary Ann, while she was singing in a nightclub in Greenwich Village. He introduced himself with the line, “Could I interest you in posing for a portrait?” Three months later they were married and moved into the seedy Clinton Hotel in Midtown Manhattan. Although the couple had to make do with a hot plate and cleaning dishes in the bathtub, the hotel room had skylights, which was ideal for the young artist.

Greene soon earned a reputation as a significant portrait artist and earned himself a place on the roster of Portraits, Incorporated, the premiere portrait gallery in the country. His newfound success enabled him to buy a duplex studio apartment on West 67th Street, with 20-foot-high windows and enough space for him to begin teaching private portrait painting classes. The move to 67th Street established him in a community of successful artists who worked in a variety of media, including acclaimed photographers Arnold Newman and Philippe Halsman; many of whom were also represented by Portraits Incorporated. It was there, in 1965, that Greene and Mary Ann’s daughter Erika was born. The 1960s was also significant in that Greene was elected into the National Academy of Design, an honorary association of American artists, and he was invited to join the Salmagundi Club and the National Arts Club, two of the oldest artists clubs in the country.

While enjoying his success as a portrait artist and educator, Greene was also prolifically producing his own figurative works, many of which were displayed in a Madison Avenue gallery he started with two other artists. These works were among a series of themed paintings which brought the artist renown and numerous awards.

In the late 1970s, after his second marriage ended and he relinquished his 67th Street studio, Greene traveled to Paris where he rented a small studio in the famous artist district of Montparnasse for several months where he painted and mingled with other expatriate artists. Disappointed with the contemporary art scene there and missing the vibrance of New York’s art community, he returned home and took a tiny studio near Sutton Place.

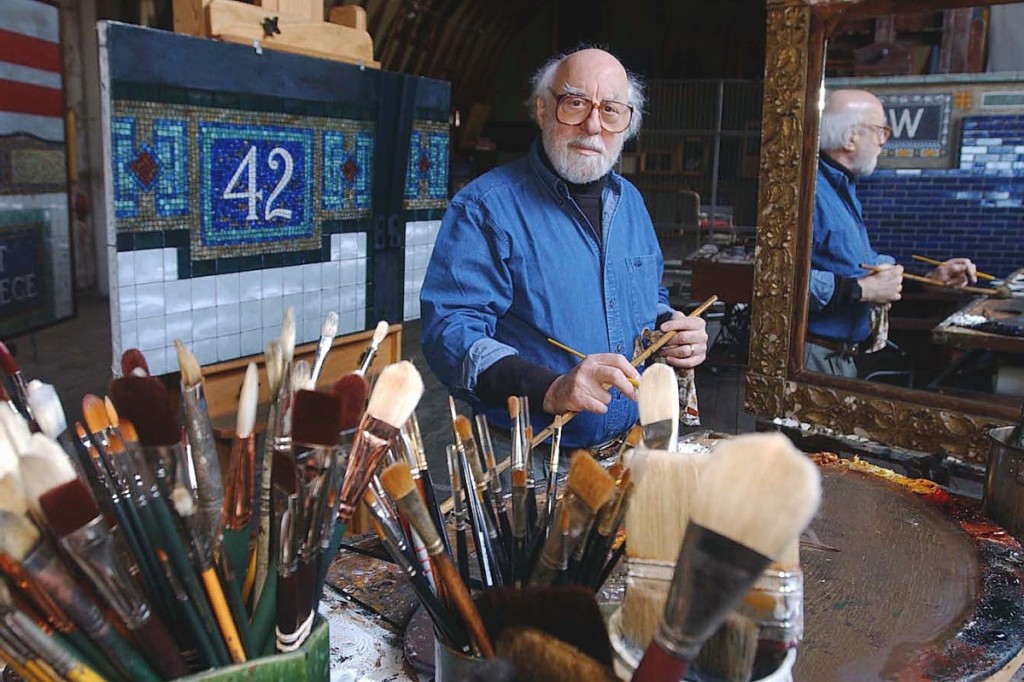

While he lived on East 52nd Street, he taught two summer workshops in Gloucester, Mass., where he soon discovered he loved being in the country. Inspired to make a big move, he looked at more than 50 properties within close proximity to Manhattan, and finally settled on one in North Salem, N.Y. The 6,000-square-foot dairy barn adjacent to a carriage house was fitted with north facing windows, which is what ultimately sealed the deal. “That’s the kind of light painters have been using for centuries,” he explained. In this expansive space, which he named “Studio Hill Farm,” he began to explore new themes: auction paintings, figure compositions, still life paintings that incorporated unexpectedly juxtaposed objects, memories of childhood amusement parks and his iconic subway series.

In 1982, he introduced a summer-long workshop in his barn that he continued to teach for the next 35 years. The first summer, he met a very talented young pastel artist, Wende Caporale, who had registered for two weeks of his class. So enthralled with Greene’s artistic talent and gift for teaching, Wende ended up staying for the entire summer, during which time their relationship blossomed and developed well beyond that of student and teacher. They were married in 1986 and several years later gave birth to their daughter, Avignon.

In the early 1990s, Greene turned his attention to the New York City subway, with its elaborate mosaic tile images. He recalled an incident in the 1950s seeing a couple sitting together in front of one of the mosaics at a subway station and thinking it would make an interesting painting. That image was filed away for years, but decades later, while honeymooning in Europe with Wende, he saw ancient mosaics in Rome and Pompeii that jarred that old memory loose. “I went back to the subway to collect information for that particular painting that I had been thinking about doing for so many years. I found, to my surprise, that there was a mass of material. The possibilities for interesting paintings and intricate mosaics was endless.”

The new millennium marked the beginning of two new series: antique auctions and carnival scenes. The inspiration for his auction series came out of a longstanding passion he and his wife Wende had for collecting antiques and attending auctions in the city. Greene described being particularly drawn to the tension and drama that is immediately present at auctions.

Greene was not just a world-renowned painter, he was a brilliant and highly revered educator. During almost six decades of teaching portrait painting, he taught more than 10,000 students at venues across the United States and Europe, most notably at the National Academy of Design and the Art Students League. Some of his students went on to paint presidents, a first lady, politicians, foreign dignitaries and other influential figures. Students from around the world flocked to his classes, often following him, like art groupies, from venue to venue. One of them described his approach to teaching as being “brutally but gently honest,” and highlighted his unique ability to articulate criticism tailored to every student, regardless of their level of experience. Dozens of his students also went on to have successful teaching careers, perpetuating his legacy and the skills they acquired under his tutelage, most notably his analytical method of drawing and his signature palette of colors.

When critics and art historians discussed his work, Greene would bristle if they used terms like hyper-realism to describe his painting style. In a recent interview he said, “I would describe it as an effort to replicate a moment in time realistically. So my style is Representational, with an emphasis that references many of the time-honored ingredients that the great painters of the past have employed… I’m trying to incorporate my version of these fundamental characteristics of painting.”

Greene is survived by his wife, Wende Caporale-Greene, daughter Erika Greene and her husband Peter Saraf, daughter Avignon Greene and her fiancée Bri Winder, and two grandchildren, Oscar Saraf and Olive Saraf.