By Erin Waters

EXETER, N.H. – Dennis “Denny” Waters died at home of liver cancer on Tuesday, May 12. He had only been diagnosed eight weeks prior. Denny was a former professional photographer, current daguerreotype dealer and longtime resident of Exeter, N.H. He was surrounded by his loving family these last weeks, his wife of 47 years, Carol, and his two children, Erin and Casey.

Dennis was an amazingly wonderful dad, an equally fantastic husband, and the best photo dealer. He was gregarious, loving and strong. You could find him in a crowded ballroom by his laughter. His family will miss him so much. They are shocked and saddened, as are so many of his near and dear friends. And they are legion. Since his death, the outreach and love from photo and antique people across the world has been humbling. And then there are family, friends, the woman who works on the Amtrak ACELA and who reached out to Erin on Instagram because Dennis was one of her favorite people “on the rails,” the people at the Water Street Bookstore where he bought a new book every week, and his friend who attends the front desk at “his” hotel in Paris.

Denny was from the village of Orwell in northeastern Ohio. He loved to joke that entering and leaving was written on the same sign to save money. An elaboration, probably, but everyone who knew him soon learned about his sense of humor and would wonder if all of his stories were true. Growing up in a small town fostered a life-long sense of community in Denny. To him, saying hello with a smile to a neighbor or a stranger walking down the street was as natural as day. He carried this friendliness to Exeter, but also on his travels to large cities like New York, Paris and London, where a smile is a bit more alien, but, when sincere, goes a long way.

Denny’s mother was a homemaker and his father owned a construction business. His maternal grandparents owned a dairy farm. He would help out on the farm growing up, riding his bike out to the family homestead – the lure of homemade ice cream at the other end of the trip. Of course, there was hard work too, like baling hay and other chores. He learned about building from his father. Both of his parents fostered a love of collecting early in him: he collected coins, baseball cards, arrowheads and comic books as a child.

Dennis graduated from Grand Valley High School in Orwell in 1970, excelling academically. He lettered in football, basketball, baseball and track. After high school, he attended the University of Missouri to study journalism, but became more of a hippie protestor than a student and soon found his way home and then to the East Coast.

He moved to Cambridge, Mass., with his cousin Chuck, who was just back from Vietnam, and would protest on the Boston Common every weekend while pretending to be a student at Harvard. He became a photographer at the Crimson, and then photographed Muhammad Ali for an article. The family has the negatives to prove it.

It was his time in Boston that led him to meet Carol, the love of his life, who was then in nursing school. He went back to Ohio for a little while to work with his dad, and they wrote letters back and forth while she worked at Mass General. It was a twist of fate that brought him to Exeter, answering an ad in the Boston Phoenix for a farm hand on a new commune because it was close to Carol in Boston. The commune had broken up by the time he got to New Hampshire, but he found work at Jones Boys Insulation and taught a photography class during summer school at Phillips Exeter Academy. He then found full-time employment as a journalist and photographer with The Exeter Newsletter. He liked to tell people that he was employed as a journalist before his class would have even graduated from college. When he set his sights on a goal, he made it happen. During his first few years in Exeter, Carol visited often and they eventually became engaged. Denny bought a house in 1972. The first renovation was a darkroom.

Carol and Denny got married in Acton, Mass., on May 12, 1973, honeymooning in Paris, Spain, and Morocco. They traveled extensively in the early years of their marriage, making their way through France, Belgium, the Netherlands, England and Colombia. Trips to Guatemala and Mexico came after they had kids.

Dennis eventually left the Newsletter and launched his career as a professional photographer. At first he did a lot of weddings and events, networking as he went, his gregarious nature serving him well.

In 1978, he and Carol welcomed their daughter Erin to the world, quickly followed in 1980 by their son Casey. As one might imagine, as children of a photographer, Erin and Casey soon were the subjects of countless photographs. Denny encouraged them from a very early age to help him in the darkroom and even took them on aerial flights, including over Hampton Beach as he leaned out of airplanes photographing summer weekend crowds. Like his father before him, he was teaching his kids the tricks of the trade.

Also in 1980, serendipity intervened and helped Denny and Carol buy a larger house just across the street with a horse barn that Denny and his dad renovated into a gorgeous photography studio. He started to do product work and portraits and was able to leave weddings behind. He was able to focus on his corporate clients and the architectural, aerial and power plant construction work that he became known for. He photographed the first prototypes of the Nike Air Sneakers here in Exeter and New Hampshire’s original copy of the Declaration of Independence that the American Independence Museum had just found rolled up in its attic.

But, in 1985, he found his life’s true passion (other than his family) when a neighbor showed Dennis his small collection of antique photographs, including some daguerreotypes. Knowing the history of photography, he had heard of them, but had never seen one. He was, as he often told people, “immediately smitten.” It was summer and he and Carol soon went on an antiquing trip to North Conway where he bought his first dag and his second and his third. He was hooked.

Although Denny remained a professional photographer until 1999, his real passion from then on was the daguerreotype. As with everything else, he put his all into it, soon meeting other people who were fascinated by these shimmering, mirror-like images that have a sharpness and depth like no other.

He quickly became an expert at photographing dags, cataloging single pieces at a time for collectors like Matthew Isenberg or entire collections like that of the Missouri Historical Society. He worked on the photography for their book, Likeness and Landscape: Thomas M. Easterly and the Art of the Daguerreotype by Dolores A. Kilgo.

Other than showering his kids with love and support in all things, the best gift he gave them was allowing them to take part in his constant exploration of Nineteenth Century photography from the get-go. If Carol had to work on a weekend, they would join him shopping at a flea market, or antiquing around New England, or at shows. Not every shop or show welcomed such small children, but Denny always sent them off on their own to find things for them. They knew how to leave deposits, tell people “daddy would be right there and to hold it please,” and, later, he trusted them to spend up to a certain amount for things. They also spent countless hours in the barn listening and looking at images with him and a revolving stream of collectors, curators, dealers and pickers who came to visit. That Erin and Casey ultimately decided to follow in his footsteps and become photography dealers made him exceedingly proud and happy.

As he continued with his collecting, meeting more people like him, he helped to build a community who loved and wanted to study daguerreotypes just as much as he did. In 1988, this led to the founding of The Daguerreian Society. Just before he died, the society awarded him its highest honor, The Fellowship Award, “for the advancement of scholarship in the field of photo history and the willingness to share that knowledge with his contemporaries and future generations of historians, scholars and collectors.” The accompanying letter noted that, “The Waters family has continually been in the forefront of keeping Daguerre’s legacy appreciated.”

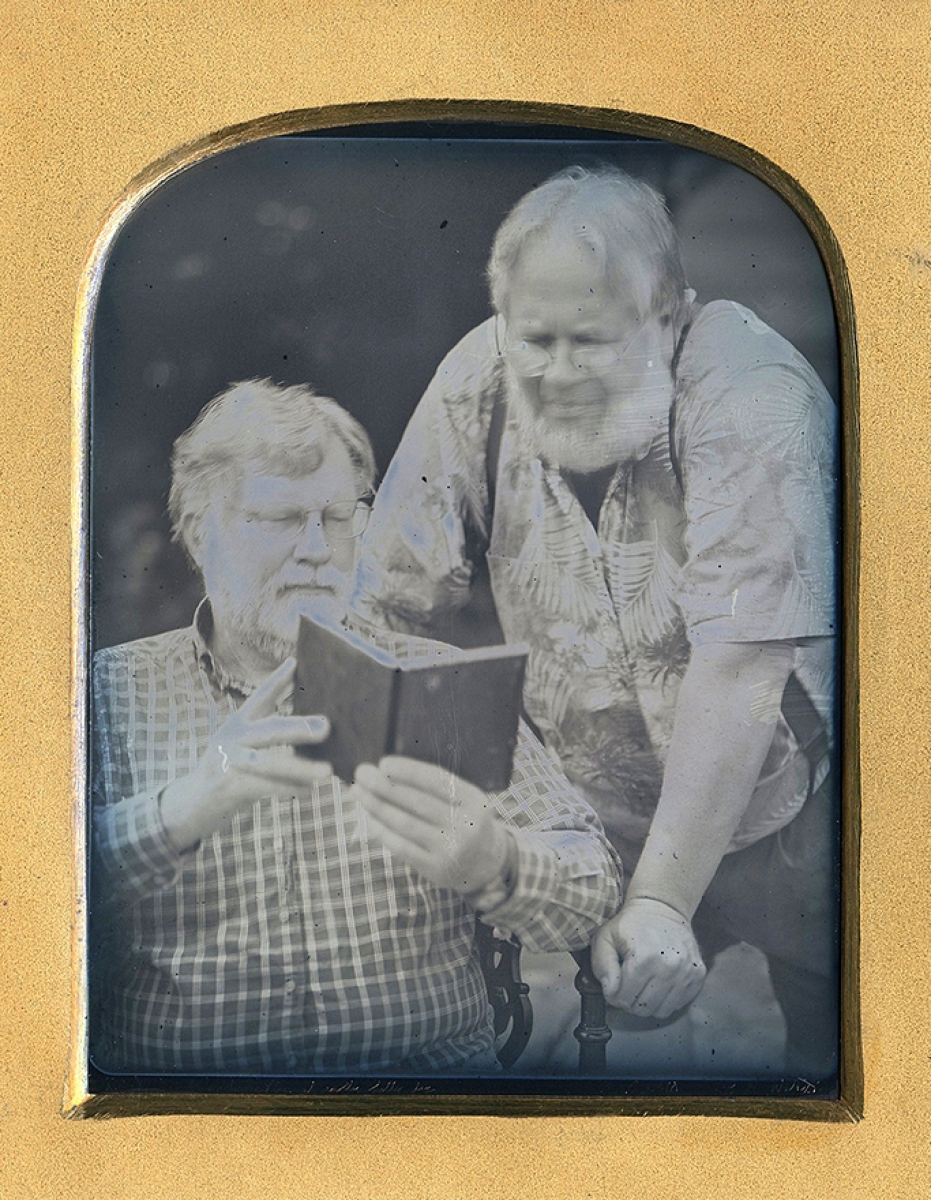

Erin and Dennis at the Gettysburg Civil War Show watching the World Cup, before switching to her phone because of WiFi issues.

In 1992, Dennis and a partner began publishing a fixed price catalog of dags for sale, The Daguerreian Forum. Buyers subscribed and received it twice a year. They loved reading Dennis’ knowledgeable descriptions that drew on his experience as a photographer and as an expert reader of people. Not only that, his best descriptions became like short stories about the dags. When people bought a dag, they often saved his description with it.

Dennis is credited with creating the market for portrait daguerreotypes and, it might be said, in Nineteenth Century vernacular photography in general. When he began trading and selling in earnest, many scoffed that he would place such high values on “simple” portraits when for so long outdoor scenes, occupationals, gold miners, etc, were the desired images. It is not that he didn’t seek out those images, too. Mining scenes paid many bills, but the portraits became his passion and specialty.

Around the turn of the century, The Forum transitioned online and became www.finedags.com. His partner having left the partnership years before, Dennis focused on making the new website the best out there for images. As with his photographs of dags, he was always known to make the very finest scans of them. People would write him all the time asking him what equipment he used.

In recent years, Denny and Carol were able to travel more and enjoyed trips to the western United States, Sweden to meet some of her family and visit clients, and to Italy. Most recently, they toured Switzerland and Northern Italy with a dear friend and client. Dennis also enjoyed trips to Europe with Erin for shows in England and Paris. They also went to Brussels recently to visit his cousin’s son and on a few trips to Switzerland to see their friend. Casey and Denny’s travels were closer to home, but just as frequent with antiquing trips around New England, local shows and meetings with dealers.

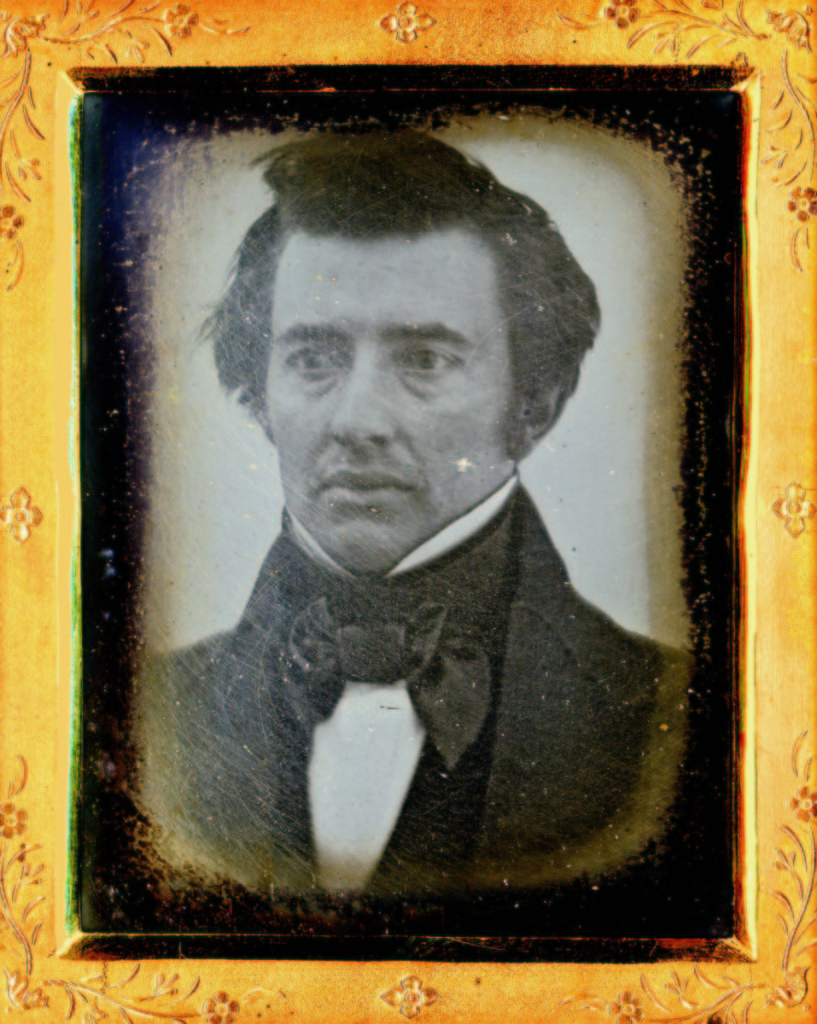

A daguerreotype in Dennis’ very early collection of dags. Albert Sands Southworth, later of the Boston firm Southworth & Hawes, probably summer 1840, by Joseph Pennell or a self portrait.

Denny, who had shopped Brimfield since the late 1980s, loved roving the fields with his children, and all three Waters were saddened when the shows were canceled this spring, just before Denny’s diagnosis. Although Erin has lived in many different places, she met up with Casey and Dennis at various shows in the United States, whether in Washington, DC; Allentown, Penn.; New York City; Emeryville, Calif.; Rochester, N.Y.; Pittsburgh, Penn.; Kansas City, Mo.; or Austin, Texas.

Four years ago, the Waters family, together with Mary L. Martin LLC, began the NYC Vintage Photo Fair. A success from the start, it had to unfortunately be postponed this year, as with so many other events in the antique world. Carol had started coming to these shows and Denny was very excited to start bringing her into the business now that she had retired from nursing. Since November, Carol has been selling on her Etsy shop, FineDagsandPhotos.

Dennis was obsessed with football, avidly following the Premier League. An ardent supporter of Liverpool, he was distressed when the pandemic postponed the season, although very understanding of the reasoning. He loved watching the World Cup as well and, during one memorable Civil War show, had Erin stream a United States match on her phone for him. It ended up being quite costly.

Denny was president of the Exeter Chamber of Commerce in the early 1980s.

Denny is survived by his wife Carol (Erickson) Waters of Exeter, N.H., and two children, Erin Waters of Lancaster, Penn., and Casey Waters of Exeter, N.H. His mother, Elizabeth (Hopes) Waters died just last month and his father Allen Waters many years ago. He is also survived by many loving aunts, uncles, cousins, nieces and nephews.

As per his wishes, there will not be a formal funeral, but when it is safe to travel, the family will have a celebration of life party in Exeter, so more about that later.

The family would like to thank The Rockingham VNA and Hospice, especially his lead nurse and fellow lover of drambuie, Silas, who helped greatly during Dennis’ last weeks and hours.

Donations in his name may be made to the Hospice Memorial Donation.

Donations may also be made in Dennis’ name to The Daguerreian Society here.

Remembering Dennis Waters

I would be hard pressed to think of a more enthusiastic, interested, thoughtful and openly sharing person, concerning the well-being of his wife, family and friends, than Dennis. He was the same with the subject of the origins of photography: enthusiastic, continuously sharing and forever interested. Each and every daguerreotype image he came into contact with he treated with interest as if it was his first time examining one. Photography and the history of daguerreotypes, next to his family, was his most important pursuit in life. Dennis was one of a kind and will be sorely missed by many.

-Victor Alford, Altamonte Springs, Fla.

I don’t know which was the first daguerreotype Dennis Waters sold to me: whether it was the Caucasian girl wearing a light-colored dress and netted gloves with her head tilted slightly in an inquisitive manner, or the young African American lady, with the long scarf wrapped around her neck and holding a scroll or a fan, with the suggestion that the portrait was possibly marking a graduation.

It wasn’t long before Dennis Waters had partnered with a mutual friend, Janos Novomeszky to start The Daguerreian Forum. And there the world got the first taste of the classic expansive descriptions brewed by Dennis; a wonderful waxing concoction of data-driven prose, embellished with flowery flights of whimsical conjecture and with the details of a condition report embedded in the body of the writing. The arrival of each catalog was an event.

Eventually Dennis would become sole proprietor of this joint venture and further down the road it would transform itself into an early pioneering daguerreian internet presence. On the website, the content would be streamlined and the pace would be quickened to biweekly. Each issue would leave bidders scrambling for their phones.

Exeter, N.H., became a daguerreian dot on the map, as the Waters clan hosted guests at their Oak Street studio. Ask Dennis how things were and he’d always remind you that “life is good.” He was dedicated to the daguerreian format and all things daguerreotype. And he was dedicated to his family: his wife, Carol, and his children, Erin and Casey.

In late March of 2020, Dennis was diagnosed with a terminal illness. His call to me came a few weeks later and it was couched from the perspective that he had some bad news for me, rather than bad news for him. Due to the gravity of the situation, we certainly commiserated but there was also a healthy dose of joking and laughing. I would see Dennis one more time on a Friday morning due to the welcoming of the Waters family.

It was in this context, at 11:53 am on the day of Dennis’ passing, I posted the following awkwardly and hastily scripted ‘news’ on the virtual pages of The Daguerreian Society Facebook page:

“The great Daguerreian dealer and collector, Dennis Waters, passed away this morning on 5/12/2020 at 11:11 am. The date was fortuitous because today is Dennis and Carol’s wedding anniversary. The Daguerreian Society decided to give Dennis the Fellowship Award. Amazingly, it arrived this morning and Casey showed it to Dennis and read the text five minutes before his passing. Carol then told him it was okay to go, and he passed. Dennis leaves two adult children, Erin and Casey, who are both in the business of antique photography as well as being collectors. Now retired as a nurse, Carol will assist in the business. The three of them were all present.”

-Greg French

I met Dennis Waters when I worked as a curator of photography at the Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Over the years, the library acquired about ten important daguerreotypes from Dennis. The one thing that set Dennis apart from other photography dealers that I worked with was his frequent, old-fashioned telephone calls. The calls always centered around daguerreotypes that he had recently acquired. His enthusiasm was infectious. I also knew I could call on him for his expertise when I had questions about the library’s own daguerreotypes.

I was surprised that after I retired, Dennis continued his phone calls. I joined him and his children at the Brimfield Antique Show and we also traveled to the Round Top, Texas, antique fair. It was at these events that I saw Dennis in action, searching the fields for new material.

My last conversation with him was about two weeks before he died. He called to tell me about a new mammoth plate daguerreotype that had come into his possession, but he wouldn’t share any details! A few days later he sent me a text with a scan of the daguerreotype portrait. Dennis found his niche in the world with photography and was always happy to share his knowledge.

I personally only bought a few photographs from him, but my favorite purchase was a sixth-plate tintype of a man with two elephants.

-Carol Johnson, curator, Eyes on Main Street

It’s hard to put a big personality like Dennis into a few words, that’s for sure! I knew him to be big, and big-hearted, in every way. I met him early on in my career at Sotheby’s, and I came to know him over two decades as both a friend and a connoisseur, in equal measure.

Dennis was one of the great “eyes” in the world of daguerreotypes and other cased images. In the world of daguerreotype connoisseurship, where so many images are anonymous (we don’t know who made them, and we don’t know who’s in them), it’s the eye of the true connoisseur that can distinguish between the great, the nearly-great, the possibly great and the merely good. Dennis was one of the those people, and I learned a lot from him.

His legacy is multifaceted: the people he tutored in how to look; the collectors and institutions who own one of the magnificent photographs he sold; his early and crucial support of the Daguerreian Society, our now-global organization devoted to daguerreotypes; and especially his two children: his daughter Erin, who inherited her father’s great eye, and his son Casey, a talented, practicing daguerreotypist.

-Denise Bethel, formerly chairman, Photographs Americas, Sotheby’s New York

He was the most unbelievable human being, big in stature and even bigger in heart, with a great booming baritone and a free laughter and a great, wicked sense of humor. His appreciation and knowledge of daguerreotypes was phenomenal and, I think, unmatched in the field. He really understood the sheer magic and artistry of this early photographic process. He was especially keen and profoundly appreciative as well as knowledgeable of the very early period in the United States, right from the beginning: from 1839 to the mid-50s. Dealing with Dennis as a collector and client was always very straightforward and easy. I loved him dearly as a purveyor of magic images, first and then later on as a very dear and close trusted friend. He is an immense loss to his family, friends and to the dag community. He will be sorely missed as he was such a unique human. In fact, he is irreplaceable. Dear Dennis, rest in peace.

-Martin Kamer, Switzerland

Daguerreotypes are one of the earliest forms of photography popular only between 1839 and the late 1850s. It was a dusty backwater of scholars with a minuscule number of collectors…until Dennis Waters came along. Dennis was a “people person,” which did him well in his earlier career as a professional photographer.

As the vast majority of daguerreotypes are of people, Dennis, as a dealer, recognized both the inherent beauty of the medium but also the mystery and intrigue of the subjects who tentatively sat for the first time to have their images immortalized on a silvered piece of copper.

In publishing his early catalogs and later online, Dennis’ descriptions of his daguerreotypes were always accurate but invariably contained his creative conjecture as to the character and personality of the person. A delight to read, like short stories, Dennis made these long ago images come alive for a whole new generation of curators and collectors through his delight and infectious enthusiasm for the medium.

It could be said, in the Brimfield Antique fields or the table top photography fairs that he constantly exhibited at, that you could hear Dennis and his exuberant laugh before you saw him! He lit up a room by his presence. He was an entrepreneur, scholar, showman, but most importantly a husband and dad. Every time I heard Dennis end a phone call to his wife or children, he ended it with, “Love Ya.”

Both the museum I worked for and later I, myself, own wonderful daguerreotypes because of Dennis. However, the greatest acquisition I ever got from Dennis was his friendship. I know many others feel the same. The field of photography has lost a true original.

-Robert Flynn Johnson, curator emeritus, Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

I met Denny in 1995 and he was enormously important in helping develop the daguerreotype holdings of the Hallmark Photographic Collection (Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art). He was a larger-than-life figure, with boundless energy and an infectious enthusiasm for images. Denny came by his knowledge the “old-fashioned way,” through the careful study of many thousands of daguerreotypes. He handled extremely important and unusual pieces, now in collections around the world. He also had a fundamental love for the basic art of the daguerreotype portrait: the technical skills of these early photographers and the human importance of the images. Denny was a good friend, always fun to be with. He played a major role in expanding the market for fine daguerreotypes, and will be greatly missed by all who knew him.

-Keith F. Davis, senior curator of Photography, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Mo.