By Karla Klein Albertson

DETROIT – Imagine an era when – every two or three years – you traded in all your living room furniture and shelled out a bundle for a brand-new look. While furniture fortunately had a bit more shelf life, during the postwar years of the Twentieth Century, families were sternly judged on the forward-looking or passe style of the family automobile.

Annual design upgrades meant you could date a car by the rear taillights. Even a casual observer could gauge what kind of person you were – or thought you were – by that shining two-tone automobile you steered around town. And there was always a dream-mobile chasing through your sleeping mind.

Just as there are stylistic periods in American furniture and painting, “Detroit Style: Car Design in the Motor City, 1950-2020” puts on view 70 years of auto innovation for a cataloged exhibition that will run through June 27. On the floor of the Detroit Institute of Arts’ (DIA) galleries are 12 landmark coupes and sedans alongside original auto design drawings and related artworks. Under the direction of Benjamin W. Colman, associate curator of American Art, automobiles take their rightful place alongside other forms of design in our history of art.

The location is logical: Detroit has long been the center of America’s automobile production. Heavy metal vehicles may seem unrelated to paintings and marble statues, but a glance at those design drawings reveal the same artistic scope and inspiration as a painter’s sketches for a church fresco. In a show opening statement, Colman said, “This exhibit is a love letter to Detroit, and a celebration of an artform pioneered in our own backyard. It is a privilege to share some of the stories of the Detroit designers who transformed the modern world with their work.” Colman, who came to the DIA in 2015, is a graduate of Yale and the Winterthur program.

Antique and The Arts Weekly had the opportunity to discuss the origins and intent of the show with the curator shortly after the November opening. The presentation required a lengthy organizational period to bring together loans from private and public sources. Colman explained, “Very little of the material in the exhibit is from the DIA’s permanent collection. Only a single object, a 1960s sculpture by John Chamberlain that has been at the museum for decades. Otherwise – the 12 cars, the 36 drawings and a small selection of paintings and sculptures – are all on loan. Many from local collections but really from all over the country.”

“The exhibit got its start in two directions at once,” Colman continued, “it follows in broad strokes on the heels of an exhibition the museum mounted in 1983, also called ‘Detroit Style’ that examined automotive form from 1925 to 1950. So, in a direct way, we’re taking up the story where that earlier exhibit left off, tracing the history of automotive design from 1950 to the present day. The other inspiration was the realization that there were incredible resources in local collections for these drawings, which are very seldom exhibited in art museums. That was something we realized when the museum was approached by a handful of designers and local collectors to make us aware of these incredible things in our own backyard, which the museum had not historically collected or exhibited.”

Two classics in a nose-to-nose muscle match-up. At left, the legendary 1967 Ford Mustang Fastback in black — at right, a menacing red 1970 Plymouth Barracuda. The sculpture between them is “Cool Wha Zee,” 1962, by John Chamberlain (1927-2011), who often constructed his works from crushed automobile steel.

Colman added, “The concept sketches and the drawings from the car design studios were never intended to survive. They were ephemeral working documents, and, in their day, they were closely guarded corporate property. Of the 35 that we have on view in the exhibition, they represent truly the smallest tip of the iceberg for what would have been made. When we speak to designers to ask about their work, many are quick to remind me that the drawings that survive are only a fraction of the hundreds they would have made in the course of creating a car at the drawing board. It’s almost an accident of history that these survived at all, we’re so fortunate that they had.”

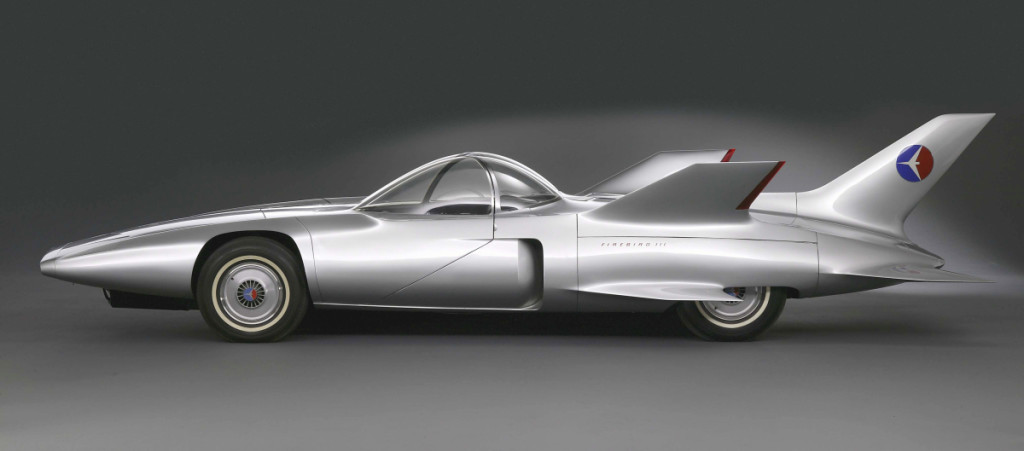

The period covered in the galleries coincides with America’s growing interest in space flight, and the 1958 Firebird on display is a perfect example of a rocket for the road. As the catalog entry explains: “General Motors’ futuristic Firebird III was designed to shock the public with visions of space-age technology brought to earth… With its streamlined body, towering fins and protruding bubbles for the cabin, this 1958 show car powerfully evoked a supersonic jet or a spaceship from a science fiction movie.”

The displays are divided between true concept cars that were never in actual production, the great muscle and sports models that appealed to the adventurous, and the vehicles that the fashion-conscious family would test drive and purchase. The Chrysler 1957 300C was part of the brand’s “Forward Look.” You might not own a rocket, but you could still drive those tailfins to work. Likewise, a prosperous entrepreneur could not acquire the General Motors Stingray Racer but might still covet their own Corvette.

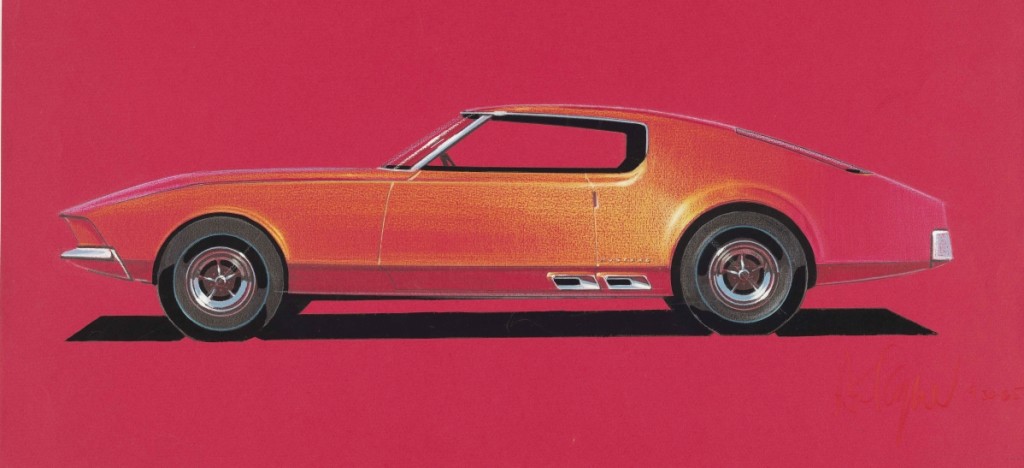

“Ford Mustang” by Howard Payne, 1965. Prismacolor and gouache on red charcoal paper. Collection of Brett Snyder.

During this era, driving around in your car morphed from a means-to-a-place into a recreational sport. No surprise that two of the most attention getting objects on the floor are a pair of quintessential muscle cars: a 1967 Ford Mustang and the high-ended 1970 Plymouth Barracuda. The curator noted, “These two great muscle cars, displayed nose-to-nose, exhibit the angles and forms of the design, the character of those cars.”

While the street driver of that era might have risked the possibility of flying or dying, you could always hear them coming. The era of consuming immense quantities of gasoline has come to an end, but these models as artifacts appear sleek and visually impressive. A great way to share the feel and sound of that horse-power rich era is to pull up the classic chase scene from Bullitt (1968) with Steve McQueen in a Mustang up against a Dodge Charger. The streets of San Francisco give a new meaning to “hitting the road.”

To plan such an extensive exhibition, Ben Colman had a vision of what he hoped viewers would take away from their visit: “The important thing I hope to achieve is the recognition and regard that we have for car designers. These are the artists who worked often in studios in the museum’s backyard but had not received the same level of wide-spread popular recognition as their peer group of architects and designers.”

An unobtainable object of desire for the public at large, this custom 1959 Corvette Stingray racer set the style for future production models.

“I’m thinking particularly of the midcentury moment in the 1950s and 1960s, when a group of product designers in Detroit created and interpreted the Midcentury Modern style that you can see on view now in almost every design museum in the world. People like Eero Saarinen, Charles and Ray Eames – they all trained and worked in Detroit at different points in their career, and they are now household names. The peer group of car designers working in the same years have never received the same level of recognition for the role they played in creating the look and field of the modern era. So, I hope people who visit the show understand the really vital processes that underscore car design and gain a fresh regard for ingenuity and skill that goes into creating these cars.”

The curator concluded, “I see myself very much as a historian in that regard, helping to remind people and document the kind of conversations that were happening in this historical period. One of the cars in the 1980s, for instance, won an industrial design award. When General Motors in the 1950s was planning the debut of some of their new cars, they photographed them alongside late model couture dresses from American and European designers. So, historically, there has been this awareness of the interplay and conversation of design media. And I hope to remind visitors to the museum just how active that conversation is.”

With a six-month run ahead, “Detroit Style” is a perfect exhibition to see in person; put it on the wish list for a back-to-normal future. Fortunately, generous funding allowed the show to offer a brilliant illustrated catalog – featuring all the cars, all the drawings and interviews with major auto designers – for only $40 at diashop.org. Add a new angle on Twentieth Century design to the reference shelf.

The Detroit Institute of Arts Museum is at 5200 Woodward Ave. For more information, www.dia.org or 313-833-7900.