Review by Madelia Hickman Ring, Catalog Photos Courtesy Freeman’s

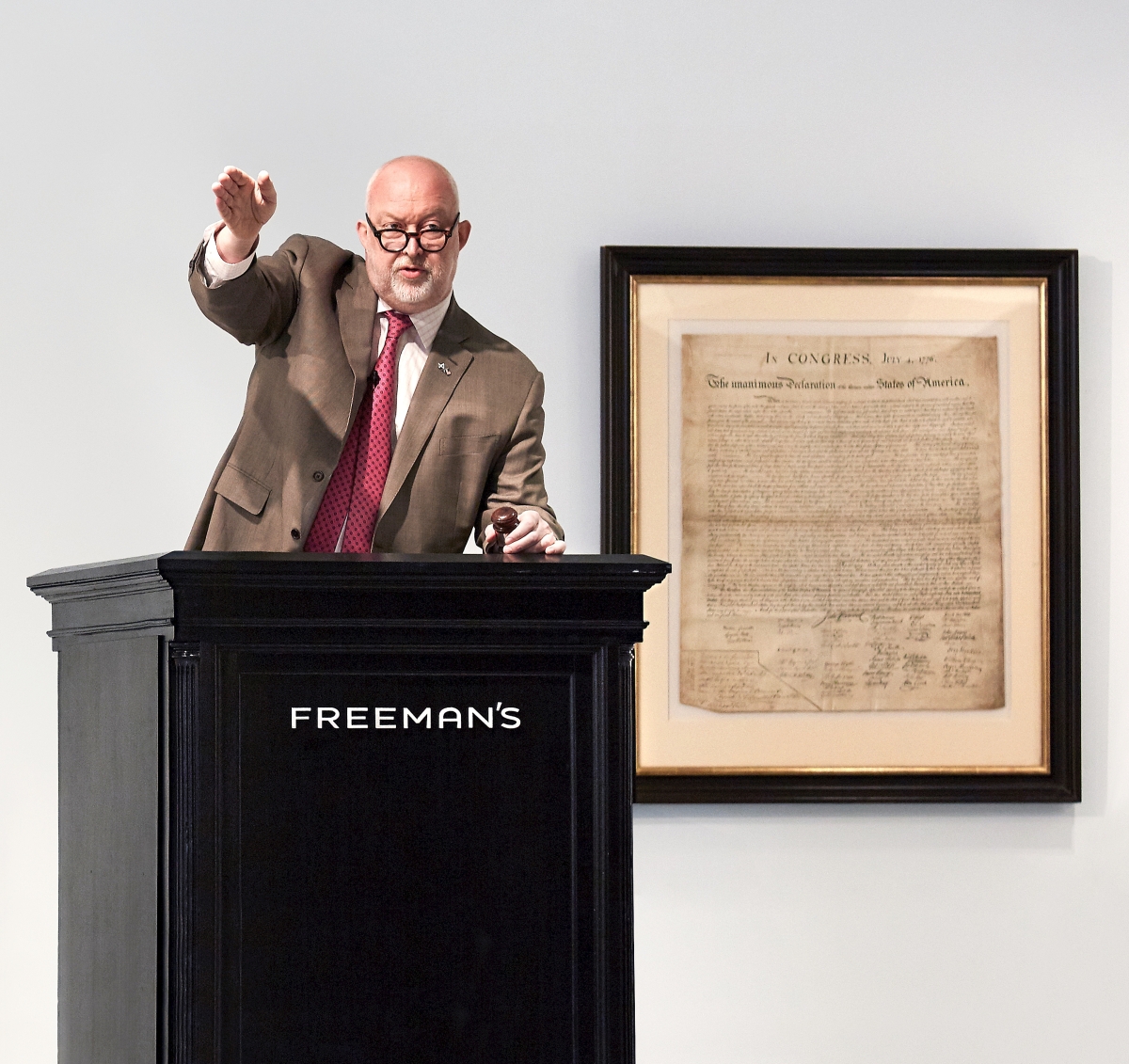

PHILADELPHIA – A single-lot sale has the potential to do very well…or very badly. Fortunately, the news from Philadelphia was glowing when Freeman’s offered one of six official copies of the Declaration of Independence given to surviving signers in 1824. After a bidding battle that quickly left absentee bidders in the dust, three phone bidders volleyed to $4.42 million, setting a new world record for a William J. Stone printing of one of the most iconic documents in the United States. The result was significant not least for the result, but because of the timing and location of the sale – 245 years almost to the day the original document was signed and mere blocks away from that historic moment.

“I couldn’t be happier for the consignors, the new owner and Freeman’s,” says Darren Winston, head of Freeman’s books and manuscripts department. “From its fairytale-like discovery through to today’s record-breaking auction, it has been both incredibly exciting and a true privilege to be involved with the sale of this significant piece of American history.”

Winston was not able to identify the buyer, though he said they had never bought at Freeman’s previously.

A screenshot of the YouTube video Freeman’s made of a dialogue between Darren Winston, left, and Lyon & Turnbull’s book specialist, Cathy Marsden, who discovered the document with a Scottish family.

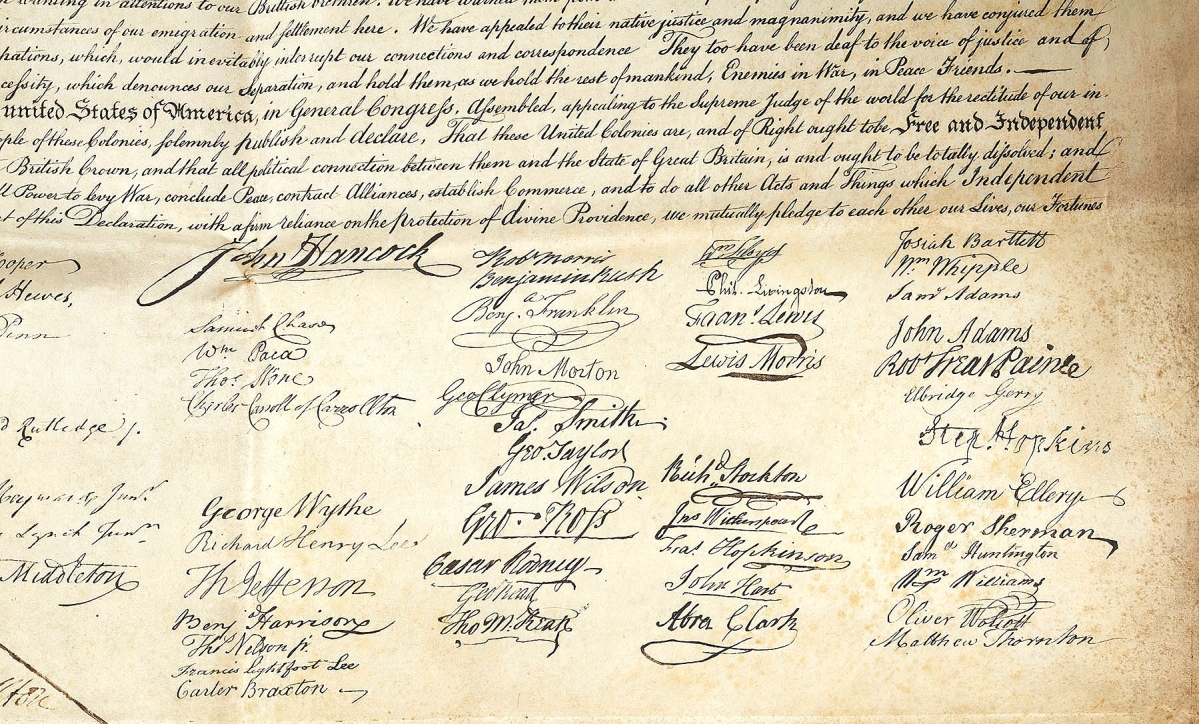

Wishing to preserve for posterity the image of the original Declaration of Independence, John Quincy Adams, then Secretary of State, obtained Congressional approval in 1820 to commission William J. Stone to engrave a plate to make exact copies of the Declaration. It was a task that took Stone nearly three years to complete. In 1824, Congress ordered Stone to print 200 copies for distribution; all are copperplate engravings on vellum inscribed “Engraved By W.I. Stone, for the Dept. of State by order/of J.Q. Adams Sect. of State, July 4th 1823”.

Of the 200 made – 201 in total including the copy Stone made for himself – the first to receive two copies each were the three surviving signers of the original document: John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and Charles Carroll of Carrollton, Md.

The document Freeman’s offered was one of Carroll’s copies.

Both of John Adams’ copies are at the Massachusetts Historical Society, each inscribed by John Quincy Adams when he was managing his father’s estate. When Jefferson died, his estate was largely disbursed and there is no record of what happened to his Stone copies. According to Freeman’s catalog essay, they are not counted among the signer’s examples known to survive.

Signatures at the bottom of the document. Carroll’s signature is four signatures below that of John Hancock.

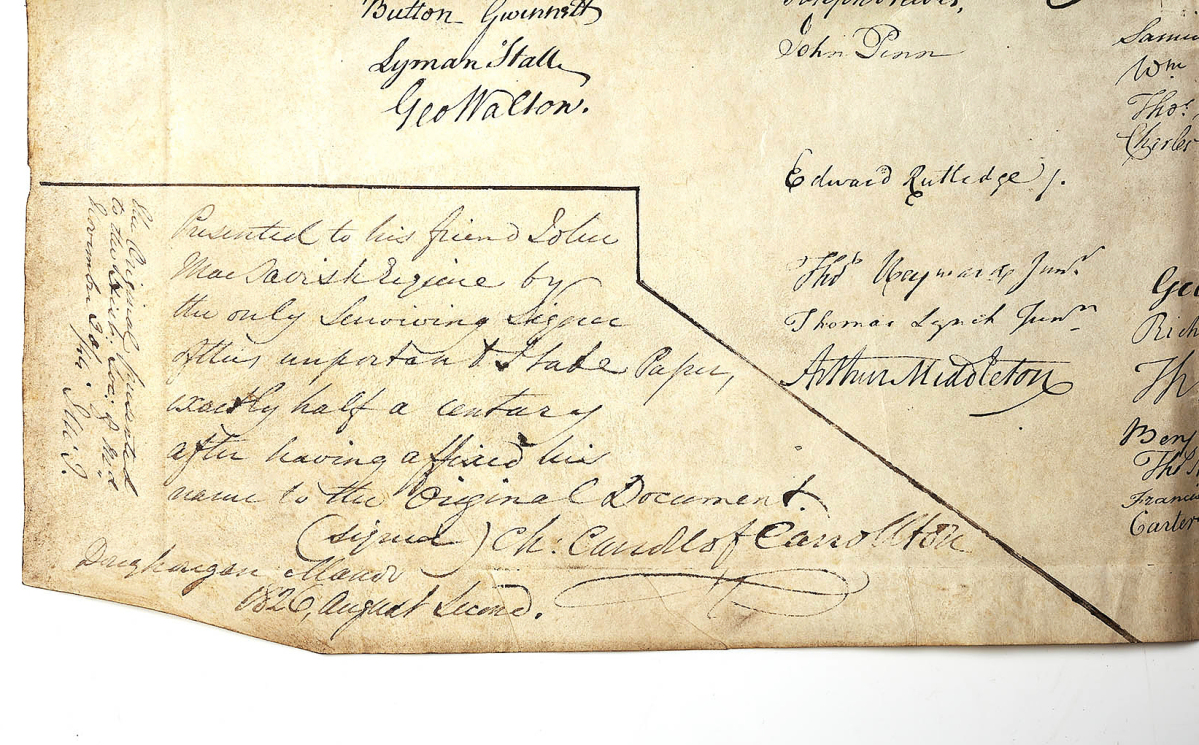

Both Adams and Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, within hours of each other. One month later, Carroll, who by then was the sole surviving original signer, inscribed and gave at least one, if not both, of his copies to John MacTavish, his grandson-in-law. MacTavish (1787-1852) was a Scottish Canadian diplomat and businessman who served as British Consul to the State of Maryland, and was also the heir to the Canadian North West Company fur trading business. He married Carroll’s granddaughter, Emily Caton (1794/5-1867), at Carroll’s estate, Doughoregan Manor, on August 15, 1815. Before Carroll died in 1832, he was cared for by Emily in her downtown Baltimore home. In 1834, after the death of executor Robert Oliver, she was appointed executrix of Carroll’s estate by the courts.

According to the inscription on the document, MacTavish gave one of those copies to the Maryland Historical Society when it was founded in 1844; the historical society, which has been renamed the Maryland Center for History and Culture, retains it in its collection to this day.

Carroll’s inscription reads, “Presented to his friend John/Mac Tavish Esquire by/the only Surviving Signer/of this important State Paper,/exactly half a century/after having affixed his/name to the Original Document./(Signed) Ch. Carroll of Carrollton/ Doughoregan Manor/1826, August Second.” The signer wrote that inscription on his other copy before giving it to MacTavish, who copied it onto this document (so Carroll’s “signature” here was penned by MacTavish), and then added: “The Original presented/to the Hist: Soc: of Md/November 30/[18]44./JMc T.”

The inscription was a critical component to identifying who had owned the document previously.

Winston said the 31¾-by-27-3/8-inch document had survived in amazing condition. “It looked like it had been folded once and never folded again. The ink is deep and bright and resonant, and it was never framed.”

The document was discovered in Scotland by Cathy Marsden of Freeman’s sister house in Edinburgh, Lyon & Turnbull. It was with a family whose collection she had been called in to appraise. Winston said neither he nor the family in Scotland had been able to determine any connection between the family and the MacTavishes.

Prior to the sale, Freeman’s created a 10-minute video of a dialogue between Winston and Marsden in which she described discovering the document, the steps she took to authenticate the document and what his reaction was to seeing it when it was first uncrated upon its return to Philadelphia.

The video, which was played to people watching the sale online prior to the lot crossing the block, is worth a watch.

Freeman’s had estimated Carroll’s “important State Paper” at $500/800,000 and Freeman’s chairman, Alasdair Nichol opened the bidding at $450,000. By $1.2 million, bidders “in the book” – auction house parlance for absentee bidders – were left behind and only two phone bidders competed for the lot. At $1.5 million, a new phone bidder joined the fray and it inched up from there, finally closing after ten minutes of play.

The inscription along the bottom corner of the document identifying it as the copy Carroll gave to John MacTavish.

Bidding for the document took place primarily online, on three websites, including Freeman’s dedicated platform, which hosted 3,153 people watching the action play out. Among the viewers was the Scottish family selling the document. Winston said that they had invited Cathy Marsden to watch the sale with them. “They are thrilled,” he said. “I spoke with them seconds after the gavel came down. The wife was very sweet. She said, ‘We’ve popped the champagne – today is a great day.'”

Copies from Stone’s edition of 200 occasionally come to market, most recently in January 2019, when Sotheby’s offered the copy given to Thomas Emory, president of the Executive Council of Maryland, for $975,000. At the time, it was the highest price recorded for a Stone copy of the Declaration of Independence.

The only other copies of the Declaration of Independence more valuable than the Stone copies are those made by John Dunlap, typeset and printed as a broadside in 1776. A Dunlap copy was offered in January 2021, when it brought $990,000; the record for a Dunlap broadside is $8.14 million, a figure established in 2000 that still stands to this day.

Seth Kaller, who assisted Freeman’s in authenticating and cataloging the document, was quoted in a postsale press release as saying, “We all know the theory that great items find their market, but often that isn’t true with so many things – business, personal, political – competing for everyone’s attention. This clearly broke through; it had the greatest depth of bidders I’ve ever seen for a seven-figure document.”

The buyer allowed the document to be loaned to the National Park Service for display on Sunday, July 4, at Philadelphia’s Second Bank of the United States.

For additional information, www.freemansauction.com.

.jpg)