“Laundress” by Edouard Vuillard, 1892, oil on board. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Nancy F. and Joseph P. Keithley Collection Gift.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

CLEVELAND, OHIO — It is difficult to think of anything more tedious than laundry: a constant, repeating, unrelenting obligation of modern life. What could possibly be interesting about it — or at least, interesting enough for a museum exhibition? Edgar Degas and the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA) are here to challenge your perceptions about this thankless task, demonstrating that laundry and laundresses were in fact objects of intense fascination in the Nineteenth Century — and that the art they inspired is no less fascinating now. “Degas and the Laundress: Women, Work and Impressionism” is at the CMA through January 14.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917), an Impressionist painter and a dedicated chronicler of modern life in Paris, demonstrated an interest in laundresses as an artistic subject early in his career — before, indeed, he or anyone else identified as an “Impressionist.” “Die Büglerin (The Ironer),” now at the Neue Pinakotek Museum in Munich, made in 1869, shows Degas synthesizing many of the ideas and techniques that would come to define his work. Beyond the feathered brushwork and the interest in interior/exterior lighting — a small opening to the outdoors is visible in the deep background as a trapezoidal shape of white pigment — it conveys an interest in movement that is also evident in his famous paintings of horses and ballerinas, says CMA curator Brittany Salsbury. “We know that he was obsessed with depicting movement and motion,” says Salsbury. “You can see how he really focuses on the placement and the movement of the woman’s arms.”

Degas was not alone in being drawn to this subject. Commercial laundries were a relatively new phenomenon in later Nineteenth Century Paris, due in part to the modernization and reconstruction of the city by Baron Haussmann under Napoleon III from the 1850s into the 1870s. As the population grew and became more economically diverse, and as standards of dress evolved throughout the class spectrum, there was ever more clothing in need of washing, drying, ironing and folding; and, at the same time fewer households that had the facilities or the servant labor to do that work. The laundries that opened to fill that need provided job opportunities for the working-class women of Paris — and the women who flocked there from the nearby rural areas — but the jobs were difficult, with long hours, hot and humid working conditions and extreme physical labor. The women were also poorly paid, Salisbury notes, which caused some of them to moonlight as sex workers. The moral perils that surrounded the Paris laundry industry were the subject of Emile Zola’s wildly popular novel, L’Assomoir, first published in 1876.

“Repasseuses” by Edgar Degas, 1884-86, oil on canvas. Paris, Musée d’Orsay, Legs du comte Isaac de Camondo. Photo ©RMN-Grand Palais / Adrien Didierjean / Art Resource, NY.

But laundresses were capturing the imagination of artists, even Zola’s novel or Degas’ paintings, and these artworks are also represented in the exhibition at the CMA. Updating for modern times the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century tropes of industrious housewives or attractive servants, Honoré Daumier pictured bent and resolute laundresses lugging sacks of clothes through the streets of Paris in the 1850s-60s. Daumier’s influence on Degas is well known — Salsbury notes that “critics compared them often, and they described him as being this inheritor of the genre that Daumier had established in looking at contemporary life” — but it is also possible to see a precedent for Degas’ laundress series in works like François Bonvin’s “Woman Ironing” (1858) and Amand Gautier’s “La Repasseuse (The Ironer)” from 1855-60, with their subdued palette, focus on motion and gesture, and clothesline strung across the top of each composition — a motif that, Salsbury observes, is common in Degas’ paintings as well.

Observe, for instance, Degas’ “Woman Ironing” from some 20 years later. Here again is the clothesline, the table, the bent back, the muscular pressure through the bare forearm to the iron, the pronounced whiteness of the garment under the iron compared to the dull dress and apron the laundress wears. A later Degas work, “Repasseuses” from the Musée d’Orsay, is even more frank about the relentless physical toll of this work: one woman presses down on her iron with both hands doubled over each other, while strands of hair dangle over her eyes; the other yawns and leans back, bracing her neck in a gesture familiar to anyone who has spent the day hunched over a computer. Notable is the wine bottle in her other hand; Salsbury notes in her catalog essay that “women were often provided a ration of alcohol as partial payment for their employment and to offset its unpleasantness.” The prevalence of alcoholism in the laundries is the subject of an essay by Gretchen Schultz, also in the catalog.

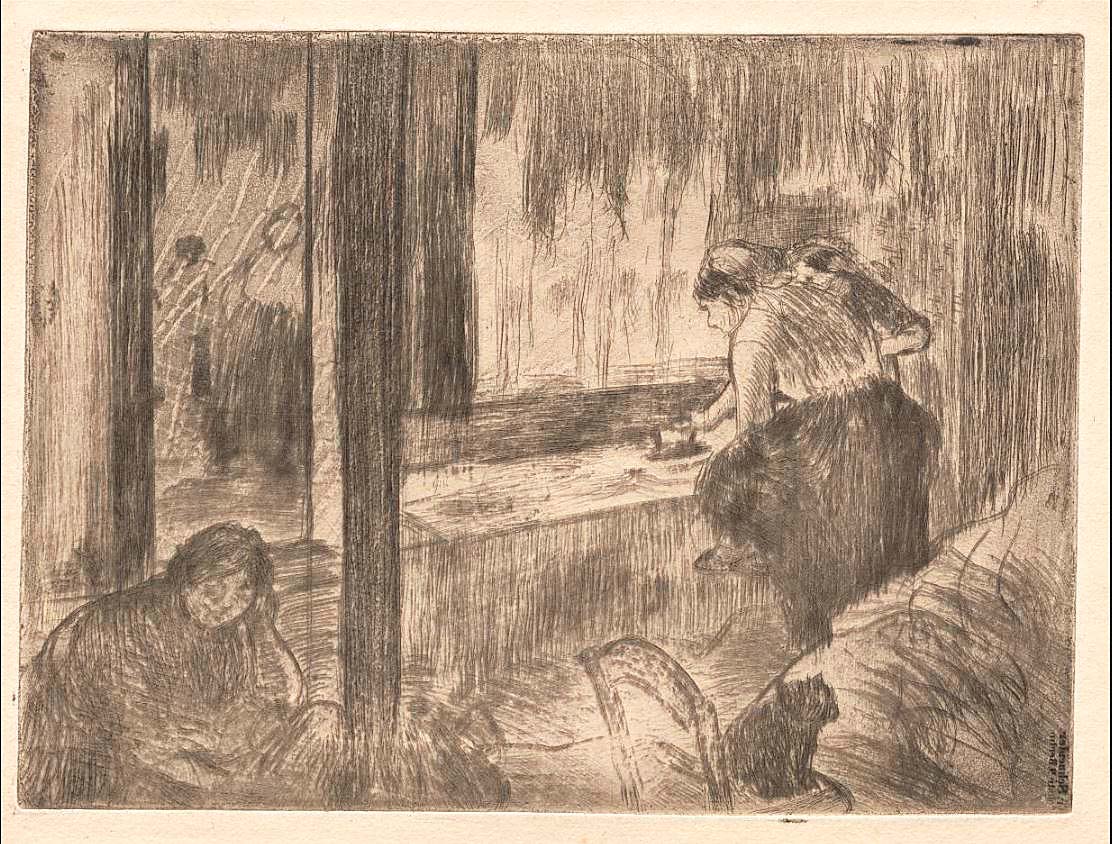

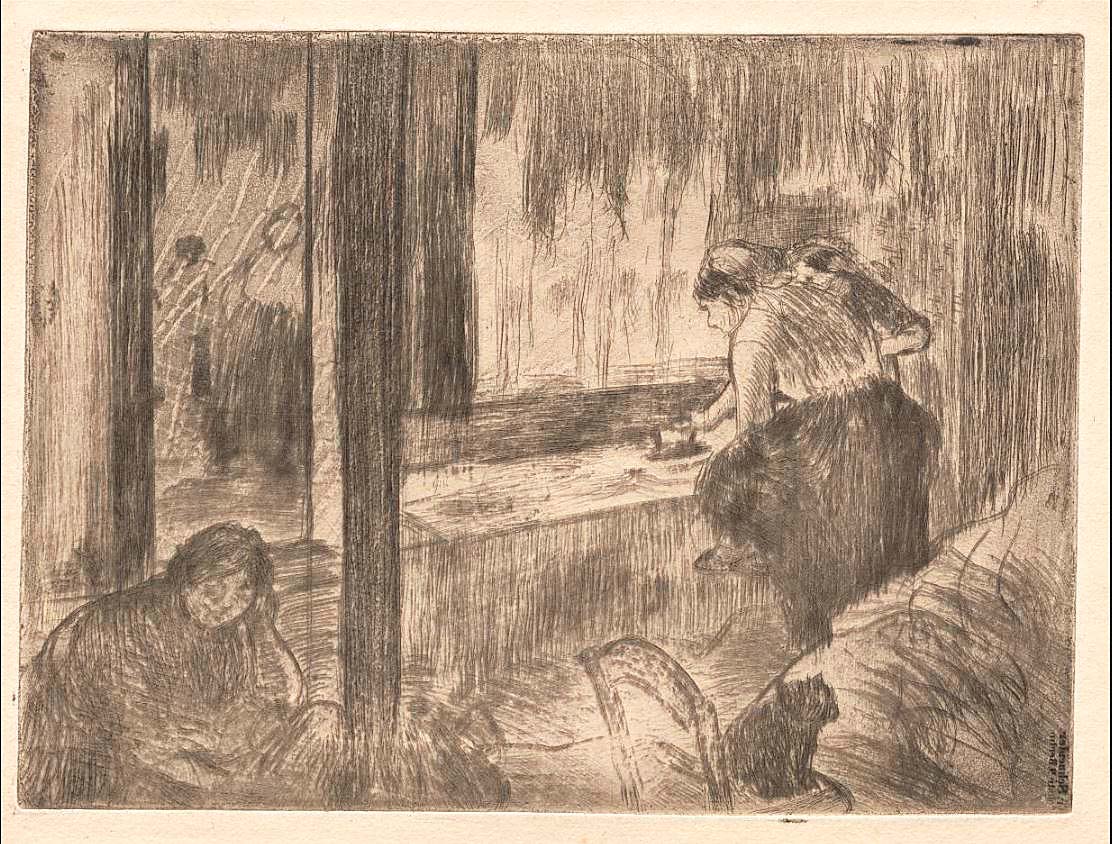

“The Laundresses” by Edgar Degas, 1879-80, etching and aquatint on beige wove paper. Norman O. Stone and Ella A. Stone Memorial Fund.

Degas was certainly interested in, and depicted, the kind of morally ambiguous realm inhabited by laundresses — beyond the bottle of wine, it is worth noting that what look to us like perfectly normal blouses would have been these women’s underclothes, their standard workday attire because of the oppressive heat in laundries — but Salsbury argues he was less exploitative about it than others. Where contemporaneous stereoviews, also represented in the exhibition, provocatively showed chemises slipping from laundresses’ breasts, this was a trick that Degas tried only once, in an early pastel now at Wellesley College — and even then he revealed no more than a shoulder. This reticence was perhaps part of the reason one critic proclaimed him a “feminist” in 1886.

“I think it’s something we can easily roll our eyes at today,” says Salsbury, clarifying that “it would be completely misguided to call him a feminist in any way.” More fruitful, perhaps, is to consider, as Salsbury does in her catalog essay, Degas’ own attitude toward work. He was famously a workaholic, and there are elements of laundry work that may have struck a chord with him in terms of his work as an artist: the physicality, the repetitiveness (particularly related to his work in printmaking), the perfectionism (especially in ironing), the aspect of being paid by completed piece. “To think that he identified with these women is, I understand, a complicated and very tricky thing to say,” Salsbury observes, adding that figuring out how to articulate Degas’ attitude toward the women who did this work was something she struggled with throughout the project. “It’s not like respect; it maybe comes close to empathy — somewhere near identification — but it’s a really tricky balance.” Further complicating things is the fact that, as far as we know, Degas was not painting actual laundresses but rather models he hired to act as laundresses — so his interaction with the working-class women that were the subjects of his art was limited.

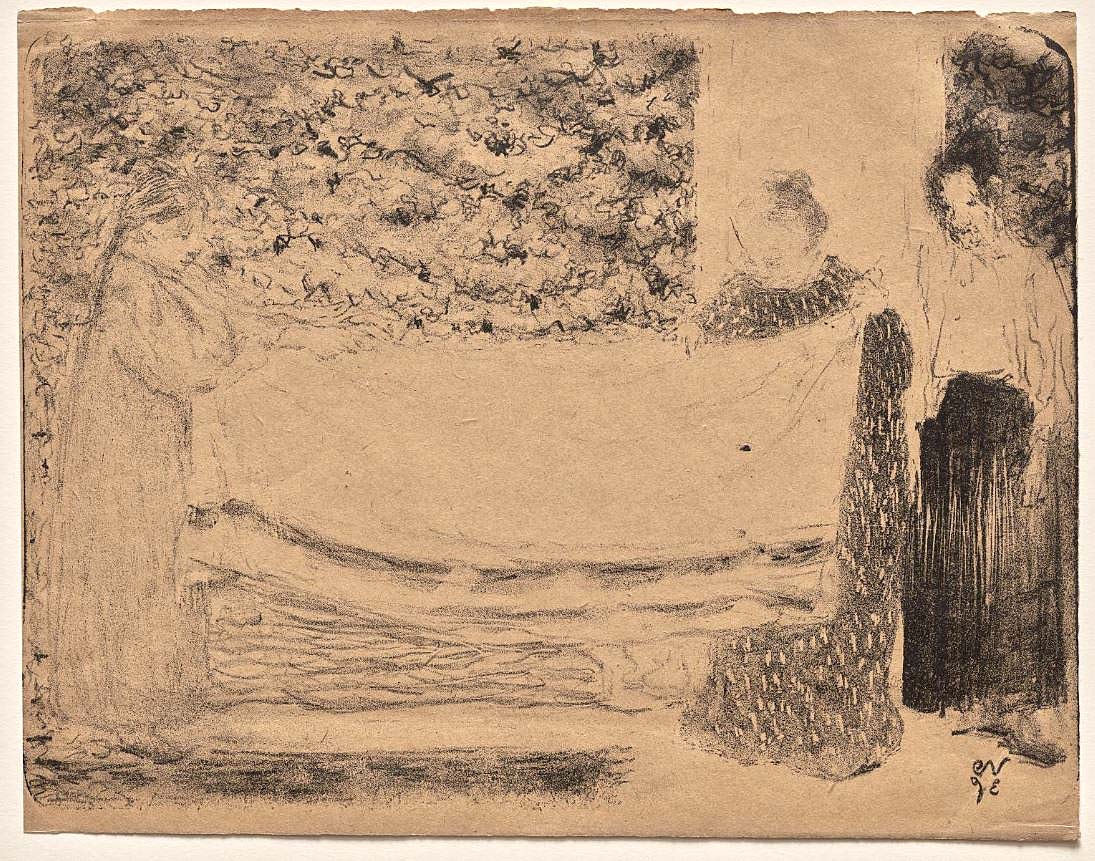

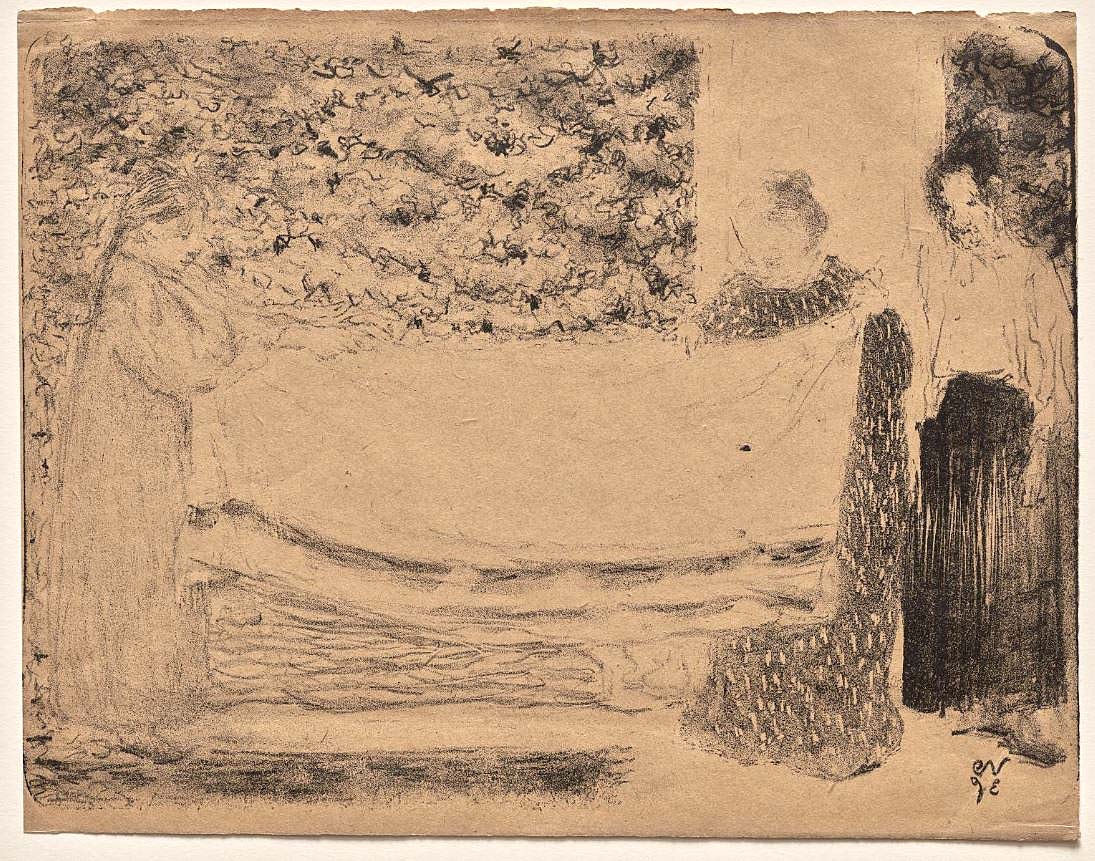

“Folding the Linen” by Edouard Vuillard, 1893, lithograph on brown wove paper. The Jane B. Tripp Charitable Lead Annuity Trust. Vuillard’s mother, widowed when the artist was a young boy, worked as a textile designer and dressmaker to support her family, and Vuillard, who lived with her until her death in 1928, was deeply influenced by his experiences of family life. He frequently used his mother and sister as models, depicting them in the midst of household tasks, such as folding laundry.

The distinctiveness of Degas’ laundress paintings, prints and pastels is evident in examining the work on a similar theme by some of his contemporaries. Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s “The Laundress” (1877-79), apart from its impressionistic brushwork, is almost a throwback to the idealized “peasant” pictures of earlier in the century. The carefully packed basket suggests that the rosy-cheeked woman is delivering laundry to a private home; despite this, she rather absurdly wears only her chemise and a skirt, and the chemise has slipped off her shoulder. The open door indicates that she may be invited within, enhancing the sexual innuendo. Edouard Vuillard’s “The Laundress,” too, seems a throwback, though in an entirely different direction. His setting also appears to be a private home — the mantel and framed artwork in the background would exclude a commercial laundry — and yet his laundress, decorously dressed in a high-necked black dress and crisp white apron, hair in a tight bun with no escaping strands, clearly belongs there and is an emblem of orderliness.

Laundresses continued to inspire artists in the generation after Degas, and like him they found ways to make the theme their own. Maximilien Luce’s “La Blanchisseuse (Philiberte Givort)” of 1905 is oddly absent of actual laundry; the loose chemise with its gaping front is the sole signifier of who this woman is meant to be. Pierre Bonnard’s lithograph “The Little Laundress” from 1896 conveys the artist’s fascination with Japanese woodblock prints, in its skewed perspective and broad swaths of color. The presence of a young girl delivering laundry on the streets of Paris might be an opportunity for social commentary, but Bonnard seems more concerned with the small, neat figure she strikes in the urban landscape. Félix Vallaton and Théophile Steinlen also depicted basket-carrying laundresses, although theirs are mature women who bustle with purpose and move through the streets with somewhat more authority. Land- and cityscapes by Berthe Morisot, Gustave Caillebotte, Camille Pissarro and many others show the laundry industry as a fully integrated and unescapable aspect of modern life in Paris and its environs.

Images of laundry and laundresses were ubiquitous in late Nineteenth Century Paris, not only in the fine arts but also in the kind of popular imagery that was consumed by people from all walks of life. Beyond the stereoviews already discussed, Salsbury says, there were caricatures, playbills, cartes de visite, sheet music covers and even postcards. For whatever reason, the laundries of Paris were remarkable to tourists, who purchased and sent to their friends postcards of laundry storefronts, with the workers lined up outside. Examples of all are included in the exhibition. “I think the thing that’s compelling about ephemera is that it gives you an idea of what most people would have actually seen, what their experience of visual culture would have been, especially for people who didn’t have other opportunities necessarily to view art,” says Salsbury.

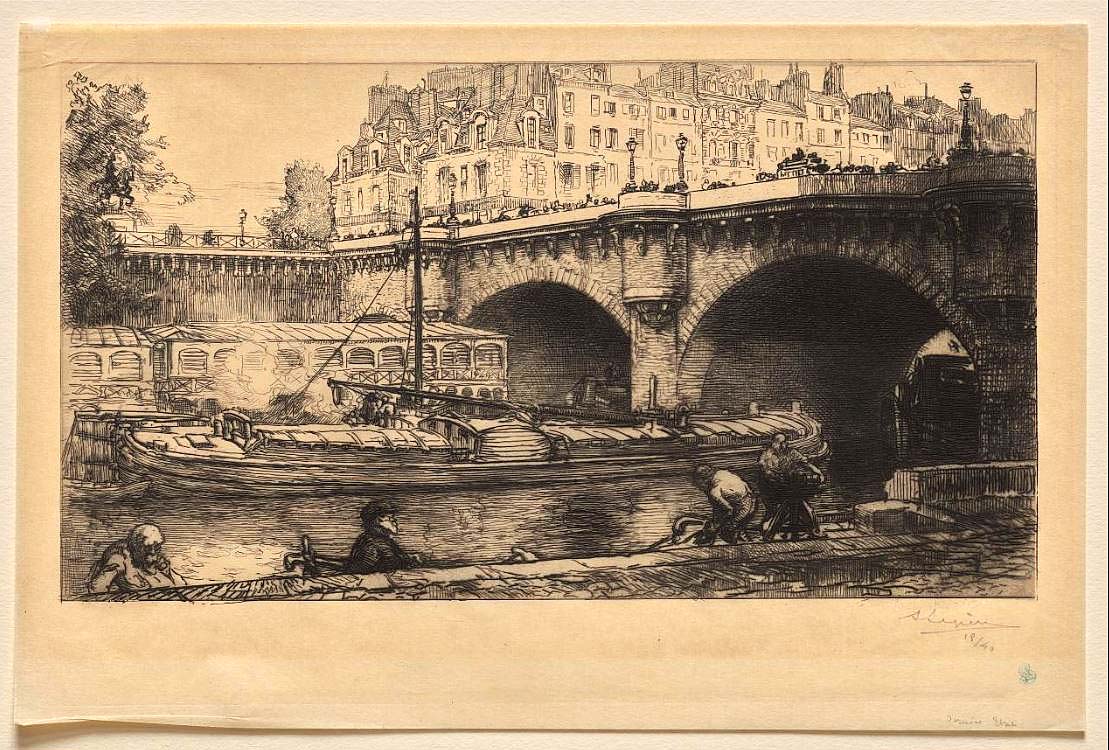

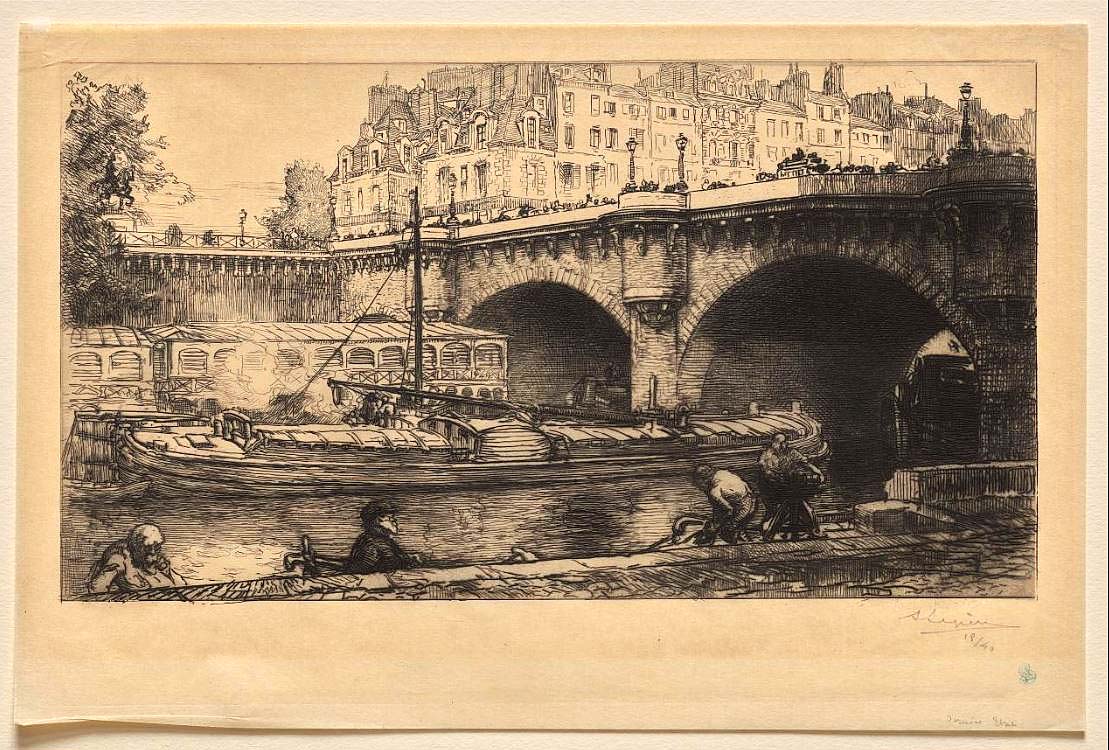

“Le Pont Neuf” by Auguste Louis Lepère (French, 1849-1918), 1901, etching. Cleveland Museum of Art; Gift of Elizabeth Carroll Shearer in memory of Robert Lundie Shearer This print depicts bateaux-lavoirs (wash boats) changed over the course of a half century, now closed so that the women working within were not visible to passersby.

The laundries of Paris were certainly an object of interest for at least one newcomer at the turn of the century, a young Spanish artist named Pablo Picasso. Experimenting with this quintessentially Parisian theme during his first sojourn in the city, Picasso created “Woman Ironing” in 1901. Although it was clearly influenced by what he was seeing in the galleries and on the streets, it has all the melancholy and figural attenuation of his so-called Blue Period, a style that was uniquely his own. A slightly later painting now at the Guggenheim (not in the CMA exhibition), shows a laundress in essentially the same pose, yet with even more exaggerated and abject physiognomy. Picasso was interested, at this time, in depicting those who lived at the margins of society, and in the laundress — with a long history of both subjugation and representation, in the work of Degas and others — he found a theme of enduring and ongoing fascination.

The Cleveland Museum of Art is at 11150 East Boulevard. For information, www.clevelandart.org or 216-421-7350.